Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6703

Revised: August 14, 2013

Accepted: August 17, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 138 Days and 6.9 Hours

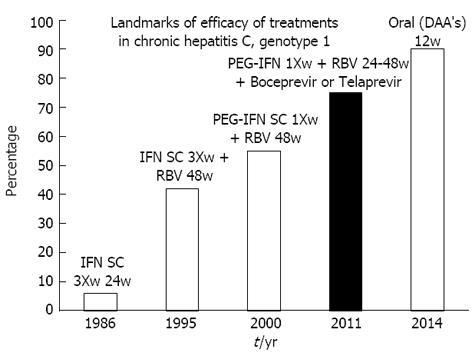

The infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the most important global chronic viral infections worldwide. It is estimated to affect around 3% of the world population, about 170-200 million people. Great part of the infections are asymptomatic, the patient can be a chronic carrier for decades without knowing it. The most severe consequences of the chronic infection are liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which appears in 20%-40% of the patients, leading to hepatic failure and death. The HCV was discovered 25 years ago in 1989, is a RNA virus and classified by the World Health Organization as an oncogenic one. Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most important cancers, the fifth worldwide in terms of mortality. It has been increasing in the Ocidental world, mainly due to chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis C is not only a liver disease and a cause of cirrhosis, but also a mental, psychological, familiar, and social disease. The stigma that the infected person sometimes carries is tremendous having multiple consequences. The main cause is lack of adequate information, even in the health professionals setting. But, besides the “drama” of being infected, health professionals, family, society and the infected patients, must be aware of the chance of real cure and total and definitive elimination of the virus. The treatment for hepatitis C has begun in the last 80´s with a percentage of cure of 6%. Step by step the efficacy of the therapy for hepatitis C is rapidly increasing and nowadays with the very new medications, the so called Direct Antiviral Agents-DAAs of new generation, is around 80%-90%.

Core tip: Around 3% of the world population, about 170-200 million people are infected with hepatitis C virus. The chronic consequences of the infection are liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which appears in 20%-40% of the patients. Hepatitis C is not only a liver disease but also a mental, psychological, familiar, and social disease. The stigma that the infected person sometimes carries is tremendous. But, besides the “drama” of being infected, health professionals, family, society and infected patients, must be aware of the chance of real cure and definitive elimination of the virus. Step by step, the efficacy of the therapy for hepatitis C is rapidly increasing and with the new medications, the Direct Antiviral Agents-DAAs, is around 80%-90%.

- Citation: Marinho RT, Barreira DP. Hepatitis C, stigma and cure. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(40): 6703-6709

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i40/6703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6703

Hepatitis C is one of the most important global chronic infection worldwide: it is estimated to affect 170-200 million people, while chronic hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection affects respectively 350 million and 34 million. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C. Hepatitis B is easily preventable by vaccination. Another characteristic of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the high risk of evolution to chronicity, more than 50% which can be around 80% in same series[1]. Another characteristic is the absence of symptoms for decades before the phase of decompensation of liver cirrhosis and the appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma.

The most severe chronic consequences of the infection are liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, leading to hepatic failure and death, which can appear in 20%-40% of the patients[2].

In effect, cirrhosis is the end-stage of every chronic liver disease. Its natural history is characterized by an asymptomatic phase, called “compensated” followed after several years or decades by a “decompensated” phase. The patient, in the decompensated phase has a median of survival of 2 years[3].

This phase can be characterized by a rapid clinical evolution with all the complications of a cirrhotic liver with portal hypertension: ascites, sepsis (the majority from spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), varices bleeding, jaundice, mental alterations (encephalopathy), renal failure (hepatorenal syndrome), caquexia[4,5].

Liver cirrhosis is one of the most oncogenic situations in medical terms. The development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a real fact, occurring in 1%-4% each year and is becoming in some centers the most frequent complication of HCV cirrhosis[6].

The quality of life in the decompensated phase can be very poor with frequent hospitalizations and readmissions[7]. At this stage only liver transplantation is really effective for median or long term survival. But if the virus is still active, the reinfection is almost universal[8]. But, besides the “drama” of being infected, health professionals, family, society and infected patients, must be aware of the chance of real cure and total and definitive elimination of the virus[9].

The HCV was discovered 25 years ago in 1989, is a RNA virus and classified by the World Health Organization as an oncogenic one[10]. The discover of the virus has open the way to a diagnosis test (anti-HCV) and several studies of molecular biology, virology and pharmacology[11]. The treatments for hepatitis C has begun in the last 80´s with a percentage of cure of 6%[12]. Step by step the efficacy of the therapy for hepatitis C is rapidly increasing and nowadays with the very new medications, the oral Direct Antiviral Agents-DAAs, is around 80%-90%[13].

The therapy of hepatitis C is an example of the capacity of modern medicine to translate the basic research to the clinical setting (Figure 1). Several types of medications have been used in to treat hepatitis C throughout these 25 years of success: first, human interferon (INF, three times weekly, 6% of efficacy), in 1995 Ribavirin has appeared to be used in combination with INF (34%-42% of efficacy), in 2001 Pegylated INF once weekly with ribavirin (45% of cure for genotype 1 and 70%-80% for genotype 3)[14]. In 2011 another step with the combination of Peginterferon and Ribavirin with two Protease inhibitors, region 3/4 (Boceprevir[15] and Telaprevir[16]), the triple therapy, leading to cure in 70%-80% of cases.

Several clinical trials are in rapid development worldwide with the new DAA´s (Direct Acting Antiviral Agents) interacting with several of vital components of the virus (NS 3/4, NS5A, NS5B Polymerase, etc.). In effect a new generation medications is rapidly approaching, like Sofosbuvir[13], Daclastavir, Asunaprevir[17], ABT-450[18], Faldaprevir, Simeprevir, Deleobuvir, some of them only using oral agents, for a period of 12 wk, with a few negligible side effects, having a chance of viral eradication of 80%-90%.

In fact, in a quarter of a century, the percentage of cure has increased from 6% to 90% of cure. From three injections a week during 48 wk to some pills a day during 12 wk! Another important development that has positively affected the quality of life of patients, allowing access to treatment and possible cure is the Transitory Elastography (Fibroscan®). Is an ultrasonographic device with very good acuity in the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, mainly when there is liver cirrhosis. The number of liver biopsies has decreased[19] in some centers around 90%.

The efficacy of the therapy is assessed by on important finding, i.e., the viral load: RNA HCV (by a sensitive test) must be negative 24 wk after stopping therapy. If this happens, more than 99% of patients will never be positive again.

It is the only global chronic viral infection that is possible to cure. The other ones are hepatitis B and HIV infecting respectively 350 and 34 million people worldwide but with no chance of cure in chronic cases.

In the beginning of this story of success, the medical community was afraid of the word cure. But now it is well known this word can be used with property but with some restrictions. In effect is a virological cure for life. It is proved that virus is not detected on liver cells or mononuclear blood cells. Nor there is an occult disease as is the case for chronic hepatitis B (HBV DNA negative or with low levels, having HBsAg negative and a risk of relapse in case of immunosuppression).

Albeit is a definitive one, we must be cautious in patients having liver cirrhosis, because the chance of development of hepatocellular carcinoma is strongly reduced, but still remains. It is one of the reasons to treat patients with mild or moderate fibrosis, in order to reduce the chance, while in a stage of a less severe disease, of evolution to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver cirrhosis, per se, is a disease having a risk of 1%-4% per year of evolution to hepatocellular carcinoma.

The benefits of cure are tremendous. Hepatitis C should be considered a global disease. As for the definition of Health of World Health Organization, (“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”) chronic hepatitis C is a physical, mental and social disease, affecting globally the individual, the couple, the family, and the society as a whole.

There are some myths about hepatitis C: “almost always lethal, more severe than acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), very contagious disease, not curable, the adverse events of therapy are huge and very severe, etc.” But the benefits of cure, in global terms considering the physical, mental and social aspects are several (Table 1).

| Benefits of cure of hepatitis |

| 1 Negative HCV RNA (viral load) for life, in more than 99% of cases |

| 2 Negative HCV RNA in the liver |

| 3 HCV RNA negativation in PBMC |

| 4 No detection of the genotype |

| 5 Sometimes, a few year later, the anti-HCV test can became negative, the so called “seroreversion” |

| 6 Normalization of aminotransferases (AST, ALT) and GGT |

| 7 Changing of ultrasound findings (contours can became regular, reduce of diameter of portal vein in case of portal hypertension) |

| 8 Disappearance of the lymphnodes near the liver (helium) |

| 9 Decrease of the values for Elastography (Fibroscan®) |

| 10 Reducing the risk of progression to cirrhosis |

| 11 Reversion of cirrhosis in some cases |

| 12 Disappearance of oesophageal varices |

| 13 Reducing the risk of progression to liver cancer |

| 14 Reduced risk of decompensated liver disease (ascites, jaundice, rupture of oesophageal varices, encephalopathy) |

| 15 Reducing to zero the risk of recurrence after liver transplantation (if necessary) |

| 16 Improved quality of life (asthenia, fatigue, general well-being) |

| 17 Reducing of the psychological impact (anxiety/depression) |

| 18 Disappearance of the risk of sexual transmission |

| 19 Disappearance of the risk of perinatal transmission |

| 20 Decrease in the insurance premium |

| 21 Cure of associated conditions (porphyria cutanea tarda, polyneuropathy, urticaria, cryoglobulinemia, splenic lymphoma) |

| 22 Reducing personal, family and social stigma |

| 23 The treatment is proved cost-effective |

| 24 Benefit to public health |

| 25 Reduced risk of death from liver disease |

| 26 Neurocognitive improvement |

| 27 Cure of hepatitis C |

Besides the natural history of this disease, the personal impacts of a diagnosis of hepatitis C infection and its treatment strongly affect the patients’ quality of life[20-22]. Mental health problems frequently occur in chronic infection with HCV and during the antiviral treatment. These individuals frequently present neuropsychiatric symptoms like fatigue, anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders[23,24].

Regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms, one can identify two distinctive patterns in its relation with HCV infection. On one hand, individuals with chronic hepatitis C have higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, including depression[25]. On the other hand, individuals with psychiatric records present higher HCV infection rates than the average population[26].

A combined therapeutics using Pegylated IFN is commonly used in these patients and proves to be a fundamental and consensual intervention for a favourable change in the natural history of the disease[27,28].

However, this treatment is associated with a high number of adverse reactions like: irritability, insomnia, fatigue and loss of appetite. Apart from these, neuropsychiatric symptoms (especially depression, and sometimes with suicidal ideation) are among the most common secondary effects in therapeutics with IFN, being one of the main causes why patients interrupt their treatment[24,29,30]. It is noteworthy that, up to a certain extent, psychopathologic symptoms (depression, cognitive disorders) may be associated to HCV infection, even without an INF treatment, and may be related to direct HCV neurotoxicity[29-32].

A large number of patients undergoing treatment for VHC infection should be referred for psychiatric evaluation and, if necessary, should received treatment for depression and other neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Recognition of depression and other neuropsychiatric symptoms is important, and could improve adherence to VHC treatment. This symptomatology negatively affects the individual’s perceived quality of life, its general functioning, work capacities, less participation in life and medical care, increase mobility and mortality, decrease overall well-being and quality of life[27,33]. Furthermore, therapeutic used in HCV treatment is associated to impairment in all of these dimensions[34].

Thus, considering the impact in patients’ mental health, before and during the treatment, an interdisciplinary approach should be followed and encouraged when dealing with HCV infected patients[24].

Diagnosis with hepatitis C was reported to have profound impacts on social functioning. Perceived stigma associated with HCV infection leads to high levels of anxiety and exaggerated fear of transmission, and it can be a major cause of social isolation and reduced intimacy in relationships[35].

Epidemiological studies suggest that more than 90% of transmission in developed countries takes place through the sharing of non-sterilized needles and syringes in the intravenous drug-using population[36].

Because the vast majority of people with hepatitis C have a history of intravenous drug use, they are frequently blamed for acquiring the disease, and viewed as irresponsible, accountable and “unworthy”[37]. Furthermore, as a blood-borne disease, hepatitis C is strongly associated with HIV. This association exists due to the fact that intravenous drug abuse is a significant risk factor for contracting both diseases and this can be a stigmatizing factor for this patients[38]

Stigma can be defined as attitudes expressed by a dominant group, which views a collection of others as socially unacceptable. The notion of stigma denoting shameful relations and deviations from what is considered “normal” has a long history within infections disease, in particular HIV[39], and more recently in hepatitis C infection.

These norms, behaviours and beliefs surrounding hepatitis C infection can lead to alienation from family and friends, as well as to discrimination (perceived or real) in health services and workplaces[40].

Stigma can affect self-esteem and quality of life. It can also impede the success of diagnosis and treatment, leading to continuing risk of disease transmission. It is a social phenomenon that influences the course of illness and marginalizes patients[41].

Since stigmatization affects not only the individual but also the whole course of the disease, health care workers are not immune to stereotypes and judgements that might influence the course of the treatment of HCV patients. Changing this behaviour will help prevent patients’ isolation, withdrawal of treatment and it will increase the search for medical help[42].

Hepatitis C should have a global approach in its treatment. It requires broad-based educational efforts in order to increase the understanding of this disease, still connected to several pejorative stereotypes[42]. These efforts should include patients and their family, health care providers and the society as a whole. Further knowledge of hepatitis C stigma is central to assisting patients in self-managing their illness, and it is important to reduce the disease burden.

The goal of therapy is to eradicate HCV infection. The endpoint of therapy is sustained virological response (SVR). Once obtained, SVR usually equates to cure of infection in more than 99% of patients[43].

If the test for assessing viral load is negative 24 wk after finishing therapy, we can talk of “cure”. With the new treatments, the oral DAAs, the assessment of sustained viral response can be shortened to 12 wk after ending the treatment. HCV RNA detection and quantification should be made by a sensitive assay (lower limit of detection of 50 IU/mL or less), ideally a real-time PCR assay. If the patient has already cirrhosis, the risk of develop hepatocellular carcinoma still persist for some years and deserves an abdominal ultrasound every six mouths.

When the SVR is obtained the global benefit is as it follows: if there is no another reason for AST, ALT or GGT elevation, namely alcohol consumption or obesity, they became persistently normal.

At virological level, the HCV RNA is no longer detected in the liver[44] or even in the Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) by sensitive tests[45]. The genotype becomes and remains negative, because there is no virus for detection.

One of the things that can cause some confusion is the fact that the anti-HCV (a marker of past infection) generally remains positive. The index can decrease slowly and the anti-HCV can became negative, several years after, as it happens in the context of acute hepatitis C[46].

On the Hepatic Elastography (Fibroscan®) the values generally decrease along some months[47]. At the abdominal ultrasound the findings can change: the liver contours can become regular, the diameter of portal vein reduces in case of presence of portal hypertension. The disappearance of the lymph nodes in the hepatic hilum can be a finding[48]. There are some studies showing thatdimensions of these lymph nodes are related with the levels of viral replication[49].

Regarding liver disease the risk of progression to cirrhosis decreases. In some cases it occurs a reversion of cirrhosis[50]. In fact this is no longer an irreversible situation as was thought some years ago; the disappearance of oesophageal varices is also fact[51]. On the other side, there is a decrease of risk of evolution for more severe stages of liver disease like the progression hepatocellular carcinoma[52] and risk of the decompensated liver disease (ascites, jaundice, rupture of oesophageal varices, encephalopathy, jaundice, etc.)[53].

In the case that a liver transplantation would be necessary the risk of reactivation is no longer present. More than 95% of cases of patients transplanted for cirrhosis associated with HCV will have again HCV RNA positive and 50% will develop severe forms of liver disease a few years after transplant[54]. Because of that, to treat patients with cirrhosis or intense fibrosis must be done as soon as possible.

There is an improvement of quality of life[55] (asthenia, fatigue, general well-being, etc.) assessed by adequate tests and more important on the mental level there is a reduction of the psychological impact (anxiety and/or depression).

In strong relation to cure, the risk of sexual[56] and perinatal transmission[57] disappear. These are very important advantages of SVR in the treatment of hepatitis C. We must not forget, that hepatitis C, besides a liver disease is also an infectious and transmissible disease. We can consider the cure as “belonging” to the patient himself but also to his family, his couple, etc. Is also a familiar disease. There are some patients who don´t tell the family or to the couple afraid of the consequences of the bad new. If patients insist with Insurance Companies they must decrease the insurance premium because there is less risk of clinical evolution.

There are reports of the control and even disappearance of some associated conditions like porphyria cutanea tarda[58], polyneuropathy[59], urticaria[60], cryoglobulinemia[61], splenic lymphoma[62,63].

Depending on the countries and the burden of the infection, the treatment was proved to be cost-effective[64]. Reducingof personal, psychological, family and social stigma is a huge benefit for all. Stigma is a fact that must be considered in the setting of HCV therapy and also when considering the real burden of the disease.

Considering the global approach we can consider that to cure HCV chronic infection is a real benefit to public health mainly by reducing the risk of complications and dying because of liver disease. Having access to the most modern therapies, the disease is almost a curable disease and the efficacy of treatment markedly increases the survival of patients infected. Chronic hepatitis C is a silent epidemic, a global disease with a strong stigma, but with high chance of definitive cure[65].

P- Reviewers Boin I, Tang W S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Loomba R, Rivera MM, McBurney R, Park Y, Haynes-Williams V, Rehermann B, Alter HJ, Herrine SK, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH. The natural history of acute hepatitis C: clinical presentation, laboratory findings and treatment outcomes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:559-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sangiovanni A, Prati GM, Fasani P, Ronchi G, Romeo R, Manini M, Del Ninno E, Morabito A, Colombo M. The natural history of compensated cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus: A 17-year cohort study of 214 patients. Hepatology. 2006;43:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1892] [Cited by in RCA: 2134] [Article Influence: 112.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Planas R, Ballesté B, Alvarez MA, Rivera M, Montoliu S, Galeras JA, Santos J, Coll S, Morillas RM, Solà R. Natural history of decompensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. A study of 200 patients. J Hepatol. 2004;40:823-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Benvegnù L, Gios M, Boccato S, Alberti A. Natural history of compensated viral cirrhosis: a prospective study on the incidence and hierarchy of major complications. Gut. 2004;53:744-749. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bolondi L, Sofia S, Siringo S, Gaiani S, Casali A, Zironi G, Piscaglia F, Gramantieri L, Zanetti M, Sherman M. Surveillance programme of cirrhotic patients for early diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost effectiveness analysis. Gut. 2001;48:251-259. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Talwalkar JA. Determining the extent of quality health care for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;42:492-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Roche B, Samuel D. Hepatitis C virus treatment pre- and post-liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2012;32 Suppl 1:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Morisco F, Granata R, Stroffolini T, Guarino M, Donnarumma L, Gaeta L, Loperto I, Gentile I, Auriemma F, Caporaso N. Sustained virological response: a milestone in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2793-2798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359-362. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, Gitnick GL, Redeker AG, Purcell RH, Miyamura T, Dienstag JL, Alter MJ, Stevens CE. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science. 1989;244:362-364. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hoofnagle JH, Mullen KD, Jones DB, Rustgi V, Di Bisceglie A, Peters M, Waggoner JG, Park Y, Jones EA. Treatment of chronic non-A,non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1575-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, Schultz M, Davis MN, Kayali Z, Reddy KR. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1322] [Cited by in RCA: 1325] [Article Influence: 110.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4748] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 141.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S, Reesink HW, Garg J. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ishikawa H, Watanabe H, Hu W. Dual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment options. J Hepatol. 2013;58:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lawitz E, Poordad F, Kowdley KV, Cohen DE, Podsadecki T, Siggelkow S, Larsen L, Menon R, Koev G, Tripathi R. A phase 2a trial of 12-week interferon-free therapy with two direct-acting antivirals (ABT-450/r, ABT-072) and ribavirin in IL28B C/C patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1. J Hepatol. 2013;59:18-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Trifan A, Stanciu C. Checkmate to liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5514-5520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miller ER, McNally S, Wallace J, Schlichthorst M. The ongoing impacts of hepatitis c--a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Braitstein P, Montessori V, Chan K, Montaner JS, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Quality of life, depression and fatigue among persons co-infected with HIV and hepatitis C: outcomes from a population-based cohort. AIDS Care. 2005;17:505-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Younossi Z, Kallman J, Kincaid J. The effects of HCV infection and management on health-related quality of life. Hepatology. 2007;45:806-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dieperink E, Willenbring M, Ho SB. Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with hepatitis C and interferon alpha: A review. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:867-876. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Schaefer M, Capuron L, Friebe A, Diez-Quevedo C, Robaeys G, Neri S, Foster GR, Kautz A, Forton D, Pariante CM. Hepatitis C infection, antiviral treatment and mental health: a European expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1379-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Johnson ME, Fisher DG, Fenaughty A, Theno SA. Hepatitis C virus and depression in drug users. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:785-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nguyen HA, Miller AI, Dieperink E, Willenbring ML, Tetrick LL, Durfee JM, Ewing SL, Ho SB. Spectrum of disease in U.S. veteran patients with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1813-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Almasio PL, Cottone C, D’Angelo F. Pegylated interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C: lights and shadows of an innovative treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39 Suppl 1:S88-S95. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Alvarez F. Therapy for chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Invest Med. 1996;19:381-388. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Evidence-informed assessment and treatment of depression in HCV and interferon-treated patients. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Valentine AD, Meyers CA. Neurobehavioral effects of interferon therapy. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7:391-395. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Golden J, O’Dwyer AM, Conroy RM. Depression and anxiety in patients with hepatitis C: prevalence, detection rates and risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:431-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Falasca K, Mancino P, Ucciferri C, Dalessandro M, Manzoli L, Pizzigallo E, Conti CM, Vecchiet J. Quality of life, depression, and cytokine patterns in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with antiviral therapy. Clin Invest Med. 2009;32:E212-E218. [PubMed] |

| 33. | von Ammon Cavanaugh S. Depression in the medically ill. Critical issues in diagnostic assessment. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:48-59. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Dan AA, Martin LM, Crone C, Ong JP, Farmer DW, Wise T, Robbins SC, Younossi ZM. Depression, anemia and health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Grundy G, Beeching N. Understanding social stigma in women with hepatitis C. Nurs Stand. 2004;19:35-39. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436-2441. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Paterson BL, Backmund M, Hirsch G, Yim C. The depiction of stigmatization in research about hepatitis C. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:364-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Schäfer M, Boetsch T, Laakmann G. Psychosis in a methadone-substituted patient during interferon-alpha treatment of hepatitis C. Addiction. 2000;95:1101-1104. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Kennedy D, Ryan G, Murphy DA, Elijah J, Schuster MA. HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and their families: a qualitative analysis. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:244-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Anti-Discrimination Board of New South Wales, 2001. Report of the inquiry into hepatitis C related discrimination. Available from: http://www.hep.org.au/documents/2001CChange-3MB.pdf. |

| 41. | Butt G. Stigma in the context of hepatitis C: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:712-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zickmund S, Ho EY, Masuda M, Ippolito L, LaBrecque DR. “They treated me like a leper”. Stigmatization and the quality of life of patients with hepatitis C. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:835-844. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Giordanino C, Sacco M, Ceretto S, Smedile A, Ciancio A, Cariti G, De Blasi T, Picciotto A, Marenco S, Grasso A. Durability of the response to peginterferon-α2b and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a cohort study in the routine clinical setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, Martinot M, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, Kilani A, Areias J, Auperin A, Benhamou JP. Long-term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:875-881. [PubMed] |

| 45. | García-Bengoechea M, Basaras M, Barrio J, Arrese E, Montalvo II, Arenas JI, Cisterna R. Late disappearance of hepatitis C virus RNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C in sustained response after alpha-interferon therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1902-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Marinho RT, Pinto RM, Santos ML, de Moura MC. Lymphocyte T helper-specific reactivity in sustained responders to interferon and ribavirin with negativation (seroreversion) of anti-hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2004;24:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | D’Ambrosio R, Aghemo A, Fraquelli M, Rumi MG, Donato MF, Paradis V, Bedossa P, Colombo M. The diagnostic accuracy of Fibroscan for cirrhosis is influenced by liver morphometry in HCV patients with a sustained virological response. J Hepatol. 2013;59:251-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Longo S, Cotella G, Carletta F, Catacchio M, Antonaci S. Perihepatic lymphadenopathy and the response to therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Ultrasound. 2010;13:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Muller P, Renou C, Harafa A, Jouve E, Kaplanski G, Ville E, Bertrand JJ, Masson C, Benderitter T, Halfon P. Lymph node enlargement within the hepatoduodenal ligament in patients with chronic hepatitis C reflects the immunological cellular response of the host. J Hepatol. 2003;39:807-813. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Trepo C, Lindsay K, Goodman Z, Ling MH, Albrecht J. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1303-1313. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Bruno S, Crosignani A, Facciotto C, Rossi S, Roffi L, Redaelli A, de Franchis R, Almasio PL, Maisonneuve P. Sustained virologic response prevents the development of esophageal varices in compensated, Child-Pugh class A hepatitis C virus-induced cirrhosis. A 12-year prospective follow-up study. Hepatology. 2010;51:2069-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ, Manns MP, Kuske L. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584-2593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1165] [Cited by in RCA: 1167] [Article Influence: 89.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Everson GT, Terrault NA, Lok AS, Rodrigo del R, Brown RS, Saab S, Shiffman ML, Al-Osaimi AM, Kulik LM, Gillespie BW. A randomized controlled trial of pretransplant antiviral therapy to prevent recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2013;57:1752-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sarkar S, Jiang Z, Evon DM, Wahed AS, Hoofnagle JH. Fatigue before, during and after antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C: results from the Virahep-C study. J Hepatol. 2012;57:946-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Terrault NA. Sexual activity as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:109-113. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int. 2012;32:880-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Koskinas J, Kilidireas C, Karandreas N, Kountouras D, Savvas S, Hadziyannis E, Archimandritis AJ. Severe hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinaemic sensory-motor polyneuropathy treated with pegylated interferon-a2b and ribavirin: clinical, laboratory and neurophysiological study. Liver Int. 2007;27:414-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Ito A, Kazama T, Ito K, Ito M. Purpura with cold urticaria in a patient with hepatitis C virus infection-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia type III: successful treatment with interferon-beta. J Dermatol. 2003;30:321-325. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Namba T, Shiba R, Yamamoto T, Hirai Y, Moriwaki T, Matsuda J, Kadoya H, Takeji M, Yamada Y, Yoshihara H. Successful treatment of HCV-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis with double-filtration plasmapheresis and interferon combination therapy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010;14:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, Delmas B, Valensi F, Cacoub P, Brechot C. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 597] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Nunes J, Tato Marinho R, Raposo J, Velosa J. [Influence of hepatitis C virus replication on splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes]. Acta Med Port. 2010;23:941-944. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Liu S, Cipriano LE, Holodniy M, Owens DK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. New protease inhibitors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Fujiwara K, Allison RD, Wang RY, Bare P, Matsuura K, Schechterly C, Murthy K, Marincola FM, Alter HJ. Investigation of residual hepatitis C virus in presumed recovered subjects. Hepatology. 2013;57:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |