Published online Jul 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4537

Revised: May 19, 2013

Accepted: June 8, 2013

Published online: July 28, 2013

Processing time: 226 Days and 20.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate clinical outcomes of patients that underwent surgery, transarterial embolization (TAE), or supportive care for spontaneously ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: A consecutive 54 patients who diagnosed as spontaneously ruptured HCC at our institution between 2003 and 2012 were retrospectively enrolled. HCC was diagnosed based on the diagnostic guidelines issued by the 2005 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. HCC rupture was defined as disruption of the peritumoral liver capsule with enhanced fluid collection in the perihepatic area adjacent to the HCC by dynamic liver computed tomography, and when abdominal paracentesis showed an ascitic red blood cell count of > 50000 mm3/mL in bloody fluid.

RESULTS: Of the 54 patients, 6 (11.1%) underwent surgery, 25 (46.3%) TAE, and 23 (42.6%) supportive care. The 2-, 4- and 6-mo cumulative survival rates at 2, 4 and 6 mo were significantly higher in the surgery (60%, 60% and 60%) or TAE (36%, 20% and 20%) groups than in the supportive care group (8.7%, 0% and 0%), respectively (each, P < 0.01), and tended to be higher in the surgical group than in the TAE group. Multivariate analysis showed that serum bilirubin (HR = 1.09, P < 0.01), creatinine (HR = 1.46, P = 0.04), and vasopressor requirement (HR = 2.37, P = 0.02) were significantly associated with post-treatment mortality, whereas surgery (HR = 0.41, P < 0.01), and TAE (HR = 0.13, P = 0.01) were inversely associated with post-treatment mortality.

CONCLUSION: Post-treatment survival after surgery or TAE was found to be better than after supportive care, and surgery tended to provide better survival benefit than TAE.

Core tip: We have shown here that overall survival rates of patients with ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is significantly higher in patients with surgery or transarterial embolization (TAE) than in those with supportive care, and tended to be higher in patients with surgery than in those with TAE. To date, there has been a dearth of reliable clinical evidence on the merits of surgical treatment versus those of TAE, in the context of survival benefit in patients with a spontaneous HCC rupture. Therefore, the present study may provide useful information for clinicians to determine the most appropriate treatment option for spontaneously ruptured HCC.

- Citation: Jin YJ, Lee JW, Park SW, Lee JI, Lee DH, Kim YS, Cho SG, Jeon YS, Lee KY, Ahn SI. Survival outcome of patients with spontaneously ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma treated surgically or by transarterial embolization. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(28): 4537-4544

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i28/4537.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4537

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the worldwide health problem and the third leading cause of cancer-related death globally[1-3]. Despite recent considerable advances in the understanding of tumor biology and the continued progression and development of diagnostic and therapeutic tools[4-7], the overall prognosis of HCC remains disappointing. In particular, due to its hypervascularity, HCC can exhibit rapid progression with direct invasion of surrounding tissues or it can invoke spontaneous tumor rupture[8]. HCC rupture is one of the life-threatening complications of HCC, and therefore, the most efficient treatment modality should be selected and rapidly applied to patients with ruptured HCC.

The incidence of spontaneous HCC rupture has decreased due to the earlier detection of HCC. Nevertheless, its incidence has been reported to be high as 3%-15% and its in-hospital mortality rate to range from 25% to 75% in the acute phase[9-12]. Open surgery was the main method used to treat HCC rupture from the 1960s to the 1980s[13-15]. Recently, survival benefit by transarterial embolization (TAE) has been reported[16-18]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no definite recommendation has been issued regarding optimal treatment of HCC rupture, and the comparative survival benefits of surgery and TAE remain unclear.

Therefore, in this retrospective study, we undertook to evaluate survival outcomes according to treatment modalities, that is, surgery, TAE, or supportive care, in patients with a spontaneously ruptured HCC, and sought to identify the factors that predispose post-treatment mortality in these patients.

Between August 2003 and February 2012, 1765 consecutive patients were initially diagnosed as having HCC at Inha University Hospital. Of these 1765 patients, 61 (3.5%) patients were clinically diagnosed as having spontaneously ruptured HCC. No patient had recent history of HCC treatment such as surgery or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) within one month prior to the diagnosis of HCC rupture. HCC was diagnosed according to the diagnostic guidelines issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[19]. HCC rupture was defined as disruption of the peritumoral liver capsule with enhanced fluid collection in the perihepatic area adjacent to the HCC by dynamic liver computed tomography (CT)[20], and when abdominal paracentesis showed an ascitic red blood cell count of > 50000 mm3/mL in bloody fluid[21,22].

Of the 61 patients, 4 patients were excluded because they underwent two-staged surgical treatment after TAE for ruptured HCC (n = 3) and they had concurrent malignancy (gastric cancer, n = 1). Three patients were also excluded because they did not meet the diagnostic criteria of a ruptured HCC although HCC rupture was clinically suspected based on right upper quadrant abdominal pain and a reduced serum hemoglobin level. Therefore, 54 patients finally constituted the study cohort and their retrospective database was analyzed.

Database information at time of diagnosis of ruptured HCC was reviewed: age, gender; vital signs; medical history; white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and platelet count; international normalized ratio (INR); serum alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine; viral hepatitis findings including hepatitis B surface antigen, and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody findings; serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus; alpha-fetoprotein; and vasopressor requirement. Furthermore, we evaluated HCC tumor statuses namely tumor number, size, presence of portal vein tumor thrombosis, and presence of extra-hepatic metastasis. Intrahepatic HCC lesion size was recorded as the longest diameter of the largest lesion in at least one dimension. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed based on clinical evidence of portal hypertension (encephalopathy, esophageal varices, ascites, splenomegaly, or platelet count < 100000/mm3)[23] or by previously performed ultrasonography[24]. Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores were assessed, and HCC staging was performed using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system[25].

Immediately following a diagnosis of HCC rupture, patients were transferred to an intensive care unit. At time of HCC rupture, liver functions can be much more aggravated by hemorrhage or shock than after the condition was relatively well controlled. Therefore, frequent assessments of liver function were required concurrently with volume replacement and coagulopathy correction, and liver function was closely monitored before definite treatment decision making. Norepinephrine was infused intravenously as the primary vasopressor if shock event developed, and all 54 patients were administered 3rd generation cephalosporin antimicrobial therapy.

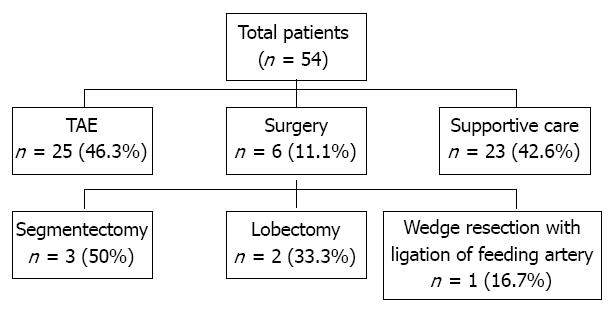

The need for emergency hemostasis, such as, open surgery or TAE, was explained to all patients in the absence of a contraindication and their family members. They were informed of the risks and benefits of emergency surgery or TAE in detail. To avoid any coercion, written informed consent was obtained from all patients and a family member before intervention of hemostasis. The follow were viewed as surgical contraindication: the presence of poorly controlled chronic ascites; the presence of poorly controlled chronic hepatic encephalopathy; the presence of a poor liver function; or a poor performance status. Of the 54 patients enrolled, 6 (11.1%) underwent surgery and 25 (46.3%) TAE, and the remaining 23 (42.6%) patients received supportive care without hemostatic intervention (Figure 1). Successful control of hemorrhage was defined as hemodynamic stabilization, a normal hemoglobin level, and no requirement for further transfusion. During follow-up period after treatment, dynamic liver CT images and serum alpha-fetoprotein levels were obtained every 1-3 mo.

TAE group: In hemodynamically unstable patients with an obvious continuous hemorrhage, TAE was considered if reserved liver function was relatively good regardless of the correction of coagulopathy. Briefly, the tumor location, the active bleeding site, and portal vein patency were determined angiographically. Thereafter, embolization of the feeding artery was performed with gelfoam, which is the small cube of approximately 1 mm3 sized absorbable gelatin sponge particles. Two patients who underwent TACE were included in the TAE group. However, TACE/TAE was not performed if the main portal vein was completely occluded by tumor thrombus.

Surgical group: After stabilizing hemodynamic status by volume replacement and transfusion, patients underwent a full clinical assessment to evaluate the possibility of surgical treatment. Segmentectomy with perihepatic packing (n = 3, 50%), lobectomy (n = 2, 33.3%), or liver wedge resection with feeding artery ligation (n = 1, 16.7%) were performed depending on circumstances (Figure 1).

Supportive care group: Patients contraindicated for surgery or TACE/TAE received only vigorous and careful conservative treatments with replacement of blood or albumin, correction of coagulopathy, antimicrobial therapy, and analgesics, diuretics, etc.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Inha University Hospital, Incheon 400-711, South Korea.

The baseline characteristics of patients are expressed as medians (ranges) and frequencies. Differences between categorical or continuous variables were analyzed using the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Student’s t test. Post-treatment cumulative mortality rates were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and group differences were compared using the log-rank test. In patients that received supportive care, survival was defined from diagnosis of HCC rupture to patients’ death. Multivariate analysis was performed using a Cox regression hazard model to identify predictors of post-treatment mortality in patients with spontaneously ruptured HCC. Two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSSv18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

The baseline characteristics of the 54 patients are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 54 years (range, 30-87 years) and 47 (87.0%) were male. The most common etiology of HCC was hepatitis B virus infection, which was observed in 36 (66.7%) patients. Of the 54 patients, 6 (11.1%) were of CTP class A, 23 (42.6%) were of CTP class B, and 5 (46.3%) were of CTP class C. Eleven (20.4%) of the 54 patients had a single HCC and 43 (79.6%) patients had multiple HCC. Median tumor size was 8.5 cm (range, 2.9-25.5 cm), and 4 (7.4%) patient had HCCs within Milan criteria. Forty-seven (87.7%) patients had nodular type HCC. Before treatment, 0 (0%), 5 (9.3%), 9 (16.7%), 15 (27.8%), and 25 (46.3%) patients were found to have BCLC 0, A, B, C, or D stage HCC, respectively. Median alpha-fetoprotein concentration at diagnosis of HCC rupture was 1158 ng/mL (range, 3.0 × 104-6.1 × 104 ng/mL). Thirteen (24.1%) patients required a vasopressor due to shock at presentation. Ruptured HCC was located on the surface of liver in all the patients.

| Variable | Total (n = 54) |

| Age1, yr | 54 (30-87) |

| Gender (male) | 47 (87.0) |

| Etiology | |

| HBV/HCV/alcohol/others | 36 (66.7)/6 (11.1)/7 (13.0)/5 (9.3) |

| CTP classification | |

| A/B/C | 6 (11.1)/23 (42.6)/25 (46.3) |

| Tumor size1, cm | 8.5 (2.9-25.5) |

| Tumor number | |

| Single/multiple | 11 (20.4)/43 (79.6) |

| Tumor type | |

| Nodular/infiltrative | 47 (87.0)/7 (13.0) |

| Within Milan criteria | 4 (7.4) |

| BCLC stage | |

| 0/A/B/C/D | 0 (0.0)/3 (5.6)/8 (14.8)/15 (27.8)/28 (51.9) |

| Vasopressor requirement | 13 (24.0) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein1, ng/mL | 1158 (3.0 × 104-6.1 × 104) |

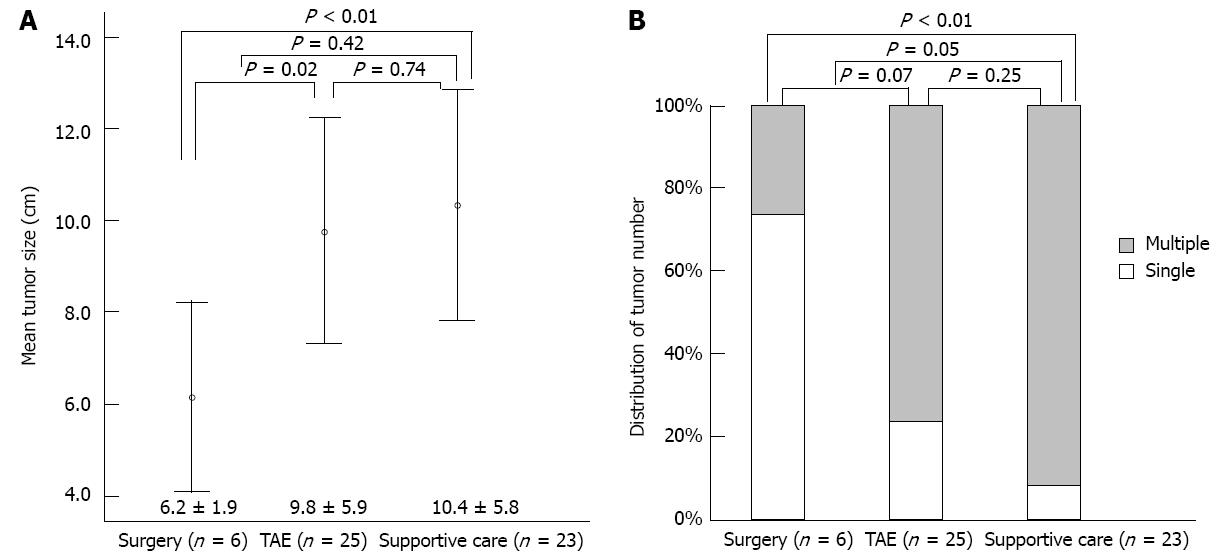

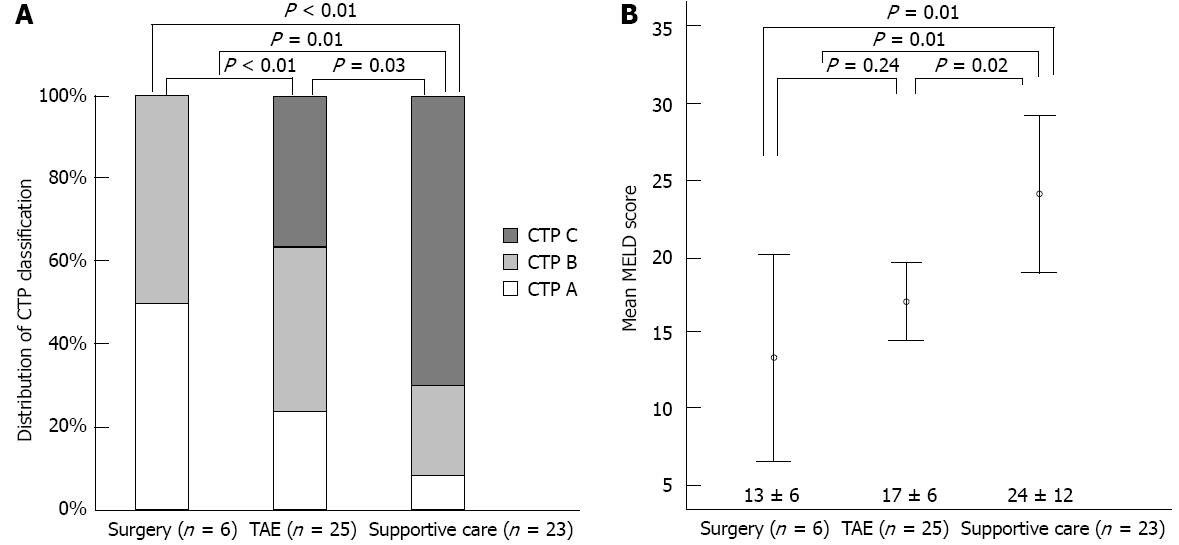

Clinical variables in the three treatment groups are summarized in Figures 2 and 3, and Table 2. Mean tumor size was significantly smaller in the surgical group than in the TAE (P = 0.02) or supportive care (P < 0.01) groups (Figure 2A). The single tumor rate was significantly higher in the surgical group than in the supportive care group (P < 0.01) (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the surgical group had better reserve hepatic function (CTP class) than the other two groups (both P < 0.01) (Figure 3A). Mean MELD score was higher in the supportive care group than in the other two groups (both P = 0.01), but was not different in the surgical and TAE groups (P = 0.24) (Figure 3B).

| Variables | Resection | TAE | Supportive | P value |

| 6 (11.1) | 25 (46.3) | 23 (42.6) | ||

| Age, yr | 59 (42-79) | 54 (30-83) | 53 (36-87) | NS |

| Gender (male) | 5 (83.3) | 22 (88.0) | 20 (86.9) | 0.95 |

| Hb1, g/dL | 8.2 (5.1-12.1) | 7.6 (4.5-11.2) | 8.1 (2.9-13.6) | NS |

| Platelet1, × 103/mm3 | 127.5 (80-236) | 139 (11-534) | 191 (86-606) | 0.034, NS |

| Prothrombin time1, INR | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | 1.3 (1.0-2.3) | 2.2 (1.0-6.6) | NS |

| Albumin1, mg/dL | 2.6 (0.4-3.5) | 2.9 (1.8-3.7) | 2.6 (1.2-4.3) | NS |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 2.3 (0.5-6.2) | 1.2 (0.4-5.4) | 6.7 (0.6-23.0) | < 0.014 , NS |

| Creatinine1, mg/dL | 1.2 (0.8-2.0) | 1.1 (0.6-1.2) | 1.9 (0.9-4.9) | < 0.014, 0.015 |

| Tumor type | ||||

| Nodular/infiltrative | 5/1 (83.3/16.7) | 21/4 (84/16) | 21/2 (91.3/8.7) | 0.72 |

| BCLC stage A/B/C/D | 3/2/12/0 (50.0/33.3/16.7/0) | 0/4/9/12 (0/16/36/48) | 0/2/5/16 (0/8.7/21.7/69.6) | < 0.01 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein1, ng/mL | 33.9 (3-3.6 × 104) | 1345 (3-6.1 × 104) | 1389 (19-6.1 × 104) | NS |

| Vasopressor requirement | 1 (16.7) | 7 (28.0) | 5 (21.7) | 0.79 |

| Incomplete hemostasis | 1 (16.7) | 5 (20) | NA | 1.003 |

| Post-treatment liver failure | 0 (0) | 6 (24) | NA | 0.313 |

| Rebleeding | 0/5 (0) | 1/20 (5.0) | NA | 1.003\ |

Serum platelet count (P = 0.03), total bilirubin (P < 0.01), and creatinine levels (P < 0.01) were significantly lower in surgical group than supportive care group (Table 2). The other clinical parameters including age, gender, and tumor type showed no difference among three treatment groups. Incomplete hemostasis occurred in 1 (16.7%) patient in the surgical group and in 5 (20%) patients in the TAE group (P = 1.00), and post-treatment liver failure occurred in 0 (0%) patient in the surgical group and in 1 (5%) patient in the TAE group (P = 0.31). Rebleeding after complete hemostasis was observed in 0 (0%) patients in the surgical group and in 1 (5%) patient in the TAE group (P = 1.00), and they received supportive care (Table 2).

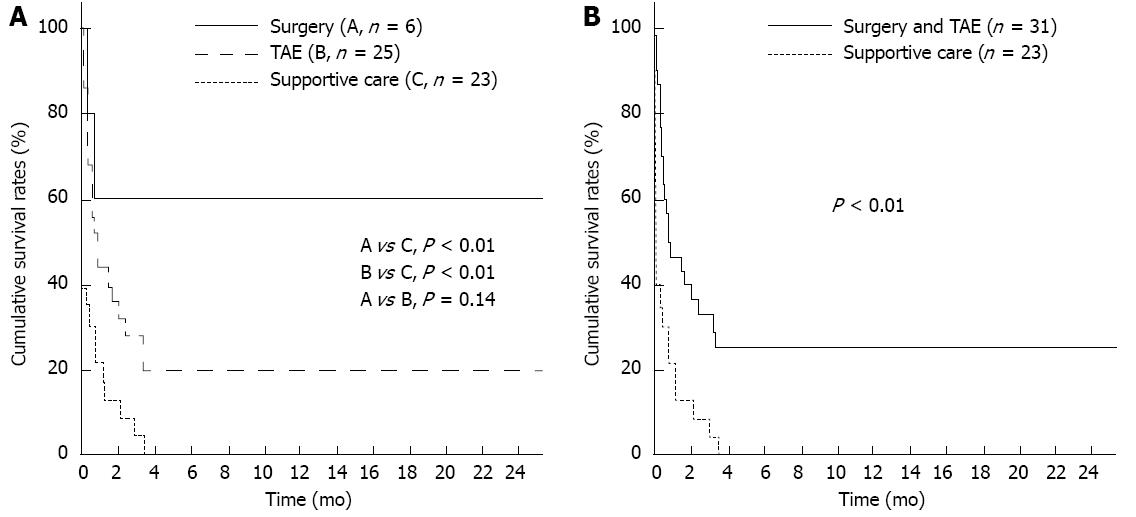

One-month overall cumulative mortality for the 54 study subjects was 63.8%. Cumulative survival rates at 2-, 4- and 6-mo were 60.0%, 60.0% and 60.0%, respectively, in the surgical group and 36.0%, 20.0% and 20.0%, respectively in the TAE group, and 8.7%, 0% and 0%, respectively in the supportive care group (each, P < 0.01). Cumulative survival rates at 2-, 4- and 6-mo were tended to be higher in the surgical group than in the TAE group despite the statistical insignificance (P = 0.14) (Figure 4A). Cumulative survival rates at 2-, 4- and 6-mo were 50.2%, 40.1% and 33.1%, respectively in the intervention group such as surgery or TAE, and 8.7%, 0% and 0%, respectively, in the supportive care group (P < 0.01) (Figure 4B).

Multivariate analysis showed that surgery (HR = 0.41, P < 0.01), and TAE (HR = 0.13, P = 0.01) were inversely associated with post-treatment mortality in ruptured HCC patients. Serum bilirubin (HR = 1.09, P < 0.01), creatinine (HR = 1.46, P = 0.04), and vasopressor use (HR = 2.37, P = 0.02) were positively associated with post-treatment mortality. Age, gender, INR, albumin, tumor size, and tumor number were not found to be associated with post-treatment mortality (Table 3).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis1 | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age, yr | 0.99 | 0.96-1.01 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.14 |

| Gender (male) | 0.88 | 0.37-2.09 | 0.77 | - | - | - |

| INR | 1.77 | 1.30-2.41 | < 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.49-1.70 | 0.79 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.13 | 1.07-1.19 | < 0.01 | 1.09 | 1.13-1.15 | < 0.01 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 0.73 | 0.42-1.03 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.49-1.32 | 0.39 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.86 | 1.33-2.61 | < 0.01 | 1.46 | 1.01-2.13 | 0.04 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.21 | - | - | - |

| Tumor number multiple vs single | 2.45 | 1.09-5.54 | 0.03 | 1.14 | 0.46-2.83 | 0.78 |

| Tumor size, cm | 1.01 | 0.96-1.05 | 0.88 | - | - | - |

| Vasopressor requirement | 1.96 | 1.87-3.29 | 0.01 | 2.37 | 1.13-4.96 | 0.02 |

| Treatment type | ||||||

| Supportive care (control) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TACE/TAE | 0.44 | 0.03-0.64 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03-0.66 | 0.01 |

| Surgery | 0.15 | 0.24-0.80 | < 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.21-0.79 | < 0.01 |

We have shown here that overall survival rates of patients with ruptured HCC is significantly higher in patients with surgery or TAE than in those with supportive care, and tended to be higher in patients with surgery than in those with TAE. Furthermore, high serum bilirubin and creatinine levels, and vasopressor requirement were found to be significantly associated with post-treatment mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the survival benefit of surgery vs TAE. Although several previous studies have evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of surgery or TAE, in patients with spontaneous HCC rupture, direct comparative information is little available regarding survival outcomes after surgery and TAE in such patients.

Spontaneous HCC rupture is likely to occur in patients with advanced staged HCC with reported incidences of 10.0% in Japan[15], 12.4% in Thailand[10], and about 3.0% in the United Kingdom[26]. In the present study, the estimated incidence of spontaneous HCC rupture was 3.5%, and the overall 1-mo mortality was a high as 64% in our cohort, which are the similar to the outcomes of previous studies[10,11,27]. However, despite its high mortality, survival benefits for surgical treatment[13-15] and for TAE[16-18] have been reported in patients with a spontaneous HCC rupture. Likewise, in the present study, the overall survivals of patients with surgery or TAE were significantly higher than that in those with supportive care, especially in those in a hemodynamically stable state with a low serum bilirubin level, and good renal function. However, to date, there has been a dearth of reliable clinical evidence on the merits of surgical treatment versus those of TAE, in the context of survival benefit in patients with a spontaneous HCC rupture. Therefore, the present study may provide useful information for clinicians to determine the most appropriate treatment option for spontaneously ruptured HCC.

Ruptured HCC is a catastrophic disorder characterized by fatal complications, such as, coagulopathy, hemodynamic instability, or liver insufficiency. Thus, treatment should be considered carefully based on adequate information. As has been found in previous studies[13-15], surgical treatment was found to provide significant survival benefit as compared with supportive care in the current study. Furthermore, surgical group had relatively better hepatic function reserve, smaller tumors, and smaller numbers of tumors than the supportive care groups, although bias might have been introduced by selection for surgery. Nonetheless, the cumulative overall survival rate was higher in surgical group than in the supportive care group, and surgical treatment was found to be independent predictor of post-treatment survival by multivariate analysis. Although not all patients could have undergone surgery due to a poor hepatic function or an unstable vital status, surgical hemostasis can be considered if hepatic dysfunction or hemodynamic instability can be maximally corrected immediately after initial rupture of a hepatoma. Furthermore, post-surgical complications need to be considered before treatment decision-making despite the absence of an immediate severe complication after surgical intervention in the present study.

It has been reported that TAE is effective in achieving immediate hemostasis for ruptured HCC. In the present study, the overall survival rate was better in the TAE group than in the supportive care group. Advanced angiographic techniques enable the tumor location, active bleeding focus, and portal vein patency to be assessed, but life-threatening complications, such as, liver failure can developed after TAE, at rates ranging from 12% to 34%[12,17]. In the present study, post-TAE liver failure and technical failure for immediate hemostasis was observed in 6 (24%) and 5 (20%) patients of the TAE group, respectively, which suggests that TAE should be selectively administered in patients with good reserved hepatic function, tolerable coagulopathy, and a patent main portal vein.

In terms of comparison of survival benefits between the surgical and TAE groups, the current study failed to show a significant difference, although the cumulative overall survival rate tended to be higher in the surgical treatment group. Although TAE is less invasive than open surgical hemostasis, we suppose that open surgical treatment offer a higher chance of successfully achieving hemostasis by removing the bleeding focus or by allowing complete ligation of feeding artery. In previous studies, the 30-d mortality rate after TAE group has been reported to be lower than that after open surgical group[12,17,28]. However, in the present study, cumulative overall 1-mo survival rates were statistically similar between two groups. Moreover, at 1 mo after operative treatment, cumulative survival was clinically higher in the surgical group than in the TAE group despite the statistical insignificance (Figure 4). However, it should be borne in mind that this lack of significance may have been due to small patient numbers. Therefore, large number of patients who underwent surgical treatment need to be evaluated in the comparative study in the future.

Patients with a poor liver function reserve cannot tolerate surgical resection or aggressive angiographic intervention. Therefore, CTP class or MELD score, which reflect reserved hepatic function, could be important pretreatment factors. However, in the present study, of variables comprising the CTP class, only serum bilirubin was found to be independently associated with post-treatment survival. Likewise, of the variables comprising the MELD scores, only serum bilirubin and creatinine were found to be independent factors. Therefore, we estimated individual variables of CTP class or MELD score to avoid overestimation of the other factors in the multivariate analysis of post-treatment survival in patients with spontaneous HCC rupture.

Elevated serum creatinine and vasopressor requirements are likely to reflect multiorgan failure[29], and decreased effective circulating volume or the presence of superimposed infection may induce alterations in organ perfusion and in hemodynamic stability. Moreover, inflammatory reactions triggered by hepatocellular necrosis after HCC rupture may contribute to liver insufficiency, and subsequent multiorgan failure. Although decreased serum albumin level and a prolonged prothrombin time suggest reduced liver synthetic function, they can be corrected by albumin and coagulation factor replacement. On the other hand, serum bilirubin level cannot be rapidly and artificially corrected immediately after parenchymal liver damage. Therefore, serum bilirubin may be an independent factor of patient survival, unlike serum albumin or INR. Furthermore, the importance of serum bilirubin level in patients with HCC rupture has been previously reported[17,30]. However, during treatment decision-making, age, INR, albumin, and tumor size and number may also be clinically important variables despite their lack of statistical significance in the present study.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study is inherently limited by its retrospective study design. However, we enrolled all eligible patients. Second, the varied clinical and tumor statuses of patients and the critical disease status prevented randomization, and probably introduced bias. Furthermore, it takes long time to collect the prospective database of patients due to low incidence of the disease. Third, the absolute number of patients who underwent surgery was small, and therefore, there might be no significant difference in cumulative survival rate between surgery and TAE groups. Accordingly, we suggest a large-scale study be conducted to confirm our study.

In conclusions, the present study suggests that the post-treatment outcomes of surgery or TAE are better than that of supportive care in patients with spontaneous HCC rupture, and that surgical hemostasis might provide better survival benefit than TAE. However, we advise that serum bilirubin, creatinine, and hemodynamic status should be considered during treatment decision making. Regardless of its shortcomings, we believe that the present study would provide important information that aids decision making in patients with spontaneous HCC rupture.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) rupture is one of the life-threatening complications of HCC, and therefore, the most efficient treatment modality should be selected and rapidly applied to patients with ruptured HCC.

Recently, survival benefit by transarterial embolization (TAE) has been reported. However, no definite recommendation has been issued regarding optimal treatment of HCC rupture, and the comparative survival benefits of surgery and TAE remain unclear.

The present study suggests that the post-treatment outcomes of surgery or TAE are better than that of supportive care in patients with spontaneous HCC rupture, and that surgical hemostasis might provide better survival benefit than TAE.

This study may provide useful information for clinicians to determine the most appropriate treatment option for spontaneously ruptured HCC.

It is a rare situation specially for Western Europe, so it is good to know the experience of the group.

P- Reviewer Marinho RT S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533-543. [PubMed] |

| 2. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S27-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 738] [Cited by in RCA: 722] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bosch FX, Ribes J, Díaz M, Cléries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S5-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1799] [Cited by in RCA: 1816] [Article Influence: 86.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zucman-Rossi J, Jeannot E, Nhieu JT, Scoazec JY, Guettier C, Rebouissou S, Bacq Y, Leteurtre E, Paradis V, Michalak S. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hepatocellular adenoma: new classification and relationship with HCC. Hepatology. 2006;43:515-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 606] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mueller GC, Hussain HK, Carlos RC, Nghiem HV, Francis IR. Effectiveness of MR imaging in characterizing small hepatic lesions: routine versus expert interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:673-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim SH, Kim SH, Lee J, Kim MJ, Jeon YH, Park Y, Choi D, Lee WJ, Lim HK. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI versus triple-phase MDCT for the preoperative detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1675-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Ng IO, Liu CL, Lam CM, Wong J. Improving survival results after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study of 377 patients over 10 years. Ann Surg. 2001;234:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yuki K, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M, Kanai T, Shimosato Y. Growth and spread of hepatocellular carcinoma. A review of 240 consecutive autopsy cases. Cancer. 1990;66:2174-2179. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Aoki T, Kokudo N, Matsuyama Y, Izumi N, Ichida T, Kudo M, Ku Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Matsui O, Makuuchi M; for the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Prognostic Impact of Spontaneous Tumor Rupture in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Analysis of 1160 Cases From a Nationwide Survey. Ann Surg. 2013;Mar 8; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chearanai O, Plengvanit U, Asavanich C, Damrongsak D, Sindhvananda K, Boonyapisit S. Spontaneous rupture of primary hepatoma: report of 63 cases with particular reference to the pathogenesis and rationale treatment by hepatic artery ligation. Cancer. 1983;51:1532-1536. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Leung KL, Lau WY, Lai PB, Yiu RY, Meng WC, Leow CK. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: conservative management and selective intervention. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1103-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Poon RT, Lam CM, Wong J. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single-center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3725-3732. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chiappa A, Zbar A, Audisio RA, Paties C, Bertani E, Staudacher C. Emergency liver resection for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1145-1150. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cherqui D, Panis Y, Rotman N, Fagniez PL. Emergency liver resection for spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:747-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miyamoto M, Sudo T, Kuyama T. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of 172 Japanese cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:67-71. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kirikoshi H, Saito S, Yoneda M, Fujita K, Mawatari H, Uchiyama T, Higurashi T, Imajo K, Sakaguchi T, Atsukawa K. Outcomes and factors influencing survival in cirrhotic cases with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ngan H, Tso WK, Lai CL, Fan ST. The role of hepatic arterial embolization in the treatment of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:338-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lau KY, Wong TP, Wong WW, Tan LT, Chan JK, Lee AS. Emergency embolization of spontaneous ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation between survival and Child-Pugh classification. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pombo F, Arrojo L, Perez-Fontan J. Haemoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: CT diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:321-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim JY, Lee JS, Oh DH, Yim YH, Lee HK. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization confers survival benefit in patients with a spontaneously ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:640-645. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hirai K, Kawazoe Y, Yamashita K, Kumagai M, Nagata K, Kawaguchi S, Abe M, Tanikawa K. Transcatheter arterial embolization for spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:275-279. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bruix J, Castells A, Bosch J, Feu F, Fuster J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Visa J, Bru C, Rodés J. Surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic value of preoperative portal pressure. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1018-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Di Lelio A, Cestari C, Lomazzi A, Beretta L. Cirrhosis: diagnosis with sonographic study of the liver surface. Radiology. 1989;172:389-392. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3241] [Cited by in RCA: 3282] [Article Influence: 149.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Clarkston W, Inciardi M, Kirkpatrick S, McEwen G, Ediger S, Schubert T. Acute hemoperitoneum from rupture of a hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nouchi T, Nishimura M, Maeda M, Funatsu T, Hasumura Y, Takeuchi J. Transcatheter arterial embolization of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma associated with liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:1137-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen MF, Jan YY, Lee TY. Transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization followed by hepatic resection for the spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1986;58:332-335. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Riordan SM, Williams R. Mechanisms of hepatocyte injury, multiorgan failure, and prognostic criteria in acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:203-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Leung CS, Tang CN, Fung KH, Li MK. A retrospective review of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolisation for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002;47:685-688. [PubMed] |