Published online May 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2727

Revised: March 26, 2013

Accepted: March 28, 2013

Published online: May 7, 2013

Processing time: 89 Days and 21.3 Hours

Although the introduction of double-balloon enteroscopy has greatly improved the diagnostic rate, definite diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum far from the ileocecal valve is still impossible in most cases. We explored the role of magnetic resonance (MR) enterography in detecting bleeding from Meckel’s diverticulum that can not be confirmed via double-balloon enteroscopy. This study describes a case of male patient with bleeding from Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosed with MR enterography of the small intestine. No bleeding lesion was found via colonoscopy, anal enteroscopy, or oral colonoscopy. MR enterography of the small intestine revealed an occupying lesion of 3.0 cm in the lower segment of the ileum. The patient was transferred to the Department of Abdominal Surgery of our hospital for surgical treatment. During surgery, a mass of 3 cm × 2 cm was found 150 cm from the ileocecal valve, in conjunction with congestion and edema of the corresponding mesangium. Intraoperative diagnosis was small bowel diverticulum with bleeding. The patient underwent partial resection of the small intestine. Postoperative pathology showed Meckel’s diverticulum containing pancreatic tissues. He was cured and discharged 7 d after operation. We conclude that MR enterography of the small intestine has greatly improved the diagnosis rate of Meckel’s diverticulum, particularly in those patients with the disease which can not be confirmed via double-balloon enteroscopy.

Core tip: This study describes a case of male patient with bleeding from Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosed with magnetic resonance (MR) enterography of the small intestine. MR enterography of the small intestine has greatly improved the diagnosis rate of Meckel’s diverticulum, particularly in those patients with the disease which can not be confirmed via double-balloon enteroscopy.

- Citation: Zhou FR, Huang LY, Xie HZ. Meckel’s diverticulum bleeding diagnosed with magnetic resonance enterography: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(17): 2727-2730

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i17/2727.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2727

Gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown cause is mostly a result of lesions located in the small intestine, for which the diagnosis and treatment can be challenging[1,2]. Meckel’s diverticulum is a common congenital malformation of the small intestine, with gastrointestinal bleeding being the most common symptom. Preoperative diagnosis of this condition is difficult. Although the introduction of double-balloon enteroscopy has greatly improved the diagnostic rate, definite diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum far from the ileocecal valve is still impossible in most cases. This study describes a case of bleeding from Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosed with magnetic resonance (MR) enterography of the small intestine in our department.

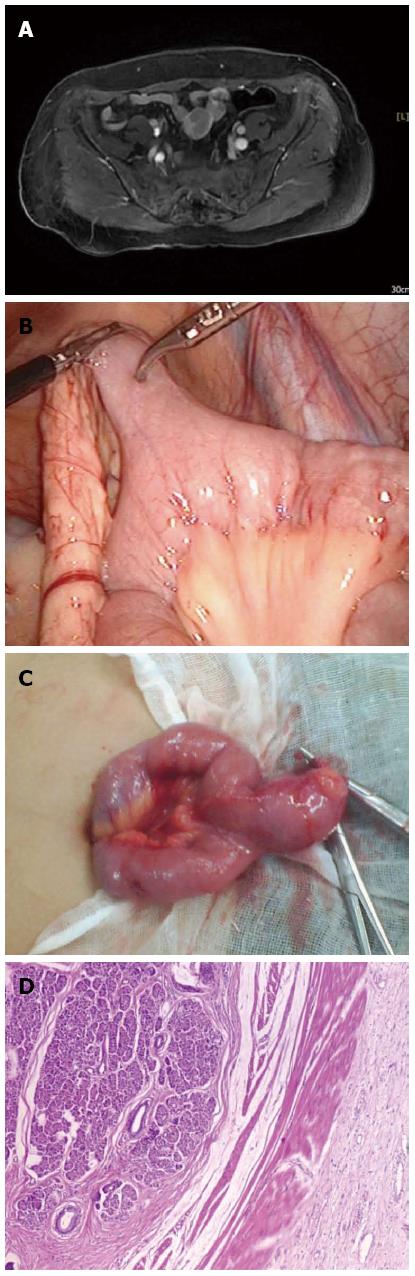

A 25-year-old man was first admitted to the hospital for lower abdominal pain on March 25, 2011. No abnormality was found through enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the whole abdomen on admission. No positive finding was reported on anal enteroscopy. Barium meal examination of the entire digestive tract showed multiple fluid levels in segments 4 and 5 of the small intestine. His condition improved with anti-inflammatory therapy, intestinal spasmolysis, and nutritional support. He was then discharged on April 3, 2011. After that, he was diagnosed as having “appendicitis” and underwent appendectomy in a local hospital. Encapsulated fluid was present in the right lower quadrant, which was improved after puncture and drainage. Later, he was again admitted to our hospital on February 17, 2012 due to melena for two days after recurrent abdominal pain for nearly a year. Examinations on admission showed a positive fecal occult blood test, stool red blood cell (RBC) +++/HP, C-reactive protein: 30.9 mg/L; abdominal CT revealed a small amount of fluid in the pelvic cavity. Routine examination of the ascites fluid collected by ultrasound-guided puncture showed red fluid, specific gravity > 1.018, positive Rivalta test, RBC ++++/HP, and nucleated cell count of 1.8 × 109/L. Ascites smears revealed no acid-fast bacilli. Bacterial culture indicated Streptococcus sanguis. No bleeding lesion was found via colonoscopy, anal enteroscopy, or oral colonoscopy. His condition improved after hemostatic, anti-infective and symptomatic treatment, and he was discharged on March 4, 2012. His condition remained stable after discharge until three days prior to admission when he experienced lower abdominal pain after eating spicy food, and had dark red bloody stools, 2-3 times a day. He was admitted for a third time on April 24, 2012. Blood tests upon admission showed hemoglobin (HGB) of 96 g/L; MR enterography of the small intestine showed an occupying lesion of 3.0 cm in the lower segment of the ileum. He was transferred to the Department of Abdominal Surgery for surgical treatment. During surgery, a mass of 3 cm × 2 cm was found 150 cm from the ileocecal valve, in conjunction with congestion and edema of the corresponding mesangium. Intraoperative diagnosis was small bowel diverticulum with bleeding. Postoperative pathology showed Meckel’s diverticulum containing pancreatic tissues. The patient underwent partial resection of the small intestine, and was cured and discharged 7 d after operation (Figure 1).

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the small intestine, with an incidence of 1% to 4%[3]. It usually occurs in the ileum within 100 cm of the ileocecal valve[4], and is a true diverticulum consisting of all layers of the bowel wall. Meckel’s diverticulum harbors various ectopic tissues, with gastric mucosa being the most common (about 50%), followed by pancreatic tissues (about 5%)[5]. The majority of people afflicted with Meckel’s diverticulum are asymptomatic, and 4% to 6% of the patients are detected due to symptoms of related complications[6-10]. Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common symptom of Meckel’s diverticulum[11], followed by intussusception, and intestinal obstruction.

Such bleeding occurs from larger vessels invaded by erosion and ulceration of normal intestinal mucosa in the diverticulum, as a result of the secretion of gastric acid or alkaline pancreatic fluid from the ectopic mucosa[12-15]. Consisting mainly of fundic glands, where parietal cells secrete gastric acid and chief cells secrete pepsin, the ectopic gastric mucosa is closely related to gastrointestinal bleeding, as the acid does not only directly cause corrosion of the diverticulum and intestinal mucosa, but also promotes the conversion of pepsinogen secreted by ectopic chief cells into pepsin, which in turn induces tissue digestion and leads to ulceration and bleeding.

Preoperative diagnosis is difficult when Meckel’s diverticulum is complicated by small intestinal bleeding[15]. Gastroscopy, colonoscopy, barium meal and ultrasound lack specificity, but they can be used to exclude lower gastrointestinal bleeding from other sites. Due to its high-density resolution, CT scanning can detect and accurately locate stones of low density in Meckel’s diverticulum[16,17]. CT enterography of the small intestine has been proven to be more useful than conventional CT in patients suspected of having small bowel lesions, as it not only maximizes the visibility of the mucosa and intestine structure with the aid of contrast agents, but also detects parenteral abnormalities[18-22]. MR enterography is a radiation-free technique developed based on CT enterography, which allows evaluation of intestinal functionalities using MR fluoroscopy.

MR enterography is a novel technique that combines the advantages of both the conventional enterography and the morphological imaging of magnetic resonance imaging, thus making it an examination for both the functions and the morphologies of small intestine. Before MR enterography is done, the bowel must be completely cleansed and the intestinal canal distended. Therefore, it is critically important to select a contrast agent that can thoroughly distend the intestinal canal and clearly demonstrate the enteric cavity and intestinal wall, and does not produce artifacts or pose a hazard to human health. Although the double-contrast imaging of the small intestine is helpful for observing the early mucosal changes, it cannot visualize the lesions around the intestinal wall or in the mesentery. In contrast, MR enterography, with three-dimensional imaging capabilities and excellent soft-tissue contrast, can be used to observe the mucosa and analyze the changes around the intestinal canal[23-25].

The introduction of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy has made observation of the entire small bowel mucosa possible, and the latter technique also enables biopsy for pathological diagnosis and endoscopic treatment[26-28]. Compared with traditional push enteroscopy (90-150 cm) and retrograde terminal ileoscopy (50-80 cm), double-balloon enteroscopy has a longer average depth (240-360 cm orally and 102-140 cm anally); compared with capsule endoscopy, it enables more pathological and endoscopic applications, such as hemostasis, polypectomy, dilatation treatment, and removal of foreign substances[29,30]. Heine et al[31] demonstrated in their study that double-balloon enteroscopy has a diagnosis rate of 63% for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, and complete small bowel examination is achievable for about 1/3 of these cases.

Although double-balloon enteroscopy has a high diagnosis rate for unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, since a complete small bowel examination can be done in only a few patients, the causes of bleeding still remain unknown in many other patients before surgery. In the present case, the lesion was up to 150 cm from the ileocecal valve, which was undetectable by anal colonoscopy with an average insertion depth of about 102-140 cm, therefore, no definite diagnosis could be made. In view of this, MR enterography of the small intestine was performed and an occupying lesion of 3.0 cm was found in the lower segment of the ileum, with clear boundaries, showing mixed signals. He was transferred to the Department of Abdominal Surgery for surgical treatment. During surgery, a mass of 3 cm × 2 cm was found 150 cm from the ileocecal valve, in conjunction with congestion and edema of the corresponding mesangium. Intraoperative diagnosis was small bowel diverticulum with bleeding. Postoperative pathology showed Meckel’s diverticulum containing pancreatic tissues. The patient underwent partial resection of the small intestine, and was cured and discharged 7 d after operation.

In summary, Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the small intestine that is easily complicated by small intestinal bleeding, for which preoperative diagnosis is difficult. The introduction of double-balloon enteroscopy has greatly improved the diagnostic rate, but definite diagnosis is still challenging in some patients, especially when the lesion is far from the ileocecal valve. MR enterography is a radiation-free technique developed based on CT enterography, which maximizes the visibility of the mucosa and intestine structure with the aid of contrast agents. MR enterography of the small intestine has greatly improved the diagnosis rate of Meckel’s diverticulum, particularly in those patients with the disease which can not be confirmed via double-balloon enteroscopy.

P- Reviewers Alkan M, Sozen S S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin S, Rockey DC. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:679-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zinner MJ, Schwartz SI, Ellis H. Maingot’s Abdominal operations. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 1997; 593-616. |

| 4. | Karadeniz Cakmak G, Emre AU, Tascilar O, Bektaş S, Uçan BH, Irkorucu O, Karakaya K, Ustundag Y, Comert M. Lipoma within inverted Meckel's diverticulum as a cause of recurrent partial intestinal obstruction and hemorrhage: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1141-1143. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Dujardin M, de Beeck BO, Osteaux M. Inverted Meckel’s diverticulum as a leading point for ileoileal intussusception in an adult: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:563-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matthews P, Tredgett MW, Balsitis M. Small bowel strangulation and infarction: an unusual complication of Meckel’s diverticulum. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:55-56. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Murakami R, Sugizaki K, Kobayashi Y, Ogura J, Yamamoto K, Kurokawa A, Kumazaki T. Strangulation of small bowel due to Meckel diverticulum: CT findings. Clin Imaging. 1999;23:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nath DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent: a case of Meckel’s diverticulum. Minn Med. 2004;87:46-48. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gamblin TC, Glenn J, Herring D, McKinney WB. Bowel obstruction caused by a Meckel’s diverticulum enterolith: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg. 2003;60:63-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prall RT, Bannon MP, Bharucha AE. Meckel’s diverticulum causing intestinal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3426-3427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Freeny PC, Walker JH. Inverted diverticula of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Radiol. 1979;4:57-59. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Levy AD, Hobbs CM. From the archives of the AFIP. Meckel diverticulum: radiologic features with pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:565-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dumper J, Mackenzie S, Mitchell P, Sutherland F, Quan ML, Mew D. Complications of Meckel’s diverticula in adults. Can J Surg. 2006;49:353-357. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Abel R, Keen CE, Bingham JB, Maynard J, Agrawal MR, Ramachandra S. Heterotopic pancreas as lead point in intussusception: new variant of vitellointestinal tract malformation. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kitsuki H, Iwasaki K, Yoshitomi S, Matsuura Y, Natsuaki Y, Torisu M. An adult case of bleeding Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosed by preoperative angiography. Surg Today. 1993;23:926-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kopácová M, Bures J, Vykouril L, Hladík P, Simkovic D, Jon B, Ferko A, Tachecí I, Rejchrt S. Intraoperative enteroscopy: ten years’ experience at a single tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1111-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baldisserotto M, Maffazzoni DR, Dora MD. Sonographic findings of Meckel’s diverticulitis in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:425-428. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Khalife S, Soyer P, Alatawi A, Vahedi K, Hamzi L, Dray X, Placé V, Marteau P, Boudiaf M. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: preliminary comparison of 64-section CT enteroclysis with video capsule endoscopy. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pilleul F, Penigaud M, Milot L, Saurin JC, Chayvialle JA, Valette PJ. Possible small-bowel neoplasms: contrast-enhanced and water-enhanced multidetector CT enteroclysis. Radiology. 2006;241:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Heiss P, Wrede CE, Hamer OW, Mueller-Wille R, Rennert J, Siebig S, Schoelmerich J, Feuerbach S, Zorger N. Multidetector computed tomography mesentericography for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Rofo. 2011;183:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang BL, Fang YH, Chen CX, Li YM, Xiang Z. Single-center experience of 309 consecutive patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5740-5745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, Alexander JA, Fidler JL, Burton SS, McCullough CH. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: evaluation with 64-section multiphase CT enterography--initial experience. Radiology. 2008;246:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Van Weyenberg SJ, Meijerink MR, Jacobs MA, Van der Peet DL, Van Kuijk C, Mulder CJ, Van Waesberghe JH. MR enteroclysis in the diagnosis of small-bowel neoplasms. Radiology. 2010;254:765-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mitchell SH, Schaefer DC, Dubagunta S. A new view of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:875-881. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Narin B, Sungurlu F, Balci A, Arman A, Kurdas OO, Simsek M. Comparison of MR enteroclysis with colonoscopy in Crohn’s disease--first locust bean gum study from Turkey. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Katsinelos P, Chatzimavroudis G, Terzoudis S, Patsis I, Fasoulas K, Katsinelos T, Kokonis G, Zavos C, Vasiliadis T, Kountouras J. Diagnostic yield and clinical impact of capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding during routine clinical practice: a single-center experience. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Scaglione G, Russo F, Franco MR, Sarracco P, Pietrini L, Sorrentini I. Age and video capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study on hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1188-1193. [PubMed] |

| 29. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Neumann M, Ell C. Push-and-pull enteroscopy using the double-balloon technique: method of assessing depth of insertion and training of the enteroscopy technique using the Erlangen Endo-Trainer. Endoscopy. 2005;37:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, Gerson L, Leighton J, Chen A, Schembre D, Chen G, Semrad C, Kamal A, Harrison EM. What is the learning curve associated with double-balloon enteroscopy? Technical details and early experience in 6 U.S. tertiary care centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:740-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Heine GD, Hadithi M, Groenen MJ, Kuipers EJ, Jacobs MA, Mulder CJ. Double-balloon enteroscopy: indications, diagnostic yield, and complications in a series of 275 patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |