Published online Apr 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2412

Revised: February 2, 2013

Accepted: February 28, 2013

Published online: April 21, 2013

Processing time: 111 Days and 1.2 Hours

AIM: To assess the prognostic value of serum human relaxin 2 (H2 RLN) level in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

METHODS: From October 1998 to September 2009, 146 patients with histopathologically confirmed ESCC were enrolled in this study. One hundred patients underwent en bloc esophagectomy, and 46 patients with unresectable tumors underwent palliative surgery. Five of the 146 patients died of surgical complications. Serum levels of H2 RLN were measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. The relationship between serum H2 RLN level and each of the clinicopathological parameters was analyzed using the χ2 test. Patients were classified into two groups according to their H2 RLN level (< 0.462 ng/mL vs≥ 0.462 ng/mL). When any analysis cell had fewer than five cases, the Fisher’s exact test was used. The statistical difference between groups A and B in each clinicopathological category was determined by the Student’s t test (two-tailed) or analysis of variance. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. The statistical difference in survival between the different groups was compared using the log-rank test. Survival correlation with the prognostic factors was further investigated by multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model with backward stepwise likelihood ratio.

RESULTS: ESCC patients tended to have significantly higher serum H2 RLN concentrations (0.48 ± 0.17 ng/mL, n = 141) compared with the healthy control group (0.342 ± 0.12 ng/mL, n = 112). There was a significant difference between patients with lymph node involvement (0.74 ± 0.15 ng/mL, n = 90), distant metastasis (0.90 ± 0.19 ng/mL, n = 32) and those without lymph node involvement (0.45 ± 0.12 ng/mL, n = 51), and distant metastasis (0.43 ± 0.14 ng/mL, n = 109), respectively (P < 0.01). Patients with high H2 RLN levels (≥ 0.462 ng/mL) had a poorer prognosis than patients with low serum H2 RLN levels (< 0.462 ng/mL; P = 0.0056). The H2 RLN level was also correlated with survival and tumor-node-metastasis staging, but not with age, tumor size, gender, lymphovascular invasion or the histological grade of tumors. Cox regression analysis showed that H2 RLN was an independent variable.

CONCLUSION: Serum concentrations of H2 RLN are frequently elevated in ESCC patients and are correlated with disease metastasis and survival. Serum concentrations of H2 RLN may be an important prognostic marker in ESCC patients.

Core tip: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most aggressive carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Despite improvements in detection, surgical resection, and (neo-) adjuvant therapy, the overall survival of ESCC patients remains lower than that of patients with other solid tumors due to distant metastasis. Therefore, it is important to detect disease progression and metastasis as early as possible to improve timely treatment and improve survival. In this study, the authors assessed the prognostic value of serum human relaxin 2 (H2 RLN) level in patients with ESCC, and found that serum concentrations of H2 RLN were elevated in ESCC patients and were correlated with disease metastasis and survival. Serum concentrations of H2 RLN may be an important prognostic marker in ESCC patients.

- Citation: Ren P, Yu ZT, Xiu L, Wang M, Liu HM. Elevated serum levels of human relaxin-2 in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(15): 2412-2418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i15/2412.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2412

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most aggressive carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Despite improvements in detection, surgical resection, and (neo-) adjuvant therapy, the overall survival of ESCC patients remains lower than that of patients with other solid tumors due to distant metastasis[1-4]. Therefore, it is important to detect disease progression and metastasis as early as possible to improve timely treatment and improve survival.

Several recent studies have shown that tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage and the number of diseased lymph nodes are two important factors associated with the prognosis of ESCC[2-4]. Although these two factors can only be assessed during surgery, they are not applicable for monitoring disease advancement and the potential of metastasis. On the other hand, serum biomarkers are often associated with the biological behavior of cancer cells. The prognostic measure of a serum biomarker that can reflect the concerted interaction between the tumor and the host immune system may provide scientific insight to improve the therapeutic strategy. However, there are few serum biomarkers that can be used as complementary prognostic factors for patients with ESCC.

Relaxin (RLN) is a short circulating peptide hormone. Two highly homologous genes on human chromosome 9 encode relaxin gene 1 (RLN1) and relaxin gene 2 (RLN2) peptides with a predicted 82% identity at the amino acid level[5,6]. Despite having two peptide-coding genes, RLN1 and RLN2, the major stored and circulatory form of relaxin in humans is RLN2. RLN2 is produced in the prostate by males[7] and in the corpus lutea in females[8], and RLN1 is a pseudogene, which does not translate into a functional peptide in rodents, humans and other non-human species.

RLN plays an important role in the remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) in several reproductive tract tissues[9]. There is growing evidence that implicates RLN in supporting tumor cell growth and metastasis[10]. RLN is known to regulate the expression of a variety of genes, including collagens and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1[11], vascular endothelial growth factor[9] and cyclooxygenase-2[10]. In addition, the expression and catalytic activities of MMP-1, 2, 3 and 9 are increased by RLN[12,13]. Moreover, RLN regulates the complex interactions of the plasminogen activator and MMPs/tissue inhibitors of MMP systems on the ECM, thus facilitating tumor cell attachment, migration and invasion. RLN has been shown to enhance in vitro invasiveness of breast cancer cells by upregulating the MMP-2, -7, -9, -13 and -14[14]. Similarly, adenovirus-mediated expression of RLN promotes the invasive potential of breast cancer cells[15].

A previous study showed that RLN concentrations in cancer patients were significantly higher than in a control population of healthy blood donors and patients with various other diseases. There was a significant difference between patients with and without metastases. Overall survival was shorter in RLN-positive than in RLN-negative patients. Cox regression analysis showed that RLN was not an independent variable, in contrast to metastatic disease and primary lymph node involvement.

In this study, we measured the serum levels of human relaxin 2 (H2 RLN) in ESCC patients and healthy controls using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and analyzed the association between clinical parameters of ESCC and serum H2 RLN levels.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Cancer Center at Tianjin University.

From October 1998 to October 2009, 146 consecutive patients with histopathologically proven ESCC were enrolled in this study. The average age was 62.7 ± 11.3 years, and the male: female ratio was 40:3 (male 136, female 10). Tumor stage was classified according to the TNM system[16]. Extensive preoperative examinations including esophagoscopy with biopsy, esophagogram, chest radiography, sonograms of abdomen and neck, computed tomography of the chest, and radionuclide bone scanning were performed to determine the need for surgery. Patients with resectable tumor (n = 100) underwent en bloc esophagectomy with locoregional lymphadenectomy through a right thoracotomy, laparotomy with reconstruction using the stomach through a retrosternal route, and cervical esophagogastrostomy. For patients at stage IIb or beyond, concurrent chemoradiotherapy was administered after surgery. Patients with unresectable tumor (n = 46) received chemoradiotherapy after the installation of a feeding jejunostomy or bypass procedure. None of these patients received neoadjuvant therapy. After treatment, all patients were followed regularly. Five patients died of cardiopulmonary or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complications after surgery and were excluded from the prognosis analysis. Serum samples were obtained from each patient at the time of diagnosis. Serum samples from 112 healthy individuals with equivalent age and sex distribution were used as normal controls. The Medical Ethics Committee (Tianjin University) approved the protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from each healthy individual (normal controls). The healthy individuals were negative for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Abdominal and breast (female) ultrasound examination, chest X-ray, routine blood tests, and biochemistry tests were performed for the healthy controls, and the results were within normal ranges. After centrifugation of the peripheral blood, serum samples were stored at -20 °C until assayed.

The serum level of H2 RLN was measured with a commercially available ELISA kit (Santa Cruz, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Briefly, 96-well ELISA microplates were coated overnight with 100 μL H2 RLN antibody (Santa Cruz, Shanghai, China) at a final concentration of 0.25 mg/L in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After washing with PBS/0.05% (w/v) Tween-20 (PBST, pH 7.4), the wells were blocked with blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Then, 100 μL diluted serum samples (at 1:30 dilution) were added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Similarly, 100 μL PBS with 0.04% Tween 80 (PBST), PBST lacking antibody was used as a negative control. Following three washes with PBST, 100 μL antibody diluted to a concentration of 0.25 mg/L was added. After incubation at room temperature for 2 h, 100 μL avidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (at 1:2000 dilution) was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Excess conjugate was removed by washing the plates three times with PBST. The amount of bound conjugate was determined by adding phosphate buffer and 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid. Liquid substrate solution to each well, and plates were incubated at room temperature for color development. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Lab. Inc., Hercules, CA, United States). All analyses were performed in triplicate. The coefficient of variation was lower than 15% between analyses. Concentrations of H2 RLN were presented in ng/mL. Patients were classified into two groups according to their H2 RLN level (< 0.462 ng/mL vs≥ 0.462 ng/mL).

The results were expressed as mean ± SD. The relationship between serum H2 RLN level and each of the clinicopathological parameters (age, size, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, cell differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, and tumor stage) was analyzed using the χ2 test. When any analysis cell had fewer than five cases, Fisher’s exact test was used. The statistical difference between groups A and B in each clinicopathological category was determined by Student’s t test (two-tailed) or analysis of variance. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. The statistical difference in survival between the different groups was compared using the log-rank test. Survival correlation with the prognostic factors was further investigated by multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model with backward stepwise likelihood ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (Chicago, IL, United States). Statistical significance was assumed for P < 0.05.

Serum H2 RLN was 0.342 ± 0.12 ng/mL in normal healthy controls (range, 0.26-0.41 ng/mL; n = 112) and was significantly higher in patients with ESCC (0.48 ± 0.17 ng/mL; range, 0.43-0.58 ng/mL, n = 141; P < 0.05). This was above the normal range in 69.5% (98 of 141) of ESCC patients before surgery, and 30.5% (43 of 141) of these patients had levels < 0.462 ng/mL, the mean plus 1 SD as determined from the control. Using 0.462 ng/mL as the cutoff value, these ESCC patients were then divided into group A (n = 43) as those with the lower level (< 0.462 ng/mL; mean, 0.45 ng/mL; range, 0.164-0.618 ng/mL) and group B (n = 98) as those with the higher level (> 0.462 ng/mL; mean, 0.71 ng/mL; range, 0.624-0.93 ng/mL). Of the 146 ESCC patients, 136 male patients had a serum H2 RLN level ranging from 0.26-0.40 ng/mL and 10 female patients had a serum H2 RLN level ranging from 0.253-0.41 ng/mL. χ2 analysis showed that the preoperative serum H2 RLN levels correlated well with lymph node involvement (N status) and distant metastasis (M status, Table 1). Higher H2 RLN levels were related to disease progression (Table 2). Serum levels of H2 RLN were significantly higher in patients with lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis than in those without lymph node involvement or distant metastasis. No relationship was found between gender and H2 RLN levels. However, although the patients were grouped by their histopathological findings (pathological grade or lymphovascular invasion), no more differences were found in their serum H2 RLN levels (Tables 1 and 2). Although ESCC was most often found in male patients, there were only a limited number of female patients (n = 10), and we were unable to study the correlations between H2 RLN levels and sex hormones (ER, PR and Her-2).

| Clinicopathological factors | Groups1 | P value2 | |

| A (n) | B (n) | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.144 | ||

| < 65 (n = 72) | 21 | 51 | |

| ≥ 65 (n = 69) | 22 | 47 | |

| Tumor status | 0.089 | ||

| T1 (n = 16) | 2 | 14 | |

| T2 (n = 14) | 4 | 10 | |

| T3 (n = 75) | 24 | 51 | |

| T4 (n = 36) | 13 | 23 | |

| Lymph node involvement | 0.003 | ||

| Positive (n = 90) | 32 | 58 | |

| Negative (n = 51) | 11 | 40 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.027 | ||

| Positive (n = 32) | 21 | 11 | |

| Negative (n = 109) | 22 | 87 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.186 | ||

| Positive (n = 42) | 18 | 24 | |

| Negative (n = 99) | 25 | 74 | |

| Stage (TNM) | 0.035 | ||

| I (n = 17) | 7 | 10 | |

| II (n = 37) | 8 | 29 | |

| III (n = 53) | 10 | 43 | |

| IV (n = 34) | 18 | 16 | |

| Cell differentiation | 0.267 | ||

| Well (n = 23) | 9 | 14 | |

| Moderate (n = 90) | 23 | 56 | |

| Poor (n = 28) | 9 | 19 | |

| Category | H2 RLN (ng/mL) | P value |

| Normal control (n = 112) | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.0261 |

| ESCC (n = 141) | 0.48 ± 0.17 | |

| Tumor status | 0.1422 | |

| T1 (n = 16) | 0.32 ± 0.08 | |

| T2 (n = 14) | 0.53 ± 0.13 | |

| T3 (n = 75) | 0.49 ± 0.16 | |

| T4 (n = 36) | 0.47 ± 0.19 | |

| Lymph node involvement | 0.0141 | |

| Positive (n = 90) | 0.74 ± 0.15 | |

| Negative (n = 51) | 0.45 ± 0.12 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.0161 | |

| Positive (n = 32) | 0.90 ± 0.19 | |

| Negative (n = 109) | 0.43 ± 0.14 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.3422 | |

| Positive (n = 42) | 0.51 ± 0.18 | |

| Negative (n = 99) | 0.46 ± 0.16 | |

| Stage (TNM) | 0.0022 | |

| I (n = 17) | 0.42 ± 0.09 | |

| II (n = 37) | 0.46 ± 0.12 | |

| III (n = 53) | 0.47 ± 0.14 | |

| IV (n = 34) | 0.82 ± 0.23 | |

| Cell differentiation | 0.5421 | |

| Well (n = 23) | 0.46 ± 0.21 | |

| Moderate (n = 90) | 0.48 ± 0.13 | |

| Poor (n = 28) | 0.52 ± 0.12 |

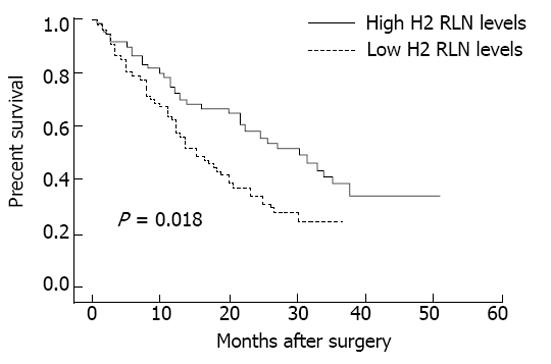

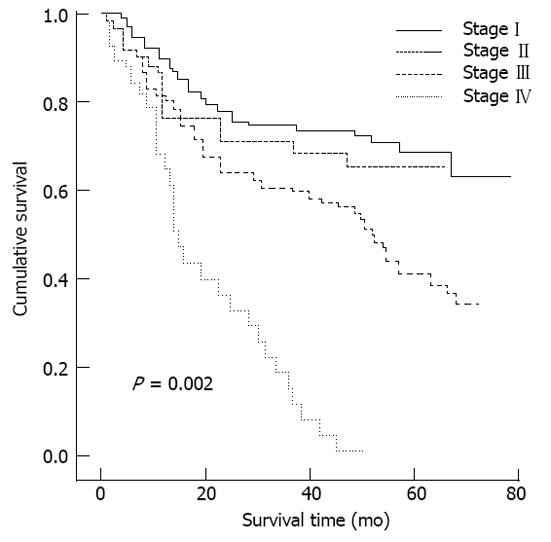

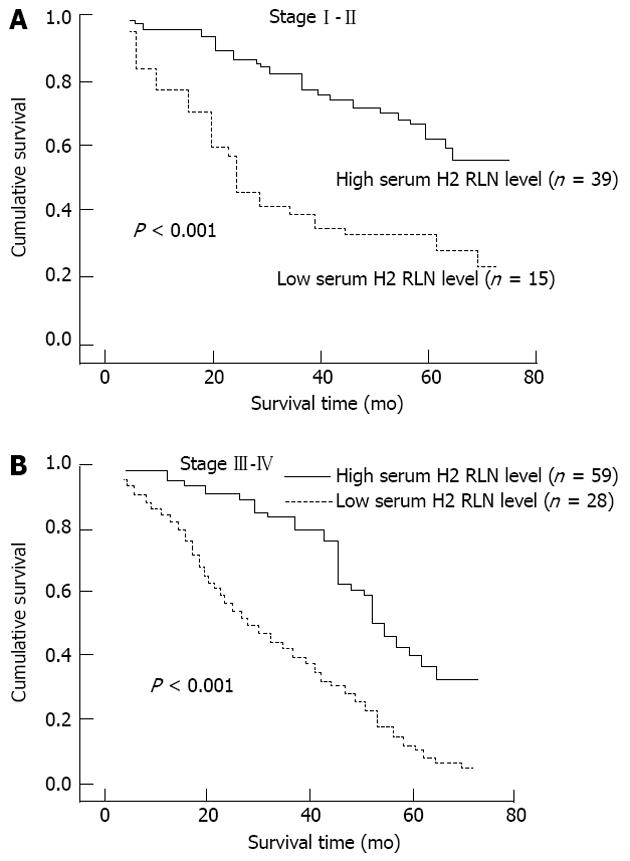

The associations between median serum H2 RLN levels and clinicopathological parameters are presented in Table 2. H2 RLN levels were not associated with age, tumor size and gender (data not shown), cell differentiation, lymphovascular invasion and tumor status, however, elevated median H2 RLN levels were significant for patients with distant metastasis and lymph node involvement (P < 0.05). We also noted that the median levels of H2 RLN significantly increased with increasing T classification (P < 0.05) of the malignancy. Next, patients were classified into two groups according to their H2 RLN level (< 0.462 ng/mL vs≥ 0.462 ng/mL); the relationships between H2 RLN levels and clinicopathological parameters were assessed. No significant difference in age, gender, tumor size (data not shown), tumor status, lymphovascular invasion and cell differentiation was found between the two groups; however, patients with lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis and higher clinical stage were more frequently observed in the elevated H2 RLN group (≥ 0.462 ng/mL) than in the non-elevated H2 RLN group (< 0.462 ng/mL). The overall cumulative survival rates of our patients were 42.4% at 2 years and 18.2% at 5 years. In view of the serum H2 RLN level, group A patients seemed to have a much worse prognosis than group B patients (P = 0.018; Figure 1). Figures 2 and 3 show the comparison of survival time between different disease stages. The cumulative 2-year survival rate for group A patients was 27.3% and for group B patients was 48.2%. The median survival for group A was 7.8 mo, and for group B was 22.4 mo. Among patients who had persistently high H2 RLN levels or a marked increase in H2 RLN level within a short interval (1-6 mo) after esophagectomy, distant metastasis of cancer was frequently found. On the other hand, patients with a low preoperative level of H2 RLN or H2 RLN levels which decreased after esophagectomy could remain disease-free for 12-23 mo. As previously mentioned, the depth of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, distant nodal or organ metastasis correlated well with H2 RLN level.

Further univariate and multivariate analyses also showed these parameters to be independent factors for patient survival (lymph node metastasis, P < 0.001; distant organ metastasis, P < 0.001; H2 RLN, P < 0.05 (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value1 | HR | 95%CI | P value1 | |

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| < 65 vs≥ 65 | 1.321 | 0.864-1.743 | 0.185 | 1.268 | 0.747-1.826 | 0.174 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male vs female | 0.942 | 0.621-1.563 | 0.342 | 0.852 | 0.732-1.472 | 0.296 |

| Lymph node involvement | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 2.136 | 1.142-2.687 | < 0.001 | 2.830 | 1.384-2.982 | 0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 3.784 | 2.543-5.894 | < 0.001 | 3.549 | 1.302-3.108 | 0.001 |

| pTNM | ||||||

| I-II vs III-IV | 3.120 | 2.148-5.143 | < 0.001 | 1.632 | 1.130-2.740 | 0.028 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 1.121 | 0.765-1.574 | 0.129 | 1.290 | 0.862-1.420 | 0.172 |

| H2 RLN level | ||||||

| < 0.462 ng/mL vs≥ 0.462 ng/mL | 2.469 | 1.362-2.836 | 0.015 | 2.530 | 1.424-2.732 | 0.003 |

Identification of targets for early detection of ESCC is important to improve the prognosis of patients with this pernicious disease. Currently, carcinoembryonic antigen[17], cytokeratin-19 fragments[18], and squamous cell carcinoma-associated antigen[18], are routinely used as serum markers for the detection of ESCC. Due to the low sensitivity and specificity of detection of these markers[19], additional serum markers must be established for early detection and diagnosis of ESCC.

It has been previously shown that the polypeptide hormone relaxin is expressed exclusively in human breast cancer[20], and relaxin confers increased carcinoma cell growth, motility, adhesion and in vitro invasiveness in human breast cancer cells[14,21]. Furthermore, adenoviral-mediated delivery of the prorelaxin 2 gene increases the invasiveness of canine breast cancer cells[10]. It was reported that serum RLN concentrations were significantly higher in breast cancer patients than in a control population of healthy blood donors[22]. Notably, serum RLN levels were higher in patients with metastatic disease compared to those without known metastases[22].

Immunostaining with antibodies to human relaxin (H2) suggests the presence of a relaxin-like peptide in the gastrointestinal tract and its tumors[23]. In our preliminary experiment, we found that H2 RLN was overexpressed in ESCC tissues using an immunohistochemistry assay (data not shown). In this study, we evaluated the H2 RLN serum concentrations in ESCC patients. Our results demonstrate that median H2 RLN serum concentrations in a population of ESCC patients were significantly higher than those in a control group of healthy blood donors. H2 RLN concentrations were particularly elevated in patients with lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. However, no significant differences were found in the serum levels of H2 RLN in ESCC patients according to different histological tumor grades, age, tumor size and tumor status. Thus, H2 RLN concentration may be a suitable routine serum marker for the detection of metastatic disease in ESCC. Because our study involved a relatively small number of ESCC patients and the sensitivity and specificity of our assay which measured serum H2 RLN were not sufficiently high, further confirmation of these findings in a larger sample size is warranted.

Evaluation of survival data showed that survival was significantly shorter in patients with H2 RLN concentrations > 0.462 ng/mL, and high H2 RLN concentrations predicted a poor prognosis in patients with ESCC, especially in those presenting with distant and lymph node metastasis. H2 RLN was not an independent variable in ESCC. However, in breast cancer[22], although elevated RLN serum concentrations were a significant discriminator between metastatic and non-metastatic patients, the predictive power of individual RLN values in the investigated population was rather low, as there was a broad overlap of concentrations in the two groups with or without metastases, suggesting cell type-specific effects of RLN.

In conclusion, we found that serum H2 RLN levels were increased in ESCC patients and correlated positively with TNM stage and both lymph node and distant metastasis, but not with gender, tumor size or the histological grade of ESCC. H2 RLN was an independent variable in ESCC. Examining and monitoring serum H2 RLN levels may be useful in estimating the prognosis of patients with ESCC.

We wish to thank both the reviewers and editors for their helpful instructions for our further studies.

Although the serum level of human relaxin-2 (H2 RLN) has been shown to correlate with progression and prognosis of several cancers, data to support its clinical significance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) are limited. This study was conducted to assess the prognostic value of serum human H2 RLN level in patients with ESCC.

Serum levels of H2 RLN were measured by ELISA in 146 patients with histopathologically confirmed ESCC. The authors also assessed the prognostic value of serum human H2 RLN level in these patients with ESCC.

Serum concentrations of H2 RLN are frequently elevated in ESCC patients and are correlated with disease metastasis and survival.

Serum concentrations of H2 RLN may be an important prognostic marker in ESCC patients.

The authors assessed the prognostic value of serum H2 RLN level in patients with ESCC, and found that serum concentrations of H2 RLN were elevated in ESCC patients and were correlated with disease metastasis and survival. This is an interesting report.

P- Reviewers Goan YG, Inamori M S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Vallböhmer D, Brabender J, Metzger R, Hölscher AH. Genetics in the pathogenesis of esophageal cancer: possible predictive and prognostic factors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:S75-S80. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lam AK. Molecular biology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;33:71-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lehrbach DM, Nita ME, Cecconello I. Molecular aspects of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma carcinogenesis. Arq Gastroenterol. 2003;40:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stoner GD, Wang LS, Chen T. Chemoprevention of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;224:337-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fahn HJ, Wang LS, Huang BS, Huang MH, Chien KY. Tumor recurrence in long-term survivors after treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:677-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patil P, Redkar A, Patel SG, Krishnamurthy S, Mistry RC, Deshpande RK, Mittra I, Desai PB. Prognosis of operable squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Relationship with clinicopathologic features and DNA ploidy. Cancer. 1993;72:20-24. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wang LS, Chow KC, Chi KH, Liu CC, Li WY, Chiu JH, Huang MH. Prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: analysis of clinicopathological and biological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1933-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sherwood OD. Relaxin’s physiological roles and other diverse actions. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:205-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bathgate RA, Ivell R, Sanborn BM, Sherwood OD, Summers RJ. International Union of Pharmacology LVII: recommendations for the nomenclature of receptors for relaxin family peptides. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:7-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feng S, Agoulnik IU, Bogatcheva NV, Kamat AA, Kwabi-Addo B, Li R, Ayala G, Ittmann MM, Agoulnik AI. Relaxin promotes prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1695-1702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shabanpoor F, Separovic F, Wade JD. The human insulin superfamily of polypeptide hormones. Vitam Horm. 2009;80:1-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Palejwala S, Tseng L, Wojtczuk A, Weiss G, Goldsmith LT. Relaxin gene and protein expression and its regulation of procollagenase and vascular endothelial growth factor in human endometrial cells. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1743-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silvertown JD, Summerlee AJ, Klonisch T. Relaxin-like peptides in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Unemori EN, Amento EP. Relaxin modulates synthesis and secretion of procollagenase and collagen by human dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10681-10685. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Unemori EN, Lewis M, Grove BH, Deshpande U. Relaxin induces specific alterations in gene expression in human endometrial stromal cells. Proceedings from the Third International Congress on Relaxin and Related Peptides. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher 2002; 65-72. |

| 16. | Qin X, Chua PK, Ohira RH, Bryant-Greenwood GD. An autocrine/paracrine role of human decidual relaxin. II. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1). Biol Reprod. 1997;56:812-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Binder C, Hagemann T, Husen B, Schulz M, Einspanier A. Relaxin enhances in-vitro invasiveness of breast cancer cell lines by up-regulation of matrix metalloproteases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:789-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Silvertown JD, Geddes BJ, Summerlee AJ. Adenovirus-mediated expression of human prorelaxin promotes the invasive potential of canine mammary cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3683-3691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | International Union Against Cancer. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, revised edition. New York: Springer-Verlag 1987; . |

| 20. | Nakashima S, Natsugoe S, Matsumoto M, Miyazono F, Nakajo A, Uchikura K, Tokuda K, Ishigami S, Baba M, Takao S. Clinical significance of circulating tumor cells in blood by molecular detection and tumor markers in esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2003;133:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cao X, Zhang L, Feng GR, Yang J, Wang RY, Li J, Zheng XM, Han YJ. Preoperative Cyfra21-1 and SCC-Ag serum titers predict survival in patients with stage II esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kawaguchi H, Ohno S, Miyazaki M, Hashimoto K, Egashira A, Saeki H, Watanabe M, Sugimachi K. CYFRA 21-1 determination in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: clinical utility for detection of recurrences. Cancer. 2000;89:1413-1417. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Sacchi TB, Bani D, Brandi ML, Falchetti A, Bigazzi M. Relaxin influences growth, differentiation and cell-cell adhesion of human breast-cancer cells in culture. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |