Published online Apr 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2087

Revised: January 28, 2013

Accepted: February 5, 2013

Published online: April 7, 2013

Processing time: 112 Days and 2.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate the features of hepatic paragonimiasis on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) imaging.

METHODS: Fifteen patients with hepatic paragonimiasis who were admitted to our hospital between March 2008 and August 2012 were enrolled to this study. The conventional ultrasound and CEUS examinations were performed with a Philips IU22 scanner with a 1-5-MHz convex transducer. After conventional ultrasound scanning was completed, the CEUS study was performed. Pulse inversion harmonic imaging was used for CEUS. A bolus injection of 2.4 mL of a sulfur hexafluoride-filled microbubble contrast agent (SonoVue) was administered. CEUS features were retrospectively reviewed and correlated with pathological findings.

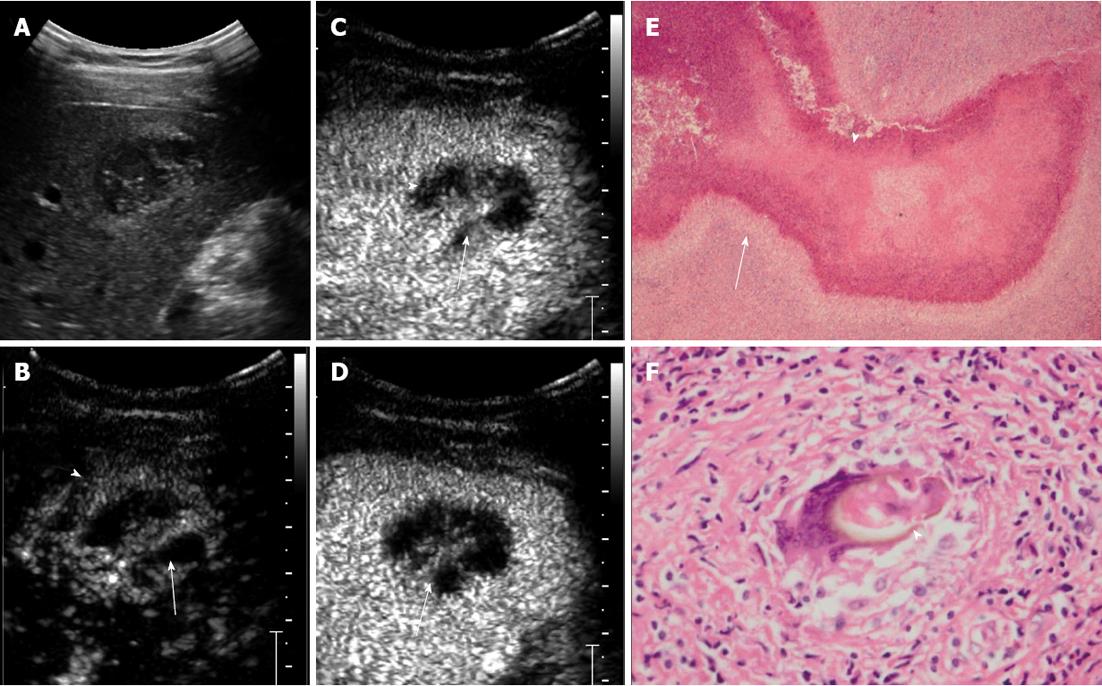

RESULTS: In total, 16 lesions were detected on CEUS. The mean size of the lesions was 4.4 ± 1.6 cm (range, 1.7-6.6 cm). Subcapsular location was found in 12 lesions (75%). All the lesions were hypoechoic. Six lesions (37.5%) were of mixed content, seven (43.8%) were solid with small cystic areas, and the other three (18.8%) were completely solid. Ten lesions (62.5%) were rim enhanced with irregular tract-like nonenhanced internal areas. Transient wedge-shaped hyperenhancement of the surrounding liver parenchyma was seen in seven lesions (43.8%). Areas with hyper- or iso-enhancement in the arterial phase showed contrast wash-out and appeared hypoenhanced in the late phase. The main pathological findings included: (1) coagulative or liquefactive necrosis within the lesion, infiltration of a large number of eosinophils with the formation of chronic eosinophilic abscesses and sporadic distribution of Charcot-Leyden crystals; and (2) hyperplasia of granulomatous and fibrous tissue around the lesion.

CONCLUSION: Subcapsular location, hypoechogenicity, rim enhancement and tract-like nonenhanced areas could be seen as the main CEUS features of hepatic paragonimiasis.

Core tip: We retrospectively investigated the contrast-enhanced sonographic features of hepatic paragonimiasis. Hepatic paragonimiasis has its own features on contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Knowledge of these findings is helpful in differentiating hypoechoic lesions in the liver. When a subcapsular hypoechoic lesion with irregular tract-like non-enhancing necrosis is presented in non-cirrhotic liver, the diagnosis of hepatic paragonimiasis should be suspected.

- Citation: Lu Q, Ling WW, Ma L, Huang ZX, Lu CL, Luo Y. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic findings of hepatic paragonimiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(13): 2087-2091

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i13/2087.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2087

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic infestation caused by the lung fluke. Although the primary site of paragonimiasis is the lungs, ectopic infestation can occur in locations such as the brain, muscles, retroperitoneum, and liver[1-6]. The liver is known to be an organ in which ectopic paragonimiasis may occur. Hepatic paragonimiasis often appears as a mass that should be differentiated from other cancerous lesions. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has been widely used in characterization of focal liver lesions (FLLs)[7-14]. The enhancement patterns of several FLLs have been described and are well known[7,15-17]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the CEUS features of hepatic paragonimiasis have not been investigated or reported in the English-language literature. In this study, we retrospectively investigated the CEUS features of hepatic paragonimiasis.

We retrospectively reviewed the results of conventional and CEUS examination of 15 patients with hepatic paragonimiasis who were admitted to our hospital between March 2008 and August 2012. There were eight men and seven women with a mean age of 42.5 ± 12.3 years (range, 29-65 years). All patients in this study were residents of China’s Sichuan Province, which is an endemic area of paragonimiasis, especially the paragonimiasis skrjabini variety, and a majority of them (10/15) had a history of eating crayfish. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the hospital. All the patients underwent surgery and the diagnoses were confirmed histologically.

The conventional ultrasound and CEUS examinations were performed with a Philips IU22 scanner (Philips Medical Solutions; Mountain View, CA, United States) with a 1-5-MHz convex transducer. The CEUS imaging technique used in this study was pulse inversion harmonic imaging. The mechanical index for CEUS was 0.06. After conventional ultrasound scanning was completed, the CEUS study was performed. A bolus injection of 2.4 mL sulfur hexafluoride-filled microbubble contrast agent (SonoVue; Bracco SpA, Milan, Italy) was administered through a 20-gauge needle placed in the antecubital vein. A flush of 5 mL 0.9% sodium chloride solution was followed after the injection of SonoVue. On completion of the SonoVue injection, the timer was started simultaneously. The target lesion and surrounding liver parenchyma were observed continuously for 6 min. As previously described by Albrecht et al[18], the arterial phase was defined as 7-30 s after contrast agent injection; the portal phase was 31-120 s after injection; and the late phase was 121-360 s after injection. The entire CEUS examination was stored as a dynamic digital video file on the hard disk of the ultrasound system and recorded on a digital video recorder. All of the procedures were performed by Lu Q or Luo Y who had > 5 years of experience of CEUS study of the liver.

The diameters and echogenicity of the tumors on conventional ultrasound were recorded. The enhancing pattern and enhancement level in different phases of CEUS imaging of the lesion were reviewed. The degree of enhancement was divided into nonenhancement, hypoenhancement, isoenhancement, and hyperenhancement according to the enhancement level of the lesion compared with that of the surrounding normal liver parenchyma. Contrast enhancement patterns were classified as homogeneous, heterogeneous, and rim enhancement.

In total, 16 lesions were detected on CEUS. The mean size of the lesions was 4.4 ± 1.6 cm (range: 1.7-6.6 cm). Subcapsular location was found in 12 lesions (75%). All the lesions were hypoechoic. Six lesions (37.5%) were of mixed content, seven (43.8%) were solid with small cystic areas, and the other three (18.8%) were completely solid. Ten lesions (62.5%) were rim enhanced with irregular tract-like nonenhanced internal areas (Figure 1). Transient wedge-shaped hyperenhancement of the surrounding liver parenchyma was seen in seven lesions (43.8%). Areas with hyperenhancement or isoenhancement in the arterial phase showed contrast wash-out and appeared hypoenhanced in the late phase.

Microscopy revealed that there was an egg present in one case, but no larvae were present in any of the lesions. There were areas of track-like or sinus structures. The main pathological findings included: (1) coagulative or liquefactive necrosis within the lesion, infiltration of a large number of eosinophils with the formation of chronic eosinophilic abscesses and sporadic distribution of Charcot-Leyden crystals; and (2) hyperplasia of granulomatous and fibrous tissue around the lesion.

Hepatic paragonimiasis is an infestation caused by ingestion of raw or incompletely cooked freshwater crabs or crayfish infected with metacercariae. Only two species pathogenic to humans exist in Sichuan Province, namely, Paragonimus skrjabini and Paragonimus westermani[19]. During the journey from the intestine to the lung where juvenile worms mature, the juvenile worms often cause damage to the liver capsule and parenchyma[20,21]. Definitive diagnosis of paragonimiasis is based on the presence of eggs in patients’ sputum or feces, or flukes in histological specimens. Polypide and eggs usually cannot be found in most of the lesions. However, with the epidemiological information, diagnosis can be made histopathologically[22].

The lesion is often incidentally detected by ultrasonography in routine examination. Accurate diagnosis of suspected FLLs is important to determine the most effective therapy. If hepatic infection is correctly diagnosed, the need for surgery can be reduced or even avoided, compared with other abnormalities such as malignant tumors[12,23].

Like other inflammatory lesions, hepatic paragonimiasis typically shows heterogeneous hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and hypoenhancement in the late phase on CEUS. Pathologically, the imaging feature of these lesions was eosinophilic abscesses, in which the enhanced septa in mixed-content lesions and enhanced area in solid lesions represented hyperplasia of granulomatous and fibrous tissue, whereas the unenhanced area represented necrotic debris, and Charcot-Leyden crystals.

The preponderance of subcapsular involvement and tract-like necrosis is characteristic and it may be attributed to the penetrating behavior of juvenile worms and eosinophilic abscess. The wedge-shaped enhancement in adjacent parenchyma in the arterial phase was similar to that reported by Kim et al[5], and can be explained as inflammatory congestion adjacent to eosinophilic abscess[19].

When a hypoechoic lesion in the liver is encountered by sonographic imaging, the differential diagnoses should include hepatocellular carcinoma, pyogenic abscesses, and hemangioma. In hepatocellular carcinoma, the hepatic parenchyma is more likely to be cirrhotic[24]. Necrosis is readily visible by CEUS and is less common in small hepatocellular carcinoma. In pyogenic abscess, fever and pain in the right upper abdomen are more frequent[12]. On CEUS, nonenhancing abscess and enhancing septa are often seen in pyogenic abscess, and lobulated abscess coalesces into a larger abscess cavity, whereas the eosinophilic abscess of hepatic paragonimiasis is irregular and arranged in tract-like fashion. Hepatic hemangioma may present as a hypoechoic lesion, whereas the CEUS manifestations typically show peripheral nodular enhancement in the arterial phase and gradual filling in the portal phase and hyperenhancement in late phase.

In our review of the literature, besides the imaging findings, blood eosinophilia was often seen in hepatic paragonimiasis patients, which was suggestive of parasitic infection[21]. For patients with symptoms of acute infection, praziquantel is the drug of choice to treat paragonimiasis, whereas partial liver resection is more suitable for those who have localized lesions without acute infection symptoms[25,26].

The main limitation of this study was the small number of patients presented. Although hepatic paragonimiasis is rare, further investigation is mandatory.

In conclusion, hepatic paragonimiasis has its own features at CEUS. Thus, knowledge of these findings is helpful in differentiating hypoechoic lesions found in the liver. When a subcapsular hypoechoic lesion with irregular tract-like nonenhancing necrosis is present in noncirrhotic liver, diagnosis of hepatic paragonimiasis should be suspected.

Hepatic paragonimiasis is rare, but it often appears as a mass that should be differentiated from other cancerous lesions. Accurate diagnosis of suspected focal liver lesions (FLLs) is important to determine the most effective therapy. For hepatic infection, the need for surgery can be reduced or even avoided if it is correctly diagnosed, as compared with other abnormalities such as malignant tumors. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) features of hepatic paragonimiasis.

CEUS has been widely used in characterization of FLLs. The enhancement patterns of several FLLs have been described and are well known. However, the CEUS features of hepatic paragonimiasis have not been investigated or reported in the English-language literature.

The CEUS feature of hepatic paragonimiasis has been reported in this study. When a subcapsular hypoechoic lesion with irregular tract-like nonenhancing necrosis is present in noncirrhotic liver, a diagnosis of hepatic paragonimiasis should be suspected.

CEUS is a convenient and useful method for the detection and discrimination of hepatic paragonimiasis. Hepatic paragonimiasis could be better managed if ultrasound technicians and physicians are familiar with its features on CEUS.

CEUS is the application of ultrasound contrast medium to traditional medical sonography. Microbubble contrast agents produce a unique sonogram with increased contrast due to the high echogenicity difference. CEUS can be used to image blood perfusion in organs.

The authors described the CEUS findings of hepatic paragonimiasis. They analyzed 16 lesions of hepatic paragonimiasis, and demonstrated several specific findings. The article is well organized and well written.

P- Reviewer Miki K S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Cha SH, Chang KH, Cho SY, Han MH, Kong Y, Suh DC, Choi CG, Kang HK, Kim MS. Cerebral paragonimiasis in early active stage: CT and MR features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:141-145. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Abdel Razek AA, Watcharakorn A, Castillo M. Parasitic diseases of the central nervous system. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21:815-841, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Miyazaki I, Hirose H. Immature lung flukes first found in the muscle of the wild boar in Japan. J Parasitol. 1976;62:836-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jeong MG, Yu JS, Kim KW, Kim JK, Kim SJ, Kim HJ, Choi YD. Retroperitoneal paragonimiasis: a case of ectopic paragonimiasis presenting as periureteral masses. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:696-698. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kim EA, Juhng SK, Kim HW, Kim GD, Lee YW, Cho HJ, Won JJ. Imaging findings of hepatic paragonimiasis : a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:759-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park CW, Chung WJ, Kwon YL, Kim YJ, Kim ES, Jang BK, Park KS, Cho KB, Hwang JS, Kwon JH. Consecutive extrapulmonary paragonimiasis involving liver and colon. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:186-189. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Claudon M, Cosgrove D, Albrecht T, Bolondi L, Bosio M, Calliada F, Correas JM, Darge K, Dietrich C, D’Onofrio M. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) - update 2008. Ultraschall Med. 2008;29:28-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bryant TH, Blomley MJ, Albrecht T, Sidhu PS, Leen EL, Basilico R, Pilcher JM, Bushby LH, Hoffmann CW, Harvey CJ. Improved characterization of liver lesions with liver-phase uptake of liver-specific microbubbles: prospective multicenter study. Radiology. 2004;232:799-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bartolotta TV, Taibbi A, Galia M, Runza G, Matranga D, Midiri M, Lagalla R. Characterization of hypoechoic focal hepatic lesions in patients with fatty liver: diagnostic performance and confidence of contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:650-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dietrich CF, Mertens JC, Braden B, Schuessler G, Ott M, Ignee A. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of histologically proven liver hemangiomas. Hepatology. 2007;45:1139-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Celik H, Ozdemir H, Yücel C, Gultekin S, Oktar SO, Arac M. Characterization of hyperechoic focal liver lesions: quantitative evaluation with pulse inversion harmonic imaging in the late phase of levovist. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:39-47. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Liu GJ, Lu MD, Xie XY, Xu HX, Xu ZF, Zheng YL, Liang JY, Wang W. Real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of infected focal liver lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:657-666. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Morin SH, Lim AK, Cobbold JF, Taylor-Robinson SD. Use of second generation contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the assessment of focal liver lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5963-5970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lu Q, Luo Y, Yuan CX, Zeng Y, Wu H, Lei Z, Zhong Y, Fan YT, Wang HH, Luo Y. Value of contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasound for cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a report of 20 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4005-4010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Furlan A, Marin D, Cabassa P, Taibbi A, Brunelli E, Agnello F, Lagalla R, Brancatelli G. Enhancement pattern of small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at contrast-enhanced US (CEUS), MDCT, and MRI: intermodality agreement and comparison of diagnostic sensitivity between 2005 and 2010 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2099-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Catala V, Nicolau C, Vilana R, Pages M, Bianchi L, Sanchez M, Bru C. Characterization of focal liver lesions: comparative study of contrast-enhanced ultrasound versus spiral computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1066-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ding H, Wang WP, Huang BJ, Wei RX, He NA, Qi Q, Li CL. Imaging of focal liver lesions: low-mechanical-index real-time ultrasonography with SonoVue. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:285-297. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Albrecht T, Blomley M, Bolondi L, Claudon M, Correas JM, Cosgrove D, Greiner L, Jäger K, Jong ND, Leen E. Guidelines for the use of contrast agents in ultrasound. January 2004. Ultraschall Med. 2004;25:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hu X, Feng R, Zheng Z, Liang J, Wang H, Lu J. Hepatic damage in experimental and clinical paragonimiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:1148-1155. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Yokogawa M. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis. Adv Parasitol. 1965;3:99-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li XM, Yu JQ, Yang ZG, Chu ZG, Peng LQ, Kushwaha S. Correlations between MDCT features and clinicopathological findings of hepatic paragonimiasis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e421-e425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meng YH, Li WH, Zhang SG. Pathological findings in eight cases of paragonimiasis with visceral damage. Zhonghua Binglixue Zazhi. 1995;24:108. |

| 23. | Yoon KH, Ha HK, Lee JS, Suh JH, Kim MH, Kim PN, Lee MG, Yun KJ, Choi SC, Nah YH. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: CT-histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1999;211:373-379. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6572] [Article Influence: 469.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1990;28 Suppl:79-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Johnson RJ, Jong EC, Dunning SB, Carberry WL, Minshew BH. Paragonimiasis: diagnosis and the use of praziquantel in treatment. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:200-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |