Published online Feb 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i6.551

Revised: February 1, 2011

Accepted: February 8, 2011

Published online: February 14, 2012

AIM: To describe a modified technique for placement of a tracheobronchial self-expanding plastic stent (SEPS) in patients with benign refractory hypopharyngeal strictures in order to improve dysphagia and allow stricture remodeling.

METHODS: A case series of four consecutive patients with complex hypopharyngeal strictures after combined therapy for laryngeal cancer, previously submitted to multiple sessions of dilation without lasting improvement, is presented. All patients underwent placement of a small diameter and unflared tracheobronchial SEPS. Main outcome measurements were improvement of dysphagia and avoiding of repeated dilation.

RESULTS: The modified introducer system allowed an easy and technically successful deployment of the tracheobronchial Polyflex stent through the stricture. All four patients developed complications related to stent placement. Two patients had stent migration (one proximal and one distal), two patients developed phanryngocutaneous fistulas and all patients with stents in situ for more than 8 wk had hyperplastic tissue growth at the upper end of the stent. Stricture recurrence was observed at 4 wk follow-up after stent removal in all patients

CONCLUSION: Although technically feasible, placement of a tracheobronchial SEPS is associated with a high risk of complications. Small diameter stents must be kept in place for longer than 3 mo to allow adequate time for stricture remodeling.

- Citation: Silva RA, Mesquita N, Nunes PP, Cardoso E, Pinto RM, Dias LM. Tracheobronchial Polyflex stents for the management of benign refractory hypopharyngeal strictures. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(6): 551-556

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i6/551.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i6.551

Total laryngectomy or pharyngolaryngectomy combined with postoperative radiation therapy is the standard treatment for advanced laryngeal cancer. After therapy, the majority of patients will develop some degree of swallowing dysfunction because of the altered swallowing dynamics of the neopharynx[1]. Differential diagnosis between functional dysphagia, benign strictures and newly developing tumors is essential because of the different therapeutic approach and prognosis. Moreover, late onset dysphagia, usually due to hypopharyngeal or upper esophageal strictures, may occur in up to 58% of patients and can become a devastating complication compromising nutritional status and deteriorating quality of life[2]. These strictures are typically complex with an angulated, irregular and severely narrowed lumen that results from mucosal scarring (healing by secondary intention) after radiation induced mucositis and ischemia[3]. Although they can usually be dilated with bougies, most are difficult to treat and cannot be dilated to an adequate diameter for relief of dysphagia despite repeated sessions or tend to require multiple dilations due to recurrence of dysphagia. Furthermore, deployment of a self-expanding metal or plastic stent is not easy because they are placed very high in the pharynx with the upper flange of the stent at less than 12 cm from the dental arcade. Thereby, nutrition through feeding tubes, nasogastric or percutaneous gastrostomy, is often required.

We developed a modified introducer system for placement of a tracheobronchial self-expanding plastic stent (SEPS) (Polyflex™, Willy Rüsch GmbH/Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA, United States) in patients with refractory and complex hypopharyngeal strictures after surgery and radiotherapy. The purpose was to alleviate dysphagia as well as to allow for hypopharynx conditioning, resulting in a less stenotic lumen. This report describes the technical aspects of the modified introducer system and evaluates the safety and efficacy of this stent in this group of patients.

Four patients with refractory hypopharyngeal strictures after total laryngectomy followed by radiation therapy for laryngeal cancer were included. Before stent placement, all patients had been submitted to several sessions of dilations with Savary-Gilliard polyvinyl bougies over a spring-tip stainless steel guidewire (Cook Medical) or a 0.038 in × 260 cm Jagwire (Boston Scientific) under fluoroscopic guidance. Because of the rigidity of the stricture, it was not possible to introduce dilators larger than 12.8-15 mm even with sessions performed every 2 to 3 wk. Successive recurrence of the stricture was observed in all patients, with consequent dysphagia to semisolid foods. Each patient signed an informed consent form before the endoscopic procedure.

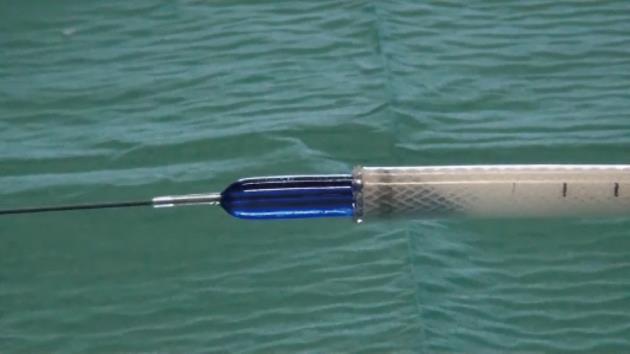

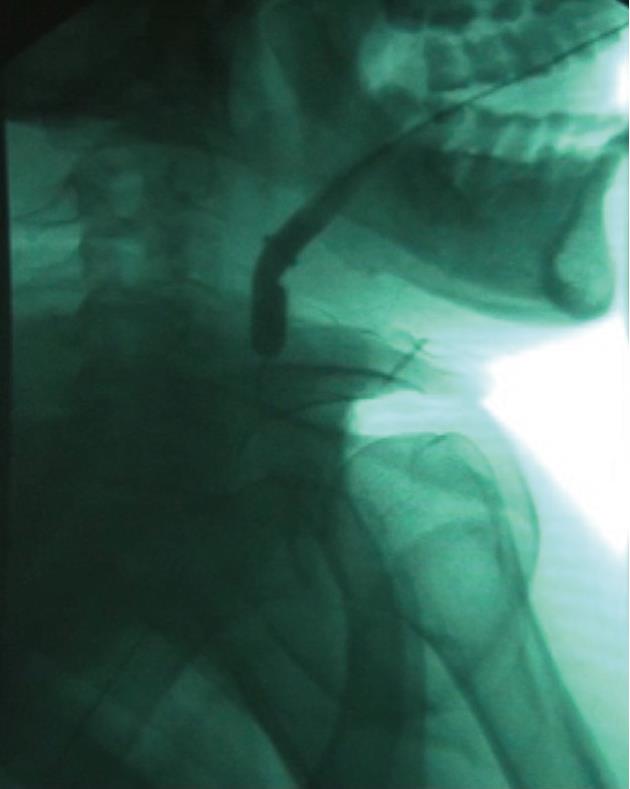

The tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stent used in this study is a SEPS made of silicone with a polyester mesh. While this mesh structure on the outer surface reduces dislocation risk, the silicone coating throughout the stent prevents ingrowth of granulation tissue. The latter, along with the reduction of its cross-section when stretched lengthwise, would have the advantage of allowing easy removal or change of the stent without the usual difficulty associated with self-expanding metal stents. The stent is impregnated with markers at both ends to assist fluoroscopic visualization and endoscopic placement. Since strictures were very narrow and non-compliant and stents would be positioned very high in the hypopharynx, we used a tracheobronchial stent because this was the only available stent of small diameter and without flared ends. However, the Polyflex™ airway stent delivery system, unlike the esophageal one, is somewhat inflexible and stiff and has a blunt edge, making it difficult to transverse the angulation of the oropharynx and to position it through the area of stenosis. To overcome this difficulty we modified the introducer system, cutting both the basket of the stent loader and the opposite end and making the system hollow. An 8-10 mm controlled radial expansion (CRE) balloon dilation catheter (Boston Scientific) without the guidewire was then inserted through the delivery system with the tip protruding from the introducer by 2 to 3 cm and then inflated, resulting in a tapered edge with only a small indentation between the balloon and the delivery tube (Figure 1). The system was then threaded over a 0.035 in × 450 cm Jagwire (Boston Scientific) previously placed under fluoroscopy through the stricture into the esophagus, allowing easy and atraumatic passage and positioning of the stent delivery system (Figure 2). Subsequent stent deployment was performed under simultaneous fluoroscopic guidance and direct vision, with an ultra-thin videoendoscope passed alongside the introducer shaft.

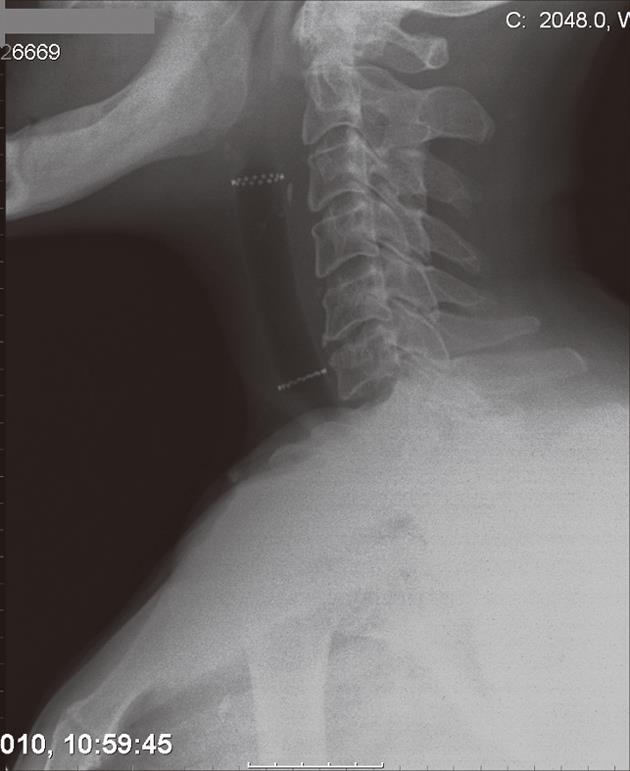

A 71-year-old man with T3N0M0 laryngeal cancer underwent total laryngectomy followed by chemoradiation therapy 2 years previously. Three months after completing therapy, the patient developed dysphagia with solids which progressively worsened. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a 4 cm regular stricture with a 4 mm lumen at 12 cm from the incisors. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed. The patient underwent 8 sessions of dilation for 6 mo with little improvement. At the time of tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stent placement, lumen dilation was performed from 7 to 11 mm, and a 14 mm × 6 cm stent was deployed (Figure 3). There was improvement in the dysphagia score and the patient was able to take solid meals until 2 mo later when he complained of recurrent symptoms. Endoscopy showed 1 cm distal stent migration with tissue overgrowth at the proximal end. Repositioning of the stent into the stricture was performed using an alligator jaw grasping forceps, with resolution of symptoms. However, 6 wk later the patient was readmitted with dysphagia for liquids due to complete obstruction of the upper end of the stent with granulomatous tissue. The stent was removed and no other treatment was performed since the gastroscope could easily be introduced into the stomach. Nevertheless, dysphagia relapsed after 1 mo, with recurrence of the stricture, requiring multiple sessions of dilation during the 5 mo follow-up.

A 54-year-old man with T4N1M0 laryngeal cancer underwent total laryngectomy followed by radiation therapy 7 years previously. Progressive dysphagia occurred 4 years later. Endoscopy revealed a 3 cm regular stricture with a 3 mm lumen at 10 cm from the dental arcade. The patient underwent 3 endoscopic dilations over 2 mo to 12.8 mm, with symptom relief. However, dysphagia relapsed 2 years later and endoscopic bougienage was restarted with dilations performed every 3-4 wk for 10 mo. At this time, it was still not possible to introduce a Savary-Gilliard dilator larger than 12.8 mm, and a 14 mm × 4 cm tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stent was successfully placed across the stricture. Two days after the procedure and subsequent to a coughing attack, the patient developed sudden total dysphagia. Endoscopic examination showed proximal stent migration with impaction in the oropharynx. The stent was therefore removed and replaced by a same diameter but 2 cm longer Polyflex™ stent (Figure 4). The patient was able to tolerate a solid diet until 3 mo later when he complained of only being able to swallow liquids. Hyperplastic tissue growth with stricture formation at the upper end of the stent was observed. After dilation with a 13.5 mm CRE balloon catheter, we used a two-channel therapeutic scope and two alligator jaw forceps grasping at opposite sites to remove the plastic stent. At 4 wk post-procedure the patient had relapse of the stricture and additional dilations were required during the 3 mo follow-up to maintain lumen patency and oral feeding.

A 44-year-old man with T3N2M0 laryngeal cancer who had been treated with total laryngectomy followed by chemoradiation therapy developed progressive dysphagia 2 years after completion of the treatment. Endoscopy revealed a 2 cm long stricture with a 3 mm lumen at 13 cm from the incisors, and dilations were carried out monthly (7 sessions). Despite the stricture allowed passage of a 15 mm dilator, there was only brief relief of the dysphagia due to the inability to maintain lumen diameter. In view of the recurrence of the stricture, a 16 mm × 4 cm tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stent was deployed. There was improvement in the dysphagia score and the patient was able to take solid meals. In the meantime, cervico-thoracic computed tomography demonstrated a large pulmonary mass suspected to be a second primary tumor, and chemotherapy was started. Two months after stent placement, though the patient had no dysphagia, he was readmitted with a pharyngocutaneous fistula with purulent drainage at the level of the lower end of the stent (Figure 5). Intravenous antibiotic therapy was started and the stent removed and replaced 3 d later with a same diameter but 2 cm longer Polyflex™ stent, so that it could occlude the fistula orifice. Although cicatrization was observed within 2 wk, reopening after each course of chemotherapy was necessary. Two months later the patient noted recurrence of dysphagia complicated by the constant leakage of saliva, ingested food and liquids through the fistula. After removal of the stent, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for nutritional support. Even though the patient was given nothing per os for 2 wk, this was not successful in closing the fistula and ultimately a partially covered self-expanding metal stent was used to seal the leakage.

A 56-year-old man with a T3N3M0 carcinoma of the supraglottic larynx was treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by total laryngectomy and radiation therapy. Four months later the patient was referred to our unit with food impaction. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a tight 3 cm long stricture at 13 cm from the incisors. Four sessions of dilation at 3 wk intervals offered only a slight improvement and so a decision was made to introduce a 14 mm × 6 cm tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stent. However, 24 h after the procedure and despite a normal water-soluble contrast swallow, the patient complained of total dysphagia with pharyngo-nasal regurgitation. The stent was therefore removed and the patient discharged. One week later, the patient was readmitted with fever, productive cough and a pharyngocutaneous fistula with purulent drainage. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics and percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement, with resolution of the respiratory symptoms and spontaneous closure of the fistula track 6 wk later.

Hypopharyngeal stricture is a serious complication that may occur after total laryngectomy and radiotherapy. Contributing factors include continued alcohol and tobacco abuse, the dose-volume relationship of the radiotherapy, and normal tissue damage from the tumor and the treatment[4]. Endoscopic dilation is the mainstay of treatment for hypopharyngeal strictures. However, these strictures are usually complex, and even complete lumen obliteration requiring a transgastric endoscopic retrograde approach has been previously reported[5]. When strictures fail to respond to endoscopic dilations, they are defined as refractory. In addition to providing significant physical discomfort, ongoing dilation therapy in these patients carries a risk of perforation and mortality as high as 5% has been reported[6]. Although the use of intralesional steroid injection and electrocautery incisions have been considered for peptic and anastomotic strictures, respectively, no significant benefit has been established for this indication[7,8].

The use of self-expanding stents is another possibility to achieve tissue remodeling needed to promote longer lasting stricture resolution. The rationale is to offer a continuous and stable dilation that might prevent the scarring process and avoid the adhesion of damaged areas. Self-expanding metal stents are currently considered the most effective and widely used method of palliation of malignant dysphagia. However, several limitations preclude their routine use in the management of benign esophageal strictures. Actually, these stents can become embedded into the granulation tissue ingrowth through the mesh of the uncovered part of the stent, resulting in recurrent obstruction and difficult removal. To overcome these disadvantages, a SEPS Polyflex™, designed to induce less tissue ingrowth and to be easily removed, was developed by Boston Scientific Corporation and has been commercially available since 2003. This stent is made of a polyester mesh completely covered by a silicone layer with a smooth inner surface and a structured outer surface. Initial studies on the use of Polyflex™ stents in benign refractory strictures were favorable, with improvement of symptoms and few complications. Repici et al[9] reported 15 patients with caustic, post-radiation, anastomotic and peptic strictures. Stent placement was successful in all patients and long-term resolution of dysphagia after 23 mo follow-up was achieved in 80% of patients. Evrard et al[10] reported 21 patients, of whom 17 had hyperplastic (after metallic stent placement), caustic, peptic, anastomotic and post-radiation strictures, with 81% of patients remaining dysphagia-free during a mean follow-up of 21 mo. However, less encouraging results have since been reported, with a lower success rate and a high incidence of complications. Overall, for benign esophageal strictures, the success rates of SEPSs in the published literature range from 17% to 95%, with 6% being major complications[11].

In the current literature, there are only two small series evaluating the efficacy and safety of stents in the treatment of benign refractory hypopharyngeal strictures. Conio et al[12] developed a modified fully covered self-expanding Niti-S stent with a body diameter of 10 mm, 12 mm or 14 mm and a flared 2 mm wider upper end. Although it effectively improved dysphagia in all patients, six of the seven patients developed complications requiring stent exchange 3 mo after previous stent placement. Due to the stricture recurrence observed after stent removal, prolonged stent placement with periodic stent exchange was necessary. Somani et al[13] described four patients who underwent temporary esophageal Polyflex™ stenting for 3 mo. Although three of the four patients remained symptom-free after a median follow-up of 14 mo, they were able to pre-dilate the strictures up to 15 mm to allow the passage of the stiff 13 mm introducer system and the deployment of a 20 mm body with 23 mm flare plastic stent. While the use of such a large stent can explain the good results, that would not be possible in the tight and rigid strictures observed either in the first study or in our group of patients.

In the present study, the modified introducer system for placement of tracheobronchial Polyflex™ stents allowed an easy and technically successful deployment of the stent through the stricture. The use of small diameter and unflared upper end stents can explain the absence of significant pain or a foreign body sensation in the throat. Nevertheless, all patients developed complications as stent migration, a pharyngocutaneous fistula, and hyperplastic tissue growth with stent obstruction. Actually, although migration is likely to occur with this type of stent, they may be easily recovered or repositioned with an alligator jaw forceps. Moreover, the features of these stents reduce the risk of intestinal complications that may occur after migration of larger or flared stents. Fistula formation can also occur spontaneously after chemoradiation for head and neck cancer, or be precipitated by concurrent chemotherapy or infection. However, there is little doubt that in these patients the high radial expansive force and relative inflexibility of the Polyflex™ stent could have played an important role in the development of the pharyngocutaneous fistulas. Hyperplastic tissue growth with fibrous stricture formation at the upper end of the stent was observed in all patients who had their stents in situ for more than 8 wk, requiring stent removal. This has been previously reported to occur with the Polyflex™ stent in only a small number of patients in the literature and may be related to the stimulation of the underlying pathologic process by the upper edge of the stent, with ongoing obliterative endarteritis and ischemia after radiation injury[14]. Finally, stricture recurrence with dysphagia was observed in all patients at 4 wk follow-up after stent removal indicating that, in strictures with this etiology, small diameter stents must be kept in place for longer than 3 mo to allow adequate time for stricture remodeling.

In conclusion, these results suggest that Polyflex™ stents have limited efficacy in benign hypopharyngeal stricture resolution. New smaller diameter stents are needed to manage these narrow and non-compliant refractory strictures and to provide an alternative approach to continued serial dilation and feeding tube nutrition.

The management of patients who have benign refractory hypopharyngeal strictures after surgery combined with chemoradiation therapy is often unsatisfactory and disappointing. Repeated dilation therapy or long-term feeding through a nasogastric tube or percutaneous gastrostomy is frequently required.

The authors aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a tracheobronchial self-expanding plastic stent (SEPS) (Polyflex™) placed with modified technique in the treatment of refractory hypopharyngeal strictures after combined therapy for laryngeal cancer.

This case series has shown the technical feasibility of tracheobronchial Polyflex stent insertion for hypopharyngeal strictures. The modification of the stiff delivery system, with insertion of a balloon dilation catheter through the introducer resulting in a wire-guided tapered edge, allowed an easy and atraumatic transverse of the oropharynx and stricture. However, the results suggest that these stents have limited efficacy in stricture remodeling and have a high incidence of side effects.

Placement of SEPSs is associated with early hyperplastic tissue growth requiring short term stent replacement. New smaller diameter stents are needed to manage these narrow and refractory hypopharyngeal strictures.

Although the use of temporary SEPS is a well recognized option for treatment of refractory stenosis of gastrointestinal tract, both benign or malignant, this report is interesting because it describes a personal modification of the introducer that should be effectively used for some more complex strictures.

Peer reviewers: Josep M Bordas, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Clinic Institution, Barcelona 08022, Spain; Giovanni D De Palma, Professor, Department of Surgery and Advanced Technologies, University of Naples Federico II, School of Medicine, Naples 80131, Italy

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Murphy BA, Gilbert J. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiation: assessment, sequelae, and rehabilitation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:35-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kronenberger MB, Meyers AD. Dysphagia following head and neck cancer surgery. Dysphagia. 1994;9:236-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sullivan CA, Jaklitsch MT, Haddad R, Goguen LA, Gagne A, Wirth LJ, Posner MR, Tishler RB, Norris CM. Endoscopic management of hypopharyngeal stenosis after organ sparing therapy for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1924-1931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vu KN, Day TA, Gillespie MB, Martin-Harris B, Sinha D, Stuart RK, Sharma AK. Proximal esophageal stenosis in head and neck cancer patients after total laryngectomy and radiation. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Twisk JJ, Brummer RJ, Manni JJ. Retrograde approach to pharyngo-esophageal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:296-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Laurell G, Kraepelien T, Mavroidis P, Lind BK, Fernberg JO, Beckman M, Lind MG. Stricture of the proximal esophagus in head and neck carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:1693-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hordijk ML, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, Kuipers EJ. Electrocautery therapy for refractory anastomotic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramage JI, Rumalla A, Baron TH, Pochron NL, Zinsmeister AR, Murray JA, Norton ID, Diehl N, Romero Y. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection therapy for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2419-2425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Repici A, Conio M, De Angelis C, Battaglia E, Musso A, Pellicano R, Goss M, Venezia G, Rizzetto M, Saracco G. Temporary placement of an expandable polyester silicone-covered stent for treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Evrard S, Le Moine O, Lazaraki G, Dormann A, El Nakadi I, Devière J. Self-expanding plastic stents for benign esophageal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:894-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharma P, Kozarek R. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malignant diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:258-73; quiz 274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Conio M, Blanchi S, Filiberti R, Repici A, Barbieri M, Bilardi C, Siersema PD. A modified self-expanding Niti-S stent for the management of benign hypopharyngeal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:714-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Somani SK, Verma N, Avasthi G, Ghosh A, Goyal R, Joshi N. High pharyngoesophageal strictures after laryngopharyngectomy can also be treated by self-expandable plastic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1304-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anseline PF, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Radiation injury of the rectum: evaluation of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1981;194:716-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |