INTRODUCTION

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is an uncommon malignancy of the liver, and has been described in only a few reports in the English literature. The prevalence of PHL is 0.4% in extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and 0.016% in all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas[1]. The incidence of PHL has increased in recent years, and may be related to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. Due to its rarity, clinical manifestations and laboratory tests are non-specific, the disease is usually misdiagnosed preoperatively, and the final diagnosis depends on histological examination from liver biopsy. In the present report, we present a patient with pathologically confirmed primary hepatic diffuse large B cell lymphoma originating from the germinal center.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old woman presented with intermittent low-grade fever and weight loss of 10 kg in the previous 3 mo. She had no remarkable past medical history except for an operation for a benign gastric stromal tumor. She was admitted to our hospital due to right upper quadrant abdominal pain in June 2009. Gastroscopy of the esophagus suggested stromal tumor, and the patient underwent endoscopic resection of the esophageal stromal tumor. Immunohistochemical examination showed that the markers CD34, alpha-smooth muscle actin and Des were positive, and CD117 as well as S-100 were negative. On examination, the patient was in good spirits, the skin and mucosa were anicteric, there was no splenomegaly or enlarged superficial lymph nodes, and the liver was not palpable. Laboratory findings on admission were as follows: total white cell count 7.9 × 109/L, hematocrit 0.29 L/L, hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL; total bilirubin 11.6 μmol/L (normal range 3.4-20.5 μmol/L), aspartate aminotransferase 17 IU/L (normal range 0-60 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase 7 IU/L (normal range 0-60 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 123 IU/L (normal range 40-150 IU/L); lactate dehydrogenase 209.0 IU/L (normal range 135.0-215.0 IU/L), C-reactive protein 52.50 mg/L (normal range 0.00-80.00 mg/L), calcium 2.09 mmol/L (normal range 2.00-2.60 mmol/L); and positive antibody for hepatitis B virus, and negative antibody for hepatitis C virus. Serology for HIV was negative. The levels of tumor markers, such as alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were within normal limits. Chest X-ray did not reveal any abnormalities. On ultrasound, the lesion showed heterogeneous hypo-echoicity relative to normal hepatic parenchyma in the right liver and its border was clear, dotted blood flow could be seen around the edge of the lesion on Color Doppler imaging. Computed tomography showed a solid, cystic hypodense lesion in the right hepatic lobe measuring 10.0 cm × 6.1 cm on plain image. The enhancement image after injection of iodinated contrast revealed mild rim enhancement in the arterial phase. Obvious enhancement in the portal venous phase was observed (Figure 1). Primary hepatocarcinoma, liver abscess, and metastasis from the gastrointestinal tract were initially suspected. In order to make an accurate diagnosis and stage the lesion, the patient was referred for a whole body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan to identify other sites of involvement. The patient was injected with 6.1 millicuries of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and after 60 min of uptake time, she underwent a whole body scan in a dedicated PET/CT scanner. An abnormal ring-like metabolic focus in the right liver lobe was observed, with a maximum FDG uptake of 17.7 (Figure 2), the center exhibited less FDG uptake, and other body sites were negative. Hepatocarcinoma and liver abscess were suspected. In order to establish a diagnosis, ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed, and five strips of liver tissue were extracted from the lesion. However, examination of the tissue was inconclusive as it showed fibroplasia and hyaline degeneration interspersed with lymphocytes. The patient underwent open laparotomy and partial hepatectomy for diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 1 Obvious enhancement in the portal venous phase was observed.

A: A hypodense area in the right liver lobe was seen on plain computed tomography; B: The hypodense lesion showed mild rim enhancement in the arterial phase; C: Obvious enhancement was seen in the portal phase.

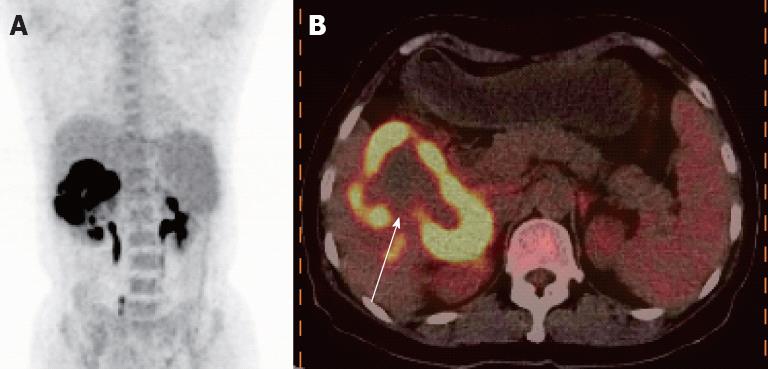

Figure 2 An abnormal ring-like metabolic focus in the right liver lobe was observed, with a maximum fluorodeoxyglucose uptake of 17.

7. A: Positron emission tomography/ computed tomography imaging showed a high metabolic focus in the right liver lobe; B: Fusion imaging revealed a ring-like high uptake focus with lower uptake in the center of the lesion (as shown by the white arrow).

There was no significant mesenteric or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, no ascites were observed in the abdominal cavity, and the gastrointestinal tract was normal. The tumor was located in segments IV and I of the right liver lobe adhered to the hepatic flexure of the colon and renal capsule.

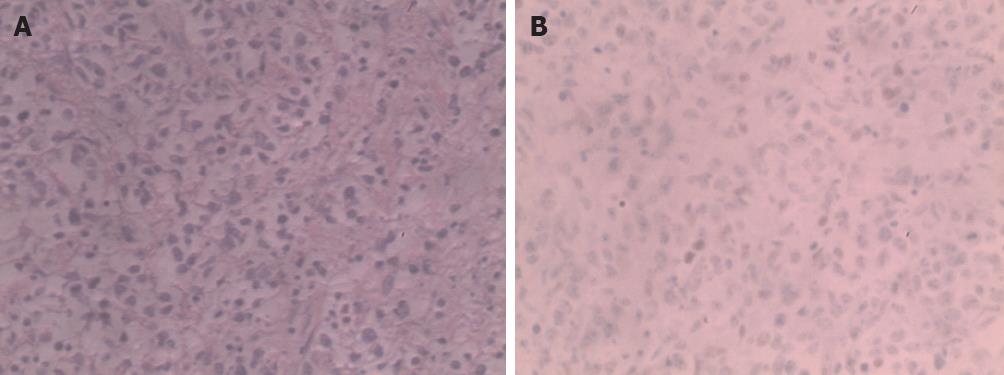

The intraoperative frozen section revealed a small round cell tumor. Microscopic histopathological examination showed a multinucleated giant cell tumor and hepatic sinusoidal infiltration, interstitial lymphocyte reactive hyperplasia with spotting hemorrhagic areas and necrosis. The surrounding liver tissues revealed intrahepatic cholestasis and lymphocytic infiltration around the bile ducts. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, Bc1-6, Mum-1 and Ki-67 (> 80%), and negative for CD30, Bcl-2, and cytokeratin (Figure 3). The diagnosis of diffuse B-cell lymphoma originating from the germinal center was made.

Figure 3 Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, Bc1-6, Mum-1, Ki-67 and negative for CD30, Bcl-2, cytokeratin.

A: The normal structure of liver tissue was damaged, and showed dysplastic, almost naked nuclear lymphocytes, diffuse infiltration of liver tissue, tumor cells were mainly composed of round and oval cells, and spindle, polygonal, and multinucleated giant tumor cells were also seen (hematoxylin and eosin, ×400); B: Bcl-6 was positive, and CD10 as well as Mum-1 were negative (immunohistochemistry, ×400).

The patient was discharged 2 wk after surgery, and did not receive chemotherapy or radiotherapy. After 25 mo follow-up, she was in good health.

DISCUSSION

PHL, which is defined as a lesion or lesions confined to the liver only without the involvement of any other organ or lymph nodes, is extremely rare, accounting for less than 0.01% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and can occur in any age group but is usually found in middle-aged men. The pathogenesis of PHL is unclear, and it is usually seen in organ transplant recipients, in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy and in individuals with AIDS. In recent years, studies have indicated that hepatitis C infection is strongly related to PHL, a possible cause is hepatitis C virus stimulating B lymphocytes and chronic polyclonal proliferation, leading to liver lymphoma[2,3].

The clinical manifestations are atypical including fever, weight loss, night sweat and right upper abdominal pain. Lactate dehydrogenase and blood calcium are sometimes elevated[4,5]. Primary hepatic lymphoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure with hyperferritinemia was described by Haider et al[6]. The most frequent pathology in PHL is diffuse large B cell followed by small lymphocytic, T cell, follicular and marginal B cell lymphoma. PHL responds to therapy and may have a better prognosis than hepatocellular carcinoma, as it is chemosensitive, and early aggressive combination chemotherapy may result in sustained remission[7].

Primary hepatic lymphoma has its own characteristic imaging features. It can be classified into 3 morphologic patterns: solitary liver mass, multiple focal nodules and diffuse infiltrative disease, the first 2 patterns are the most common[8], and an imaging study showed a solitary space-occupying lesion or multiple heterogeneous lesions which were well-defined suggesting hepatocarcinoma or metastasis from the gastrointestinal tract[9]. Elsayes et al[10] described 12 cases of PHL, three of which presented with a single focal lesion (25%), eight (67%) patients presented with multiple well-defined lesions, and one patient (8%) presented with diffuse hepatic involvement on CT imaging. The lesions in three patients demonstrated rim enhancement following intravenous iodinated contrast administration. The features of rim enhancement were similar to those in our case. PHLs are usually hypoechoic relative to normal liver on ultrasound imaging, and in a minority of cases, the lesions can be anechoic, hypoechoic areas with high perinodular and low intranodular vascularization on Doppler sonography, which are easily misdiagnosed as angiomas[11,12]. On contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, the lesion has mild inhomogeneous hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and wash-out in the portal and late phases[13]. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PHLs usually have moderate to high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and are mild to moderate hypointense relative to liver on T1-weighted images[14,15]. The enhanced image is variable, mainly manifestations of early intense ring or predominantly ring enhancement. The imaging features of PHL on ultrasound, MRI and CT have been reported, while the imaging features of PHL on PET and single photon emission computed tomography are relatively rare (the number of PET or PET/CT studies is small compared to the large number of ultrasound CT and MRI studies on PHL). PET/CT scanning which can produce whole body imaging data and distinguish primary liver lesions from metastatic disease is superior to CT, MRI and ultrasound which only visualize a limited portion of the body. Thus, PET/CT is advantageous in the diagnosis and treatment of liver lymphoma. To the best of our knowledge, three cases of multiple PHL and one case of diffuse infiltrative disease have been described using PET/CT imaging. While diffuse infiltrative disease is extremely rare, Kang et al[16] reported one case using PET imaging in the English literature, this type of PHL is easily misdiagnosed as hepatitis or diffuse cholangiocellular carcinoma. However, a solitary PHL on PET/CT imaging has not been reported. Whether primary or secondary lymphoma of the liver is present, imaging with FDG or Ga67 PET showed high uptake. In our case report, the lesion demonstrated a ring-like hypermetabolic area, which suggested tumor viability. The level of isotope uptake may correlate with disease activity and tumor proliferation[17,18].

In conclusion, PHL is a rare disease, its clinical symptoms, laboratory results, and imaging results are non-specific, therefore, it is difficult to establish a diagnosis immediately. Thus, when a solitary hypermetabolic lesion on PET/CT scanning is found in the liver and no other organ or tissue is involved, PHL should be considered, hepatoma and liver abscess should be excluded and a liver biopsy performed for further management.