Published online Dec 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7378

Revised: October 1, 2012

Accepted: November 11, 2012

Published online: December 28, 2012

Processing time: 170 Days and 15.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the effect of dietary fiber intake on constipation by a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

METHODS: We searched Ovid MEDLINE (from 1946 to October 2011), Cochrane Library (2011), PubMed for articles on dietary fiber intake and constipation using the terms: constipation, fiber, cellulose, plant extracts, cereals, bran, psyllium, or plantago. References of important articles were searched manually for relevant studies. Articles were eligible for the meta-analysis if they were high-quality RCTs and reported data on stool frequency, stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and gastrointestinal symptoms. The data were extracted independently by two researchers (Yang J and Wang HP) according to the described selection criteria. Review manager version 5 software was used for analysis and test. Weighted mean difference with 95%CI was used for quantitative data, odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI was used for dichotomous data. Both I2 statistic with a cut-off of ≥ 50% and the χ2 test with a P value < 0.10 were used to define a significant degree of heterogeneity.

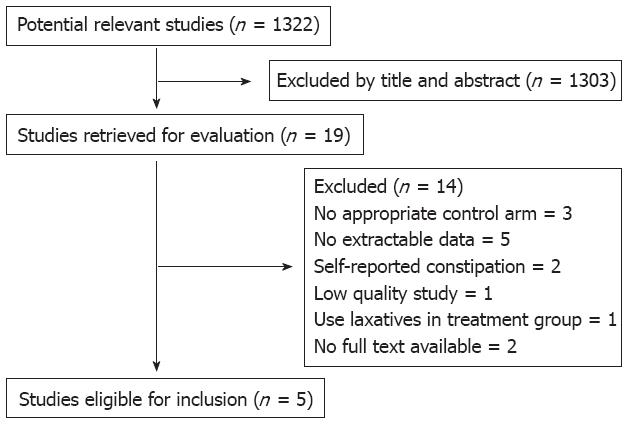

RESULTS: We searched 1322 potential relevant articles, 19 of which were retrieved for further assessment, 14 studies were excluded for various reasons, five studies were included in the analysis. Dietary fiber showed significant advantage over placebo in stool frequency (OR = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.58-1.80, P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and painful defecation between the two groups. Stool frequency were reported by five RCTs, all results showed either a trend or a significant difference in favor of the treatment group, number of stools per week increased in treatment group than in placebo group (OR = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.58-1.80, P < 0.05), with no significant heterogeneity among studies (I2= 0, P = 0.77). Four studies evaluated stool consistency, one of them presented outcome in terms of percentage of hard stool, which was different from others, so we included the other three studies for analysis. Two studies reported treatment success. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (P < 0.1, I2 > 50%). Three studies reported laxative use, quantitative data was shown in one study, and the pooled analysis of the other two studies showed no significant difference between treatment and placebo groups in laxative use (OR = 1.07; 95%CI 0.51-2.25), and no heterogeneity was found (P = 0.84, I2= 0). Three studies evaluated painful defecation: one study presented both quantitative and dichotomous data, the other two studies reported quantitative and dichotomous data separately. We used dichotomous data for analysis.

CONCLUSION: Dietary fiber intake can obviously increase stool frequency in patients with constipation. It does not obviously improve stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and painful defecation.

- Citation: Yang J, Wang HP, Zhou L, Xu CF. Effect of dietary fiber on constipation: A meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(48): 7378-7383

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i48/7378.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7378

Constipation is a health problem that influences almost 20% of the world’s population[1]. It is a bothersome disorder which negatively affect the quality of life and increase the risk of colon cancer[2]. There are a wide-range of treatment methods. Life-style modification, such as increased fluid intake or exercise, are usually recommended as first-line treatment, but data on the effectiveness of these measures are limited[3]. Laxatives are most commonly used for treatment of constipation, but frequent use of these drugs may lead to some adverse effects[4,5], alternative treatment measure is, therefore, needed. Soluble fiber absorbs water to become a gelatinous, viscous substance and is fermented by bacteria in the digestive tract. Insoluble fiber has a bulking action[6]. Dietary fiber is the product of healthful compounds and has demonstrated some beneficial effect. Increase of dietary fiber intake has been recommended to treat constipation in children and adults[7-9]. In a large-population case-control study, Rome found that dietary fiber intake was independently negatively correlated with chronic constipation, despite the age range and the age at onset of constipation[10]. Although there have been several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studying the relationship between dietary fiber and constipation, no definitive quantitative summary is available, therefore we conducted a meta-analysis of RCTs, and report it below.

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (from 1946 to October 2011), Cochrane Library (2011) and PubMed to identify RCTs studying dietary fiber and constipation. We used the following terms: constipation as medical subject headings and free text terms, which were combined with fiber, cellulose, plant extracts, cereals, bran, psyllium or plantago. References of important articles were searched manually for relevant studies.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) studies investigating the association between the intake of dietary fiber and constipation; (2) RCTs with a trial quality greater than or equal to 3 points judged by Jadad score; (3) constipation was defined by symptoms according to the Roma criteria or clinical diagnosis; (4) studies reporting at least one of the following data: stool frequency, stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use, gastrointestinal symptom; and (5) dietary fiber was used as the only active intervention in treatment group.

The data were extracted independently by two researchers (Yang J and Wang HP) according to the described selection criteria. Disagreement was resolved by discussion with the third person. The following data were extracted: the first author’s name, year of publication, study design, interventional method, study period, sample size, outcomes, method used to generate the randomization, level of blinding, withdrawn or drop-outs explanations.

Review manager version 5 software was used for all meta-analyses and tests for heterogeneity. Weighted mean difference with 95%CI was used for quantitative data, odds ratio with 95%CI was used for dichotomous data. Both I2 statistic with a cut-off of ≥ 50% and the χ2 test with a P value < 0.10 were used to define a significant degree of heterogeneity. Random-effects model was applied. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We searched 1322 potential relevant articles, 19 of which were retrieved for further assessment, and 14 studies were excluded for the reasons as shown in Figure 1. As a result, five studies were included, and the characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 1.

| Study | Trial design | No. of patients | Interventional method | Duration (wk) | Randomized allocation/double-blind/description of withdrawn and dropouts | Jadad score |

| Badiali et al[11] | Double-blind crossover | 24 (adults) | Bran 20 g (fiber 12.5 g) vs placebo | 4 | Y/Y/Y | 4 |

| Loening-Baucke et al[12] | Double-blind crossover | 31 (children) | Glucomannan 100 mg/kg vs placebo | 4 | Y/Y/Y | 5 |

| Castillejo et al[13] | Double-blind | 48 (children) | Fiber supplement 5.2 g (53.2% fiber) 2 or 4 sachets vs placebo | 4 | Y/Y/Y | 5 |

| Chmielewska et al[14] | Double-blind | 72 (children) | Glucomannan 2.52 g vs placebo | 4 | Y/Y/Y | 5 |

| Staiano et al[15] | Double-blind | 20 (children) | Glucomannan 200 mg/kg vs placebo | 12 | Y/Y/Y | 4 |

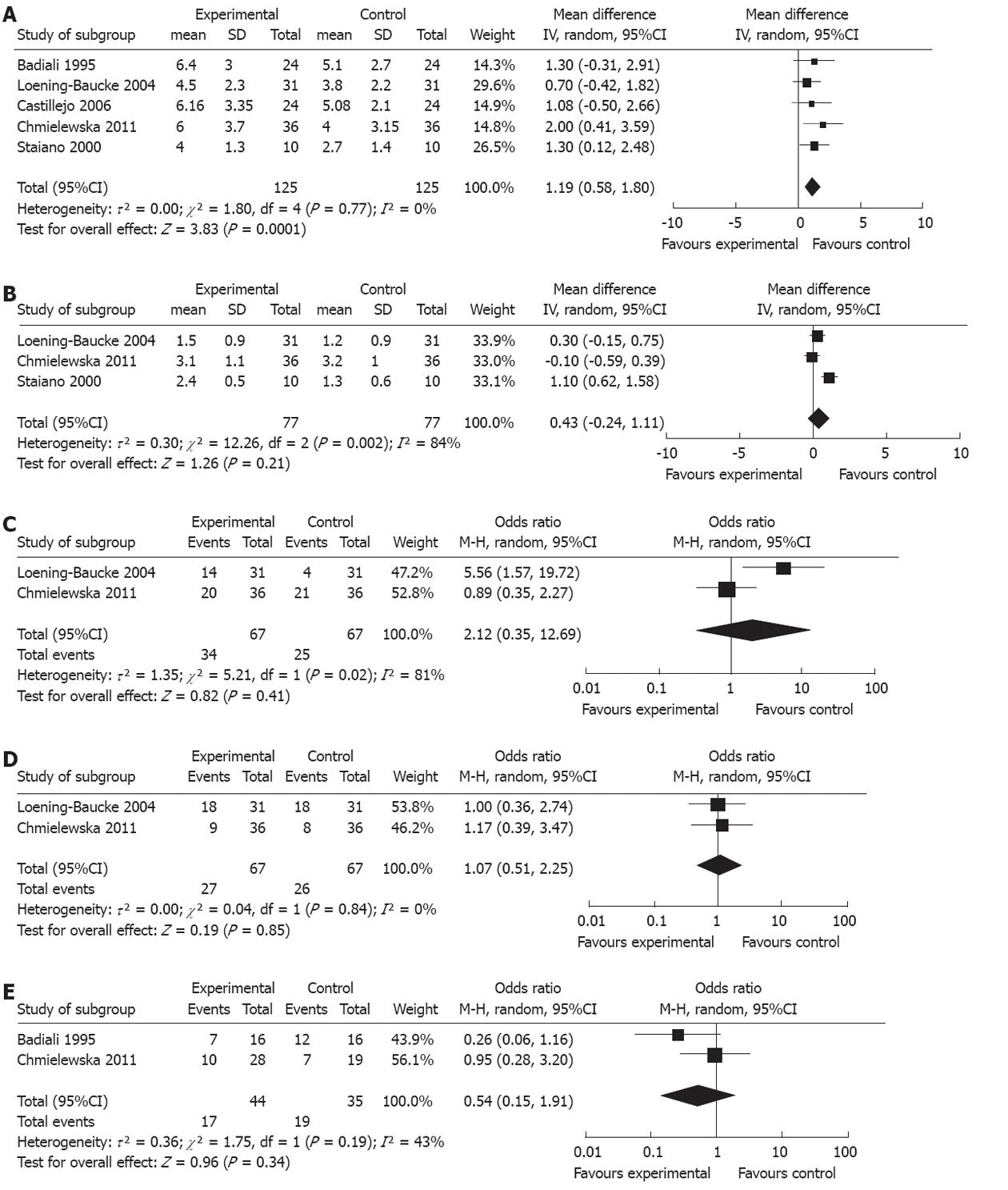

Stool frequency was reported by five RCTs[11-15]. Results showed either a trend or a significant difference in favor of the treatment group, and an increased number of stools per week in treatment group compared with the placebo group [odds ratio (OR) = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.58-1.80, P < 0.05], with no significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 0, P = 0.77). Of note, stool frequency was expressed as median (interquartile range) in Chmielewska’s study [14], and we used the formula to transform it into mean ± SD (Figure 2A)[16].

Four studies evaluated stool consistency[12-15], one of them presented outcome in terms of percentage of hard stool[13], which was different from others, so we included the other three studies for analysis. Results showed no statistical difference between two groups (OR = 0.43; 95%CI: -0.24-1.11, P > 0.05), however substantial heterogeneity existed (P < 0.1, I2 > 75%) (Figure 2B).

Two studies reported treatment success[12,14]. The pooled analysis (Figure 2C) for overall results found significant difference between groups (OR = 2.21; 95%CI: 0.35-12.69, P > 0.05). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (P < 0.1, I2 > 50%).

Three studies reported laxative use[12,14,15], quantitative data was shown in one study[15], and the pooled analysis (Figure 2D) of the other two studies showed no significant difference between treatment and placebo groups in laxative use (OR = 1.07; 95%CI: 0.51-2.25, P = 0.85), and no heterogeneity was present (P = 0.84, I2 = 0%).

Three studies evaluated painful defecation[11,14,15]: one study presented both quantitative and dichotomous data[14], the other two studies separately reported quantitative and dichotomous data[11,15]. Evaluation method for quantitative data was different, one used actual frequency, the other two used frequency of occurrence (often/occasional/none). We used dichotomous data for analysis. The pooled estimate (Figure 2E) showed a nonsignificant trend in favor of treatment group (OR = 0.54; 95%CI: 0.15-1.91, P = 0.34). No statistically significant heterogeneity was present, but I2 was moderate (P > 0.1, I2 = 43%).

This meta-analysis shows that the number of stools was increased significantly in dietary fiber group. Results demonstrated either a trend or a significant difference in favor of dietary fiber group. As for stool consistency, the overall results showed a trend in favor of fiber group, but no statistical difference was found. The substantial heterogeneity may influence the results, and the heterogeneity may be caused by different rating scale, ranging from 0 to 4, from 0 to 5 and from 0 to 7 in three included studies, respectively. Although the rating sequence is unanimous, with a higher score indicating looser stools, different scale range may still influence the final results. Stool consistency was present as hard stool percentage in another included study[13], 41.7% and 75% of the patients who received dietary fiber or placebo, respectively, reported hard stools, the percentage being obviously lower in the dietary fiber group.

Two high-quality RCTs compared dietary fiber with lactulose for treatment of constipation[17,18], and found that dietary fiber and lactulose achieved comparable results in the treatment of childhood constipation. Dietary fiber is as effective as lactulose in improving stool frequency, stool consistency and treatment success, however, no difference was observed in treatment success between dietary fiber and placebo group in our meta-analysis. The possible reason was discussed. Constipation condition was more severe in the patients in Chmielewska’s study, who had a lower baseline stool frequency per week and a higher percentage of hard stool than the studies mentioned above[17,18] and the other study[12] used for analysis. It suggests that dietary fiber may not be so effective in severe constipation and can only be used in mild to moderate constipation, or perhaps the dosage of glucomannan (2.52 g/d) used in Chmielewska’s study is not high enough to exert effect. Nurko et al[19] suggested that behavior modification, such as parental positive reinforcement and good patient-doctor relationship, may have impact on the treatment outcome. So the effect of dietary fiber on different grades of constipation should be explored in further studies and it is also important to balance the behavior factors in comparison.

Dichotomous data was used to analyze the laxative use in our study, which can only reflect how many patients used the laxatives, but not indicate how often it was used. Quantitative data about laxative use can better reflect the degree of dependence. If the time when laxative was used is described, the outcome will be more useful for overall analysis.

Gastrointestinal symptoms were reported by several studies. Because data was presented by different methods, only painful defecation was analyzed, and results showed that there was no significant difference between dietary fiber and placebo groups.

We used rigid research methods and described search strategy, eligibility criteria and data extraction method in detail. We included high-quality studies (Jadad score ≥ 3) into the analysis. Because of the strict selection criteria, only five small sample-sized studies were included. Definite heterogeneity existed in the analysis. Neurologically impaired children were included, although no difference was present between dietary fiber and placebo groups during baseline period, disease itself can interfere with the outcome. Some of the studies are limited to pediatric patients, stool withholding and stool toileting refusal often occurred[20], which is uncommon among constipated adults, although no heterogeneity was found in the analysis of stool frequency, potential limitation still existed. As scarce data of gastrointestinal syndromes was reported, and different evaluation and presentation methods were used, less data can be used for the analysis.

There were meta-analyses examining the efficacy of fiber in constipation previously, in which data of fiber and laxative were pooled for analysis[21,22]. Recently, a systematic review of the efficacy of fiber in the management of chronic idiophic constipation was published[23], six RCTs were included, four RCTs compared the effect of soluble fiber with placebo[24-27], and one study[27] used the combined intervention with celandine, aloevera and psyllium. Celandin and aloevera contain several alkaloids with known aperient effect, which may influence the outcome of the patients. Of the two trials examining the effect of insoluble fiber[11,28], one trial[28] recruited patients with self-reported constipation, subjective error may be more obvious when the outcome was assessed by non-medical staff.

In summary, our meta-analysis demonstrated that dietary fiber can obviously increase stool frequency in patients with constipation. The result also showed that dietary fiber did not obviously improve stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and painful defecation. However, there were some possible influential factors such as small sample-sized studies, severity of constipation, assessment method for outcomes, etc. So further large trials examining the effect of dietary fiber in the treatment of constipation are needed, the possible influential factors should be taken into consideration, and more gastrointestinal symptoms and adverse events should be reported before dietary fiber was formally recommended.

Constipation is one of the widespread health problems. There is a wide-range of treatment methods. Life-style modification is usually recommended as first-line treatment, but data on the effectiveness of these measures are limited. Laxatives are most commonly used for treatment of constipation, but frequent use of these drugs may lead to some adverse effects, and alternative treatment measure is therefore needed. Increase of dietary fiber intake has been recommended to treat constipation of children and adults. There have been several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studying the relationship between dietary fiber and constipation, however no definitive quantitative summary is available.

Some studies reported that dietary fiber can increase stool frequency, improve stool consistency and have no obviously adverse effects. Two studies concluded that dietary fiber is as effective as lactulose treatment and seems to have less side effects. However, in another study, dietary fiber was not found more effective than placebo in therapeutic success and it might increase the frequency of abdominal pain.

This meta-analysis demonstrated that dietary fiber can obviously increase stool frequency in patients with constipation. The result also showed that dietary fiber did not obviously improve stool consistency, treatment success, laxative use and painful defecation, however, there were some possible influential factors such as small sample-sized studies, severity of constipation, and assessment method for outcomes. Further large trials examining the effect of dietary fiber in the treatment of constipation are needed, the possible influential factors should be taken into consideration and more gastrointestinal symptoms and adverse events should be reported before dietary fiber was formally recommended.

The study results suggest that dietary fiber intake is a potential therapeutic method that could be used in the treatment of constipation.

Constipation: Present with any two of the six symptoms of less than 3 defecations per week, straining, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, digital maneuvers; Dietary fiber: Dietary fiber is a broad category of non-digestible food ingredients that includes non-starch polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, lignin, and analogous polysaccharides with an associated healthful benefit.

The effectiveness of dietary fiber on constipation is inconsistent. So far no definitive quantitative summary is available. This is a well performed meta-analysis, in which the authors analyzed the effect of dietary fiber in constipation. The results are interesting and suggest that dietary fiber intake is a potential therapeutic method that could be used in preventing and treating constipation. This analysis provides valuable information for further trials and clinical application.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Giuseppe Chiarioni, Gastroenterological Rehabilitation Division of the University of Verona, Valeggio sul Mincio Hospital, Azienda Ospedale di Valeggio s/M, 37067 Valeggio s/M, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in RCA: 676] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Watanabe T, Nakaya N, Kurashima K, Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, Tsuji I. Constipation, laxative use and risk of colorectal cancer: The Miyagi Cohort Study. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2109-2115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Johanson JF. Review of the treatment options for chronic constipation. MedGenMed. 2007;9:25. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Xing JH, Soffer EE. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1201-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wald A. Is chronic use of stimulant laxatives harmful to the colon? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:386-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, Waters V, Williams CL. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:188-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1158] [Cited by in RCA: 1135] [Article Influence: 70.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Loening-Baucke V. Chronic constipation in children. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1557-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marlett JA, McBurney MI, Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:993-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jenkins DJ, Jenkins AL. The clinical implications of dietary fiber. Adv Nutr Res. 1984;6:169-202. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Roma E, Adamidis D, Nikolara R, Constantopoulos A, Messaritakis J. Diet and chronic constipation in children: the role of fiber. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Badiali D, Corazziari E, Habib FI, Tomei E, Bausano G, Magrini P, Anzini F, Torsoli A. Effect of wheat bran in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation. A double-blind controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:349-356. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Loening-Baucke V, Miele E, Staiano A. Fiber (glucomannan) is beneficial in the treatment of childhood constipation. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e259-e264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Castillejo G, Bulló M, Anguera A, Escribano J, Salas-Salvadó J. A controlled, randomized, double-blind trial to evaluate the effect of a supplement of cocoa husk that is rich in dietary fiber on colonic transit in constipated pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e641-e648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chmielewska A, Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. Glucomannan is not effective for the treatment of functional constipation in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Staiano A, Simeone D, Del Giudice E, Miele E, Tozzi A, Toraldo C. Effect of the dietary fiber glucomannan on chronic constipation in neurologically impaired children. J Pediatr. 2000;136:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Whitlock RP, Chan S, Devereaux PJ, Sun J, Rubens FD, Thorlund K, Teoh KH. Clinical benefit of steroid use in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2592-2600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Üstündağ G, Kuloğlu Z, Kirbaş N, Kansu A. Can partially hydrolyzed guar gum be an alternative to lactulose in treatment of childhood constipation? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:360-364. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kokke FT, Scholtens PA, Alles MS, Decates TS, Fiselier TJ, Tolboom JJ, Kimpen JL, Benninga MA. A dietary fiber mixture versus lactulose in the treatment of childhood constipation: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nurko S, Youssef NN, Sabri M, Langseder A, McGowan J, Cleveland M, Di Lorenzo C. PEG3350 in the treatment of childhood constipation: a multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2008;153:254-261, 261.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Dijk M, Benninga MA, Grootenhuis MA, Nieuwenhuizen AM, Last BF. Chronic childhood constipation: a review of the literature and the introduction of a protocolized behavioral intervention program. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:63-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tramonte SM, Brand MB, Mulrow CD, Amato MG, O'Keefe ME, Ramirez G. The treatment of chronic constipation in adults. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2222-2230. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Suares NC, Ford AC. Systematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:895-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ashraf W, Park F, Lof J, Quigley EM. Effects of psyllium therapy on stool characteristics, colon transit and anorectal function in chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:639-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fenn GC, Wilkinson PD, Lee CE, Akbar FA. A general practice study of the efficacy of Regulan in functional constipation. Br J Clin Pract. 1986;40:192-197. [PubMed] |

| 26. | López Román J, Martínez Gonzálvez AB, Luque A, Pons Miñano JA, Vargas Acosta A, Iglesias JR, Hernández M, Villegas JA. The effect of a fibre enriched dietary milk product in chronic primary idiopatic constipation. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23:12-19. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Odes HS, Madar Z. A double-blind trial of a celandin, aloevera and psyllium laxative preparation in adult patients with constipation. Digestion. 1991;49:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hongisto SM, Paajanen L, Saxelin M, Korpela R. A combination of fibre-rich rye bread and yoghurt containing Lactobacillus GG improves bowel function in women with self-reported constipation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:319-324. [PubMed] |