Published online Dec 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7333

Revised: October 31, 2012

Accepted: November 11, 2012

Published online: December 28, 2012

Processing time: 137 Days and 19.8 Hours

AIM: To investigate the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and its related risk factors in Uygur and Han Chinese adult in Urumqi, China.

METHODS: A population-based cross-sectional survey was undertaken in a total of 972 Uygur (684 male and 288 female) aged from 24 to 61 and 1023 Han Chinese (752 male and 271 female) aged from 23 to 63 years. All participants were recruited from the residents who visited hospital for health examination from November 2011 to May 2012. Each participant signed an informed consent and completed a GERD questionnaire (Gerd Q) and a lifestyle-food frequency questionnaire survey. Participants whose Gerd Q score was ≥ 8 and met one of the following requirements would be enrolled into this research: (1) being diagnosed with erosive esophagitis (EE) or Barrett’s esophagus (BE) by endoscopy; (2) negative manifestation under endoscopy (non-erosive reflux disease, NERD) with abnormal acid reflux revealed by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring; and (3) suffering from typical heartburn and regurgitation with positive result of proton pump inhibitor test.

RESULTS: According to Gerd Q scoring criteria, 340 cases of Uygur and 286 cases of Han Chinese were defined as GERD. GERD incidence in Uygur was significantly higher than in Han Chinese (35% vs 28%, χ2 = 11.09, P < 0.005), Gerd Q score in Uygur was higher than in Han Chinese (7.85 ± 3.1 vs 7.15 ± 2.9, P < 0.005), and Gerd Q total score in Uygur male was higher than in female (8.15 ± 2.8 vs 6.85 ± 2.5, P < 0.005). According to normalized methods, 304 (31%) cases of Uygur were diagnosed with GERD, including 89 cases of EE, 185 cases of NERD and 30 cases of BE; 256 (25%) cases of Han Chinese were diagnosed with GERD, including 90 cases of EE, 140 cases of NERD and 26 cases of BE. GERD incidence in Uygur was significantly higher than in Han Chinese (31% vs 25%, χ2 = 9.34, P < 0.005) while the incidences were higher in males of both groups than in females (26% vs 5% in Uygur, χ2 = 35.95, P < 0.005, and 19.8% vs 5.2% in Han, χ2 = 5.48, P < 0.025). GERD incidence in Uygur male was higher than in Han Chinese male (26% vs 19.8%, χ2 = 16.51, P < 0.005), and incidence of NERD in Uygur was higher than in Han Chinese (χ2 = 10.06, P < 0.005). Occupation (r = 0.623), gender (r = 0.839), smoking (r = 0.322), strong tea (r = 0.658), alcohol drinking (r = 0.696), meat-based diet (mainly meat) (r = 0.676) and body mass index (BMI) (r = 0.567) were linearly correlated with GERD in Uygur (r = 0.833, P = 0.000); while gender (r = 0.957), age (r = 0.016), occupation (r = 0.482), strong tea (r = 1.124), alcohol drinking (r = 0.558), meat diet (r = 0.591) and BMI (r = 0.246) were linearly correlated with GERD in Han Chinese (r = 0.786, P = 0.01). There was no significant difference between Gerd Q scoring and three normalized methods for the diagnosis of GERD.

CONCLUSION: GERD is highly prevalent in adult in Urumqi, especially in Uygur. Male, civil servant, smoking, strong tea, alcohol drinking, meat diet and BMI are risk factors correlated to GERD.

- Citation: Niu CY, Zhou YL, Yan R, Mu NL, Gao BH, Wu FX, Luo JY. Incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Uygur and Han Chinese adults in Urumqi. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(48): 7333-7340

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i48/7333.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7333

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common acid-related disease worldwide, and severely affects the quality of life of patients. The incidence of GERD is high in Western and developed countries, however, due to changes in lifestyle and dietary habits the incidence of GERD has increased in the Asian-Pacific region in recent years[1,2], particularly in China. This is due to the introduction of Western fast food into the Chinese dietary structure which has had a significant influence since its introduction ten years ago. The incidence of GERD in China is rising year by year[3], and is showing a “low in south and high in north” trend[4]. Xinjiang is located in the Northwest region of China, and Uygur is the main minority group in this autonomous region of China. An important dietary custom in local residents is to prioritize meat (mainly beef and lamb), cooked wheaten food, and alcohol drinking. In addition, strong tasting foods are favored. Together with the development of social and cultural diversity, there appears to have been culture blendings and interactions between Uygur and Han Chinese as time goes by. In addition to these factors, the particular geographic and climatic characteristics of Xinjiang exert an influence on the lifestyle and dietary customs of local inhabitants. Therefore, there are currently both similarities and differences between Uygur and Han Chinese with regard to lifestyle and dietary customs. Furthermore, genetics studies have revealed that the Han Chinese gene contains Oriental Mongoloid characteristics, while the Uygur gene contains both Caucasian and Oriental Mongoloid characteristics. To our knowledge, there has been little research focusing on the incidence of GERD with regard to minority groups[5], and large-scale studies focusing on GERD in the Uygur population alone have not been carried out. Based on the above research background, we aimed to elucidate the following: (1) Does lifestyle and dietary customs or dietary structure in Xinjiang inhabitants impact on GERD occurrence; (2) differences in the incidence of GERD in Uygur and Han Chinese; and (3) potential risk factors related to GERD, and provide guidance in clinical practice.

This study was a population-based cross-sectional, randomized, single center, open-label trial. A total of 972 Uygur (684 males and 288 females) aged 24 to 61 years and 1023 Han (752 males and 271 females) aged 23 to 63 years living in Urumqi were enrolled into this study. All participants, who were residents of Xinjiang, China (college students, workers and civil servants) were recruited from those who attended the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University for a health examination from November 2011 to May 2012. All participants signed an informed consent before participating in this research. Each subject completed a GERD questionnaire (Gerd Q) scale and a lifestyle-food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).

Participants whose Gerd Q score was ≥ 8 and who met one of the following requirements were enrolled in this study: (1) diagnosed with erosive esophagitis (EE) or Barrett’s esophagus (BE) on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; (2) negative manifestations on endoscopy (non-erosive reflux disease, NERD) with abnormal acid reflux revealed by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring; and (3) suffering from typical heartburn and regurgitation with a positive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) test.

Any participant who met one of the following requirements was excluded from this study: (1) receiving a PPI or H2 receptor blocker; (2) suffered from serious gastrointestinal diseases (esophageal stricture, peptic ulcer, esophagus or stomach tumor) or a history of abdominal surgery; (3) suffered from major organ insufficiency; and (4) pregnant and lactating women.

Alcohol consumption in individuals was estimated by multiplying the mean weekly alcohol intake by the concentration of alcohol (12% alcohol for wine or 4% alcohol for beer). Alcohol intake per week of ≥ 140 g for males and ≥ 70 g for females was assessed as alcohol consumption. If a participant smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day then he/she was assessed as a smoker. Tea consumption over the past month was determined using a FFQ[6]. Nutritional intake was assessed using a validated 110-item FFQ (the Block 98)[7]. Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 was defined as overweight.

Total cumulative Gerd Q score was calculated by a gastroenterologist according to Gerd Q after questioning each participant about his or her symptoms during the previous 7 d. Subjects whose Gerd Q score was ≥ 8 were estimated to have pathological acid reflux[8] (Table 1).

| Symptom | Symptoms in the past 7 d | 0 d | 1 d | 2-3 d | 4-7 d |

| Positive symptom | Heart burn | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Regurgitation | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Negative symptom | Upper abdominal pain | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Nausea | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Positive affect | Sleeping disorder | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Extra medication | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Subjects who were willing to undergo endoscopy were instructed to stop all medications that affected alimentary motility and endocrine function, and then fasted for at least 8 h. The presence or absence of reflux esophagitis, endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia and hiatal hernia were determined by specialized endoscopists. If EE was present, it was graded according to the Los Angeles classification[9]. The diagnosis of BE was based on endoscopy and pathology[10].

Subject who were willing to undergo 24-h esophageal pH monitoring were instructed to stop all medications that affected alimentary motility and endocrine function for at least 2 wk. Ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH monitoring was performed after fasting for at least 8 h. Single-use pH electrodes were placed 5 cm above the proximal margin of the lower esophageal sphincter. The subjects were encouraged to eat regular meals, however, the intake of food and drink with a pH below 4 was restricted. All subjects recorded their meal times (start and end), body position (supine and upright), and any symptoms in a diary. The data were collected using a portable data logger (Digitrapper Mark III, Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden) with a sampling rate of 4 s, and were transferred to a computer for analysis. The variables assessed for gastroesophageal reflux in the distal probe were the total percentage of time the pH was < 4, the percentage of time the pH was < 4 in the supine and upright positions, the number of episodes where the pH was < 4, the number of episodes the pH was < 4 for ≥ 5 min, the duration of the longest episode where the pH was < 4 and the DeMeester composite score[11]. A DeMeester score ≥ 14.72 was considered abnormal.

All measured data were expressed as mean ± SD. The χ2 test, U test and analysis of variance were used for comparisons between the groups, linear regression and multivariate logistic regression (backward) analyses were used for related factors analysis. Values of P < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using SPSS version 20.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics 20).

There were no statistically significant differences between the Uygur and Han participants in terms of occupation, gender, age, smoking (long-term and excessive smoking) and alcohol consumption (chronic overdrinking), however, there was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of dietary customs (mainly meat compared with mainly vegetarian) (Table 2).

| Ethnic group | n | Occupation(college students, workers/civil servants) | Gender(male/female) | Age(yr) | Smoking(yes/no) | Alcohol drinking(yes/no) | Diet custom(mainly meat/mainly vegetable) |

| Uygur | 972 | 497/475 | 684/288 | 43 ± 8.5 | 643/329 | 665/307 | 952/20 |

| Han | 1023 | 572/451 | 752/271 | 44 ± 9.1 | 728/295 | 725/298 | 297/726 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.000 |

According to Gerd Q scoring criteria, a total score of ≥ 8 was regarded as the assessment point. GERD was detected in 340 Uygur participants (incidence 35%) and in 286 Han participants (incidence 28%). The incidence of GERD in Uygur was significantly higher than that in Han Chinese (χ2 = 11.09, P < 0.005). The Gerd Q score in Uygur (7.85 ± 3.1) was higher than that in Han (7.15 ± 2.9) (P < 0.005), and the Gerd Q total score in Uygur males (8.15 ± 2.8) was higher than that in females (6.85 ± 2.5) (P < 0.005) (not listed in Table 2).

All participants who had been diagnosed with GERD using the Gerd Q scale underwent further endoscopy. Mucosal lesions were diagnosed as EE or BE, respectively, according to pertinent criteria, while those participants who did not have positive endoscopy findings underwent one of the following examinations: 24-h esophageal pH monitoring or the PPI test, and if any one of these two examinations was positive, the participant was diagnosed with NERD. According to the above three normalized methods (upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, 24-h esophageal pH monitoring and the PPI test), 304 Uygur participants were diagnosed with GERD (incidence 31%), including 89 cases of EE, 185 cases of NERD and 30 cases of BE; 256 Han participants were diagnosed with GERD (incidence 25%), including 90 cases of EE, 140 cases of NERD and 26 cases of BE. The incidence of GERD in Uygur was significantly higher than that in Han, and the incidence of GERD in male Uygur and Han was higher than that in female Uygur and Han, respectively (Table 3).

There was no significant difference between Gerd Q scoring criteria and the three normalized methods regarding the diagnosis of GERD (Uygur: χ2= 1.48, P > 0.5; Han: χ2= 0.83, P > 0.5) (not listed in Table 3).

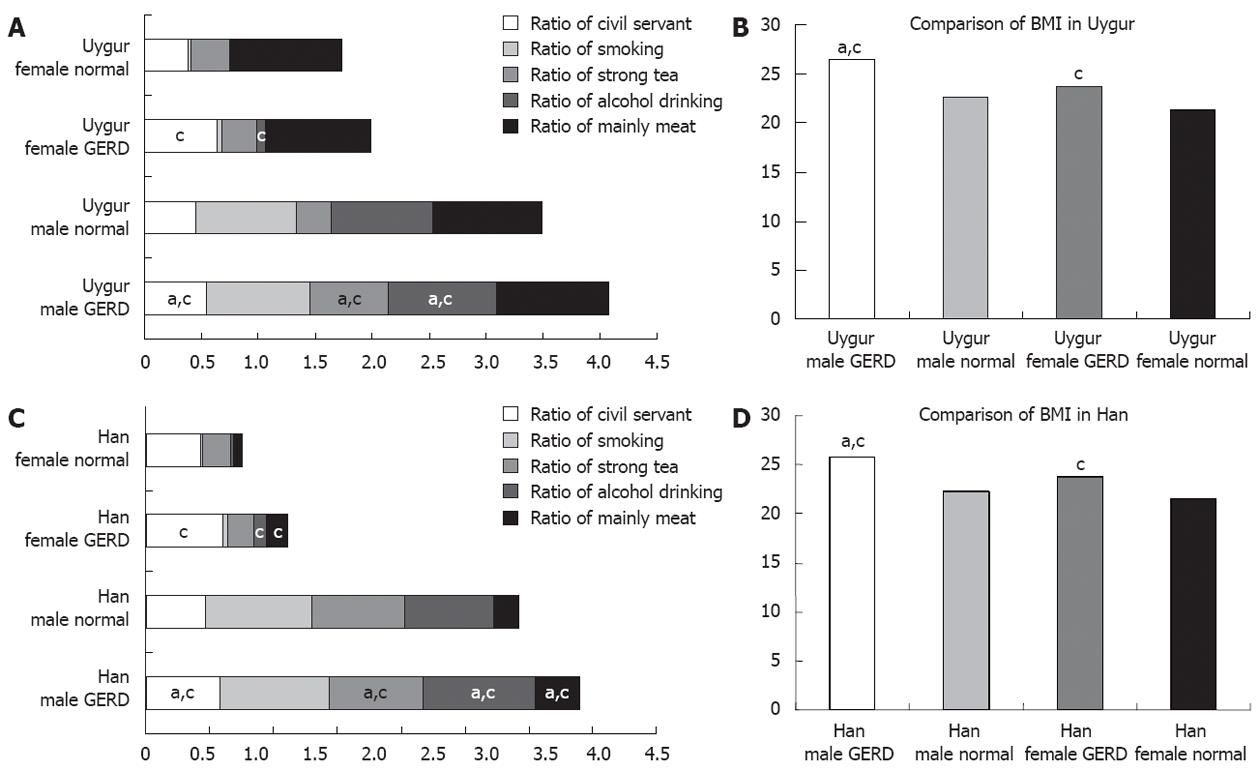

We compared the GERD groups and normal groups, and analyzed the relationship between the following factors and GERD using the U and χ2 tests in order to illustrate their potential impact on the occurrence of GERD (Figure 1). We found that, occupation (civil servant) and BMI were the collective factors related to GERD shared by the two ethnic groups and both genders; in Uygur participants with GERD, both males and females were correlated with strong tea and alcohol drinking (Figure 1A and B); while for Han participants with GERD, both males and females were correlated with strong tea, alcohol drinking and dietary custom (mainly meat) (Figure 1C and D).

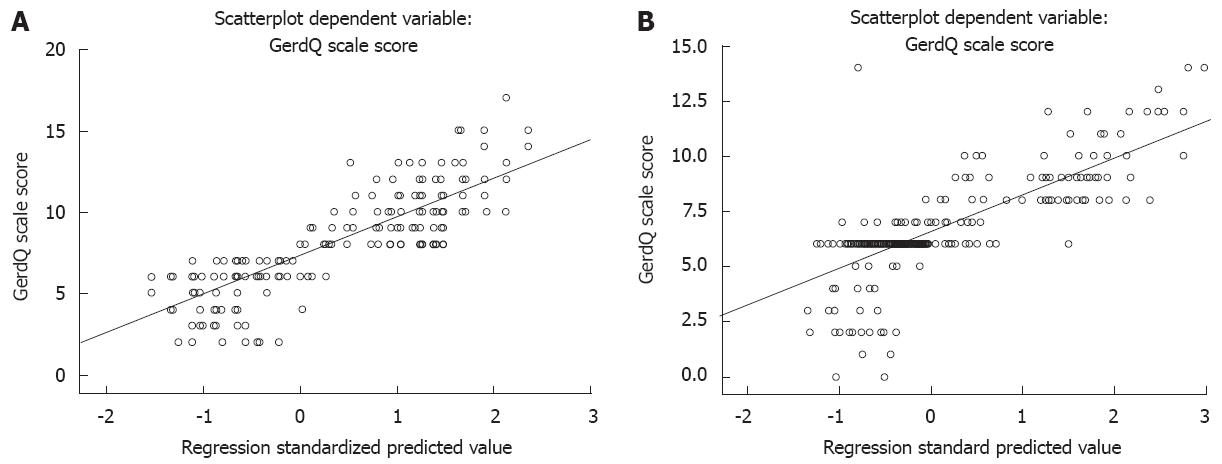

We analyzed the correlation between GERD and these factors further using a multivariate linear statistical method. The relationships between the risk factors for GERD in the two ethnic groups are listed below (Table 4 and Figure 2). Seven factors were found to correlate with GERD in Uygur and Han Chinese, respectively.

| Uygur | Han Chinese | ||||||||||

| Risk factor | B | Std. E | Beta | t | P value | Risk factor | B | Std. E | Beta | t | P value |

| Occupation | 0.623 | 0.169 | 0.115 | 3.079 | 0.005 | Occupation | 0.957 | 0.218 | 0.208 | 4.393 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.839 | 0.271 | 0.136 | 3.132 | 0.002 | Gender | -0.016 | 0.005 | -0.06 | -3.059 | 0.002 |

| Smoking | 0.322 | 0.123 | 0.064 | 2.614 | 0.009 | Smoking | 0.482 | 0.088 | 0.113 | 5.449 | 0.000 |

| Strong tea | -0.658 | 0.140 | -0.134 | -4.797 | 0.000 | Strong tea | -1.124 | 0.142 | -0.233 | -7.935 | 0.000 |

| Drinking | -0.696 | 0.145 | -0.138 | -4.805 | 0.000 | Drinking | -0.558 | 0.112 | -0.128 | -4.971 | 0.000 |

| Mainly meat | -0.676 | 0.168 | -0.132 | -4.011 | 0.000 | Mainly meat | -0.591 | 0.165 | -0.092 | -3.579 | 0.000 |

| BMI | 0.567 | 0.029 | 0.638 | 19.653 | 0.000 | BMI | 0.246 | 0.034 | 0.265 | 7.183 | 0.000 |

After removing age as a risk factor, the backward elimination method revealed that seven factors showed a significant linear correlation with GERD in Uygur participants (Table 4): occupation (r = 0.623), gender (r = 0.839), smoking (r = 0.322), strong tea (r = 0.658), alcohol drinking (r = 0.696), mainly meat (r = 0.676) and BMI (r = 0.567). Accordingly, the regression equation was: y (GERD) = -6.464 + 0.623 × occupation + 0.839 × gender + 0.322 × smoking - 0.658 × strong tea - 0.696× drinking - 0.676 × mainly meat + 0.567 × BMI (r = 0.833, P = 0.000) (Figure 2A).

For Han Chinese, seven factors showed a significant linear correlation with GERD: gender (r = 0.957), age (r = 0.016), occupation (r = 0.482), strong tea (r = 1.124), alcohol drinking (r = 0.558), mainly meat (r = 0.591) and BMI (r = 0.246), particularly strong tea and BMI (Table 4). Accordingly, the regression equation was: y (GERD) = -4.882 + 0.957 × gender - 0.016 × age + 0.482 × occupation - 1.124 × tea - 0.558 × drinking - 0.591 × meat + 0.246 × BMI (r = 0.793, P = 0.008) (Figure 2B).

GERD is a chronic disorder which has a significant impact on quality of life, and consumes a large number of medical resources worldwide. The incidence of GERD is higher than ever, particularly in Asian countries and China. Many publications on GERD have focused on southern China, however, there are few reports which have focused on northern China or minority groups. Therefore, the purpose of our large-scale, population-based investigation was to determine whether lifestyle and dietary customs of the local residents in Xinjiang play a role in GERD, whether the incidence of GERD is different between Uygur and Han Chinese, and which risk factors can lead to GERD.

By applying normalized methods (upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, 24-h esophageal pH monitoring and the PPI test), a total of 304 Uygur (31%) and 256 Han (25%) participants were classified as having GERD, 61% had NERD, 29% had EE and 10% had BE in the Uygur GERD group (254 male and 50 female), and in the Han group (203 male and 53 female), 55% had NERD, 35% had EE and 10% had BE. The incidence of GERD in Uygur was significantly higher than that in Han Chinese adults. The results of the present investigation also showed that the incidence of GERD in both Uygur and Han male adults was higher than that in Uygur and Han female adults, respectively. In addition, the incidence of NERD in Uygur was higher than that in Han. Using stratification analysis, we found that in Uygur with GERD, civil servant ratio, strong tea ratio, alcohol drinking ratio and BMI value in males were higher than those in normal males and females, respectively. The civil servant ratio, alcohol drinking ratio and BMI value in Uygur females with GERD were higher than those in normal females. In Han with GERD, the same results as those described in Uygur were observed, however, the mainly meat ratio in both males and females with GERD was higher than that in normal males and females. Regression analysis further revealed a correlation between seven factors and GERD in Uygur and Han participants, respectively. The above results indicated the presence of ethnic and gender differences between Uygur and Han Chinese with regard to GERD in China. The correlation between occupation, alcohol drinking as well as BMI and GERD was similar to previous studies[12-14]. A recent study found that the incidence of GERD in Caucasians was higher than that in other ethnic groups, which suggested that Caucasian was a related factor[15]. Anthropology research has demonstrated that the gene structure in Uygur subjects contains Caucasian and Mongolian bloodlines[16,17], thus the gene fusion characteristics in Uygur may reasonably explain their different phenotype with regard to GERD, which is not only different from but also similar to that of Han Chinese. The mainly meat ratio in both male and female Han participants with GERD was higher than that in normal males and females, respectively, and may be an independent risk factor associated with GERD. Although we cannot explain this result in Han at present, further research is needed in order to determine whether this result is objective, and whether ethnic groups or gene polymorphisms are related to GERD occurrence[18,19].

It has been shown that there are geographic and population (gender, age, ethnic group) differences in the incidence of GERD[20]. Related GERD etiological factors include BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, esophageal hiatus, and inheritance. GERD may also be associated with chronic cough, asthma, pharyngitis, stomatitis and sleep disorder[12]. In the present study, the incidence of GERD in Han was higher than that found in several previous reports[3,4], and was possibly due to environmental differences. To date, there have been no published reports on GERD in Uygur, our findings showed that the incidence of GERD in Uygur (including NERD) was significantly higher than that in Han. In addition, the incidence of GERD in Uygur was higher than that in Israeli subjects, while the GERD ratio in females was lower than those in Israeli and Japanese females[21,22]. However, our findings were in agreement with those in previous studies carried out in Western populations, which indicated a ethnic group difference [23], further highlighting ethnic group and geographical differences.

The Gerd Q was designed by Jones et al[8] in 2007, and was used to assess and diagnose GERD, and to assess symptom changes and quality of life in GERD patients. Several studies have demonstrated its effectiveness and reliability[24]. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that when taking a score of 8 as the diagnostic threshold for GERD, the accuracy rating was up to 70%, which was close to the diagnostic level of a gastroenterologist. After comparing the diagnostic rate for GERD, we found that there was no significant difference between the normalized methods and the Gerd Q scale, thus a Gerd Q score of ≥ 8 can be used as a standard to diagnose GERD. Since more than 50% of GERD patients have NERD, it is impracticable to diagnose GERD routinely using endoscopy or 24-h esophageal pH monitoring in China. Therefore, in the case of a young or middle-aged patient intolerant of invasive examination who has typical reflux symptoms, but no warning symptoms, a diagnostic method based on symptoms may be desirable. We suggest that the Gerd Q scale may be used as a primary clinical diagnostic approach[25,26].

The backward method of logistic regression analysis revealed that gender, occupation, strong tea, alcohol drinking, mainly meat and BMI were the six common related risk factors in Uygur and Han adults with GERD; for Uygur adults with GERD, smoking was a related risk factor which was different from that in Han, and for Han, age was a related risk factor which was different from that in Uygur. Furthermore, all factors correlated with GERD in a linear manner. Because the age of 75% of the participants in this investigation ranged from 35 to 45 years, we did not analyze the relationship between age stratification and GERD, however, the results revealed a gender difference (Table 4). Gender, smoking and alcohol drinking have been demonstrated to be risk factors for GERD[12]. Smoking was not shown to correlate with GERD in Han participants. The smoking ratio which was lower in Han than in Uygur and racial difference were the main risk factors, in addition to occupation related to GERD in Han. This may have been due to the nature of work, lifestyle, and less exercise in Han. The above results confirmed the correlation between these risk factors and GERD. We suggest that males and civil servants are susceptible to GERD. A recent study demonstrated that gender was a related factor for GERD in Japan[27], and our results are consistent with these findings.

Xinjiang is located in Northwest China, and is a multi-ethnic area, where the day is longer than the night, and cold and dry conditions are the main climatic features which are different from those inland, and dinner-to-bed time is shorter than that inland. A recent report indicated that shorter dinner-to-bed time was significantly associated with an increased OR for GERD[28]. Uygur is the main minority group in Urumqi, and the ethnic culture, religion, lifestyle and dietary customs are different from those in Han, as mainly meat (beef and lamb) and dairy products are important dietary components. Han Chinese who live in the same region have many similarities to Uygur subjects with the exception of differences such as meat and milky tea (milky tea is a conventional drink in Uygur). The dietary structure of residents in Xinjiang is characterized by high caloric, high fat, spicy, strong flavors, strong tea, smoking and alcohol drinking which are more prevalent in males; in addition, changing lifestyle, obesity prevalence, as well as changing population structure have increasingly led to transition of the disease spectrum, which has become and is becoming common and an important etiology of GERD in Uygur and Han Chinese. Drinking strong tea is a common traditional custom in Uygur and Han subjects in Xinjiang, Fu-Brick tea which the Uygur drink and the various teas which the Han drink are fermentative green teas. Green tea consumption has also been shown to be negatively associated with the risk of chronic atrophic gastritis, as green tea can suppress the proliferation of Helicobacter pylori in the stomach and inhibit the progression of chronic atrophic gastritis[29]. Therefore, green tea, especially strong green tea, can increase gastric acid secretion leading to the development of GERD symptoms. Thus, we consider green tea to be a significant risk factor for GERD[10].

In conclusion, the present investigation and logistic regression analysis with regard to GERD in a large population clearly demonstrated that GERD is highly prevalent in adults living in Urumqi. The incidence of GERD in Uygur and Han adults, especially Uygur, was similar to that in Western populations. There are ethnic group and gender differences between Uygur and Han, and regional differences between China’s Xinjiang residents and other countries. Being male, smoking, alcohol drinking, strong tea, mainly meat and BMI are the main risk factors for GERD in Uygur, while being male, civil servant, alcohol drinking, strong tea, mainly meat and BMI are the main risk factors for GERD in Han. These factors have a significant impact on GERD symptoms and quality of life. Our results also demonstrated that the Gerd Q can be used to diagnose GERD and possibly allow the evaluation of clinical efficacy in GERD patients.

Based on the above results, it would be very advantageous to prevent the development of GERD and cure it by optimizing lifestyle (such as controlling weight[30], aerobic exercise, avoid overeating, appropriate sleep)[31], modifying dietary structure (low caloric intake, low fat intake, avoid strong and spicy foods, more vegetables, high cellulose, less stimulating beverages, less smoking, less alcohol drinking), and reducing foods and drugs that probably lead to a fall in lower esophageal sphincter pressure. When suffering from GERD symptoms, one should consult a doctor and undergo appropriate treatment under the guidance of the doctor.

The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is high in Western and developed countries, however, along with changing lifestyle and dietary habits, the incidence of GERD has also increased in the Asian-Pacific region in recent years, particularly in China, and the incidence in China is rising year by year. Xinjiang is located in the northwest region of China, and Uygur is the main minority group in this autonomous region. The gene for GERD in Uygur is a fusion gene of Caucasian and Mongoloid characteristics. The dietary characteristics of local residents prioritizes meat (mainly beef and lamb), cooked wheaten food, and alcohol drinking. In addition, strong food tastes are favored. To date, there have been few studies on the incidence of GERD with regard to minority groups, and based on this research background, authors designed and performed this study.

Studies show that there are geographical, and population (gender, age, ethnic group) differences in the incidence of GERD, and etiological factors include body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, esophageal hiatus hernia, and inheritance. Authors analyzed the prevalence of GERD in Urumqi, and compared the similarities and differences between Uygur and Han Chinese adults, and then identified risk factors for GERD. This investigation is fundamental for similar studies in the future.

This is a large-scale, epidemiological and cross-sectional, novel investigation focusing on gastroesophageal reflux disease in Uygur and Han subjects residing in Xinjiang, China. To date, there have only been a few reports on GERD in minority groups, and to our knowledge large-scale studies focusing on GERD in Uygur alone have not been carried out. SPSS analysis revealed the risk factors related to GERD, and the results provide further insight into the lifestyle, dietary customs and racial differences relating to GERD between Uygur and Han.

The particular lifestyle and dietary customs of Uygur prompted us to investigate the similarities and differences between Uygur and Han Chinese living in Xinjiang, China. Their results will go a long way towards research into GERD characteristics in minority groups in China. Several studies have demonstrated that, when taking a score of 8 (using GERD questionnaire, Gerd Q) as the diagnostic threshold for GERD, the accuracy rating was up to 70% which was close to the diagnostic level of a gastroenterologist. They suggest that Gerd Q may be used as a primary clinical diagnostic approach and a standard for estimating GERD.

GERD is a world-wide disease that affects the quality of life (reflux may depend only on the sphincter defect and may be caused by bile reflux). GERD reached a high level in Western countries (not only in the so-called developed). The Western life style and diet habits, including fast-food, has been introduced in China, more in the north than in south.

Peer reviewer: José Liberato Ferreira Caboclo, Professor, Rua Antônio de Godoy, 4120 São José do Rio Preto, Brazil

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Sonnenberg A. Effects of environment and lifestyle on gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2011;29:229-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kinoshita Y, Adachi K, Hongo M, Haruma K. Systematic review of the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1092-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | He J, Ma X, Zhao Y, Wang R, Yan X, Yan H, Yin P, Kang X, Fang J, Hao Y. A population-based survey of the epidemiology of symptom-defined gastroesophageal reflux disease: the Systematic Investigation of Gastrointestinal Diseases in China. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen M, Xiong L, Chen H, Xu A, He L, Hu P. Prevalence, risk factors and impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a population-based study in South China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:759-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yuen E, Romney M, Toner RW, Cobb NM, Katz PO, Spodik M, Goldfarb NI. Prevalence, knowledge and care patterns for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in United States minority populations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:645-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Stat 1. 1994;1-407. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE. Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92:686-693. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, Vakil N, Halling K, Wernersson B, Lind T. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030-1038. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1653] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8 Suppl 1:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chua CS, Lin YM, Yu FC, Hsu YH, Chen JH, Yang KC, Shih CH. Metabolic risk factors associated with erosive esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1375-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee SW, Lien HC, Chang CS, Peng YC, Ko CW, Chou MC. Impact of body mass index and gender on quality of life in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5090-5095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choi CW, Kim GH, Song CS, Wang SG, Lee BJ, I H, Kang DH, Song GA. Is obesity associated with gastropharyngeal reflux disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:265-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vega KJ, Chisholm S, Jamal MM. Comparison of reflux esophagitis and its complications between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2878-2881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lan JC, Zhou HY, Bai XH, Chen XP, Xing YZ. [Investigation of the characteristics of Rh blood group of Uygur nationality in Xinjiang]. Zhongguo Shiyan Xueyexue Zazhi. 2007;15:885-887. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Zhou HY, Bai XH, Zhang YZ, Wang CR, Cao Q, Lan JC. [A comparative research on RHD gene structures of Chinese Han and Uigur population]. Zhonghua Yixue Yichuanxue Zazhi. 2006;23:151-155. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ghoshal UC, Chourasia D. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chourasia D, Achyut BR, Tripathi S, Mittal B, Mittal RD, Ghoshal UC. Genotypic and functional roles of IL-1B and IL-1RN on the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the presence of IL-1B-511*T/IL-1RN*1 (T1) haplotype may protect against the disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2704-2713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sharma P, Wani S, Romero Y, Johnson D, Hamilton F. Racial and geographic issues in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2669-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moshkowitz M, Horowitz N, Halpern Z, Santo E. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: prevalence, sociodemographics and treatment patterns in the adult Israeli population. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1332-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Murao T, Sakurai K, Mihara S, Marubayashi T, Murakami Y, Sasaki Y. Lifestyle change influences on GERD in Japan: a study of participants in a health examination program. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2857-2864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sperber AD, Halpern Z, Shvartzman P, Friger M, Freud T, Neville A, Fich A. Prevalence of GERD symptoms in a representative Israeli adult population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Della Casa D, Missale G, Cestari R. [GerdQ: tool for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in primary care]. Recenti Prog Med. 2010;101:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kriengkirakul C, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. The Therapeutic and Diagnostic Value of 2-week High Dose Proton Pump Inhibitor Treatment in Overlapping Non-erosive Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Functional Dyspepsia Patients. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:174-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jonasson C, Moum B, Bang C, Andersen KR, Hatlebakk JG. Randomised clinical trial: a comparison between a GerdQ-based algorithm and an endoscopy-based approach for the diagnosis and initial treatment of GERD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1290-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, Kobayashi S, Ariizumi K, Abe Y, Iijima K, Imatani A, Inomata Y, Kato K. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a large unselected general population in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1358-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fujiwara Y, Machida A, Watanabe Y, Shiba M, Tominaga K, Watanabe T, Oshitani N, Higuchi K, Arakawa T. Association between dinner-to-bed time and gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2633-2636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ruggiero P, Rossi G, Tombola F, Pancotto L, Lauretti L, Del Giudice G, Zoratti M. Red wine and green tea reduce H pylori- or VacA-induced gastritis in a mouse model. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:349-354. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Singh M, Lee J, Gupta N, Gaddam S, Smith B, Wani S, Sullivan D, Rastogi A, Bansal A, Donnelly J. Weight Loss Can Lead to Resolution of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms: A Prospective Intervention Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;Jun 25; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Di Biase AR, Colecchia A. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1690-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |