INTRODUCTION

With the many recent advances in the general area of liver regenerative medicine, there have been a multitude of significant improvements regarding the technology of liver bioengineering and regeneration. The purpose of the present review is to illustrate the two main strategies that are currently being implemented to manufacture liver organoids for clinical purposes.

DECELLULARIZATION-RECELLULARIZATION TECHNOLOGY

Several studies have provided evidence that this technology offers a valuable platform for liver bioengineering through the repopulation of an acellular liver with appropriate fresh cells.

The first report addressed the methodology for the decellularization of rodent livers[1]. Livers were cannulated through the inferior vena cava, with the portal vein severed and the superior vena cava clamped. The decellularization process began with rinsing of the liver with 100 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to clear the blood followed by perfusion of three 300 mL isotonic solutions of 1%, 2%, and 3% Triton X-100 at a rate of 5 mL/min. This was followed by perfusion of a 300 mL PBS solution containing 0.1% sodium monododecyl sulfate (SDS) and a 300 mL PBS wash. The disruption of the lipid membranes cleared most of the cellular components of the organ except for intact nuclear cages containing DNA, which was further removed by a solution of SDS. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the intact decellularized liver showed a fine web of matrix remaining in the acellularized liver, which was further analyzed by immunohistochemical staining of collagen IV and laminin. The stains showed the presence of collagen within the matrix and that laminin was present within the basement membrane of the vessels. After the decellularization process, the scaffold remained intact and strong enough to maintain further cannulation for the perfusion of cells. 106 cells of the rat liver progenitor cell line WB344 in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium were infused into the decellularized liver through the cannulated inferior vena cava. Further histological analysis of the center of the intact recellularized scaffold indicated that the intrahepatic vasculature was able to traffic cells from the inferior vena cava. This report demonstrated the necessary process of using SDS in the decellularization process to truly remove any cellular components, specifically DNA.

Another similar subsequent report that used a similar decellularization method showed vascular patency through portal vein dye[2]. The decellularization process was performed by sequential perfusion of different concentrations of detergents through the portal vein at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The livers were perfused for 72 h with SDS in distilled H2O: 0.01% SDS for 24 h, 0.1% SDS for 24 h, and 1% SDS for 24 h. The livers were then perfused with distilled H2O for 15 min and with 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min to cleanse the livers of any remaining SDS. After rinsing the decellularized livers with PBS for 1 h, only the median lobe was sterilized in 0.1% peracetic acid in PBS for 3 h and kept for recellularization after further extensive PBS washing. The decellularized scaffolds were histologically analyzed to demonstrate that the scaffolds were acellular and functionally similar to an intact normal liver, in order for recellularization to be possible. Histological analysis showed that there were no nuclei or cytoplasmic staining in the decellularized liver compared to a normal rat liver. Immunohistochemical analysis of four extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (collagen type I, collagen type IV, fibronectin and laminin-β1) showed that the structural and basement membrane components of ECM remained intact similarly to the normal liver. DNA analysis of the decellularized scaffold showed that less than 3% of residual DNA remained after the decellularization process. They also reported intact functional vascular beds and microvasculature through the perfusion of the Allura Red dye. The dye flowed through the vasculature just as expected in a functioning liver. The acellular translucent scaffold was then infused with rat-derived hepatocytes through perfusion of the portal vein at 15 mL/min. The perfusion system consisted of a peristaltic pump, bubble trap, and oxygenator from a donors-after-cardiac-death organ resuscitation perfusion system. They introduced approximately 12.5 million cells during each of the four steps in ten-minute intervals, which showed superior engraftment efficiency when compared to a single-step infusion. The recellularized grafts were maintained in a perfusion chamber for up to 2 wk in vitro, with histological staining of the recellularized sections at 4 h, 1 d, 2 d, and 5 d of perfusion. At 4 h, the majority of the cells remained in and around the vessels; however, at 1 d and 2 d, the cells leave the vessels and become distributed throughout the matrix.

It should be emphasized that this is the first report that contains data showing the level of function exhibited by the hepatocytes grown on the decellularized matrix. They report that hepatocyte viability was maintained during culture and that cell death was kept to a minimum. They were also able to determine that the cells migrated beyond the matrix barrier to reach decellularized sinusoidal spaces through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and histological analysis. They also determined that albumin synthesis was not increased in the recellularized matrix compared to an intact liver; however, urea synthesis was significantly higher in the recellularized liver than the hepatocyte sandwich during culture. The analysis of the expression of drug metabolism enzymes showed that the levels of Cyp2c11, Gstm2, Ugt1a1, and Cyp1a1 that were expressed in the recellularized grafts were similar to those of the sandwich hepatocyte cultures. The recellularized liver grafts were then transplanted into recipient rats that underwent unilateral nephrectomy for auxiliary liver graft transplantation. The recellularized liver grafts were perfused quickly with blood and the appropriate efflux occurred only after 5 min. The graft was maintained in vivo for 8 h, and then harvested for further Tdt-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling staining analysis. This staining demonstrated that the cells were minimally damaged and further histological staining showed that the hepatocytes reserved normal morphology and parenchymal positions.

While it is extremely important to have these previous promising reports on liver decellularization and recellularization, the ultimate necessary technology that needs to be expanded upon is the decellularization and recellularization of whole organs-specifically human organs, and subsequently human derived cell lines-in order to create a transplant graft for possible human functioning. The report by Baptista et al[3] demonstrated the potential for the colonization of human hepatocyte progenitors on a decellularized liver matrix. This is one of the first reports to show the decellularization and recellularization process with a whole liver instead of thin slices or lobes of the liver, as well as the first report to recellularize successfully with human liver cells. They attempted to decellularize whole livers from multiple species as well, including mice, rats, ferrets, rabbits, and adult pigs.

All of the dissected livers were cannulated with different gauged cannulas, depending on the species, through the inferior vena cava and the portal vein, which were then hooked up to a Masterflex peristaltic pump in preparation for decellularization. There was approximately 40 times the volume of the liver perfused with distilled water at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The decellularization process was performed by perfusion of approximately 50 times the volume of the liver with 1% Triton-X 100/0.1% Ammonium Hydroxide. The approximate perfusion times for the decellularization process were 1 h for mice, 2 h for ferret, 3 h for rat, and 24 h for pig livers. It was visibly clear after the perfusion period that the parenchyma became transparent and the vascular tree was visible under low magnification microscopy (Figure 1).

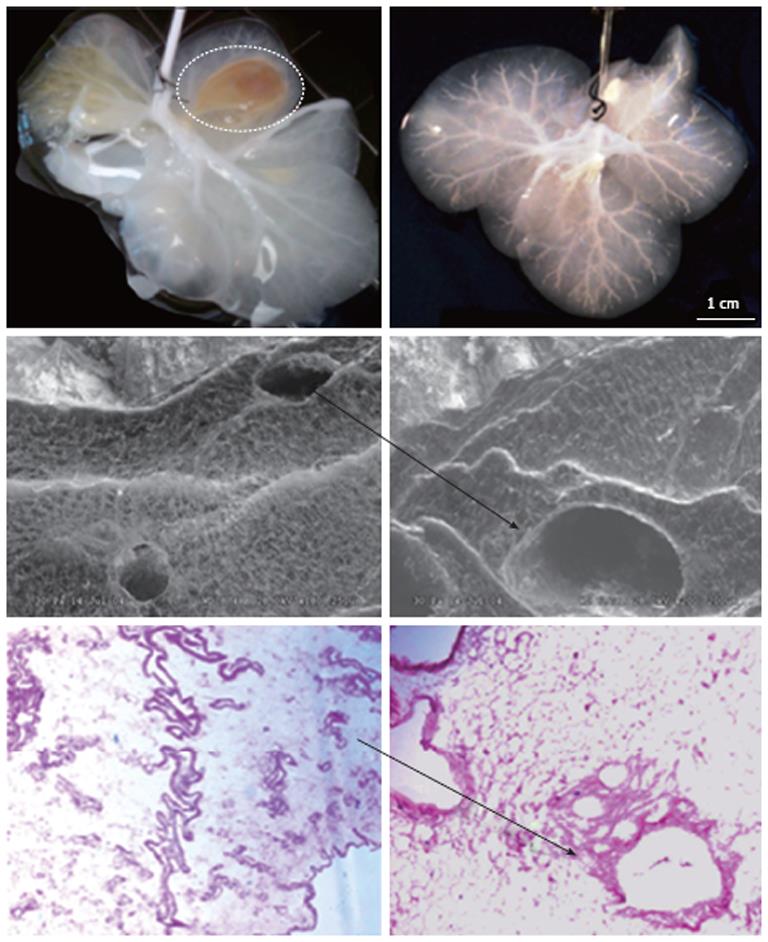

Figure 1 Gross and microscopic anatomy of acellular ferret livers.

Upper row: The liver on the left is almost entirely decellularized, however it remains a segment still cellular (interrupted line); on the left, instead, the liver is fully acellular as expression of successful decellularization; Middle row: Scanning electronic microscopic ruling out the presence of any cell remnant and showing the triad completely acellular (arrow); Lower row: Hematoxylin and eosin confirms the lack of cellular element within the remaining liver extracellular matrix (arrow).

Spectrophotometric and agarose gel DNA analysis showed the removal of approximately 97% of the DNA from the tissue, indicating efficiency of the decellularization process. SEM was performed to determine that that ultrastructure was preserved. The SEM analysis showed that reticular collagen fibers that support the hepatic tissue were present and the “portal triad” structures remained intact, as well as the lack of any cells. Histological analysis of acellular ECM was performed to further characterize the scaffold composition. The staining showed that there was no cellular nuclear material or any other cellular material present. The staining also showed that collagen layers with vascular channels were present, along with collagen fibers, elastin fibers, and glycosaminoglycans (Figure 2).

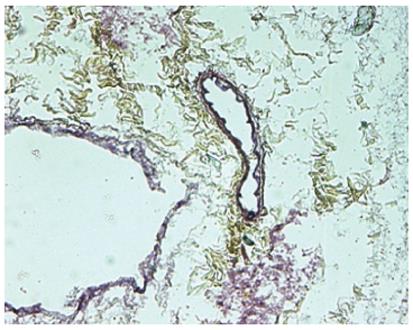

Figure 2 Movat-Pentachrome staining of acellular liver sections shows yellow staining for collagen and dark staining for elastin surrounding the vascular structures.

Quantification of the ECM components showed higher levels of collagen and glycosaminoglycans in the decellularized scaffold compared to native tissue, which can be explained by the absence of cellular components, while there was no difference in elastin presence. The localization of the specific extracellular matrix proteins collagen I, collagen III, collagen IV, laminin, and fibronectin were all observed around the vascular structures, specifically denser around the larger vessels, and the parenchymal areas of the acellular liver, as well as the fresh tissue. Vascular preservation and patency was demonstrated by the ability of the network of vascular remnants to retain labeled dextran that had a similar molecular weight to that of blood proteins.

The recellularization methods used in this report show that perfusion through the vena cava or the portal vein (preferred) both allow the green fluorescent protein-labeled MS1 endothelial cells to line the vascular network, including the larger vessels to the capillary sized vessels. Portal vein-seeded endothelial cells were primarily deposited in the periportal regions of the liver lobule while the vena cava-seeded endothelial cells were primarily concentrated in the regions of the central veins and in smaller branches and vessels. Through fluorescent microscopy and transmission electron microscopy they were able to determine that the lumens of the acellular vascular remnants could be colonized by endothelial cells that were able to actively spread and cover the vessel basement membrane while forming appropriate cell-cell junctions. They also determined that the surface of the vascular lumen was non-thrombogenic, which was confirmed by the lower quantification of platelets in the bioscaffold compared to the fresh tissue. The reseeding experiments performed in this report utilized the coseeding of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and freshly isolated human fetal liver cell’s, while using similar recellularization protocols previously mentioned. Immunohistochemical analysis was used to assess the proliferation and analyze the presence of hepatocytic lineage markers. Staining of Ki67 to assess proliferation showed a high number of positive cells throughout the bioscaffold, which was 3 times higher than the number of apoptotic cells present. The staining also showed that the hepatocytic markers α-fetoprotein, CYP2A, and CYP3A were expressed in the parenchyma. Cytokeratin 19 was strongly seen throughout the bioscaffold in biliary tubular structures while clusters of albumin-expressing hepatocytes were distributed in the parenchyma. The small amount of coexpression of these specific markers implies that there are specific niches within the bioscaffold for bile duct and hepatocytes. Immunohistochemical staining also detected CK19+/CK18-/ALB-tubular structures and clusters of ALB+/CK18+ cells in the parenchyma, which suggests that the bioscaffold is able to support the differentiation of the fetal hepatoblasts into biliary or hepatocytic lineages. The ability of cells with immunophenotypes consistent with hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, and endothelial cells to form discrete pockets in the bioscaffold suggests that some of the micro-architectural “blueprint” was retained within the scaffold. This suggests that not only does the bioscaffold provide a three-dimensional vascularized scaffold (previously described) but it also retains the necessary environmental cues, further explained by the retention of the glucosaminoglycans that serve as active binding sites for growth factors that regulate cell phenotype, for progenitor hepatic and endothelial cells to grow, differentiate, and maintain functionality.

A related study reports on a refined decellularization procedure. This study demonstrated the ability of liver progenitor cells to differentiate to both the hepatocyte and cholangiocyte lineages while seeded on the decellularized scaffold[4]. The strategy for recellularizing the bioscaffold was aimed at creating a more rapid and efficient differentiation of the stem cells using tissue-specific extracts enriched in extracellular matrix and a hormonally specific defined medium using associated growth factors and cytokines. They reseeded the scaffold with human hepatic stem cells in a hormonally defined medium specific for adult liver cells. The stem cell markers were expressed in the cells after the reseeding process and the cells differentiated into mature functional parenchymal cells in approximately one week. These cells remained viable and presented stable mature phenotypes for more than 8 wk.

Similar results have been obtained by other groups[5,6]; however in all the above reported investigations liver ECM was produced from rodent livers. Instead, Barakat et al[7] recently developed a method to decellularize porcine livers, which were eventually repopulated with human cells[8,9]. The goal was to produce a clinically relevant model of liver bioengineering. Livers from Yorkshire pigs were decellularized with SDS. The ECM of the posterior segment of the right liver lobe was used as scaffold for cell seeding. Fetal hepatocytes co-cultured with fetal stellate cells were expanded, collected, resuspended in appropriate medium supplemented with hepatocyte growth factor and seeded within the ECM. The so-obtained constructs were perfused for 3 d, 7 d and 13 d. During perfusion, pH, PO2, PCO2, lactate, glucose, urea nitrogen and albumin were measured to assess metabolic and synthetic functions. Of note, some constructs were implanted in vivo and perfused for 2 h to determine the behavior of the matrix in vivo and its ability to withstand the shear stress produce by the blood flow in physiologic conditions. Results were encouraging. Liver organoids showed active metabolism and preserved capability to synthesize albumin, and were able to sustain blood pressure without harm. Notably, immunohistochemical analysis revealed cell differentiation into mature hepatocytes. This latter finding provides evidence that ECM is essential in that it supports cells and may drive the differentiation of progenitor cells into an organ-specific phenotype[10]. Badylak’s group confirmed this information in an elegant model of liver hepatectomy in rats[11], in which he demonstrated that liver ECM implanted in intact and amputated livers enhances hepatocyte proliferation and ultimately liver regeneration.

While the primary goal for the majority of the research pertaining to decellularizing and recellularizing an organ is the functional transplantation of a bioengineered organ into a recipient host, there are the possibilities of using this technology in in vitro studies for advanced preclinical drug development[12]. This report provided a 60-min rapid natural decellularization method for a 3-dimensional scaffold prepared from a rat liver that maintained the microvascular system and was able to withstand fluid flowing through all three hepatic circular systems. The method utilized two thirty-minute perfusion periods; a 1% Triton-X 100 solution followed by a 1% SDS solution. The development of a novel in vitro 3-dimensional model that closely represents the in vivo liver could present the potential for toxicity testing of key compounds in preclinical drug developments since the liver is the main metabolizing organ that is usually the target of toxicity.

CELLS FOR LIVER REGENERATION

The liver is able to regenerate itself with the ability to maintain adequate volume and function after undergoing up to 70% resection. However, the way the liver regenerates after a more or less extended amputation is not a true recapitulation of liver ontogenesis. In fact, resumption of the original volume is accomplished by cellular hyperplasia of the remaining liver rather than true regeneration of the amputated portion whose original anatomy will not be resumed[13]. Therefore, from an evolutionary perspective, liver hyperplasia is a mechanism of repair that has developed to restore normal function, not normal anatomy. Unfortunately, the actual system that regulates the hepatic regeneration after injury remains mostly obscure. When the liver regenerates after amputation, cellular hyperplasia occurs spontaneously through a complex cascade of events and pathways. This cascade of regulation involves the inflammatory signaling, the recruitment of inflammatory cells, the stimulation of hepatobiliary cell proliferation, and the ultimate aim of cell migration and neo-angiogenesis. The restoration of the tissue mass is thus carried out by the division of mature hepatocytes. If the mature hepatocytes are unable to maintain sufficient proliferative potential to restore the organ, or if there is complete inhibition of this process, intervention occurs from the liver progenitor cells, known as oval cells[14-18].

There are many techniques that address regenerating the liver, without actually fully regenerating and replacing the organ, by attempting to enhance the natural regeneration of the injured liver. The basic idea behind this technique is to enhance the liver’s natural ability to regenerate itself through the transplantation and mobilization of liver progenitor cells that are isolated from bone marrow. The studies that address this technique base the idea off the fact that it has been found that the cells resident to the bone marrow are able to aid in liver regeneration by differentiating into fully functional hepatocytes[19-22]. While these studies have yet to fully characterize these cells, it has been clearly established that there are bone marrow populations that could have the ability to increase the quality of the clinical conditions regarding patients that have chronic liver disease or injury. In these clinical trials the initial goal was to determine whether or not the infusion of autologous bone marrow cells, through perfusion of the peripheral vein or the hepatic artery, into patients who have liver cirrhosis, was safe. Some of these studies were able to achieve more than just safety results, and showed that there was statistically significant clinical improvement in the patients[23-25].

More recent studies have attempted to determine the clinical safety of administering patients with the hematopoietic stem cell mobilizing cytokine, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), which has been shown to improve the functioning of the liver in patients with liver disease. It is thought that the function of the G-CSF is to primarily activate cells that are within the bone marrow that have hepatocyte lineage differentiation potential. G-CSF not only interacts with the bone marrow cells, but it has also been shown to increase the ability of resident progenitor cells that have the receptor for the cytokine to respond to injuries. In these studies it has been determined that the G-CSF is able to maintain the ability to mobilize cells from the bone marrow and the peripheral circulation, while there is an increase in the circulating hepatocyte growth factor that plays a major role in liver regeneration[26-29]. The bone marrow and peripheral blood are great sources for this because they are easily accessible while having a large source of stem cells and progenitor cells that are able to proliferate in vitro. Since these studies primarily aimed to focus on the safety potential for administering the cytokine, there have been two large studies that have been conducted in order to actually determine the therapeutic treatment potential of this technique. These trials were performed by administering G-CSF to the patient with liver disease, which was then followed by the isolation of stem cells from both the peripheral circulation and the bone marrow. These isolated cells were then infused back into the patient through the already established perfusion methods. The trials clearly showed significant improvement in the serum bilirubin and the liver enzyme levels, while there was no improvement noticed in the untreated control group[30,31].

As previously mentioned, despite the clearly seen therapeutic potential for bone marrow cells to help the regenerative process of a diseased liver, the findings from these trials have yet to be able to determine the specific cell in the bone marrow that is actually aiding in the regeneration. There have been a few in vivo animal models that have demonstrated the ability for bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+/Lin-) to have ability to differentiate into hepatocytes[32-36]. Fetal liver progenitor cells have also been shown to improve the condition of cirrhotic patients[37,38]. Therefore, the use of these cells with the previously described isolation and infusion techniques presents multiple advantages for creating a potential therapy. This presents the possibility of having an easily obtainable source of cells that are from the isolated G-CSF mobilized bone marrow cells. The concern of the patient having a rejection to the treatment would be absent because all of the cells used in the therapy are autologous. A portion of these cells used could also possibly carry a progenitor phenotype following infusion, which could help participate in the liver repopulation over time when the damage to the native hepatocyte population is chronic. The corrective gene could therefore be slowly increased in the native cells with as little as a repopulation of 10% of the cells expressing the factor[39].

Other cell sources are also available, namely fetal hepatoblasts and stem cells from adult or fetal tissue. As reported above, Baptista et al[3] used fetal liver hepatoblasts to recellularize liver ECM scaffolds. Once in this three-dimensional environment, these liver progenitors were able to expand and differentiate into biliary and hepatocytic lineages. In the fetal liver, these cells are the main parenchymal cell type and are identified by their expression of α-fetoprotein (AFP). These cells are rare in the normal adult liver, except in livers with severe injury or disease[40,41]. Because these cells are able to originate the two hepatic cell lineages, hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, they are named bipotential progenitors.

AFP-negative hepatic stem cells are the precursors to hepatoblasts that can mature into AFP-positive hepatoblasts[42-44]. Human fetal hepatoblasts are then the putative transient amplifying progenitors in the liver lineage and can be cultured long-term and clonally, contributing to liver parenchyma when transplanted into SCID mice[45]. Hepatoblasts express biliary and hepatocyte markers such as CK19, CK14, α-GT, glucose-6-phosphatase, glycogen, albumin, AFP, E-cadherin[46], α-1 microglobulin, HepPar1, glutamate dehydrogenase, and DPP-IV[42,47]. These progenitors do not express mesenchymal or hematopoietic markers like CD90, vimentin, and CD34[46]. The therapeutic potential and safety of these cells has already been successfully tested in human patients with end-stage chronic liver disease[48]. In these patients, there was significant clinical improvement in terms of biochemical and overall clinical parameters. Moreover, mean MELD score decreased (P < 0.01) over the following 6 mo after stem cell therapy. Thus, fetal derived stem/progenitor cells have the potential to provide supportive therapy to organ transplantation in the management of end-stage liver diseases[18,48-54].

This notwithstanding, it is the authors’ conviction that cell transplantation alone may not be appropriate. In fact, clinical transplantation provides incontrovertible evidence that the outcome of cell transplantation is very poor when compared to whole organ transplantation. Therefore, it cannot be proposed as an alternative to whole organ transplantation, rather it should be considered still an experimental treatment, as it has been proposed by Cravedi’s[55] in the case of islet transplantation and by from a regenerative medicine perspective, the poor outcome may be attributed to the fact that cells welfare is dramatically impaired when cells are extrapolated by their natural niche-namely the ECM-despite encapsulation. Therefore, research should direct efforts to bioengineer a suitable supporting scaffold, which would recapitulate the same characteristics of the natural environment.

Interestingly, some authors have proposed a different bioengineering method, which does not require any supporting scaffolds. However, cells are not manipulated alone but are grown in order to produce cell sheets. Haraguchi’s group[56] employs temperature-responsive culture surfaces onto which poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) is covalently immobilized to control cell adhesion/detachment with simple temperature change. Cells adhere, spread, and proliferate on temperature-responsive surfaces at 37 °C, which is the normal temperature for mammalian cell culture. By reducing temperature below 32 °C, cells spontaneously detach from the surfaces without requiring proteolytic enzyme such as trypsin, since the grafted polymer becomes hydrophilic. When temperature is reduced after cells reach confluency, all the cells are harvested as a single contiguous cell sheet. The advantage of this method is that, as trypsin is not used, all cell membrane proteins including growth factor receptors, ion channels, and cell-to-cell junction proteins are intact after the harvest. Furthermore, the ECM deposited during cell culture is retained under cell sheets, and therefore, cell sheets easily integrate to transplanted sites. In a murine model, sheets of hepatic tissue transplanted into the subcutaneous space resulted in efficient engraftment to the surrounding cells, with the formation of two-dimensional hepatic tissues that stably persisted for more than 6 mo, while showing several liver-specific functions[57].

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The need for improved treatment modalities for patients with diseased or absent tissues or organs is evident. Regenerative medicine holds the promise of regenerating tissues and organs by either stimulating previously irreparable tissues to heal themselves, or manufacturing them ex vivo[58-64]. In the first scenario, cells with regenerative potential are targeted to the diseased bodily district. Given the multitude of available sources of these cells, it is still a mystery as to which are the most appropriate and best cell sources. Although this may vary depending on the tissue or organ of interest, it is important to fully understand the biological mechanisms controlling differentiation along a specific lineage of all cell types. Ideally, it is desirable to have the ability to harvest autologous cells and employ them with minimal ex vivo manipulation. Ultimately, the goal is to identify cells that can be easily harvested and differentiated consistently along the lineage of interest. At the same time, research should aim to in-depth understanding of all environmental stimuli that are required by liver SC niches to be activated and allow hepatocyte and/or biliocyte regeneration aiming to compensate tissue loss.

In the second scenario, differentiated, adult liver cells or SC are seeded on supporting scaffolds and allowed to mature in custom-made bioreactors. Human or animal-derived whole tissue ECM scaffolds are preferred, compared to artificial homogeneous materials, because they preserve an intact vascular network that will allow regeneration of the vascular system for optimal delivery of nutrients and oxygen. The utilization of autologous cells holds the theoretical potential to rule out immunological breakdowns and concerns, and limits the response of the immune system to a non-harmful inflammatory reaction.

In both cases, there are clearly a lot of gray areas that need to be colored in[58,59,63,65-69]. There has been a greater understanding of the cell types and numbers of cells used for repopulation, but it is still lacking the perfected elements to produce optimal results. Even when this is fully understood and developed, there also needs to be an established standard or test on the bioengineered organ that would reveal the successful incorporation of all the necessary items that the organ requires in order to be fully functional in vivo. The actual functionality of the cells within the decellularized matrix and of the organoid as a whole, as well as the biocompatibility of the so-obtained construct, absolutely must be confirmed before transplantation can ever be a feasible option. Importantly, it will be crucial to understand the mechanisms through which cells interact with the environment and in particular how the liver ECM drives and regulates cell fate and which additional molecules (namely growth factors) are essential to achieve this goal.

Peer reviewers: Masaki Nagaya, MD, PhD, Islet Transplantation and Cell Bilology, Joslin Diabetes Center, One Joslin Place, Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA 02215, United States; Susumu Ikehara, MD, PhD, Professor of First Department of Pathology, Director of Regeneration Research Center for Intractable Diseases, Director of Center for Cancer Therapy, Kansai Medical University, 10-15 Fumizono-cho, Moriguchi City, Osaka 570-8506, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN