Published online Sep 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.5106

Revised: May 8, 2012

Accepted: May 13, 2012

Published online: September 28, 2012

AIM: To evaluate quality of life (QOL) following Ivor Lewis, left transthoracic, and combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

METHODS: Ninety patients with esophageal cancer were assigned to Ivor Lewis (n = 30), combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic (n = 30), and left transthoracic (n = 30) esophagectomy groups. The QOL-core 30 questionnaire and the supplemental QOL-esophageal module 18 questionnaire for patients with esophageal cancer, both developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, were used to evaluate patients’ QOL from 1 wk before to 24 wk after surgery.

RESULTS: A total of 324 questionnaires were collected from 90 patients; 36 postoperative questionnaires were not completed because patients could not be contacted for follow-up visits. QOL declined markedly in all patients at 1 wk postoperatively: preoperative and 1-wk postoperative global QOL scores in the Ivor Lewis, combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic, and left transthoracic groups were 80.8 ± 9.3 vs 32.0 ± 16.1 (P < 0.001), 81.1 ± 9.0 vs 53.3 ± 11.5 (P < 0.001), and 83.6 ± 11.2 vs 46.4 ± 11.3 (P < 0.001), respectively. Thereafter, QOL recovered gradually in all patients. Patients who underwent Ivor Lewis esophagectomy showed the most pronounced decline in QOL; global scores were lower in this group than in the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic (P < 0.001) and left transthoracic (P < 0.001) groups at 1 wk postoperatively and was not restored to the preoperative level at 24 wk postoperatively. QOL declined least in patients undergoing combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy, and most indices had recovered to preoperative levels at 24 wk postoperatively. In the Ivor Lewis and combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic groups, pain and physical function scores were 78.9 ± 18.5 vs 57.8 ± 19.9 (P < 0.001) and 59.3 ± 16.1 vs 70.2 ± 19.2 (P = 0.02), respectively, at 1 wk postoperatively and 26.1 ± 28.6 vs 9.5 ± 15.6 (P = 0.007) and 88.4 ± 10.5 vs 95.8 ± 7.3 (P = 0.003), respectively, at 24 wk postoperatively. Scores in the left transthoracic esophagectomy group fell between those of the other two groups.

CONCLUSION: Compared with Ivor Lewis and left transthoracic esophagectomies, combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy enables higher postoperative QOL, making it a preferable surgical approach for esophageal cancer.

- Citation: Zeng J, Liu JS. Quality of life after three kinds of esophagectomy for cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(36): 5106-5113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i36/5106.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.5106

China has the highest incidence (13/0.1 million) of esophageal cancer worldwide. Surgery is often the main treatment modality for patients with resectable esophageal cancer because it is potentially curative in up to 40% of cases[1-3]. However, conventional radical surgeries incur a large amount of trauma and result in poor postoperative quality of life (QOL)[4-7]. Recently developed minimally invasive surgical treatments for esophageal cancer, such as laparoscopic surgery, may improve patients’ postoperative QOL. We compared postoperative QOL in patients with esophageal cancer who underwent combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy, conventional Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, or single-incision esophagectomy through the left thorax in our hospital in 2010.

Participants were selected from a group of 90 patients (62 male, 28 female; aged 46-81 years) treated by the same surgical team under the direction of Jinshi Liu to avoid bias. Inclusion criteria were: patients with resectable esophageal cancer who underwent surgical resection in our hospital between January and December 2010. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma in all patients. Patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study sample. No participant had received radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery, and no tumor showed significant invasion or distant metastasis.

This clinical trial was registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry website (No. ChiCTR-TRC-12001861). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

The patients were prospectively assigned to one of three surgical treatment groups of 30 patients each based on their order of presentation: Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy, or left transthoracic esophagectomy (Table 1). We performed bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy in patients with middle thoracic cancer in the Ivor Lewis and combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy groups because of the survival benefits associated with this procedure[8]. Cervical lymphadenectomy could not be performed in patients undergoing left transthoracic esophagectomy. During the execution of the study, two surgeries had to be converted to open operations because the huge tumor compressed the left principal bronchus, and another case was converted because of extensive pleural adhesion. To avoid bias, we excluded these three patients from the study sample and recruited additional participants to maintain a sample size of 30 patients per group.

| Esophagectomy type | |||

| Left transthoracic | Ivor Lewis | Combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic | |

| Clinical data | |||

| Patients (n) | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 20 | 19 | 21 |

| Female | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Mean age (yr) | 62.6 ± 8.4 | 58.4 ± 10.4 | 66.2 ± 9.8 |

| Average tumor length (cm) | 4.2 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| Intrathoracic anastomoses (n) | 30 | 22 | 0 |

| Left cervical anastomoses (n) | 0 | 8 | 30 |

| Clinical staging | |||

| I | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| II | 11 | 9 | 13 |

| III | 16 | 19 | 17 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intra- and postoperative variables | |||

| Operation time (min) | 143 ± 23 | 287 ± 49 | 306 ± 67 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 210 ± 97 | 245 ± 46 | 276 ± 89 |

| Postoperative complications (n) | |||

| Anastomotic fistula | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Chylothorax | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Incision infection | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy: General anesthesia was administered to each patient with a double lumen tube. The patient was then placed in the left recumbent position, and a thoracoscope camera port was placed at the midaxillary line of the 7th intercostal space. The camera was inserted, and the location of the work port was adjusted under its guidance. In general, the posterior 7th intercostal axillary line and 5th intercostal infrascapular line were selected as main work ports, and the anterior 4th intercostal axillary line as a secondary work port. The intrathoracic esophagus was mobilized while taking care not to damage the bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve and trachea, and the intrathoracic lymph node was dissected. The patient was then placed in a supine position and the stomach was mobilized under camera guidance. The main work port was generally located 1 cm below the costal arch at the midclavicular line on the right abdominal wall, and the secondary work port was located 40% along a line extending from the navel to the main work port. On the left side, the port was located 1 cm below the left costal arch at the anterior axillary line. After mobilization of the stomach and dissection of the celiac lymph node, a approximately 5-cm-long incision was made in the abdominal wall, the cardia and proximal stomach were lifted manually, and a linear cutter was used to construct a gastric tube. The gastric tube was then returned to the abdomen. Finally, anastomosis was performed at the left cervix with a stapler. If indicated, a bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy was performed.

Left transthoracic esophagectomy: Anesthesia was the same as for combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy. The patient was placed in the right lateral position and the chest was entered at the 6th or 7th intercostal space according to the disease focus. The diaphragm was opened, the stomach was isolated, and a gastric tube was made. The intrathoracic esophagus was mobilized and local lymph nodes were cleared. Anastomosis was performed above or below the costal arch with a stapler.

Ivor Lewis esophagectomy: Anesthesia was the same as for combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy. The patient was placed in a supine position and the abdomen was opened. The stomach was mobilized, a gastric tube was made, the celiac lymph node was dissected, and the abdomen was closed. The patient was then placed in a left recumbent position and the chest was entered through the 5th intercostal space. The intrathoracic esophagus was mobilized and local lymph nodes were dissected. Finally, anastomosis was performed at the cupula pleurae or left neck, according to the disease focus. The superior margin of the cancer was located endoscopically. Patients underwent neck anastomosis if the distance between the incisor and the superior margin of cancer was less than 25 cm, and otherwise underwent intrathoracic anastomosis. A bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy was performed in cases of left cervix anastomosis.

The posterior mediastinal route was used in all patients. All patients received thoracic epidural analgesia for 3 d postoperatively.

QOL was evaluated in all patients using the quality of life-core 30 questionnaire (QLQ-C30; ver. 3.0, in Chinese) and the supplemental quality of life-esophageal module 18 questionnaire (QLQ-ES18, in Chinese) for patients with esophageal cancer, both of which were developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer (EORTC)[9,10]. For this evaluation, each patient was visited in person during hospitalization 1 wk before and 1 wk after surgery, and contacted by telephone at 12 and 24 wk postoperatively. Patients completed the self-administered questionnaires, with the assistance of their physicians and/or relatives in cases of reading or writing difficulty. These assistants explained questions to the patients and recorded responses. Because the patients fasted during the first postoperative week, food intake was not evaluated.

The QLQ-C30 (including the Chinese version) has been used in QOL studies of patients with all kinds of cancer, and has shown good reliability and validity[11,12]. This questionnaire includes a total of 30 items in five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), three general symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain), one global QOL scale, and six single-item measures of general symptoms or problems (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties). Responses to each item are structured on a four-point scale: “not at all” (scored as 1), “a little” (scored as 2), “quite a bit” (scored as 3), and “very much” (scored as 4). The global QOL scale ranges from “very poor” (scored as 1) to “excellent” (scored as 7). Higher functional and comprehensive QOL index scores indicate better functions and QOL, whereas higher symptomatic index scores indicate worse symptoms and lower QOL[13].

The QLQ-ES18 is a QLQ-C30 supplement that is applied specifically to patients with esophageal cancer. This questionnaire contains a total of 18 items assessing symptoms such as dysphagia, reflux, and coughing when swallowing. Responses to each item are structured on the same four-point scale used in the core questionnaire[10]. Blazeby et al[10] demonstrated that the QLQ-ES18 had good psychometric and clinical validity, and recommended its use in combination with the core questionnaire, the QLQ-C30, to assess QOL in patients with esophageal cancer. Numerous studies have shown that the combined use of the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-ES18 (including Chinese versions) reflects QOL objectively in patients with esophageal cancer[14-17].

Each questionnaire item score was converted linearly to a scale of 1-100 according to the EORTC scoring manual[10,12,18], and means and standard deviations were then calculated. Data were processed using the SPSS software (ver. 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and QOL indices were compared among groups using the independent-samples t test. General patient information was compared among groups using the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The three groups showed no significant difference in age, sex, average tumor length, or clinical stage.

The mean operation time for left transthoracic esophagectomy (143 ± 23 min) was shorter than those for combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy (306 ± 67 min; P < 0.01) and Ivor Lewis esophagectomy (287 ± 49 min; P < 0.01). The amount of blood loss did not differ among the three groups. One case of anastomotic leakage, one incision infection, and one chylothorax occurred postoperatively in the Ivor Lewis group. In the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy group, three cases of anastomotic leakage occurred postoperatively. No complication was found in the left transthoracic esophagectomy group (Table 1). The incidence of postoperative complications did not differ among groups, and all patients recovered completely after surgery. All patients were alive at 24 wk after surgery. No cancer recurrence or metastasis was found in any patient during the 24-wk follow-up period.

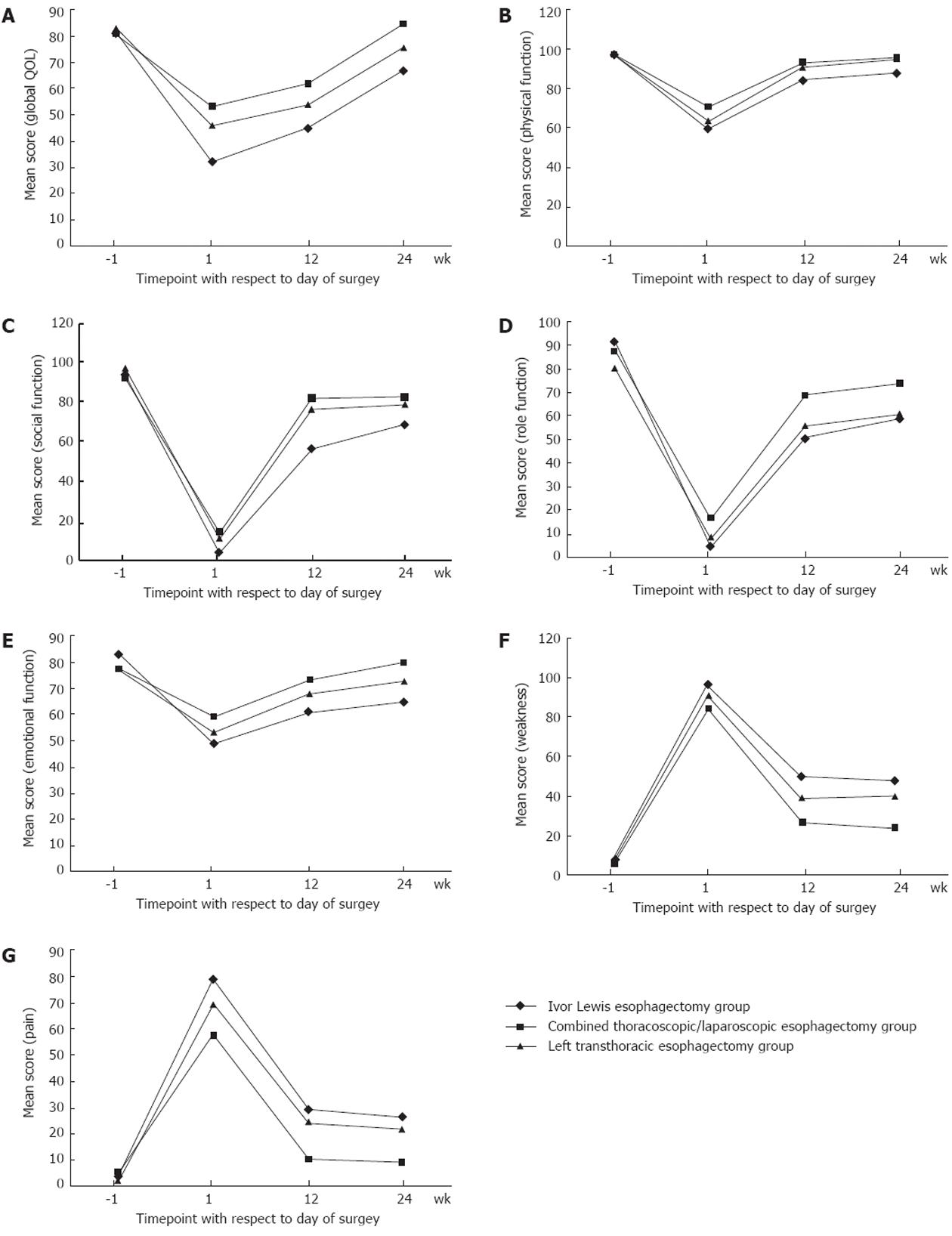

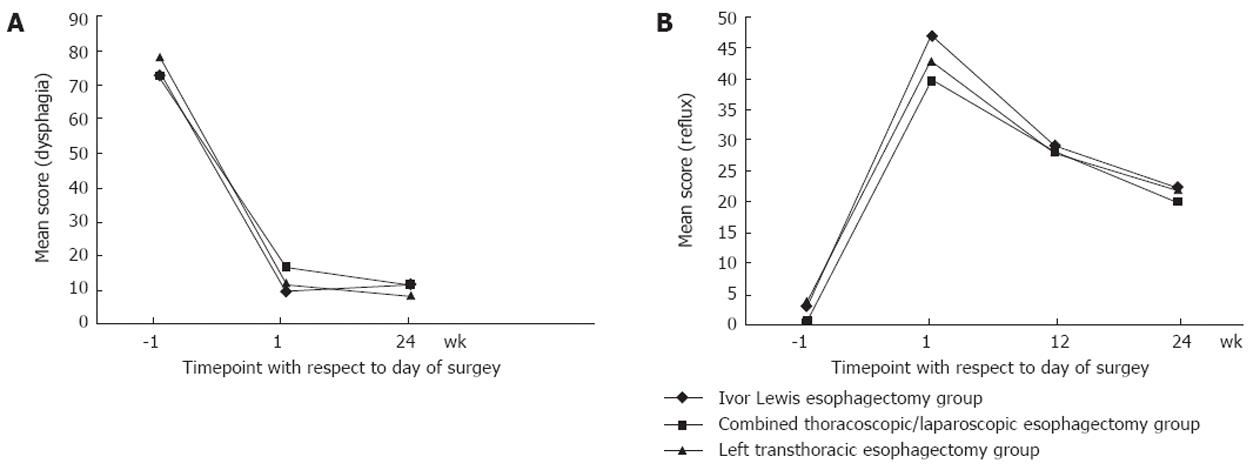

In total, 324 questionnaires were collected from 90 patients; 36 postoperative questionnaires were not completed because the patients could not be contacted for follow-up visits. No significant difference in QOL indices was found among the three groups at 1 wk before surgery. Compared with preoperative scores, the QOL of all patients had declined significantly at 1 wk after surgery (Figures 1 and 2). Preoperative and 1-wk postoperative global QOL scores in the Ivor Lewis, combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic, and left transthoracic groups were 80.8 ± 9.3 vs 32.0 ± 16.1, 81.1 ± 9.0 vs 53.3 ± 11.5, and 83.6 ± 11.2 vs 46.4 ± 11.3, respectively (all P < 0.001; Figure 1A). Most functional index scores decreased, with physical, emotional, social, and role scores showing the greatest declines (Figure 1B-E). The majority of symptomatic index scores, such as pain and weakness, increased (Figure 1F and G). QOL declined most in the Ivor Lewis group, which showed significantly lower physical and emotional function and significantly higher pain index scores compared with the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy group (all P < 0.05; Figure 1B, E and G). The degree of QOL decline in the left transthoracic esophagectomy group fell between those of the other two groups (Figures 1 and 2).

After surgery, QOL improved gradually in all three groups. All QOL indices were partially restored at 12 wk after surgery. Most functional indices approached preoperative levels in the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy group, but QOL status was not restored to preoperative levels in the left transthoracic esophagectomy and Ivor Lewis groups; the Ivor Lewis group showed the worst QOL status. Global QOL scores were higher in the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic group than in the other two groups at 1, 12 and 24 wk postoperatively (all P < 0.05; Figure 1A). Global QOL scores were higher in the left transthoracic group than in the Ivor Lewis group at 1 and 12 wk postoperatively (both P < 0.05), but showed no significant difference at 24 wk after surgery (P = 0.053). At 24 wk postoperatively, the incidence rates of pain in the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy, Ivor Lewis, and left transthoracic esophagectomy groups were 33.3%, 66.7% and 50%, respectively. All symptoms of dysphagia were alleviated in all groups (Figure 2).

Postoperative reflux occurred frequently after esophagectomy, and reflux scores showed no significant difference among groups during the 24-wk follow-up period. At 24 wk postoperatively, 66.7% of patients in the combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy group complained of varying degrees of reflux, and rates were similar in the other two groups (Figure 2B).

The World Health Organization defined QOL as “an individual’s perceptions of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, exceptions, standards and concerns”[19]. In the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer, more attention is usually given to the operation and postoperative survival rate than to QOL, even during long-term follow-up. However, patients often have many complaints about uncomfortable symptoms during this period; symptoms affecting postoperative QOL thus require further investigation and appropriate treatment. Today, within the context of the bio-psychosocial medical model, postoperative QOL should be included in the evaluation of treatment effectiveness. Unfortunately, not enough has been done in this respect. Thus, for patients with malignant neoplasms such as esophageal cancer, the improvement of QOL is especially important in the absence of a breakthrough in long-term survival rate improvement.

The surgical treatment of esophageal cancer has been a focus of modern medicine for more than 100 years. Given the deep location of the esophagus and the proximity of the intrathoracic esophagus to the heart, lungs, and other vital organs, esophagus substitutes are needed to restore the alimentary tract after the excision of the primary focus, and some doctors have advocated the “three-field esophagectomy” approach[20], such procedures are complex, difficult, and lengthy. Conventional open esophagectomy through the left thorax, a left thoracoabdominal incision or Ivor Lewis esophagectomy through the right thorax require the excision of the ribs and the use of a rib spreader, tearing part of the latissimus dorsi muscle or even severing the serratus anterior muscle. Thus, such surgery can result in major lesions that may not recover well after surgery and affect postoperative QOL. In this study, patients undergoing left transthoracic or Ivor Lewis esophagectomy showed significant postoperative declines in QOL, and several index scores (i.e., physical, social, and emotional function indices; pain scores) had not recovered well at 24 wk postoperatively. However, patients undergoing left transthoracic esophagectomy showed better postoperative QOL than patients in the Ivor Lewis group, especially with respect to physical function index scores. This result was likely because left transthoracic esophagectomy produces fewer lesions than the Ivor Lewis procedure, the patient’s position does not need to be changed during the operation, operation times are shorter, and the clearance is of smaller scope; left transthoracic esophagectomy thus inflicts less bodily harm, which benefits the restoration of postoperative QOL.

In the past 10 years, the updating of the theory of cancer therapy and improvements in technology and equipment, especially the introduction of new endoscopic imaging systems, have provided advantages for esophagectomy and lymphadenectomy such as the ability to perform these procedures under endoscopic guidance. With the accumulation of abundant experience in minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer, surgeons’ skills, and thereby the clinical effects of these procedures, have improved[21-25]. Wang et al[26] compared short-term QOL in patients with esophageal cancer after subtotal esophagectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open surgery. They mobilized the stomach with dissection of the celiac lymph node by laparoscopy or laparotomy. However, QOL has not been compared previously in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic, Ivor Lewis, or left thorax esophagectomy.

Since 2010, when our hospital began to perform combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy, we have performed this procedure in 50 patients with satisfying results. In this study, we found a smaller decline in postoperative QOL and a more rapid recovery in patients undergoing this procedure than in patients undergoing open esophagectomy, as indicated by symptomatic index and postoperative pain and weakness scores. Chronic pain complaints after thoracic surgery are clinically termed post-thoracotomy pain syndrome (PTPS). As an important QOL index, PTPS is a very common symptom that severely affects patients’ satisfaction with life. PTPS represents a significant clinical problem in 25%-60% of patients, and intercostal nerve injury seems to be the most important pathogenic factor[27]. Because of the smaller thoracic wall cut, patients in our cohort experienced less pain after combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy compared with open surgery. Because combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy does not require the severing of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles, most physical function index scores were restored to preoperative levels at 24 wk after surgery. The recovery of role, emotional, and social functions were also better in these patients than in the other two groups. Many patients scored lower in social and role functions due to postoperative surgical scars; thus, the smaller scars that remain after combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy may help to restore patients’ self-confidence, explaining why patients in this group scored higher than other groups on these two function indices.

A high incidence of postoperative reflux was observed in all of our patients during the 24-wk follow-up period; this might attributed to the elimination of the gastroesophageal sphincter mechanism preventing reflux, the persistence of gastric acid secretion, and the deterioration of esophageal clearance mechanisms[28,29]. In addition, gastric content may readily flow backward into the esophagus in the thoracic cavity due to negative pressure[30]. Although several anastomotic techniques have been used to construct a new antireflux barrier after esophagogastric junction resection[31-34], postoperative reflux after esophagectomy is a problem that warrants further attention and study.

Endoscopic esophagectomy has incomparable advantages given its minimally invasive nature in comparison with conventional surgery, but it also has some shortcomings. The procedure is less intuitive than an open operation, and thus has higher technical requirements for the operator. In cases of a huge tumor, obvious leftward displacement of the thoracic esophagus, or extensive pleural adhesion, endoscopic esophagectomy is very difficult to perform. As reported above, three cases in our series had to be converted to open operations for these reasons. However, with the continuous development of endoscopic equipment and improvement of surgical techniques, higher success rates of endoscopic esophagectomy are expected.

The currently leading viewpoint guiding the treatment of esophageal cancer is that the prognosis of this systemic disease depends mainly on biological activities and pathologic stage, whereas surgical treatment provides only local therapy. Thus, current surgical techniques of all types, including access through the left or right thorax and the use of one to three incisions, have little impact on patients’ long-term survival[35,36]. Thus, if indications are precisely defined, appropriate cases are selected, and endoscopically guided operation skills are perfect, minimally invasive surgery should achieve long-term survival rates similar to those of open surgery[37,38]. Lazzarino et al[39] compared patients’ survival status after minimally invasive or open esophagectomies performed in England between 1996 and 2007, and found better 1-year survival rates in patients undergoing minimally invasive procedures. On the basis of those findings, we performed minimally invasive surgery whenever possible for patients with esophageal cancer to improve their postoperative QOL. If camera-guided surgery is not available, an appropriate open surgical technique should be chosen according to the disease focus. For patients with distal esophageal cancer lacking evident mediastinal lymph node metastasis, we found that single-incision left transthoracic esophagectomy was much easier and produced fewer lesions. When the focal location is high or subcarinal lymph nodes or bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerves need to be cleared, the more thorough Ivor Lewis technique should be chosen.

This study had some limitations. The assignment of patients to the three groups was not strictly randomized, but was based on patients’ order of presentation. Furthermore, endoscopic esophagectomy was a new operation carried out in our hospital during the study period, and surgical proficiency increased gradually. These factors may have introduced biases in the analysis. The 24-wk follow-up period was also relatively short and the sample size was small, preventing the comparison of long-term curative effects for these different esophageal cancer treatments. To evaluate long-term effects and survival rates, larger samples and further observation are needed.

Conventional radical operations for esophageal cancer incur a large amount of trauma and result in poor postoperative quality of life (QOL). The improvement of postoperative QOL in patients with esophageal cancer is particularly important in the absence of a breakthrough in long-term survival rate improvement.

Recently developed minimally invasive surgical treatments for esophageal cancer, such as laparoscopic surgery, may improve postoperative QOL in patients with esophageal cancer.

In the past 10 years, the updating of the theory of cancer therapy and improvements in technology and equipment, especially the introduction of new endoscopic imaging systems, have provided advantages for esophagectomy and lymphadenectomy such as the ability to perform these procedures under endoscopic guidance. The authors compared postoperative QOL in patients after endoscopically guided esophagectomy or one of two other conventional open surgeries.

Compared with Ivor Lewis and left transthoracic esophagectomies, the study results suggested that combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy resulted in higher postoperative QOL, making it a preferable surgical approach for esophageal cancer.

QOL was defined by the World Health Organization as “an individual’s perceptions of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, exceptions, standards and concerns.”

This is a good clinical study in which the authors compare patients’ QOL following endoscopic esophagectomy or one of two other conventional open surgeries. The results are instructional and suggest that, in terms of postoperative QOL, combined thoracoscopic/laparoscopic esophagectomy is a preferable surgical approach for esophageal cancer.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Piers Anthony Cheyne Gatenby, Surgery and Interventional Science, London NW3 2PF, United Kingdom; James David Luketich, MD, Division of Thoracic and Foregut Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, PUH, C-800, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2115] [Cited by in RCA: 2219] [Article Influence: 100.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu PC, Posner MC. The role of surgery in the management of oesophageal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dubecz A, Sepesi B, Salvador R, Polomsky M, Watson TJ, Raymond DP, Jones CE, Litle VR, Wisnivesky JP, Peters JH. Surgical resection for locoregional esophageal cancer is underutilized in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:754-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jamieson GG, Mathew G, Ludemann R, Wayman J, Myers JC, Devitt PG. Postoperative mortality following oesophagectomy and problems in reporting its rate. Br J Surg. 2004;91:943-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Blazeby JM, Sanford E, Falk SJ, Alderson D, Donovan JL. Health-related quality of life during neoadjuvant treatment and surgery for localized esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1791-1799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reynolds JV, McLaughlin R, Moore J, Rowley S, Ravi N, Byrne PJ. Prospective evaluation of quality of life in patients with localized oesophageal cancer treated by multimodality therapy or surgery alone. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1084-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Viklund P, Lindblad M, Lu M, Ye W, Johansson J, Lagergren J. Risk factors for complications after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective population-based study in Sweden. Ann Surg. 2006;243:204-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H, Shima I, Toh Y, Tomita Y, Fujii T, Yamasaki K, Higaki K, Noake T. Mortality and morbidity rates, postoperative course, quality of life, and prognosis after extended radical lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Comparison of three-field lymphadenectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:654-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11469] [Article Influence: 358.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Hammerlid E, Fayers P, Sezer O, Koller M, Arraras J, Bottomley A, Vickery CW, Etienne PL. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1384-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jianping W, Zhonggeng C, Wenjuan L, Junnan C. Assessment of quality of life in cancer patients: eortc qlq-c30 for use in china. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2000;32:438-442. |

| 12. | Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Test/retest study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1249-1254. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fayers PM, Asronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: EORTC 2001; . |

| 14. | Xu WX, Qian Y, Chen ZD. Development and evaluation of measurement instrument of quality of life for patients with esophageal cancer Chinese version of EORTC QLQ-OES18. Modern Oncology. 2007;15:1792-1794. |

| 15. | Lagergren P, Avery KN, Hughes R, Barham CP, Alderson D, Falk SJ, Blazeby JM. Health-related quality of life among patients cured by surgery for esophageal cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:686-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Parameswaran R, Blazeby JM, Hughes R, Mitchell K, Berrisford RG, Wajed SA. Health-related quality of life after minimally invasive oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fagevik Olsén M, Larsson M, Hammerlid E, Lundell L. Physical function and quality of life after thoracoabdominal oesophageal resection. Results of a follow-up study. Dig Surg. 2005;22:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Blazeby JM, Williams MH, Brookes ST, Alderson D, Farndon JR. Quality of life measurement in patients with oesophageal cancer. Gut. 1995;37:505-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Orley J, Kuyken W. Quality of life assessment: International perspectives. Berlin: Springer-Verlag 1994; 1-200. |

| 20. | Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Kajiyama Y. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1994;220:364-372; discussion 372-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shiozaki H, Imamoto H, Shigeoka H, Imano M, Yano M. [Minimally invasive esophagectomy with 10 cm thoracotomy assisted thoracoscopy for the thoracic esophageal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2003;30:923-928. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas JM. Comparison of the outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;245:232-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Taguchi S, Osugi H, Higashino M, Tokuhara T, Takada N, Takemura M, Lee S, Kinoshita H. Comparison of three-field esophagectomy for esophageal cancer incorporating open or thoracoscopic thoracotomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1445-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Okushiba S, Ohno K, Itoh K, Ohkashiwa H, Omi M, Satou K, Kawarada Y, Morikawa T, Kondo S, Katoh H. Hand-assisted endoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2003;33:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Higashino M, Takemura M. [Indication and limitation of endoscopic surgical procedure for esophageal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2004;31:1481-1484. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Wang H, Feng M, Tan L, Wang Q. Comparison of the short-term quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer after subtotal esophagectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic or open surgery. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:408-414. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Wildgaard K, Ravn J, Kehlet H. Chronic post-thoracotomy pain: a critical review of pathogenic mechanisms and strategies for prevention. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:170-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yamamoto S, Makuuchi H, Shimada H, Chino O, Nishi T, Kise Y, Kenmochi T, Hara T. Clinical analysis of reflux esophagitis following esophagectomy with gastric tube reconstruction. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:342-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kaseno S. Clinical study of the reflux esophagitis following esophageal reconstruction using the gastric roll through the posterior mediastinum after radical esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 1999;60:306-315. |

| 30. | Aiko S, Yoshizumi Y, Ogawa H, Ishizuka T, Horio T, Kanai N, Nakayama T, Maehara T. Surgical attempts to avoid anastomotic leaks and reduce reflux esophagitis following esophagectomy for cancer. Japan Esophageal Society and Springer. 2008;5:141-148. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Lortat-Jacob JL, Maillard JN, Fekete F. A procedure to prevent reflux after esophagogastric resection: experience with 17 patients. Surgery. 1961;50:600-611. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Pearson FG, Henderson RD, Parrish RM. An operative technique for the control of reflux following esophagogastrostomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969;58:668-677 passim. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Demos NJ, Biele RM. Intercostal pedicle method for control of postresection esophagitis. Thirteen-year clinical study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;80:679-685. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Yalav E, Ercan S. Reservoir and globe-type antireflux surgical techniques in intrathoracic esophagogastrostomies. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:282-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hokamura N, Konishi T. [Current trends in surgical treatment of esophageal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2000;27:967-973. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Rindani R, Martin CJ, Cox MR. Transhiatal versus Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy: is there a difference? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Palanivelu C, Prakash A, Senthilkumar R, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajan PS, Venkatachlam S. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenectomy in prone position--experience of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nguyen NT, Hinojosa MW, Smith BR, Chang KJ, Gray J, Hoyt D. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: lessons learned from 104 operations. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1081-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lazzarino AI, Nagpal K, Bottle A, Faiz O, Moorthy K, Aylin P. Open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy: trends of utilization and associated outcomes in England. Ann Surg. 2010;252:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |