Published online Aug 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4237

Revised: April 25, 2012

Accepted: May 26, 2012

Published online: August 21, 2012

Spontaneous hemoperitoneum (SP) is defined as the presence of blood within the peritoneal cavity that is unrelated to trauma. Although there is a vast array of etiologies for SP, primary hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic adenoma are considered to be the most common causes. Hepatic metastatic tumor associated with spontaneous rupture is rare. SP from hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor may initially present with a sudden onset of abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis of SP, indicating its origin and etiology, and determining subsequent management. Herein, we report an uncommon case of hemoperitoneum from spontaneous rupture of a hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor in a young female patient. Interestingly, the contrast-enhanced CT findings demonstrated hypervascular hepatic masses with persistent enhancement at all phases, which were completely different from the common appearances of hepatic metastases. For SP resulting from hepatic metastatic tumors, surgical intervention is still the predominant therapeutic method, but the prognosis is very poor.

- Citation: Liu YH, Ma HX, Ji B, Cao DB. Spontaneous hemoperitoneum from hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(31): 4237-4240

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i31/4237.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4237

Spontaneous hemoperitoneum (SP) is defined as the presence of blood within the peritoneal cavity that is unrelated to trauma. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatic adenoma are considered to be the most common causes; however, hepatic metastatic tumors associated with SP are rare. Those metastatic tumors may include colon, lung, renal cell and testicular neoplasms, and Wilm’s tumor, but few cases of metastatic trophoblastic tumor responsible for HP have been reported, especially in the absent evidence of primary malignant tumor. Computed tomography (CT) plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis of SP. Metastatic liver tumors display variant appearances in routine CT scan and are often classified as hypervascular, hypovascular and nonvascular metastases on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan. Most of the hepatic metastatic tumors present with hypovascular appearances, namely mild enhancement in both the portal phase and delayed phase. But in our patient with hepatic trophoblastic tumor, there were typically unusual presentations, which showed almost identical enhancement patterns with abdominal aorta in all phases. To our knowledge, there are few reports of similar cases focusing on uncommon CT manifestations in hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor. We report an uncommon case of hemoperitoneum from spontaneous rupture of a hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor in a young female patient below.

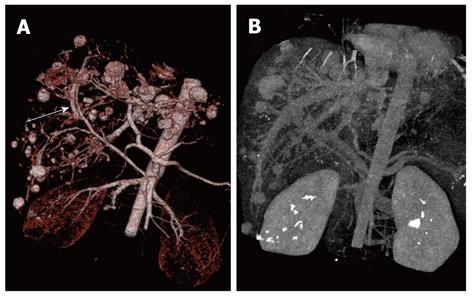

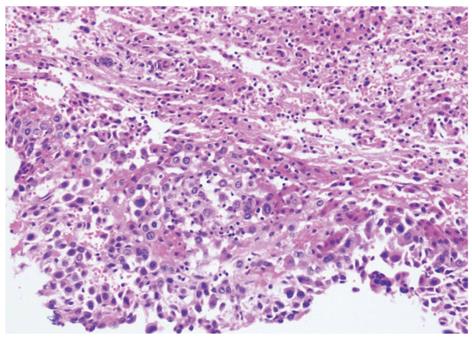

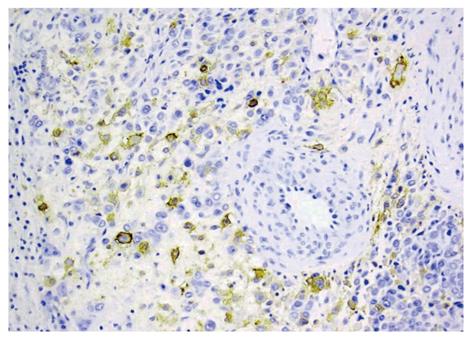

A 24-year-old girl was admitted to our emergency department because of sudden onset of abdominal pain, and emergent non-enhanced CT scan showed intrahepatic multiple lesions associated with rupture and bleeding into the peritoneal cavity (Figure 1). Three months ago, she underwent splenic repair, and her family could not tell about the specific cause even after she was discharged from the hospital. She had a history of pregnancy and abortion two years ago. Physical examination on admission was unremarkable except for mild epigastric tenderness and longitudinal abdominal scar. At exploratory laparotomy, there was dark red blood in the abdominal cavity. After cleaning of the blood, multiple cystic masses bulging from the surface of the liver were found, one of which was ruptured and then removed for pathological analysis. Her serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) levels were 94 mIU/mL (reference range: 0-6 mIU/mL), 1.01 ng/mL (reference range: < 7.0 ng/mL) and 46.86 ng/mL (reference range: < 3.4 ng/mL), respectively. Post-operative contrast-enhanced CT of abdomen showed multiple hepatic hypervascular masses keeping the similar enhancement with abdominal aorta in all phases (the diameter of the masses ranged from 0.8 cm to 2.8 cm) and arterioportal shunts (Figures 2, 3A and B). CT scan of the chest and pelvis revealed no abnormalities. Histopathological examination confirmed the tumor to be predominantly composed of mononuclear epithelioid cells with pink cytoplasm and large, irregularly shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoid (Figure 4). Immunostaining was positive for placental alkaline phosphatase (Figure 5), while negative for HepPar-1, smooth muscle actin. Hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor was diagnosed by histopathological examination and immunohistochemical analyses. No abnormality was found in the all-round gynecological checkup, especially in the uterus. The patient refused to chemotherapy and died a month later despite of receiving supportive treatment. Her family refused the autopsy.

SP, an uncommon cause of acute abdominal pain, is defined as the presence of blood within the peritoneal cavity that is unrelated to trauma. Its occurrence may be catastrophic. There are various causes for SP, such as hepatic, splenic, gynecological and vascular involvement, and altered coagulation status[1,2]. Therefore, underlying causes must be identified if the patient survives the initial events. As for hepatic causes, previously undetected liver lesion may be a relatively common cause of spontaneous rupture leading to hemoperitoneum, and unnoticeable minor trauma may be the precipitating factor. Hepatic adenoma and HCC developed from cirrhosis are the most common causes for SP[3,4], however, hepatic metastatic tumor associated with SP is rare, as most of them tend to be less invasive, and have less blood vessels and less propensities to penetrate the liver capsule as compared with HCC. In our case, hepatic metastatic tumor associated with SP was due to the rupture of hepatic metastasis of a trophoblastic tumor with hypervascularity, which was seldom found responsible for SP in clinical practice.

The mechanism for the rupture of hepatic metastasis remains unclear, but the large lesion adjacent to the liver capsule is at the greatest risk due to direct pressure against the capsular surface, especially in increased intra-abdominal pressure. Acute hemoperitoneum as a result of hemorrhage from liver metastasis is an uncommon but a terminal event. In a large report of 70 patients with SP, metastatic disease was only found responsible for one case[5]. Those metastatic lesions may include colon, lung, renal cell, testicular tumors, and Wilm’s tumor[6-8]. So, a thorough search should be made for evidence of a primary tumor that may have metastasized to the liver. However, hepatic involvement from trophoblastic tumor accounts for only 10% of the patients and occurs in the late course of the disease. Regression of a primary tumor after it has metastasized is not uncommon, and one-third of cases manifests as complications of metastatic diseases[9].

The available imaging modalities used for the diagnosis of SP include sonography, CT and magnetic resonance imaging. Meticulous imaging technique and careful observation of key imaging features are important for accurate characterization of the organ origin of the spontaneous bleeding. Currently, CT scan is the most frequently used modality in evaluating the patients with suspected hemoperitoneum[2,10,11]. Emphasis should be laid on detecting hemoperitoneum, then localizing the source of bleeding and finally detecting the primary cause. On CT imaging, the appearance of blood within the peritoneum varies depending on the site and the extent of bleeding, and the age of blood. If the time interval between bleeding and imaging is several hours, high attenuation clot may be seen. Over the next few days, the attenuation of the blood decreases, which becomes similar to simple fluid after 2-3 wk. High attenuation clots may appear at the site of the bleeding and suggest a clue as to the site of the bleeding origin. Once the presence of hemoperitoneum has been identified or active bleeding is controlled, a comprehensive search should be made further for an underlying cause. This may start with a careful evaluation of the liver and spleen, because they are the most common organs responsible for spontaneous bleeding. If the SP is derived from a hepatic or splenic cause, the peritoneal blood may be centered around the responsible lesion[12,13], as described in our case. Although hepatic metastases can come from many locations of the body, SP secondary to metastases exhibit similar findings on non-enhanced CT scan.

Dramatic advance in multi-detector technology has significantly improved the accuracy of CT and dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan which can identify imaging characteristics of intrahepatic lesions, especially the rare appearances from uncommon disease entity. Metastatic tumors of liver present with intra-liver occupied lesions on unenhanced CT scan, including multi-nodules similar to the “bull’s eye” sign, homogenized low-density mono-nodule, equal- or high-density mass and cystic lesion. Appearances of dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan for these disease entities may have variant enhancement patterns according to the vascularity of the primary tumor and are often classified as hypervascular, hypovascular and nonvascular metastases. Most of hepatic metastatic tumors show mild enhancement in the portal phase and delayed phase consistent with hypovascular lesions, while there were typically unusual presentations in our patient, which showed the synchronized enhancement with abdominal aorta in all phases. The similar case is extremely rare in the reported literature. Therefore, for a female patient in child-bearing age who presents with SP and unusual contrast-enhanced CT findings similar to our patient’s, we should be alert to the possibility of the spontaneous rupture of metastatic trophoblastic disease in the liver, even though the primary lesion is not found on that occasion.

Prognosis of patients with rupture hepatic metastasis of trophoblastic disease is extremely poor, and the choice of treatment depends on the tumor size, tumor location, severity of bleeding and the general condition of the patient. Surgery and embolisation with or without chemotherapy are the mandatory therapeutic choices[14,15]. Because of the severe condition of our patient, transcatheter arterial chemotherapeutic embolization is abortive.

In conclusion, we described the CT findings of SP secondary to rupture of hepatic metastatic trophoblastic disease in a female patient. Unusual enhancement patterns on contrast-enhanced CT scan will further enhance our recognition of the SP from hepatic metastatic trophoblastic disease and help differentiate it from other hypervascular hepatic masses.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Guideng Li, Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4120, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Lucey BC, Varghese JC, Anderson SW, Soto JA. Spontaneous hemoperitoneum: a bloody mess. Emerg Radiol. 2007;14:65-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lucey BC, Varghese JC, Soto JA. Spontaneous hemoperitoneum: causes and significance. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2005;34:182-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | da Fonseca CR, Duarte FP. [Hemoperitoneum as the form of presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. The contribution of computed tomography to the diagnosis]. Acta Med Port. 1999;12:223-226. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, van Delden OM, Ten Kate FJ, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Management of spontaneous haemorrhage and rupture of hepatocellular adenomas. A single centre experience. Liver Int. 2006;26:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen ZY, Qi QH, Dong ZL. Etiology and management of hemmorrhage in spontaneous liver rupture: a report of 70 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1063-1066. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gulati A, Vyas S, Lal A, Harsha T S, Gupta V, Nijhawan R, Khandelwal N. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from choriocarcinoma: a review of imaging and management. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:384-387. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kadowaki T, Hamada H, Yokoyama A, Ito R, Ishimaru S, Ohnishi H, Katayama H, Oshima M, Okura T, Kito K. Hemoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 2005;44:290-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tung CF, Chang CS, Chow WK, Peng YC, Hwang JI, Wen MC. Hemoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous rupture of metastatic epidermoid carcinoma of liver: case report and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1415-1417. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Heaton GE, Matthews TH, Christopherson WM. Malignant trophoblastic tumors with massive hemorrhage presenting as liver primary. A report of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:342-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mortele KJ, Cantisani V, Brown DL, Ros PR. Spontaneous intraperitoneal hemorrhage: imaging features. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:1183-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lubner M, Menias C, Rucker C, Bhalla S, Peterson CM, Wang L, Gratz B. Blood in the belly: CT findings of hemoperitoneum. Radiographics. 2007;27:109-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pombo F, Arrojo L, Perez-Fontan J. Haemoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: CT diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:321-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Becker CD, Mentha G, Terrier F. Blunt abdominal trauma in adults: role of CT in the diagnosis and management of visceral injuries. Part 1: liver and spleen. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tarantino L, Sordelli I, Calise F, Ripa C, Perrotta M, Sperlongano P. Prognosis of patients with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Updates Surg. 2011;63:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lazaridis G, Pentheroudakis G, Fountzilas G, Pavlidis N. Liver metastases from cancer of unknown primary (CUPL): a retrospective analysis of presentation, management and prognosis in 49 patients and systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |