INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related maneuvers are difficult in patients with altered gastrointestinal (GI) anatomy due to previous abdominal surgery. ERCP success rates using conventional methods in patients after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy and Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy are reported to be as low as 52%[1,2], 51%[3], and 33%[2], respectively. If the papilla or biliary anastomosis in the afferent loop cannot be reached by an ordinary duodenoscope because of excessive intestinal length and/or sharp angulation of the anastomosis, it has recently become possible to use a double-balloon enteroscope (DBE) for ERCP. There are several hurdles for this technique, including reaching the papilla or biliary anastomosis, selective duct cannulation, and accomplishment of the treatment. The enteroscope is advanced through the overtube into the afferent jejunal loop using the push-and-pull double balloon technique. Identifying the opening of the afferent loop and coping with sharp angulation of the anastomosis are the keys for the successful endoscope insertion. Once the papilla or biliary anastomosis is reached, however, endoscopic interventions via DBE in these postoperative settings remain the most difficult ERCP manipulations because of the lack of an elevator and the use of extra-long ERCP accessories.

Here, we report three cases with choledocholithiasis treated with DBE-assisted ERCP and demonstrate the usefulness of direct cholangioscopy with an ultra-slim gastroscope for subsequent treatment.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

An 80-year-old man was referred for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. He had undergone partial gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy for gastric carcinoma five years before. With the DBE (EC-450BI5; Fujinon, Osaka, Japan) with a 152 cm working length and a 2.8 mm instrumental channel, the papilla could be reached via the Roux-en-Y anastomosis under carbon dioxide insufflation. Cannulation of the papilla and cholangiography revealed a dilated bile duct and multiple stones (maximum size 20 mm) piled up at the lower to middle part of the bile duct (Figure 1A). Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was performed with a conventional sphincterotome, placing the papilla of Vater at the 6 o’clock position. After mechanical lithotripsy with a 7-Fr crusher catheter (Xemex crusher catheter; Zeon Medical, Tokyo, Japan), stone extraction was attempted with a basket catheter but frequently failed because the catheter was inserted into the dilated cystic duct. Because the same attempt was performed unsuccessfully during another session, the enteroscope was exchanged for an ultra-slim gastroscope (EG-530NW; Fujinon, outer diameter 5.9 mm), leaving the overtube with its balloon inflated. The ultra-slim endoscope was introduced through an incision in the overtube, which was made at a point 100 cm from its tip. The ultra-slim endoscope was advanced through the overtube up to the papilla and was directly inserted into the bile duct after papillary dilation using a large balloon catheter (CRE balloon dilator; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1B and C). Cholangioscopy showed multiple stones inside the dilated bile duct and the cystic duct. The stones were all removed with a 5-Fr basket catheter (Basket catheter, diamond type; MTW Endoskopie, Wesel, Germany) under direct visual control (Figure 2). The patient had a good clinical course after the procedure, and no adverse events occurred.

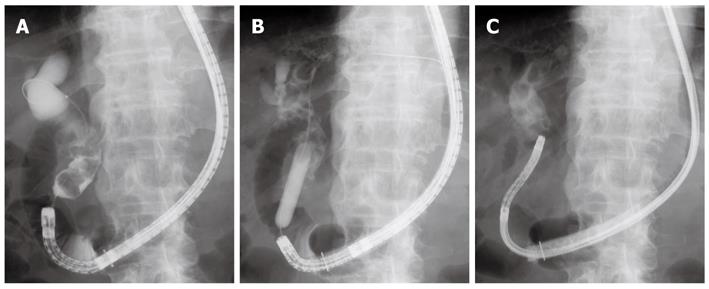

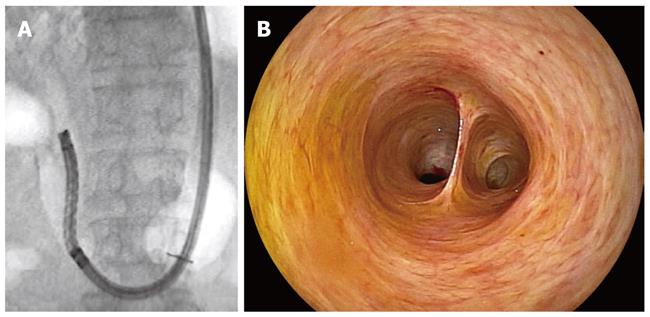

Figure 1 X-ray images.

A: Cholangiography revealed a dilated bile duct and multiple stones piled up at the lower to middle part of the bile duct; B: Papillary dilation using a large balloon catheter; C: An ultra-slim gastroscope was introduced directly into the bile duct.

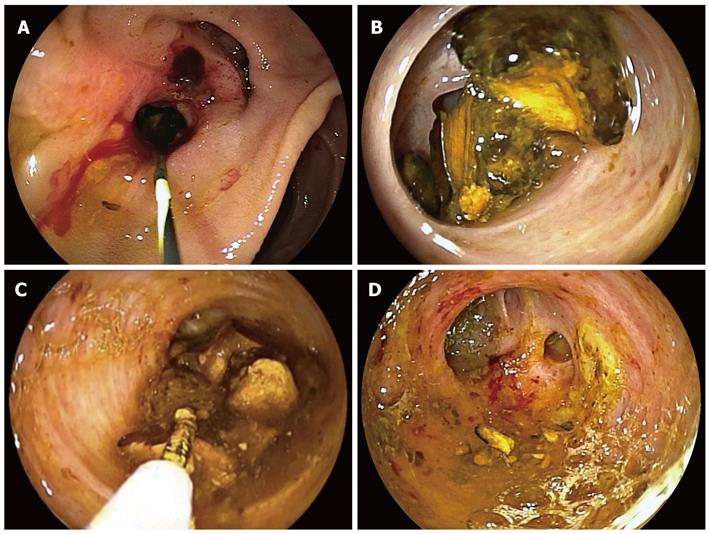

Figure 2 Endoscopic images.

A: The papilla of Vater after balloon dilation; B: Cholangioscopy showed multiple stones inside the bile duct; C, D: The stones were all removed with a 5-Fr basket catheter under direct visual control.

Case 2

An 89-year-old man developed acute cholangitis with choledocholithiasis. He had undergone partial gastrectomy with Billroth II gastrojejunostomy for gastric carcinoma 21 years before. Because of the long afferent loop, the DBE (EC-450BI5; Fujinon, Osaka, Japan) was used to gain access to the papilla under carbon dioxide insufflation. Cannulation of the papilla and cholangiography showed two bile duct stones (maximum size 15 mm) at the middle part of the bile duct. After EST with a conventional sphincterotome, a smaller stone located distally was extracted with a basket catheter (Figure 3). Another stone could not be removed despite all possible efforts because of its impaction. The enteroscope was then exchanged for an ultra-slim gastroscope as described above. The endoscope was inserted directly into the bile duct, revealing an impacted stone inside the duct. The stone was removed successfully with a 5-Fr basket catheter under direct visual control, and the proximal bile duct was also investigated (Figure 4A-C). The patient had a good clinical course after the procedure, and no adverse events occurred.

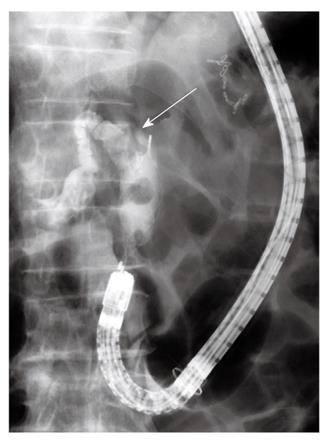

Figure 3 Cholangiography.

A smaller stone located distally was extracted with a basket catheter. Another stone was impacted inside the bile duct (arrow).

Figure 4 Direct cholangioscopy with an ultra-slim gastroscope.

A: Cholangioscopy revealed an impacted stone inside the bile duct; B: The stone was removed with a 5-Fr basket catheter under direct visual control; C: The proximal bile duct was also investigated.

Case 3

A 73-year-old man was referred because of cholestasis and suspected choledocholithiasis. He had undergone partial gastrectomy with Billroth II gastrojejunostomy for gastric ulcer 43 years before. The DBE (EC-450BI5; Fujinon, Osaka, Japan) was first inserted into the efferent loop and was then introduced up to the papilla via Braun’s anastomosis under carbon dioxide insufflation. Cannulation of the papilla and cholangiography revealed several small stones (5 mm in size) inside the bile duct. After EST with a conventional sphincterotome, the stones were extracted with a basket catheter and a retrieval balloon (Figure 5A-C). An ultra-slim gastroscope was then introduced into the bile duct as described above. Cholangioscopy confirmed complete clearance of the stones inside the bile duct (Figure 6A and B). The patient had a good clinical course after the procedure, and no adverse events occurred.

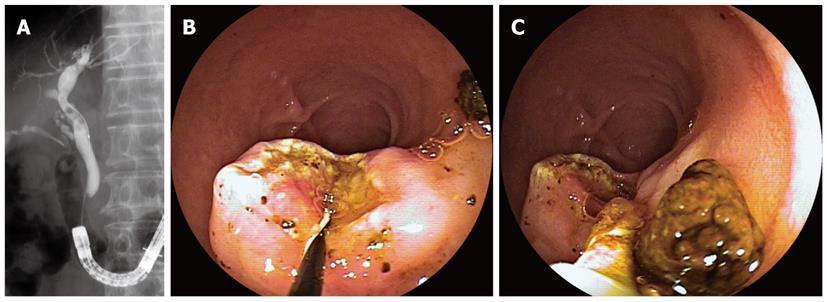

Figure 5 X-ray and endoscopic images.

A: Cholangiography revealed several small stones inside the bile duct; B: The papilla of Vater after endoscopic sphincterotomy; C: The bile duct stones were extracted with a basket catheter and a retrieval balloon.

Figure 6 Direct cholangioscopy.

A: An ultra-slim gastroscope was introduced directly into the bile duct after removal of bile duct stones; B: Cholangioscopy confirmed complete clearance of the duct.

DISCUSSION

Since the first report[4] of a successful DBE-assisted cholangiography in a pediatric case with late biliary stricture of choledochojejunostomy after living donor liver transplantation, many case series[5-17] have reported the effectiveness of DBE-assisted ERCP for pancreatobiliary disorders in various postoperative settings. In most previous reports[6-8,10-12,15,16], the therapeutic enteroscope, which has a 200-cm working length and a 2.8-mm instrumental channel, has been used for DBE-assisted ERCP. Recently, the single-balloon enteroscope (SBE) system (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), which consists of an enteroscope without the balloon at the tip of the endoscope and an overtube equipped with a balloon, has also been used for ERCP in patients with altered postsurgical anatomy with similar technical success rates[18-20].

The maneuverability of these enteroscopes is rather poor and only limited ERCP accessories are available for these endoscopes because of the long working length. To overcome these drawbacks, Fähndrich et al[9] reported a facilitated method for endoscopic interventions at the bile duct during DBE-assisted ERCP that involved exchanging the enteroscope with an ordinary gastroscope after incision of the overtube once the papilla or the biliary anastomosis was reached. This technique is favorably performed in our country when the SBE or the “long” DBE is used for ERCP because long-length ERCP accessories are not commercially available in Japan. Alternatively, the DBE, which has a 152 cm working length and a 2.8 mm instrumental channel, can be used. This instrument is the “short” DBE for which conventional ERCP accessories are available. With this enteroscope, Shimatani et al[13] performed DBE-assisted ERCP and related therapeutic maneuvers in 68 patients with altered GI anatomies with an extremely high success rate.

Another disadvantage of DBE-assisted ERCP is that the enteroscope is forward-viewing. The lack of an elevator and the absence of the side-viewing perspective reduce the success rate of cannulation or sphincterotomy. Moreover, additional treatment becomes difficult in cases such as the retained bile duct stones described here, even if access to the biliary duct is obtained. Direct visualization of the bile duct with an ultra-slim gastroscope expands the options for therapy inside the duct because the endoscope has a 2 mm instrumental channel for which 5-Fr accessories (including the biopsy forceps, the basket catheter, the laser lithotripsy probe, and the argon plasma coagulation probe) are available. The ultra-slim endoscope was introduced through incision of the overtube. The overtube was incised for three-quarters of its circumference on the side opposite of the pressure line, as described by Fähndrich et al[9] Care was taken not to damage the pressure line of the overtube to maintain the inflation of the balloon. Although this technique is only possible when the intact papilla or biliary anastomosis is reached with (at most) 100 cm of the enteroscope introduced, it is easy to advance the ultra-slim endoscope into the bile duct through the papilla treated with EST or balloon dilation because the approach is from the distal side of the afferent loop.

We did not encounter any adverse events in this case series. However, care must be taken because DBE-assisted ERCP can potentially cause serious complications, such as perforation, bleeding, or pancreatitis, during or after the scope insertion and ERCP procedures. Although no serious complications of direct cholangioscopy with an ultra-slim endoscope have been reported[21,22], there is still a risk of air embolism; pneumobilia is often recognized after EST. Carbon dioxide insufflation during the DBE procedure may be effective in preventing this complication.

In conclusion, DBE-assisted ERCP appears to be a promising method; however, this technique still has several disadvantages. Direct cholangioscopy with an ultra-slim gastroscope compensates for drawbacks of the enteroscope and facilitates subsequent treatment within the bile duct. This procedure may represent another option during DBE-assisted ERCP.