Published online Feb 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.1030

Revised: November 11, 2010

Accepted: November 18, 2010

Published online: February 28, 2011

AIM: To investigate the small bowel of seronegative spondyloarthropathy (SpA) patients in order to ascertain the presence of mucosal lesions.

METHODS: Between January 2008 and June 2010, 54 consecutive patients were enrolled and submitted to avideo capsule endoscopy (VCE) examination. History and demographic data were taken, as well as the history of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) consumption. After reading each VCE recording, a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change (Lewis score) was calculated. Statistical analysis of the data was performed.

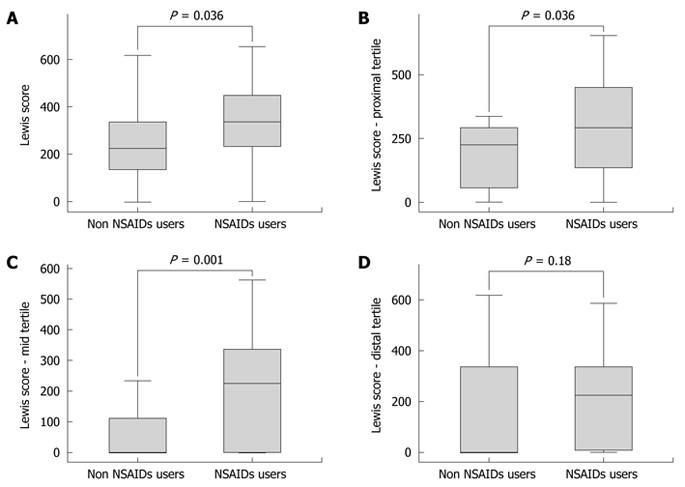

RESULTS: The Lewis score for the whole cohort was 397.73. It was higher in the NSAID consumption subgroup (P = 0.036). The difference in Lewis score between NSAID users and non-users was reproduced for the first and second proximal tertiles of the small bowel, but not for its distal third (P values of 0.036, 0.001 and 0.18, respectively). There was no statistical significant difference between the groups with regard to age or sex of the patients.

CONCLUSION: The intestinal inflammatory involvement of SpA patients is more prominent in NSAID users for the proximal/mid small bowel, but not for its distal part.

- Citation: Rimbaş M, Marinescu M, Voiosu MR, Băicuş CR, Caraiola S, Nicolau A, Niţescu D, Badea GC, Pârvu MI. NSAID-induced deleterious effects on the proximal and mid small bowel in seronegative spondyloarthropathy patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(8): 1030-1035

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i8/1030.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.1030

Spondyloarthropathies (SpAs) are a group of related disorders with common clinical and genetic characteristics and a global prevalence between 0.5% and 1%[1]. Entities included in the group of SpAs are ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, undifferentiated SpA, juvenile onset SpA and SpA in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Some researchers also include within this concept Behçet’s disease-associated SpA[2].

Over 20 years ago, Mielants et al[3] showed that a substantial number of these patients have subclinical ileal inflammation. They reported finding macroscopic ileal abnormalities in up to 30% of SpA patients, including erythema, edema, ulceration, granulation, and a cobblestone appearance of the ileal mucosa. Moreover, inflammatory lesions macroscopically resembling those found in SpAs are induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) consumption, and about two thirds of NSAID users demonstrate intestinal abnormalities[4]; this is important, since many of the SpA patients use NSAIDs in the treatment of their disease.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is a diagnostic tool that has recently made non-invasive imaging of the entire small bowel possible. This technique has been demonstrated as the first-line diagnostic tool for detecting small bowel pathologies[5], and we have considered it to be suited for the evaluation of small bowel mucosal lesions.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the pattern, frequency, and severity of small bowel mucosal injury in patients with SpAs as assessed by VCE, and to clarify the role of NSAIDs in the occurrence of the lesions, given the inflammatory involvement of the small bowel that already exists in the SpA control group[6].

This is a single-center observational study in a tertiary referral teaching hospital in Bucharest, Romania, conducted from January 2008 to June 2010. All consecutive adult patients evaluated by the study team with a form of seronegative SpA (as defined by an Amor score ≥ 6[1]) in whom no intestinal stenosis or obstruction was suspected were included, if they agreed to take part in the experiment. Exclusion criteria were also: pregnancy, swallowing disorders or the presence of cardiac pace-makers, and history of IBD. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and local regulations. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and all the patients agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent before enrolling.

The patients were investigated using VCE examination. The preparation for the procedure included a fasting period of 12 h and a routine PEG-based bowel preparation (Endofalk, Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) with 2 L administered in the evening before and 1 L on the morning of the procedure. Simethicone 80 mg was given orally 15 to 20 min prior to the initiation of VCE examination (Espumisan L, Berlin Chemie AG, Berlin, Germany). Video capsule examination was performed with PillCam SB2 capsules (Given Imaging, Yokneam, Israel). The RAPID™ versions that were used for reading the VCE recordings were 5.0, and, starting with December 2009 recordings, 6.0.

Patients were allowed to drink clear liquids 2 h after VCE ingestion and were free to engage in their normal daily activities. They were allowed to eat a light lunch 4 h after capsule ingestion and returned for removal of the recorder 8-9 h after ingestion. No adverse effects were reported and all the capsules were excreted.

Two endoscopists (MR and MM) with experience in VCE examination reviewed the findings of VCE. Capsule endoscopy results were interpreted, and the Lewis score was calculated for every patient by one endoscopist (MR) in each tertile of the small bowel (stenosis score included), and then for the whole bowel.

Data regarding patient demographics and treatment taken were also retrieved, with emphasis on concurrent NSAID consumption. Collected data were recorded on a preformed questionnaire and introduced afterwards in the SPSS database. Results are expressed as frequencies for categorical variables (further analyzed by Fisher’s exact test), mean and standard deviation for normal continuous variables (analyzed by Student’s t test), and median and extremes for non-normal continuous variables (analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test). Hypothesis testing was 2-tailed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

The statistical software package SPSS for Windows Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze the data.

Fifty-four patients (27 males and 27 females) were enrolled. The rheumatologic disease was ankylosing spondylitis in 36 patients (66%), psoriatic SpA in 3 (6%), undifferentiated SpA in 9 (17%) and 6 patients concurrently satisfied the criteria for Behçet’s disease and SpA (11%) (Table 1).

| Diagnosis | NSAID users | Non NSAID users |

| Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 36) | ||

| Males | 13 | 7 |

| Females | 9 | 7 |

| Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy (n = 3) | ||

| Males | 1 | 1 |

| Females | 1 | 0 |

| Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy (n = 9) | ||

| Males | 2 | 2 |

| Females | 2 | 3 |

| Behçet-associated spondyloarthropathy (n = 6) | ||

| Males | 1 | 0 |

| Females | 2 | 3 |

Thirty-one patients (57%) were concomitantly treated with at least one NSAID. The mean age was 38.65 ± 11.58 years for controls vs 37.87 ± 10.63 years for NSAID users (P = 0.79, T-Test, independent samples test). There were more males in the NSAID user (54.8%) vs non-NSAID user subgroup (43.5%) (P = 0.41, T-Test, paired samples correlations).

There was a large heterogeneity regarding the type of drug [either cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective or non-selective, or a combination of them], the doses taken (some patients were only taking acetylsalicylic acid in antiaggregant doses) and the duration of NSAID use (weeks to years).

The Lewis score for the whole small bowel could be calculated in 52 patients (96%). In one of these patients, although the score could not be calculated for the distal tertile, the extremely high value in the mid tertile was extrapolated for the whole bowel; regardless, due to the fact that this subject had a very high discordant value of the Lewis score (4846), he was not considered for the descriptive and statistical analysis of the data. Approximating the capsule final position in the remaining 2 patients, the Lewis score could be estimated only for the proximal third of the small bowel because of the late passage of the video capsule through the pyloric ring into the small bowel.

The intraobserver reproducibility[7] for the Lewis score was assessed in 20 patients, and was considered to be high-coefficient of variation reached 3.52%.

The mean value of the Lewis score for the whole cohort was 397.73 (range 0-1630, standard deviation 401.46), with mean values of 340.64, 138.92 and 215.63 for the proximal, mid and distal tertiles of the small bowel, respectively.

There was a significant difference in the Lewis scores for the whole small bowel between the subgroups with and without NSAID consumption (P = 0.036) (Table 2 and Figure 1A). The difference was reproduced for the proximal and mid small bowel tertiles, but not for the distal tertile (P values of 0.036, 0.001 and 0.18, respectively) (Table 2 and Figure 1B-D).

The term SpA indicates a group of related diseases, all sharing common clinical features which are HLA-B27 positivity, sacroiliitis, inflammatory low back pain and oligoarticular asymmetric synovitis. The need for a standardized approach led to the development of the classification criteria proposed by Amor et al[1] which consider clinical and historical symptoms, radiologic findings, genetic background and response to treatment. Given the high diagnostic sensitivity (85%) and specificity (95%), we used these criteria for our study; a patient was considered to have SpA if the sum of the criteria scores was at least 6.

SpAs are associated with several extra-articular manifestations including inflammatory gut lesions, the latter being reported in 25%-75% of patients, depending on the subtype of SpA[8]. Although some of these patients may evolve to overt IBD, the immunological link between SpA and IBD is still poorly understood[9], the genetic or environmental factors determining the progression within this cascade being largely unknown[10].

A number of studies using different methodologies have evaluated the potential deleterious effects of NSAIDs on the small bowel. Considered together, they suggest that mild NSAID-related intestinal injury is common[11]-up to two-thirds of NSAID users demonstrate intestinal inflammation on VCE examination[12-14].

Having the above background, our aim was to investigate, using VCE examination, the possibility that NSAIDs could determine supplementary small bowel injury in SpA patients, these subjects being already predisposed to having mild inflammatory involvement of the bowel[15].

The design of the study included calculation of the Lewis score, facilitated by latest versions of the RAPID™ software. The Lewis score represents a capsule endoscopy scoring index developed for quantification of small intestinal mucosal disease activity[16]. It evaluates the aspect of the mucosal villi and the presence of ulcerative lesions and stenoses of the bowel lumen. A score is calculated for each tertile of the small bowel (proximal, mid, distal-resulting from dividing into three the time the capsule spent in the small bowel), and the total score equals the highest of these values plus the stenosis score. The Lewis score can range from 0 to 7840, and values below 136 are considered within normal.

A problem of the present study is represented by the large heterogeneity in the type of NSAID drug, the doses taken and the duration of NSAID use, therefore we had to group the subjects only according to NSAID concurrent use. This meant that we included in the same group of NSAID consumption patients those who ingested COX-2 selective and non-selective drugs. This might have been not so very wrong, because recent studies demonstrate that COX-2 inhibitors may not be more protective than some non-selective NSAIDs[17]. The NSAID doses also varied widely in our study, as well as the amount of time over which the drugs were taken. Therefore, we could not evaluate the effects of different doses and durations of treatment on the small bowel. Another limitation of the present study is represented by the fact that many of the patients also received as part of their treatment immunosuppressive drugs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy, or a combination of these.

In the present study, mild inflammatory involvement of the small bowel has been found in the whole cohort of SpA patients, given that the mean value of the Lewis score was 397.73. Subjects with NSAID consumption had more significant inflammatory lesions when the evaluation was performed for the whole small bowel. This result was expected because of the NSAID potential to induce small bowel inflammatory lesions. The above difference was reproduced for the proximal and mid small bowel tertiles but, surprisingly, not for the distal tertile, where there was no difference in bowel involvement between the NSAID concomitant users and non-users.

As it has already been established that NSAID intake predisposes to lesions in the distal small bowel[11], partly because of the use of enteric-coated, sustained-release, or slow-release NSAIDs[18], and because of the potential of NSAIDs to exacerbate the intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease-an entity related to the concept of SpA and considered to be located mainly in the distal small bowel-we were expecting to find more lesions in the NSAID consumption group in the distal tertile of the small bowel.

Other studies have already been performed to detect small bowel mucosal abnormalities in patients with SpAs using endoscopy techniques. Significant small bowel findings (erythema, mucosal breaks, aphthous or linear ulcers, and erosions) were detected by capsule endoscopy in one third of patients in a small SpA recent series[19], but in this study patients who were on NSAIDs in the 2 mo prior to enrollment were strictly excluded and the Lewis score was not calculated.

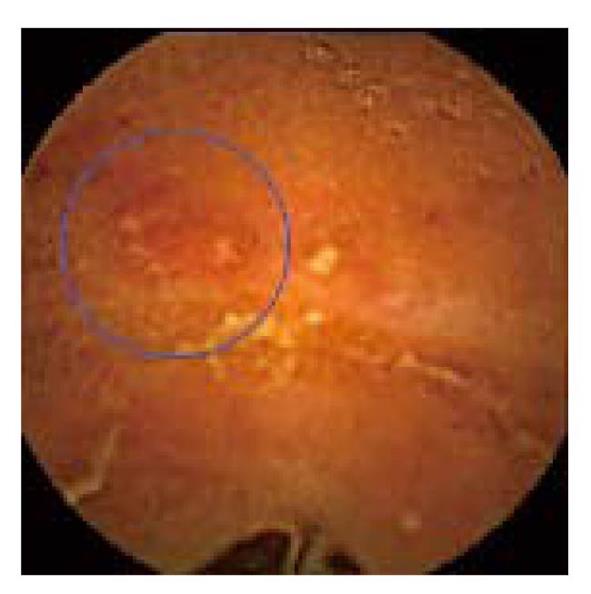

Up till now, the participation of the NSAIDs in the generation of bowel lesions in SpAs could only be postulated[20]. At the mucosal level, predicted mechanisms of NSAID injury are inhibition of protective prostaglandins, alterations in blood flow, and increased small intestinal permeability with subsequent invasion by luminal factors. The mucosal damage may lead to inflammation and ulceration[11], but there is nothing endoscopically specific about NSAID-induced gut lesions[12] (Figure 2); in the differential diagnosis could be included infectious etiologies, IBD, ischemia, radiation enteritis, vasculitides, and other drugs[11].

The present study is not intended to delineate which of the bowel lesions are due to NSAID intake and which to the rheumatologic disease. It only aims to identify the pattern of involvement of the small bowel when the two conditions superimpose. It is worth mentioning that the statistically significant differences between the NSAID users and non-users regarding bowel lesions found in our study were actually small (differences in the mean values of the Lewis scores of 93.92, 201.69 and 133.43 for the whole small bowel, and proximal and mid tertiles, respectively). It is not clear why the distal part of the small bowel is not influenced by NSAID consumption in this subset of patients.

In our view, there remains a great deal of uncertainty regarding the place of invasive methods, such as push- or double-balloon enteroscopy, in providing histological assessment of the abnormalities found on VCE. Another unresolved issue is represented by the persistence of these lesions, when stopping or continuing NSAID intake. Further studies are needed in the era of biological therapy to elucidate the clinical relevance of the lesions that we have detected and their possible influences on prognosis and further management of SpA patients.

The term spondyloarthropathy (SpA) indicates a group of related diseases, all sharing common clinical features such as the presence of HLA-B27 antigen and particular rheumatologic involvement (sacroiliitis, inflammatory low back pain and oligoarticular asymmetric synovitis). Entities included in the group of SpAs are ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, undifferentiated SpA, juvenile onset SpA and SpA in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. SpAs are associated with several extra-articular manifestations, including inflammatory gut lesions. However, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), frequently used to treat these patients, have the potential of inducing intestinal injury.

Having the above background, our aim was to investigate, using videocapsule examination, the possibility that NSAIDs could determine supplementary small bowel injury in the subgroup of patients with a form of SpA, these subjects being already predisposed to having mild inflammatory involvement of the bowel.

We found a mild inflammatory involvement of the small bowel in all SpA patients. Subjects with NSAID consumption had more significant inflammatory lesions in the whole small bowel. The above difference was reproduced for the proximal and mid small bowel tertiles but, surprisingly, not for the distal tertile, where there was no difference in bowel involvement between the NSAID concomitant users and non-users.

In our view, there remains a great deal of uncertainty regarding the place of invasive methods, such as push- or double-balloon enteroscopy, in providing histological confirmation of the abnormalities found on capsule endoscopy. Another unanswered question is how stable these lesions are, when stopping or continuing NSAID intake. Further studies will be needed in this era of biological therapy to elucidate the clinical relevance of the lesions that we detected and their possible influence on prognosis and further management of the SpA patients.

Based on the background that NSAID intake has potential deleterious effects on the small bowel, and SpAs are associated with inflammatory gut lesions, the authors designed this statistical study, trying to provide more evidence for the participation of NSAIDs in generation of bowel lesions in SpA patients. The results confirmed the inflammatory involvement of small bowel, especially in the proximal and mid tertiles, in SpA patients that have been treated with NSAIDs. The conclusion is of interest.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Fen Liu, University of Minnesota, 6-155 Jackson Hall, 321 Church Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0375, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Amor B, Dougados M, Mijiyawa M. [Criteria of the classification of spondylarthropathies]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1990;57:85-89. |

| 2. | Chang HK, Lee DH, Jung SM, Choi SJ, Kim JU, Choi YJ, Baek SK, Cheon KS, Cho EH, Won KS. The comparison between Behçet's disease and spondyloarthritides: does Behçet's disease belong to the spondyloarthropathy complex? J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:524-529. |

| 3. | Mielants H, Veys EM, Cuvelier C, de Vos M. Ileocolonoscopic findings in seronegative spondylarthropathies. Br J Rheumatol. 1988;27 Suppl 2:95-105. |

| 4. | Caunedo-Alvarez A, Gómez-Rodríguez BJ, Romero-Vázquez J, Argüelles-Arias F, Romero-Castro R, García-Montes JM, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Herrerías-Gutiérrez JM. Macroscopic small bowel mucosal injury caused by chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) use as assessed by capsule endoscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:80-85. |

| 5. | Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Spada C, Riccioni ME, Rey JF, Niv Y, Delvaux M, de Franchis R, Costamagna G. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE): recommendations (2009) on clinical use of video capsule endoscopy to investigate small-bowel, esophageal and colonic diseases. Endoscopy. 2010;42:220-227. |

| 6. | Rimbaş M, Marinescu M, Voiosu MR. Bowel lesions in ankylosing spondylitis. Is it the disease or the treatment? Maedica. 2009;4:253-256. |

| 7. | Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307-310. |

| 8. | Mielants H, De Keyser F, Baeten D, Van den Bosch F. Gut inflammation in the spondyloarthropathies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:188-194. |

| 9. | Fantini MC, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Common immunologic mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease and spondylarthropathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2472-2478. |

| 10. | De Keyser F, Mielants H. The gut in ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies: inflammation beneath the surface. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2306-2307. |

| 11. | Song LMWK, Marcon NE; NSAIDs: Adverse effects on the distal small bowel and colon. In: UpToDate online 18.2. (May 2010). . |

| 12. | Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA. Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55-59. |

| 13. | Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Theodors A, Gonzalez J, Bjarnason I. A quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1172-1178. |

| 14. | Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832-1847. |

| 15. | Rimbaş M, Marinescu M, Voiosu MR. Bowel lesions in spondyloarthritides. Rom J Intern Med. 2009;47:75-85. |

| 16. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. |

| 17. | Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Seigal A, Bjarnason II, Scott D, Birgisson S, Bjarnason I. Long-term effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 selective agents on the small bowel: a cross-sectional capsule enteroscopy study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1040-1045. |

| 18. | Reuter BK, Davies NM, Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in rats: role of permeability, bacteria, and enterohepatic circulation. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:109-117. |

| 19. | Eliakim R, Karban A, Markovits D, Bardan E, Bar-Meir S, Abramowich D, Scapa E. Comparison of capsule endoscopy with ileocolonoscopy for detecting small-bowel lesions in patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1165-1169. |

| 20. | Orlando A, Renna S, Perricone G, Cottone M. Gastrointestinal lesions associated with spondyloarthropathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2443-2448. |