Published online Aug 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3596

Revised: January 22, 2011

Accepted: January 29, 2011

Published online: August 21, 2011

AIM: To summarize clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features of special diaphragm-like strictures found in small bowel, with no patient use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

METHODS: From January 2000 to December 2009, 5 cases (2 men and 3 women, with a mean age of 41.6 years) were diagnosed as having diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel on imaging, operation and pathology. All the patients denied the use of NSAIDs. The clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic findings in these 5 patients were retrospectively reviewed from the hospital database. Images of capsule endoscopy (CE) and small bowel follow-through (SBFT) obtained in 3 and 3 patients, respectively, and images of double-balloon enteroscopy and computed tomography enterography (CTE) obtained in all 5 patients were available for review.

RESULTS: All patients presented with long-term (2-16 years) symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and varying degrees of anemia. There was only one stricture in four cases and three lesions in one case, and all the lesions were located in the middle or distal segment of ileum. Circumferential stricture was shown in the small bowel in three cases in the CE image, but the capsule was retained in the small bowel of 2 patients. Routine abdomen computed tomography scan showed no other abnormal results except gallstones in one patient. The lesions were shown as circumferential strictures accompanied by dilated small bowel loops in the small bowel on the images of CTE (in all 5 cases), SBFT (in 2 cases) and double-balloon enteroscopy (in all cases). On microscopy, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and circumferential diaphragm were found in all lesions.

CONCLUSION: Diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel might be a special consequence of unclear damaging insults to the intestine, having similar clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features.

- Citation: Wang ML, Miao F, Tang YH, Zhao XS, Zhong J, Yuan F. Special diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel unrelated to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(31): 3596-3604

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i31/3596.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3596

Many medications, diseases and processes may cause insult to the small bowel and result in strictures of the bowel cavity, such as potassium chloride tablets, surgical anastomoses, radiation, ischemia, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, eosinophilic enteritis, lymphoma, etc.

Diaphragm disease was first defined by Lang et al[1] in 1988, who described the pathologic findings of non-specific small-bowel disease in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The mucosal disease caused by these drugs in the small bowel is termed NSAID enteropathy. The abnormalities of NSAID enteropathy include inflammation, erosion, fibrosis, stricture, perforation, and formation of diaphragm disease. The most frequent manifestations are iron-deficient anemia, acute hemorrhage, perforation and obstruction of the small bowel. Many studies have reported cases with multiple diaphragm-like strictures in the whole gastrointestinal tract that are associated with the chronic use of NSAIDs[2-6]. In contrast, from the references we can find, only one reported case with small bowel diaphragm disease is not associated with the use of NSAIDs[7]. Multiple diaphragm-like strictures emerged in the ileum and jejunum at different times in this patient and he underwent three surgical operations.

Here, we report on a group of 5 patients who presented symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and characteristics of diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel that were not attributable to the utilization of NSAIDs. The purpose of this study was to summarize the clinical, radiologic, endoscopic and pathologic features of these special diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel.

This work has been carried out after receiving the approval from our institutional review board. All patients were not individually asked for consent to be included in this study, but each patient in the study did agree to the retrospective use of their medical records and images for research purposes during treatment at our hospital.

From cross-referenced records in the Departments of Gastroenterology, Radiology and Pathology at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, from January 2000 to December 2009, 5 patients were identified with clinically confirmed diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel. All the 5 patients denied the use or prescription of NSAIDs, which was confirmed by their family members and medical history records. These 5 patients included two men and three women. Clinical data from the patients including sex, age, hemoglobin level, white blood cell (WBC) count, C-reactive protein (CRP) level and major onset symptoms were obtained from the hospital database and most information is shown in Table 1. All cases underwent removal of the lesions by laparoscopically assisted enterectomy.

| Case | Sex | Age at onset(yr) | Age at diagnosis(yr) | Past history | Main symptoms | Physicalexamination | HGB(g/dL ) | WBC count(×109/L ) | |

| GI bleeding | Abdominal pain | ||||||||

| 1 | F | 30 | 33 | Gallbladder stone | P | P | Normal | 9.0 | 3.2 |

| 2 | F | 48 | 64 | No | P | Normal | 5.8-9.6 | 4.1 | |

| 3 | M | 24 | 26 | Appendectomy | N | Normal | 10.9 | 5.3 | |

| 4 | F | 40 | 44 | Hysteromyoma | P | P | Normal | 9.2 | 5.7 |

| 5 | M | 32 | 41 | No | P | N | Normal | 9.7 | 5.0 |

Capsule endoscopy (CE) was performed in 3 patients (cases 1, 2 and 5). The small bowel capsule, manufactured by Given Imaging (Yoqneam, Israel) measures 11 mm × 26 mm and weighs 3.7 g. The camera in the capsule moves through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract via peristalsis and transmits 2 images per second to a data recorder located on the waist of the patient.

All 5 patients underwent double-balloon endoscopy (Fujinon, En-450P5/20, Fujinon Inc, Saitama, Japan). When the location of the lesion could be predicted in advance by the color of the feces or other examination findings, an insertion approach close to the lesion was selected, either oral or anal. When the location could not be predicted, the anal approach was selected first, in principle. However, whether the responsible lesion was specified or not by the first insertion approach, insertion with the other approach was performed later to observe the entire small bowel.

All the images were reviewed by two gastroenterologists who had no knowledge of the final radiologic, endoscopic, or pathologic findings. The endoscopic evaluation included number, location, size, shape, color and texture.

Routine abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in one patient. CT enterography (CTE) was performed in all five patients. For CTE examination, all patients underwent an intestinal preparation according to the following plan: the day before a light diet free of fruit and vegetables; 500 mL of a mixture of Sennosides and tea at 5:00 pm, another 500 mL followed at 6:00 pm. All patients accepted oral administration of 2.5% mannitol solution (1500-2000 mL) over 30-45 min. Thirty minutes after oral administration, CT scans were performed on a multi-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scanner [two patients had scans performed on a 16-slice MDCT scanner (LightSpeed-16, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and the other three patients were on a 64-slice MDCT scanner (LightSpeed Volume CT, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI)]. Section thickness ranged between 5 mm and 7.5 mm. Intramuscular injection of 20 mg anisodamine was administered 10 min before CT scan. After unenhanced CT scan, all patients received an intravenous injection of 1.5 mL/kg of iohexol (Omnipaque300; Amersham, Shanghai, China) at a rate of 3 mL/s. Contrast-enhanced CT images were acquired in arterial phase (25-30 s) and venous phase (60-65 s). Multiplanar reconstructions and maximum intensity projection were performed at the workstation (ADW4.2 and ADW4.4).

In addition, small-bowel follow-through (SBFT) was performed in 3 patients (cases 2, 4 and 5). Selective mesenteric angiography examination and bowel isotope scans using 99mTc-labeled red blood cells (99mTc-RBC) were also performed for case 2.

The radiologic images were reviewed in consensus by two radiologists who had no knowledge of the final endoscopic, radiologic, or pathologic results. At the workstation, the CT images from each patient were reviewed to analyze the following criteria: (1) location of lesion; (2) number of lesions; (3) thickness of bowel wall; (4) lumen cavity; (5) mesenteric vessels; and (6) lymph nodes. At non-enhanced CT, attenuation in the lesions was classified as hypodense, isodense, or hyperdense compared with the normal bowel wall. After contrast enhancement, the degree of enhancement was classified into no enhancement, mild (10-20 Hu), moderate (20-50 Hu), or marked (> 50 Hu) enhancement. These findings were used to characterize the imaging and the gross pathological features of the lesions.

All the specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formaldehyde solution and were embedded in paraffin wax. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed in all the pathologic specimens. All the pathologic specimens were reviewed retrospectively by two pathologists. The macroscopic appearances of each resected segment were analyzed with photomacrographs; the analysis included number, location, size, shape depth and edge.

All the 5 patients presented long-term (2-16 years) symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding (hematochezia appeared in case 4 and intermittent black stools occurred in the other four patients) and varying degrees of anemia, accompanied by obscure abdominal pain in three patients (cases 1, 2 and 4) (Table 1) and incomplete intestinal obstruction in one case. No significant changes were detected on physical examination, gastroscopy and colonoscopy. Three patients (cases 1, 2 and 3) were suspected of having small bowel Crohn’s disease and received mesalazine medication. However, this medication was ineffective in these cases. In addition, administration of hemostyptic agents and iron supplementation eliminated bleeding and improved the condition of all patients. Three lesions were detected in case 2 and the remaining 4 cases had one lesion in the ileum. WBC count was not elevated and the proportion of eosinophils did not increase in all cases. One patient had a CRP level test with normal result. All cases had removal of the lesions by laparoscopically assisted enterectomy and remained well at 1 to 3.5 years follow-up with no signs of gastrointestinal bleeding.

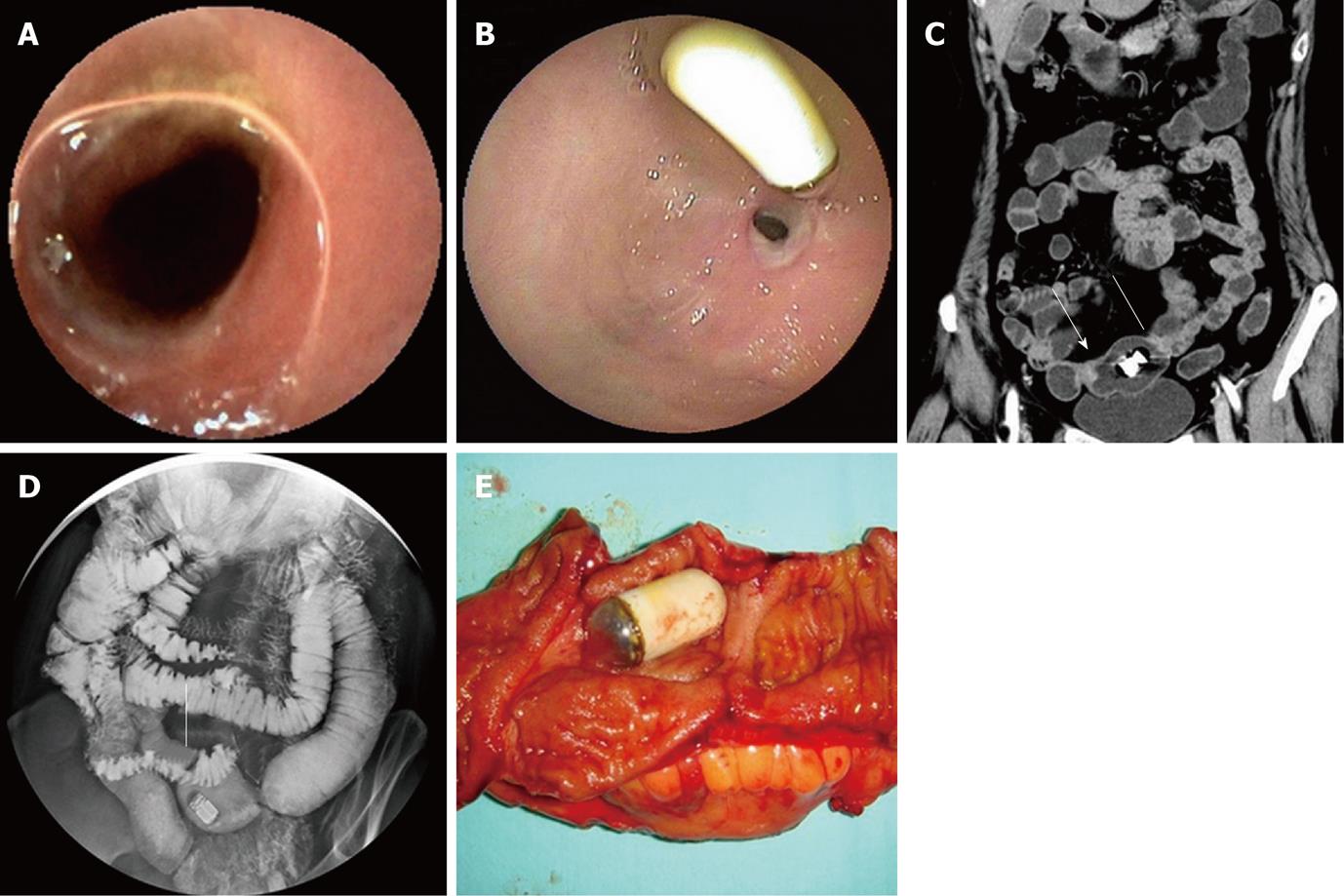

On the images of capsule endoscopy, a mild circumferential stricture in the ileum was shown in two lesions which the capsule could pass through (Figure 1A). In another two cases, the capsule was stopped by markedly circumferential stricture of the lumen.

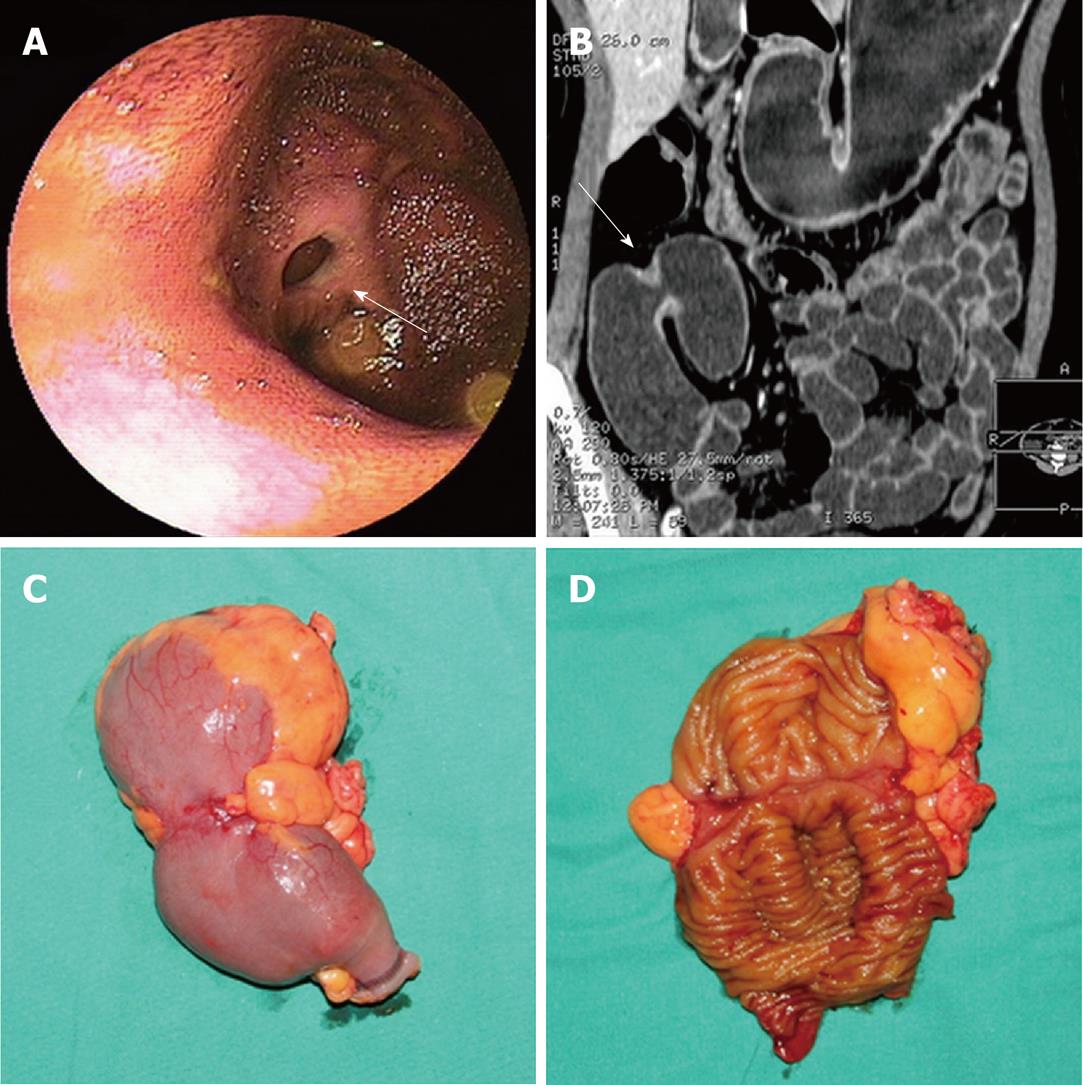

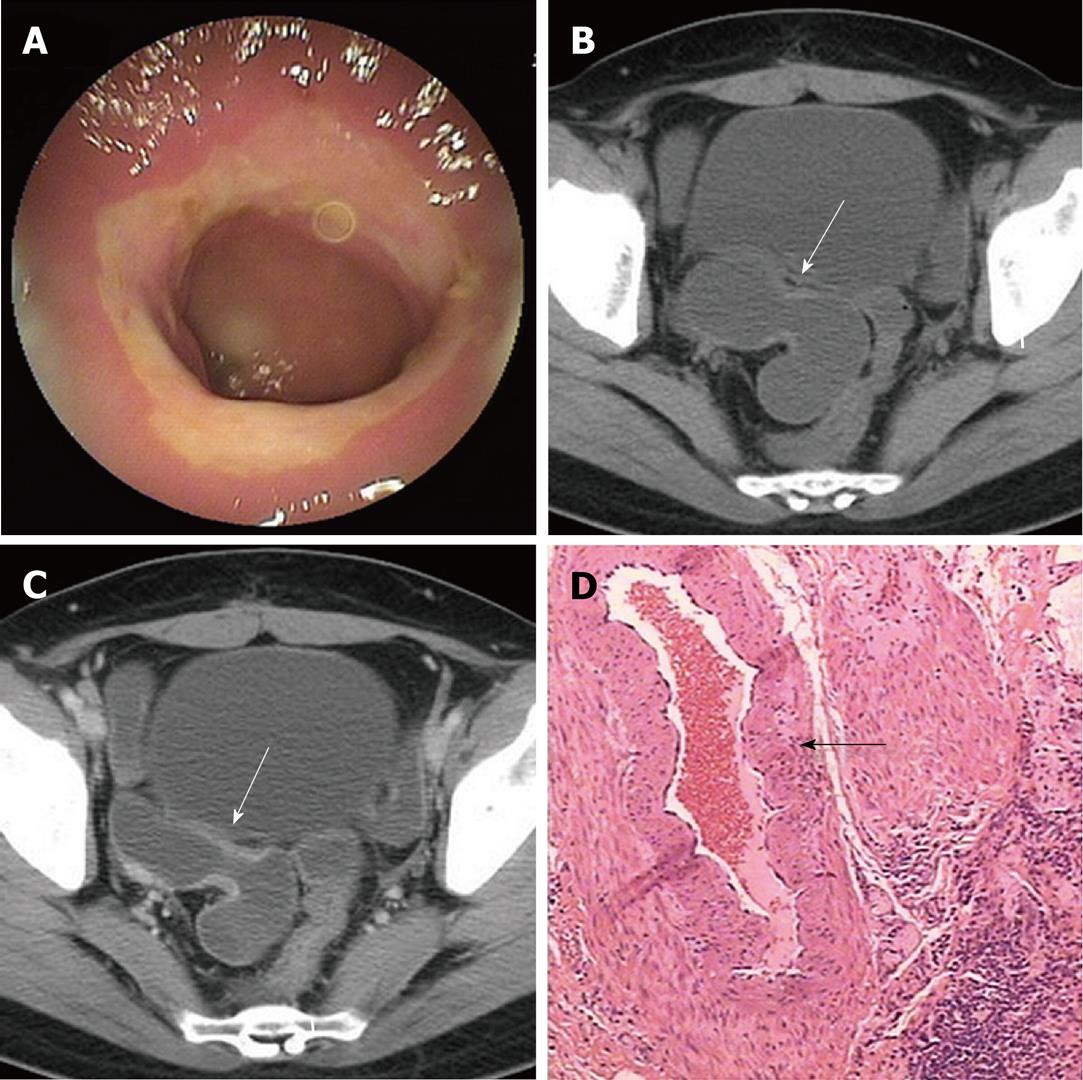

All the 7 strictures in five patients were found in the double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) examination undergone by all five patients. All lesions appeared in the middle or distal segment of ileum which was about 80 cm to 150 cm away from the ileocecal valve and the scope could pass through. Circumferential ulcers or erosions with clear margin on the surface of stenoses were found in all lesions. All ulcers were covered by faint white mucous exudates. Congestion and edema in the neighboring mucosa and dilated small bowel loop adjacent to the stricture were also observed in all lesions (Table 2, Figure 1B, 2A and 3A).

| Case | n | Location (distance to ileocecal valve)(cm) | Type of lesion | Stricture | Edema in mucosa | Pass-through of scope | |

| Mild to moderate | Severe | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 80 | Ulcer | 1 | 0 | P | P |

| 2 | 3 | 100-115 | Ulcer and erosion | 1 | 2 | P | P |

| 3 | 1 | 100 | Ulcer | 1 | 0 | P | P |

| 4 | 1 | 80 | Ulcer | 1 | 0 | P | P |

| 5 | 1 | 150 | Erosion | 0 | 1 | P | P |

Routine abdominal CT scan was performed in only one patient and showed no other abnormal results except gallstones. The main features of diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel seen at CTE include thickening of bowel wall, circular stricture in the middle or distal segment of the ileum and dilated small bowel loop adjacent to the stricture. These features were observed in three patients. In case 2, only two out of three lesions were detected by CTE. A minor stricture could not be shown. In case 3, CTE could only show the thickened bowel wall, the significant dilated small bowel loop and several enlarged lymph nodes. However, the stricture was not shown in CT images. Bowel wall thickening appeared as mild, symmetrical isodensity with respect to the normal bowel wall with homogenous and moderate contrast enhancement. The thickened wall ranged from 2.5 mm to 5.0 mm in thickness and reached 7.0 mm in one lesion (case 2) which turned the lumen into a tight stricture and caused retention of the capsule. The diameter of the lumen in the dilated small bowel loop ranged from 2.7 cm to 5.0 cm in 4 patients and reached 7.0 cm in one case (Table 3, Figure 1C, 2B, 3B and C). There was no abnormality in the mesenteric vessels.

| Case | Location | n | Stenosis | Lumen expansion | Bowel wall | Mesentericvessels | Lymph nodeenlargement | ||

| Thickness (mm) | Attenuation | Enhancement | |||||||

| 1 | Ileum | 1 | P | P | 2.5 | Isodense | Moderate | Normal | N |

| 2 | Ileum | 2 | P | P | 7 | Isodense | Moderate | Normal | N |

| 3 | Ileum | 1 | N | P | 3 | Isodense | Moderate | Normal | P |

| 4 | Ileum | 1 | P | P | 2.5 | Isodense | Moderate | Normal | N |

| 5 | Ileum | 1 | P | P | 5 | Isodense | Moderate | Normal | N |

SBFT was performed in 3 patients (cases 2, 4 and 5). Two strictures in case 2 and 1 stricture in case 5 with dilated bowel loop were observed (Figure 1D). The pass-through of barium was blocked and stenoses of the lumen were still at the fixed location at a later time point observation after compression. Capsules floated in the dilated small bowel loops and could not move to the bottom with the downward movement of barium. Selective mesenteric angiography was performed in case 2 and showed no positive findings. One bowel isotope scan using 99mTc-RBC revealed intestinal bleeding in the distal ileum.

On gross examination, circumferential strictures were found in all the lesions of the resected small intestine in all five patients. These strictures were perpendicular to the long axis of the intestine. The lesions appeared as laterigrade diaphragms with laterigrade pittings in the mucosa, 0.2 cm to 0.5 cm in width, with edema in the neighboring mucosa in the longitudinal section of the specimens in four lesions from four patients (cases 1, 2, 3 and 4) (Figure 1E, 2C and D). They were approximately 0.5 cm in width in case 5 and in two lesions of case 2. Edema in the neighboring mesentery and enlargement of several lymph nodes were found in case 3. No abnormality was shown in the adjacent mesentery in the other cases. On microscopy, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate was found in all five subjects. Depth of ulcer reached to the muscularis propria in local areas in cases 1 and 2. The ulcer was limited to the submucosa in cases 3 and 4. Villous adenomatous hyperplasia in the mucosal layer was found in case 5 and in two lesions of case 2. Moderate local inflammatory cell infiltration was found in the submucosal layer of cases 1, 5 and two lesions of case 2. Inflammatory cell infiltration was obvious and reached to the serosa in cases 3, 4 and one lesion of case 2. Fibrosis in the submucosal layer was mild in cases 1 and 2 and moderate in cases 3 and 4 (Table 4). The rupture of the muscularis mucosa under the ulcer was also found in case 3. Specifically, proliferation of blood vessel with thick wall and expanded lumen appeared in the submucosa and distorted muscularis propria in two cases (cases 3 and 4) (Figure 3D). Granulomatous lesion was not found in any patient. No cytomegalic inclusion associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was found in any lesion.

| Case | Size1 (cm) | Type | Depth1 | Inflammatoryinfiltrate | Fibrosis | Mucosalatrophy | Thickening ofmuscularis mucosa | Edema insubmucosa |

| 1 | 2.0 × 0.5 | Ulcer | Muscular layer | Moderate | Mild | N | Mild | N |

| 22 | 2.0 × 0.2 | Ulcer | Muscular layer | Severe | Mild | N | Moderate | N |

| 3 | 3.0 × 0.2 | Ulcer | Submucosa | Severe | Moderate | N | N | P |

| 4 | 3.0 × 0.5 | Ulcer | Submucosa | Severe | Moderate | N | Moderate | P |

| 5 | 2.0 × 0.5 | Erosion | Mucosa | Moderate | None | N | N | N |

This retrospective study showed the clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features of distinctive small bowel diaphragm-like strictures. All patients presented with long-term (2-16 years) symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and varying degrees of anemia. All cases were not associated with the use of NSAIDs and had similar clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features.

The cause of these special diaphragm-like strictures remains uncertain. Diaphragm disease induced by NSAIDs characterized by inflammatory strictures of the small intestine has previously been recognized as an uncommon complication of NSAID enteropathy[1]. The abnormalities of NSAID enteropathy include inflammation, erosion, fibrosis, stricture, perforation, and formation of diaphragm disease. Diaphragm disease most frequently affects the ileum. It can also affect the jejunum and colon, as well as stomach and duodenum. There are usually multiple diaphragms. The depth of ulcer is restricted to the submucosal layer and it never extends to the proper muscular layer[1-6]. Improvement in clinical findings (signs and symptoms) and/or endoscopic findings appears on cessation of NSAID utilization, except for diaphragm disease. Diaphragm disease coupled with the use of NSAIDs is a pathognomic feature of NSAID enteropathy because of its non-specific histological findings[1-6]. Regarding clinical manifestations, the imaging findings in this study group share some common features with those observed in NSAID enteropathy, namely, concentric stenosis and circular ulcers. Diaphragm-like strictures in our study group are, however, different to those induced by NSAIDs with regard to many aspects such as the location, number, fibrosis and the disease process (Table 5).

| History | Location | n | Fibrosis | Lesions in other area ofbowel | Disease process | |

| Diaphragm disease | Long term NSAID use | Whole GI tract, most frequently in ileum | Multiple | Obvious | Exist, can be inflammation, erosion, fibrosis, stricture and perforation | Improvement in clinical findings by cessation of NSAID utilization |

| Diaphragm-like strictures | No NSAID use | Middle or distal segment of ileum | Usually single, no more than three | Mild or moderate | No | Non-self-limiting |

Santolaria et al[7] reported a male patient with diaphragm disease who had a 25-year history of relapsing abdominal pain and edema and who did not have long-term use of NSAIDs. However, the symptoms and history of this case were different to those in our group. Shimizu et al[8] reported a case with diaphragm-like stricture of the small intestine related to CMV infection. Multiple erosions and small ulcers in the ileum and a circumferential diaphragm-like stricture were seen in this patient, with increased C-reactive protein level, and a cytomegalic inclusion was found in the strictured lesion on biopsy. CMV infection usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients. In our group, immune response of all patients was normal and no cytomegalic inclusion was found in pathology findings. Pasha et al[9] reported a case with eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) mimicking diaphragm disease of the small bowel. Multiple ulcerated stenoses were present and capsule retention occurred in this case. Mucosal eosinophilia (> 20/HPF) can be found in EGE cases, usually accompanied by increased level of peripheral blood eosinophil count, signs which were not found in our group. Specifically, dilated blood vessel with thickened wall appeared in the submucosa in two cases in our group. This was different to angiodysplasia or hemangioma, in which the dilated blood vessel usually has a thin wall. Moreover, the manifestations of CT angiography in arterial phase and DBE also excluded the existence of vascular malformation. The history and pathologic examination of the lesions also excluded other potential causes of intestinal strictures, including use of potassium chloride tablets, surgical anastomoses, radiation, ischemia, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, and lymphoma.

Diaphragm-like strictures can also be found in the small bowel in congenital cases in adults, though this is rare. Congenital atresias, diaphragm-like strictures or stenoses are well documented occurrences in the stomach, duodenum and small bowel. Small intestinal atresia/stenosis most frequently affects the duodenum, followed by the jejunum, and least often the ileum, and can affect multiple sites of the intestine[10-16]. Intestinal obstruction is described as the main symptom. Cases that occur in the ileum and lead to bleeding of the small bowel have not been found in the literatures. All seven diaphragm-like strictures of the five cases were found in the middle or distal segment of the ileum in our group. It may be possible that congenital diaphragm-like stenoses may firstly have existed in the ileum, inflammation and ulcers then occurring after a long-term limitation of intestinal motility in the stenoses and friction between food and stenoses. This could explain why there was only one lesion in most cases, the stricture was obvious even if there was no marked fibrosis in the lesion, and the symptoms disappeared after operation. However, more evidence is needed to test this hypothesis.

Diagnosis of special diaphragm-like strictures of small bowel in non-NSAID patients may be difficult. No significant findings were detected on physical examination. Routine abdominal CT scan in general could not show any abnormal results. CE, DBE, CTE and SBFT may be helpful in making a diagnosis and may facilitate preoperative evaluation of the lesions. CE has been mainly used to evaluate patients with obscure GI bleeding[17]. There have also been many reports demonstrating diaphragm-like strictures in CE examinations[18-20]. Sometimes, diaphragms may be misinterpreted as exaggerated plicae circulares. CE carries a risk of obstruction in patients with tight stenoses. Therefore, it should not be used if a stricture is present. DBE may show circumferential diaphragm-like strictures with ulcers or erosions. DBE has been used to successfully diagnose diaphragm disease in patients with GI bleeding and ileus in many literature reports[21-23]. DBE can also be used for treatment of the diaphragm disease[22,23]. As there are no specific pathological changes, endoscopic biopsy could not help much in the diagnosis. Three patients in our study group were initially suspected of having small bowel Crohn’s disease. CTE can show thickening of bowel wall, dilated small intestinal loops and circular or diaphragm-like strictures. CTE can also show the adjacent mesentery, mesenteric vessels and lymph nodes, which could help to exclude other potential causes of intestinal strictures[24-27]. Adequate distension of the entire small intestine is crucial to display the lesions. It must be mentioned here that it is necessary to combine CTE with other inspections such as SBFT or DBE to make a correct diagnosis. This is due to the fact that the images of CT are static and may misinterpret the lesion as plicae circulares especially when the bowel lumen is not distended completely. SBFT can show diaphragm-like strictures with dilated small bowel loop in the adjacent segment. The diaphragm lesions are thin and do not distort the bowel wall[28]. The greatest advantage of SBFT is its dynamic view of the small intestine motility. The diaphragms which are not shown distinctly might be misinterpreted as exaggerated plicae circulares[3]. Mesenteric angiography may have no positive findings, which implies that the symptom of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding is not caused by mucosal vascular abnormalities or vasculitis, etc. Bowel isotope scan may be not informative and may only reveal the intestinal bleeding. Though there are many imaging examinations to help make a diagnosis, in some cases surgical intervention might be necessary to make the definitive diagnosis.

Our study had several limitations. For example, the sample size is small due to the rarity of the disease. It is meaningless to conduct statistical analysis for this small number of cases. In addition, the cases were a select surgical series which had radiological and/or endoscopic presurgical work-up. Obviously, non-surgical cases and those patients who did not have imaging or endoscopic work-up would have been excluded.

Although the number of subjects was small, our results indicate that special diaphragm-like strictures characterized by ulcers and circular stenosis can also occur in the small intestine in patients without the use of NSAIDs and might be a special consequence of unclear damaging insults to the intestine. They have similar clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features. The diaphragm-like strictures tend to be intractable because this is a non-self-limiting condition with little tendency toward mucosal healing. Currently, enterectomy of the diseased bowel segment is the only useful therapy. Clinicians should be aware that small-bowel diaphragm-like strictures might be a cause of chronic small bowel bleeding in patients receiving no NSAID therapy.

Thanks to Dr. Rui-Zhe Shen for the work of acquisition and analysis of the endoscopic data and to Mr. Xiao-Chun Fei for acquiring and analyzing the pathology data.

Diaphragm disease induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as inflammatory strictures of the small intestine, has previously been recognized as an uncommon complication in patients taking NSAIDs. The most frequent manifestations are iron-deficiency anemia, acute small-bowel hemorrhage and perforation, and obstruction of the small bowel. However, diaphragm-like strictures in the small bowel can also not be associated with the use of NSAIDs. Here, the authors illustrate a group of five patients presenting with bleeding of small bowel and in whom diaphragm-like strictures in small bowel were present that were not attributed to NSAID use.

Bleeding within the small bowel is often difficult to diagnose. Currently, the first diagnostic procedure in patients with small bowel hemorrhage is capsule endoscopy (CE) or double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE). CE has been mainly used to evaluate patients with obscure gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, but carries a risk of obstruction in patients with tight stenoses such as diaphragm-like strictures. DBE can show circumferential diaphragm-like strictures with ulcers or erosions and can also be used for treatment of the diaphragm disease. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning is establishing itself as a rapid, noninvasive, and accurate diagnostic method in gastrointestinal bleeding. Arterial phase CT scanning is an excellent diagnostic tool for fast and accurate detection and localization of GI hemorrhage. The combination of a variety of inspection methods can help to confirm the diagnosis.

The unique aspect of this study is that it is the largest series of intestinal diaphragm-like strictures which are not associated with NSAID use. To the best of our knowledge, there are still no descriptions about the imaging features of this disease in the English literature. The results indicate that special diaphragm-like strictures characterized by ulcers and circular stenosis can also occur in the small intestine in patients without the use of NSAIDs and might be a special consequence of unclear damaging insults to the intestine. They have similar clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features and tend to be intractable for this is a non-self-limiting condition with little tendency toward mucosal healing. Findings at endoscopic and radiologic imaging of this disease may help to make a diagnosis and facilitate preoperative evaluation of the lesions.

Small-bowel diaphragm-like strictures characterized by ulcers and circular stenosis might be a cause of chronic small bowel bleeding in patients without NSAID therapy and might be a special consequence of unclear damaging insults to the intestine. They have similar clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and pathologic features. The diaphragm-like strictures tend to be intractable because it is a non-self-limiting condition with little tendency toward mucosal healing. Currently, enterectomy of the diseased bowel segment is the only useful therapy.

Diaphragm disease is inflammatory strictures of the small intestine and is an uncommon complication of non-specific small-bowel disease, caused by mucosal and submucosal fibrosis and thickening in patients taking NSAIDs. Computed tomography enteroclysis (CTE) is to perform contrast-enhanced CT scanning and image post-processing after small intestine distension by administering a high volume of contrast medium into the small intestine orally or via a nasojejunal catheter. CTE can display the cavity and wall of small intestine, parenteral lymph nodes, mesentery, mesenteric vessels and the adjacent structures, etc.

In this study, the authors summarized the characteristics of diaphragm-like strictures of the small bowel without use of NSAIDs. Their report contained 5 cases and described the clinical, endoscopic, radiographic and pathologic features. Although there are many papers that have described diaphragm disease of the small bowel associated with NSAIDs, diaphragm disease unrelated to NSAIDs rarely exists in clinical settings. It is necessary to accumulate many more clinical cases to reveal the clinical significance of this disease phenotype. Although this report is preliminary as it stands, it might see the light in this field.

Peer reviewers: Mitsunori Yamakawa, Professor, Department of Pathological Diagnostics, Yamagata University, Faculty of Medicine, 2-2-2 Iida-Nishi, 990-9585 Yamagata, Japan; Satoshi Osawa, MD, First Department of Medicine, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, 1-20-1 Handayama, 431-3192 Hamamatsu, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 2:S88-S94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557-2576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3846] [Cited by in RCA: 4262] [Article Influence: 236.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Rampone B, Schiavone B, Martino A, Viviano C, Confuorto G. Current management strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3210-3216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ganslmayer M, Ocker M, Zopf S, Leitner S, Hahn EG, Schuppan D, Herold C. A quadruple therapy synergistically blocks proliferation and promotes apoptosis of hepatoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:943-950. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 823] [Cited by in RCA: 831] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ganslmayer M, Ocker M, Kraemer G, Zopf S, Hahn EG, Schuppan D, Herold C. The combination of tamoxifen and 9cis retinoic acid exerts overadditive anti-tumoral efficacy in rat hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;40:952-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pinter M, Sieghart W, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Maieron A, Königsberg R, Weissmann A, Kornek G, Plank C, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma from mild to advanced stage liver cirrhosis. Oncologist. 2009;14:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Richly H, Schultheis B, Adamietz IA, Kupsch P, Grubert M, Hilger RA, Ludwig M, Brendel E, Christensen O, Strumberg D. Combination of sorafenib and doxorubicin in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from a phase I extension trial. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:579-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fernández M, Semela D, Bruix J, Colle I, Pinzani M, Bosch J. Angiogenesis in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2009;50:604-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15-18. |

| 11. | Thomas AL, Trarbach T, Bartel C, Laurent D, Henry A, Poethig M, Wang J, Masson E, Steward W, Vanhoefer U. A phase IB, open-label dose-escalating study of the oral angiogenesis inhibitor PTK787/ZK 222584 (PTK/ZK), in combination with FOLFOX4 chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:782-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ellis LM, Rosen L, Gordon MS. Overview of anti-VEGF therapy and angiogenesis. Part 1: Angiogenesis inhibition in solid tumor malignancies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4:suppl 1-10; quz 11-2. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fang JY. Histone deacetylase inhibitors, anticancerous mechanism and therapy for gastrointestinal cancers. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:988-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herold C, Ganslmayer M, Ocker M, Hermann M, Geerts A, Hahn EG, Schuppan D. The histone-deacetylase inhibitor Trichostatin A blocks proliferation and triggers apoptotic programs in hepatoma cells. J Hepatol. 2002;36:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kummar S, Gutierrez ME, Gardner ER, Chen X, Figg WD, Zajac-Kaye M, Chen M, Steinberg SM, Muir CA, Yancey MA. Phase I trial of 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG), a heat shock protein inhibitor, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced malignancies. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:340-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qu W, Kang YD, Zhou MS, Fu LL, Hua ZH, Wang LM. Experimental study on inhibitory effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 and TSA on bladder cancer cells. Urol Oncol. 2009;28:648-654. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Liu Y, Poon RT, Li Q, Kok TW, Lau C, Fan ST. Both antiangiogenesis- and angiogenesis-independent effects are responsible for hepatocellular carcinoma growth arrest by tyrosine kinase inhibitor PTK787/ZK222584. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3691-3699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Clark JD, Gebhart GF, Gonder JC, Keeling ME, Kohn DF. Special Report: The 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 1997;38:41-48. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wong CM, Ng IO. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2008;28:160-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Matsuda Y. Molecular mechanism underlying the functional loss of cyclindependent kinase inhibitors p16 and p27 in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1734-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ocker M, Alajati A, Ganslmayer M, Zopf S, Lüders M, Neureiter D, Hahn EG, Schuppan D, Herold C. The histone-deacetylase inhibitor SAHA potentiates proapoptotic effects of 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan in hepatoma cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:385-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yao DF, Wu XH, Zhu Y, Shi GS, Dong ZZ, Yao DB, Wu W, Qiu LW, Meng XY. Quantitative analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular density and their clinicopathologic features in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:220-226. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Hauschild A, Trefzer U, Garbe C, Kaehler KC, Ugurel S, Kiecker F, Eigentler T, Krissel H, Schott A, Schadendorf D. Multicenter phase II trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor pyridylmethyl-N-{4-[(2-aminophenyl)-carbamoyl]-benzyl}-carbamate in pretreated metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:274-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang XF, Qian DZ, Ren M, Kato Y, Wei Y, Zhang L, Fansler Z, Clark D, Nakanishi O, Pili R. Epigenetic modulation of retinoic acid receptor beta2 by the histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 in human renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3535-3542. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Muto Y, Moriwaki H, Saito A. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1046-1047. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Aldana-Masangkay GI, Sakamoto KM. The role of HDAC6 in cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:875824. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Boudiaf M, Jaff A, Soyer P, Bouhnik Y, Hamzi L, Rymer R. Small-bowel diseases: prospective evaluation of multi-detector row helical CT enteroclysis in 107 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2004;233:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zalev AH, Gardiner GW, Warren RE. NSAID injury to the small intestine. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |