Published online Aug 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3580

Revised: August 18, 2010

Accepted: August 25, 2010

Published online: August 21, 2011

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a widely accepted treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC), especially in Korea and Japan. The criteria for the therapeutic use of ESD for EGC have been expanded recently. However, attention should be drawn to the technical feasibility of the ESD treatment which depends on a lesion’s location, size or fibrosis level, or operator’s experience. In the case of a lesion with a high level of difficulty, a more experienced operator is required. Thus, the treatment for a lesion with a high level of difficulty should be performed according to the degree of the operator’s experience. In this paper, the authors describe the ESD procedure for lesions with a high level of difficulty.

- Citation: Kim KO, Kim SJ, Kim TH, Park JJ. Do you have what it takes for challenging endoscopic submucosal dissection cases? World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(31): 3580-3584

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i31/3580.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3580

Recent advances in endoscopic technology, the accumulation of vast amounts of surgical data regarding the lymph node status in early gastric cancer (EGC), and increasing operator experience in the endoscopic treatment of EGC have made endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) a widely acknowledged standard curative therapy for EGC[1-3]. Nonetheless, not only the histology type and lesion size but also the anatomical location must be considered in deciding whether ESD is suitable for the lesion[4,5]. Generally, ESD is difficult to perform when patient cooperation is poor (because of severe belching or vomiting); when an anatomical deformity of the stomach (due to gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia or a previous stomach operation) makes sufficient stomach inflation difficult; when the patient is in a poor condition (old age, cardiopulmonary comorbidities, patients taking anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents); and when the lesion is located at a place where endoscopic access and submucosal dissection are difficult (cardia, high body, fundus, pylorus, and duodenum). Of these factors, an anatomically difficult location is the most common factor that makes the procedure difficult even for experienced endoscopists. This review is thus focused on ESD for an anatomically difficult lesion. This article is part of a series of reviews on ESD.

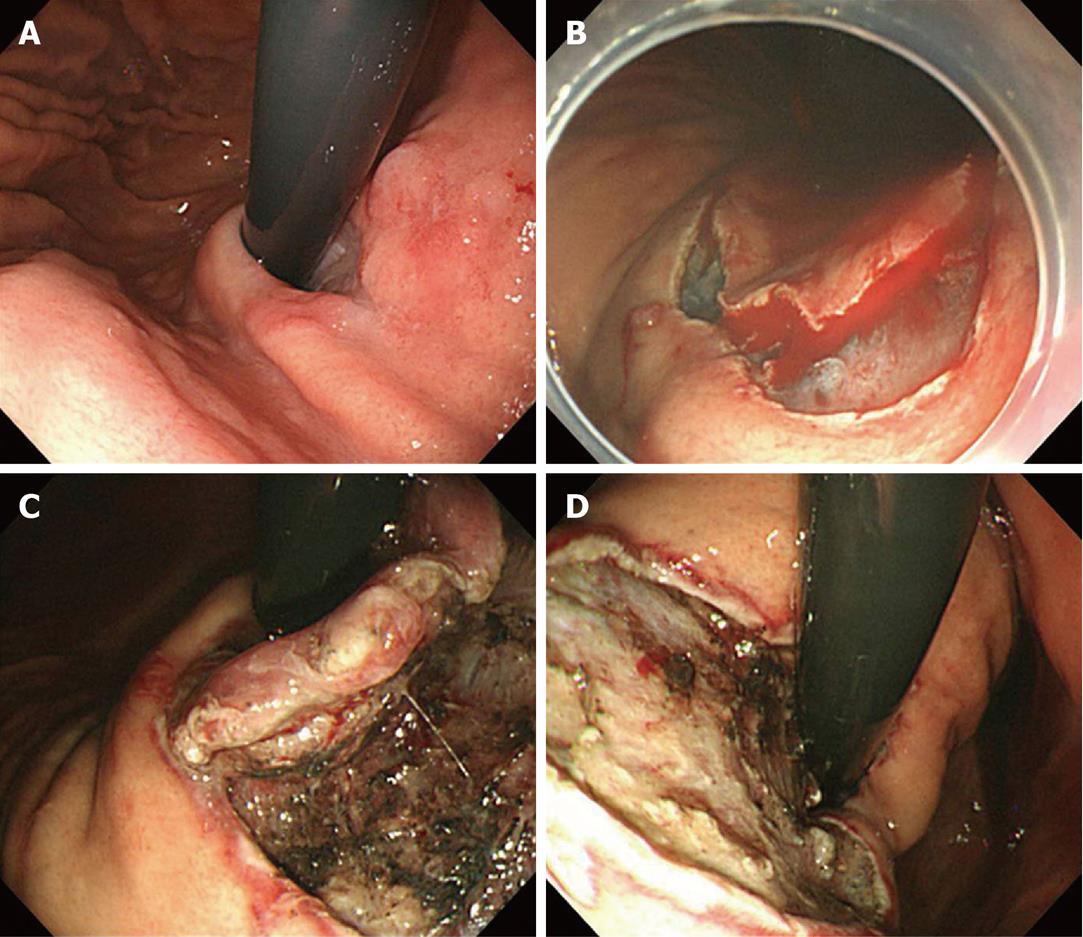

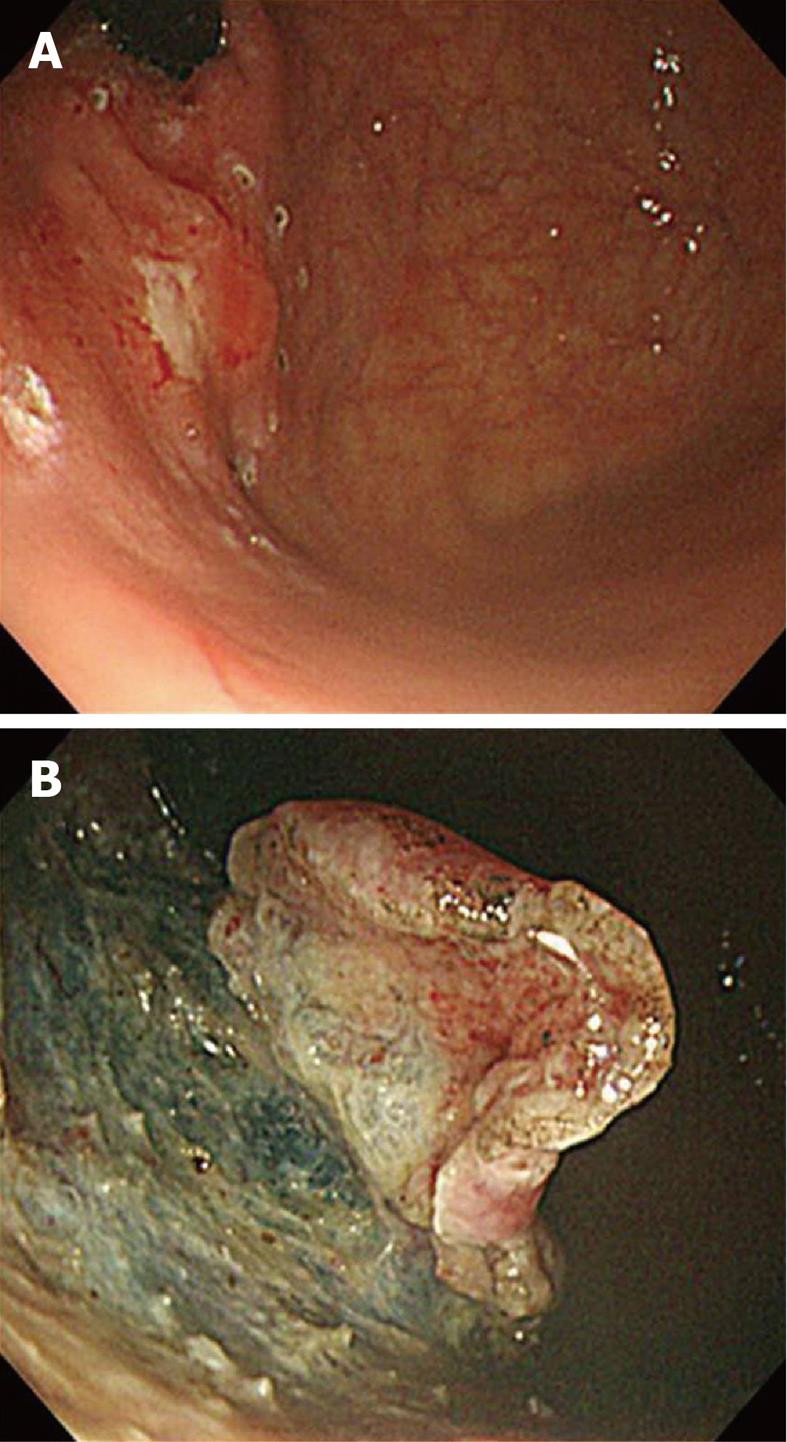

The cardia and gastroesophageal (GE) junction are susceptible to bleeding and perforation due to their abundant submucosal vasculature and thin walls. Regarding the cardia, the approaching angle is acute, and the lumen is narrow at the GE junction (Figures 1 and 2). When performing a mucosal incision at the margin, it is easier when the endoscope is retroflexed and when the incision is initially cut from the oral to the anal side of the esophagus. While dissection of the esophageal lesion is being performed, the region of dissection must be carefully watched as the esophageal wall lacks a serosa layer and has a thin muscle layer.

An insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife (IT knife) makes cutting easy and safe. When dissecting the lesion from the stomach, it is important for the flap of the lesion made by gradual dissection to be maximally turned over by gravity. Normally, the finishing is performed under retroflexion view, but when using an IT knife, it may be easier to straighten the endoscope at the GE junction and then to make the final cut.

When performing ESD for a lesion located in the body of the stomach, the endoscopist has to be very cautious to prevent bleeding and perforation especially in the high body. Therefore, the endoscopist has to make sure that a sufficient visual field is secured through precoagulation. To guarantee a good visual field, the endoscopist has to bear in mind that the direction of the incision should not be disturbed by unpredictable bleeding in a blind fashion. For larger vessels, precoagulation with hemostatic forceps is needed to avoid uncontrolled bleeding during the procedure. It is also essential to understand the anatomical characteristics of this particular area for a successful and safe procedure. In the deepest muscular layer of the stomach body, especially in the anterior and posterior wall sides, lie the medial longitudinal oblique muscles, where the perforating vessels form a network. Along with this transverse vasoganglion, the attached fibrous tissue forms a so-called “myofascial layer”. The fibrotic nature and abundant vasculature of this layer explain why the cutting and dissection of the high body anterior and posterior walls are difficult. Just beneath the transverse vasoganglion (i.e. just above the muscular layer), there is a layer with less vessels and fibrotic tissue. Performing the dissection in this layer is the key point to easy and safe ESD. In dissection, cutting through the above-mentioned vessel network can cause problems due to bleeding. In this situation, the simple maneuver called “coagulation mode trimming” is useful. During this maneuver, the endoscopist uses an IT or flex knife, which is moved back and forth to both coagulate the vessels and dissect through the transverse vasoganglion. Once the mucosa is cut to an adequate depth, the endoscopist should follow the general principles of the procedure. These include maintaining a good visual field of the submucosa, prophylactic coagulation of the visible vessels, and dissection with a curved movement along the direction of the gastric wall through the appropriate handling of the endoscope. In contrast to the anterior and posterior walls of the high body, the lesser curvature of the body has less perforating branches and fibrotic submucosa, which generally makes dissection easier. During the ESD procedure for a lesion in the lesser curvature of the body, precoagulation using Coagrasper hemostatic forceps is required to prevent bleeding because damage to the large blood vessels emerging from the muscle layer caused by an electrosurgical knife may induce massive bleeding.

The high body can have a normal external protrusion beside the adjacent organs, such as the liver. The muscle layer can be regionally elevated, and dissection would have to be made in a curved line to overcome the perpendicular angle between the cutting knife and the muscle layer. Without sufficient visualization of the field, the chance of perforation is high.

The difficulty of performing ESD for a fundal lesion lies in the limited visual field because of the stomach contents, blood retention due to gravity, movement of the lesion via respiration or heartbeat, and the thin muscle wall in the fundus compared to other parts of the stomach. Nevertheless, when the lesion is located obliquely in between the fundus and the anterior or posterior wall of the high body, an experienced endoscopist can dissect the lesion with an IT knife (Figure 2). For lesions that can be seen only when the endoscope is turned around, and when the lesion is located at the greater curvature side between the cardia and the fundus, ESD is generally impossible to perform. When the lesion is relatively small and cutting around its edge is possible, the removal of the lesion by snare can be an alternative treatment option.

For fundal lesions, because of this highest level of difficulty, ESD is usually not recommended.

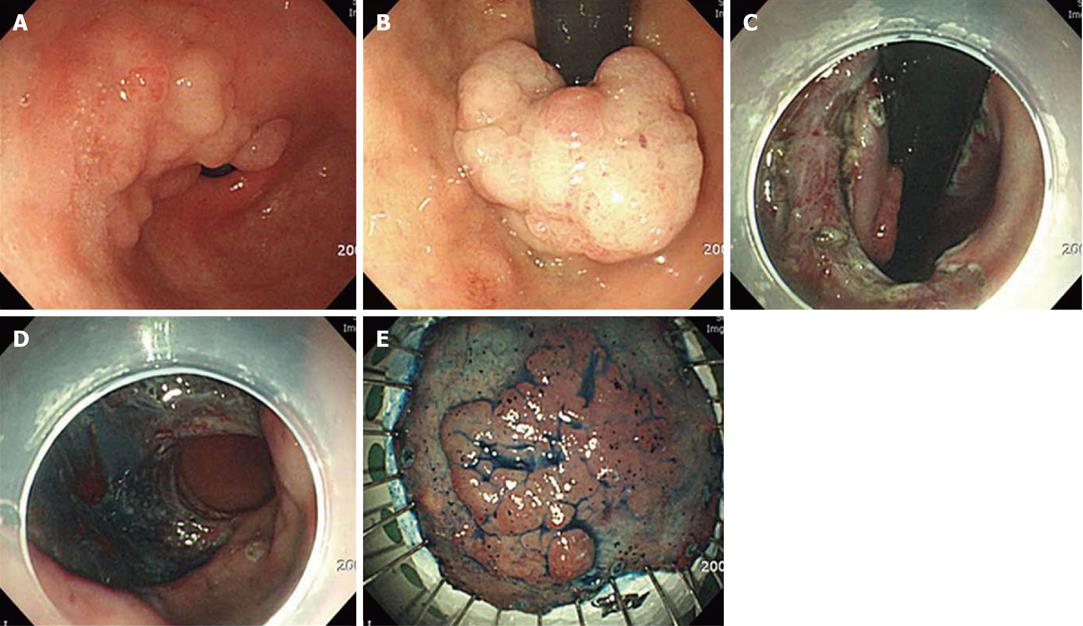

The incidence of ESD performance for a pyloric lesion has recently been increasing, but actually reported cases are still rare. When the distal part of the lesion is located at the pyloric channel, the incision and cutting should start from the proximal part, i.e. the antrum. As the dissection progresses and when the pyloric channel is reached, the flap can be pushed into the bulb by the tip of the endoscope, which exposes the muscle and bottom layers of the lesion. With sufficient submucosal injection, the remainder of the lesion can be cut using a needle knife if the distal margin is confined to the channel ring, and if a clear margin can be assured. In the case of the pyloric lesion extended to the duodenal bulb, the endoscope has to be retroflexed gently at the duodenal bulb, and the dissection incision should be started from the duodenal distal end (Figure 3). Through this maneuver, a safe distal margin can be secured, but when there is an anatomical deformity of the bulb, a reverse turn of the endoscope may not always be possible, and there is a risk of perforation during the dissection of the pyloric channel. Therefore, in the event of such a case, after the distal margin in the bulb is first dissected using a retroflexed endoscope, the endoscope is straightened for the dissection of the remaining proximal margin at the antrum and for the completion of the procedure.

The duodenal wall is highly susceptible to perforation if the submucosal injection is not sufficient because mucosal and muscle layers of the duodenal wall are very thin in contrast to that of the gastric wall. Thus, great care must be taken to make an incision of the mucosal layer not too deep after sufficient submucosal injection.

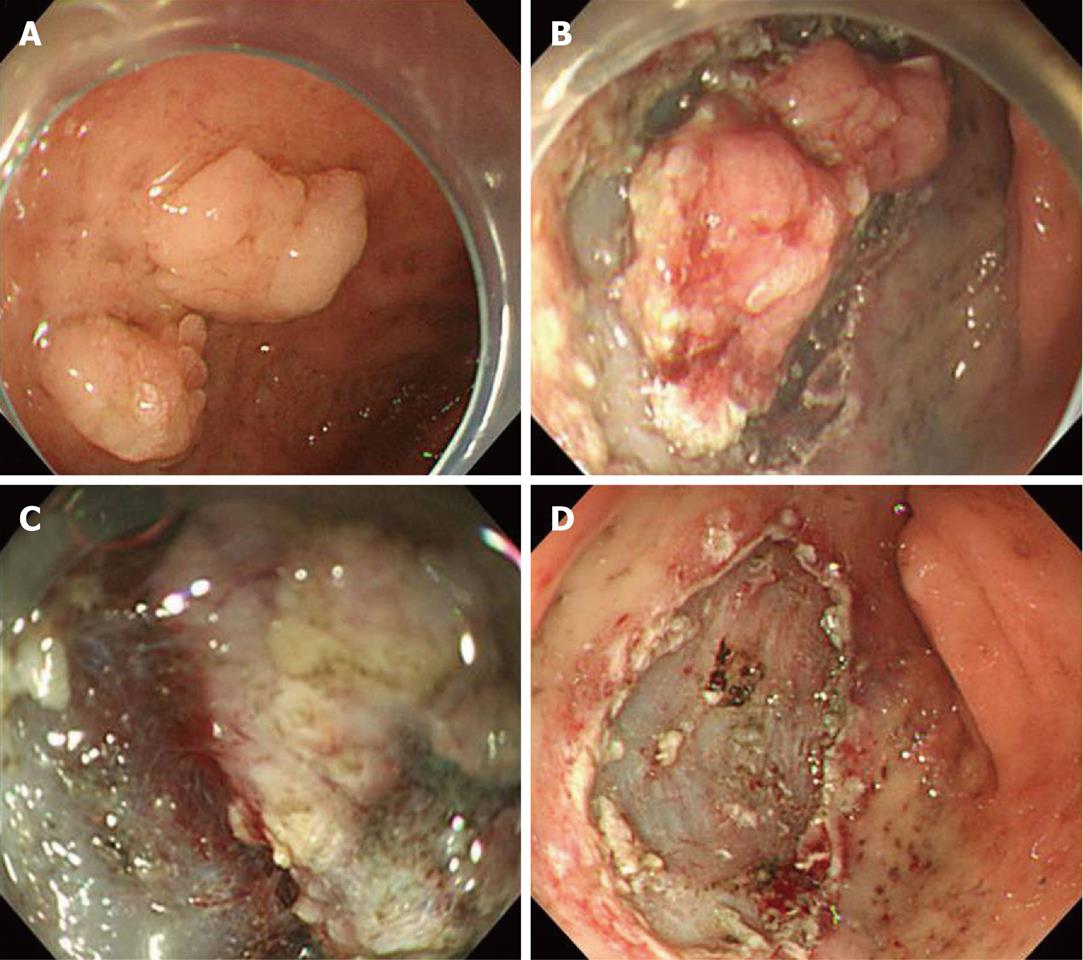

Performing ESD for a duodenal lesion is much more challenging than performing it anywhere else because of the insufficient mucosal elevation and poor mucosal contraction. Moreover, the abundant vasculature in the submucosal layer, and the thin muscle layer, make the procedure very vulnerable to bleeding and perforation[6]. If the patient is uncooperative, it will be very hard to maintain the endoscope close to the lesion, especially at the second portion, because of the movement via respiration and belching. Therefore, it is very common for an endoscope inserted into the second portion to slip out to the bulb or the antral portion while being pulled with a needle or IT knife during incision or dissection. Thus, in such situations, the use of a hook knife is more ideal. It is also important for the assistant to get a firm grip of the endoscope during the procedure. On account of these difficulties, the endoscopic treatment of duodenal lesions has been limited to polypectomy or mucosal resection using the endoscopic mucosal resection C or EMR sodium hyaluronate methods, and the performance of real ESD has been very rare. The thin submucosal layer, which has the unique anatomical characteristics of the duodenum, makes sufficient “cushion” formation after the submucosal injection difficult (Figure 4). Moreover, mucosal contracture after precutting does not occur as easily as in the other parts of the stomach. Therefore, submucosal dissection just above the muscle layer is an alternative solution for performing duodenal ESD.

As regards the level of difficulty of ESD procedures, the fundus is the region with the highest level of difficulty. The fundus is the most difficult area on which to perform an ESD procedure because approach is difficult, the gastric wall is thin, and it is adjacent to the diaphragm. For the duodenum, it is impossible to perform an ESD procedure except on some portions of the bulb. Moreover, endoscopists other than highly experienced experts should avoid performing ESD procedure on the bulb. The easiest area on which to perform ESD is the antrum where even novices can perform an ESD procedure.

In this article, ESD for an anatomically difficult lesion was briefly discussed. The result of the procedure varies based on the endoscopist’s skill, the size of the lesion, the type of device used, and even the coagulation mode employed. This means that there is no such thing as “a magic bullet” for a difficult ESD. The recent development of the multibending and “R” scopes and of many other devices will hopefully help overcome the aforementioned difficulties, and further studies on this subject are needed. Training endoscopists to help them acquire the ability to manage an unplanned emergency situation during the procedure is also important.

Peer reviewer: Satoru Kakizaki, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine and Molecular Science, Gunma University, Graduate School of Medicine, 3-39-15 Showa-machi, Maebashi, Gunma 371-8511, Japan

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Cho JY, Cho WY. The current status of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;37:317-320 (Korean). |

| 2. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim JJ, Lee JH, Jung HY, Lee GH, Cho JY, Ryu CB, Chun HJ, Park JJ, Lee WS, Kim HS. EMR for early gastric cancer in Korea: a multicenter retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Omata M. Is it possible to predict the procedural time of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:379-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Honda T, Yamamoto H, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Sunada K, Hanatsuka K, Sugano K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial duodenal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |