INTRODUCTION

The treatment of anal fistula has challenged physicians and healers for millennia. References to fistulous disease and use of both fistulotomy and setons can be found in the writings of Hippocrates, dating from 400 BC[1]. This disease process has also been mentioned in non-scientific writings through the years. The great English author and playwright William Shakespeare used what many believe to be a historical fact, that the French King, Charles V, battled with fistula-in-ano, as a comedic plot for his play “All’s well that ends well”[2]. Two thousand years have passed since Hippocrates’ writings and the science of medicine has taken enormous leaps, yet we continue to struggle with fistula-in-ano.

The etymology of the word fistula comes directly from its Latin counterpart which means “pipe”. In medical terminology, a fistula translates to an abnormal connection between a set of organs or vessels that do not normally connect e.g. the connection between the distal alimentary tract and the integument. For years, it has been accepted that the abnormal communication of the lower gastrointestinal system with the perianal region is due to a cryptoglandular infection. It is believed that the anal crypts become blocked by inspissated debris or stool. As a result, an infection develops at the anal glands, which extends in a path of least resistance, forming an abscess in the intersphincteric space leading to the development of a fistula in about one third of patients[3]. However, this explanation does not take into account fistulas caused by Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and actinomycosis, first reported by Swinton in 1964[4]. This duality of cryptoglandular vs non-cryptoglandular fistula is also distinguished in differing treatment strategies. For instance, in actinomycosis, effective treatment mandates surgical therapy with the addition of organism-specific antibiotic therapy. Also, with the recent strides seen in Crohn’s fistula treatment with immunotherapy, one begins to question whether we truly understand the pathophysiology of what we conveniently group into “cryptoglandular” fistulas in the classical sense[4,5].

Current demographic data for fistula-in-ano in the United States are difficult to ascertain, as the Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP), since 1979, has recorded only inpatient procedures through its discharge data from the National Inpatient Sample. Data from a 1979 Ambulatory Care Survey of the National Center of Health Statistics listed 24 000 individuals with the diagnosis of fistula-in-ano[6]. This corresponds to the incidence of 8.6 per hundred thousand per year reported by Sainio in 1984 in the city of Helskini[7]. Another similarity seen in these studies is the 2:1 ratio of men to women in both the US and Finland[6,7]. A more current analysis of data from Europe has been performed by Zanotti in 2007, where queries of databases in the UK, Spain, Germany and Italy showed an incidence ranging from 1.04 per 10 000 in Spain to 2.32 per 10 000 in Italy[8]. These numbers are considerably higher than those reported from Finland in the 1980s.

A common theme in this disease process in all its forms is the presence of stool within the wound, both before and after any treatment strategies. Surgeons abhor the thought of stool in surgical wounds, yet in fistula-in-ano we have to accept the fact that a fresh surgical wound will be bathed in feces on a daily basis. In Crohn’s fistulous disease, it has been shown that proximal diversion helps decrease activity of disease and degree of sepsis. Interestingly, this finding is independent of the severity of Crohn’s-related rectal inflammation, and thus is believed to be directly related to the diversion of stool[9]. Nevertheless, proximal diversion for what we classify as routine “cryptoglandular” fistulous disease would be considered excessive to both patients and providers. Surgeons promote cleanliness with vigilant wound care and sitz baths; however, the fact remains that from simple fistulotomy to the most sophisticated repair, we accept that patients’ wounds will encounter stool, mucus, and purulence on a daily basis.

The goals of the treatment of fistula-in-ano include resolving the acute-on-chronic inflammatory process, maintaining continence, and preventing future recurrence. In reality, treatment-related incontinence, either to gas, stool or both, is the most important consideration of effective eradication of disease. Continence-related morbidity has plagued physicians through history, a fact that is evidenced even in antiquity, by the use of horse hair setons described by Hippocrates in his writings[1].

For years surgeons have performed a straightforward and effective treatment for fistula-in-ano. Simple fistulotomy, i.e. the complete laying open of the tract between the external secondary opening and the internal primary opening has resulted in success rates in the 95% range[10]. Marsupialization of the tract with a locking absorbable suture (as opposed to allowing healing by secondary intention) has been shown to decrease healing time by reducing the size of the open wound[11]. At first glance, fistulotomy should prove to be the ideal treatment method, especially when compared to the much less desirable success rates seen for treatments of other fistulous diseases such as rectovaginal or enterocutaneous fistulas. However, anorectal fistula may present in a variety of forms, and fistulotomy alone can only be used safely for “simple” disease, comprising of intersphincteric fistulas, which represent about 45% of all fistulas[12]. Similarly, if a fistula is transsphincteric but superficial in nature, and not in the anterior hemisphere in women, one may opt to perform fistulotomy with relative safety. It is important to remember, however, that fistulotomy, even for what is classified as “simple” fistula, will result in some form of incontinence in about 12% of patients[13]. The existence of complex fistulas, or those where a fistulotomy would result in incontinence, comprise approximately 50% of this disease process. These complex fistulas include high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, extrasphincteric, all anterior transsphincteric fistulas in women and those caused by Crohn’s disease and secondary to coloanal anastomosis[14].

The aim of surgical therapy of fistula is cure. If one is too aggressive with fistulotomy, cure may be achieved at a cost of incontinence. On the other hand, being too conservative, while striving to maintain continence, will result in recurrence or persistence of the fistula.

SETONS

The utilization of cutting setons, whose origins can be traced to the writings of Hippocrates, attempts to address the issue of incontinence with the performance of a fistulotomy in “complex” fistulas. In theory, it is believed that sequential tightening of a seton, over the course of weeks, will produce fibrosis and avoidance of a major sphincter defect, thus effectively allowing preservation of external sphincter function. Vial et al[15] performed a systematic review of 18 studies, with over 440 patients. They ascertained a recurrence rate of 5.0% for patients where the internal sphincter was not divided at the time of initial surgery, and 3.0% in instances where the internal sphincter was divided. They noted an overall fecal incontinence rate of 5.6% and 25.2%, with the latter number representing the group with intraoperative internal sphincter division. However, others have suggested an overall incontinence rate of up to 67% with the use of this technique[16]. Furthermore, the use of cutting seton for complex disease creates the problem of substantial patient morbidity with severe patient discomfort associated with incremental tightening of the seton.

Others have described attempts in converting high or complex fistulas into processes amenable to fistulotomy. The placement of a draining seton, with the hopes of converting the tract into more superficial processes, or by developing fibrosis within the transsphincteric tract, have been cited as continence-preserving options in “complex” fistulas. The use of draining setons has also been attempted as a bridging therapy in two-stage sphincter-preserving procedures, in order to allow sufficient time for the subsiding of the inflammatory or infectious process, while better defining the epithelial tract of the fistula. This then allows the utilization of one of many relatively recently defined options for sphincter-preserving treatments of fistula-in-ano. Two-stage procedures, with return to the operating room for fistulotomy, have led, however, to subsequent overall incontinence in 66% of patients[16].

FIBRIN SEALANTS AND BIOPROSTHETIC PLUGS

The injection of fibrin sealants and the more recent use of collagen plugs were initially approached with fervor. In theory, the benefits of the avoidance of post-procedure incontinence, due to the lack of sphincterotomy with the use of either modality, were enticing. Furthermore, both procedures are well tolerated by patients due to minimal dissection. It is important to note that salvage treatment is possible and that the use of either technique does not preclude subsequent treatment with other modalities, and thus does not “burn a bridge” to effective treatment of complex fistulas.

FIBRIN SEALANTS

The use of fibrin sealant was initially seen as a promising treatment strategy due to its relative ease of application, and minimal post-procedure discomfort. Its application usually follows the placement of a draining, non-cutting seton. Although authors such as Tyler et al[17] have reported up to 62% success rates following application, with 57% resolution at re-application for patients who failed initial treatment, other reports such as those by Loungnarath et al[14], with reported 69% overall fistula recurrence, have caused the modality to fall out of favor. Furthermore, Ellis et al[18] reported nearly double the percentage of recurrence of fistulas associated with the use of fibrin glue in combination with advancement flap repair of complex fistulas, when compared to flap alone, in a randomized controlled trial.

ANAL FISTULA PLUGS

Most of the studies on bioprosthetic plugs focus on plugs made of treated porcine submucosa; however, newer synthetic plugs have recently come onto the market. A consensus conference for use of the Surgisis plug was held in Chicago in 2007 to address the discrepancy of trials regarding the efficacy of the plug. It was concluded at the meeting that trans-sphincteric fistulas would be ideal candidates for this method of treatment. However, the plug could be used if deemed appropriate in settings of intersphincteric and extrasphincteric fistulas. Absolute contraindications to the use of bioprosthetic plugs included active infectious disease or abscess, simple fistulas, allergy to pork products, and pouch-vaginal and recto-vaginal fistulas, due to the presence of short tracts. The operative procedure entails accurate identification of the external and internal openings and drainage of any active inflammatory disease or abscess with use of a seton. Once all inflammatory disease is resolved in 6 to 8 wk, the plug is placed after debridement of the internal opening. The plug is drawn snug at the internal opening and sutured in place, and then cut flush at the external opening without fixation at this location[19]. Initial studies after the consensus statement showed success rates from 62% to 83%[20,21]. Most recently, however, McGee et al[22] showed a 43% success rate at a mean follow-up of 25 mo, and noted a three-fold likelihood of resolution of disease with tracts greater than 4 cm.

FLAP PROCEDURES

The relatively more recent use of endoanal rectal advancement flaps, and subsequently perianal dermal-island anoplasty, has shown some promise. The short term success rate of endoanal advancement flaps in complex fistulas has been seen in some studies to be as high as 82%[23]. Similarly a 77% success rate has been shown with the use of a dermal-island anoplasty in complex transsphincteric fistula[24].

Endoanal advancement flaps were first described in 1902 by Noble et al[25] for dealing with rectovaginal fistulas following childbirth. Elting et al[26] first reported the use of this technique for use in fistula-in-ano in 1912. However, its usage in complicated anal fistulous disease became better known in 1985, after Aguilar et al[27] published their results in 189 patients, with 3 recurrences and approximately 7% incidence of incontinence to flatus and no reports of incontinence to stool. The surgical technique, as described by Aguilar, includes complete subcutaneous excision of the external opening, along with all other secondary openings, to the external sphincter muscle margin. Subsequently, a flap originating from the intersphincteric groove is raised and includes anoderm, mucosa and submucosa. The flap should extend 3 to 4 cm proximal from the internal opening, and be trapezoidal in nature, with the base wider than the apex to allow adequate blood supply. The internal opening is excised, and the internal sphincter is closed using absorbable sutures. The flap is then sutured, without tension, to the intersphincteric groove[28]. A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies by Soltani et al[29], including over 1600 patients, showed a success rate of over 80% for fistulas of cryptoglandular origin, with a 13% incidence of some form of incontinence. Further derivatives of this technique have been described, in combination with the use of bioprosthetic plugs or fibrin glue, with mixed results. The endoanal advancement flap, although not always ideal, has become a promising tool. However, its major limitation is that it frequently results in a mucosal ectropion, which produces mucus and gives patients the false sensation of incontinence due to spontaneous discharge and soiling.

Dermal island-flap anoplasty was first described by Del Pino et al[30] in 1996, as an alternative to rectal advancement flaps, in order to reduce risk of mucosal ectropion and anal discharge. The operative technique entails the formation of a tear drop-shaped incision encompassing the perianal skin containing the external opening. The incision is extended just proximal to the internal opening of the trans-sphincteric fistula. Subsequently, the internal opening is excised and debrided, and the internal sphincter at this level is closed using absorbable suture. The flap is mobilized without undermining, and the dermal island is sewn to the rectal mucosa with absorbable sutures. The external opening is neither excised nor debrided. Nelson et al[6] found a procedure failure rate of 23% with an associated patient failure rate of 20% with this method, in a mean follow-up period of 28.4 mo. As of recent publications, incontinence data is not available; however, it is safe to assume it to be similar to that of endoanal rectal advancement flaps.

LIGATION OF INTERSPHINCTERIC FISTULA TRACT

Most recently, the introduction of the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure has sparked interest with good short term results. This procedure, first proposed by Rojansakul in 2007, focuses on the ligation of the intersphincteric tract of the fistula, and can be applicable for both complex and recurrent fistula[31]. In recurrent fistula, previous internal sphincterotomy will impede proper dissection of the tract. This method delineates the trans-sphincteric tract, with careful dissection in the intersphincteric groove, with or without the help of a fistulotomy probe. Once the fistula track is isolated it is ligated with absorbable suture on both proximal and distal sides and divided between the ligatures. The success of LIFT procedure is reported to be 75%-80%[32-34].

TREATMENT STRATEGY

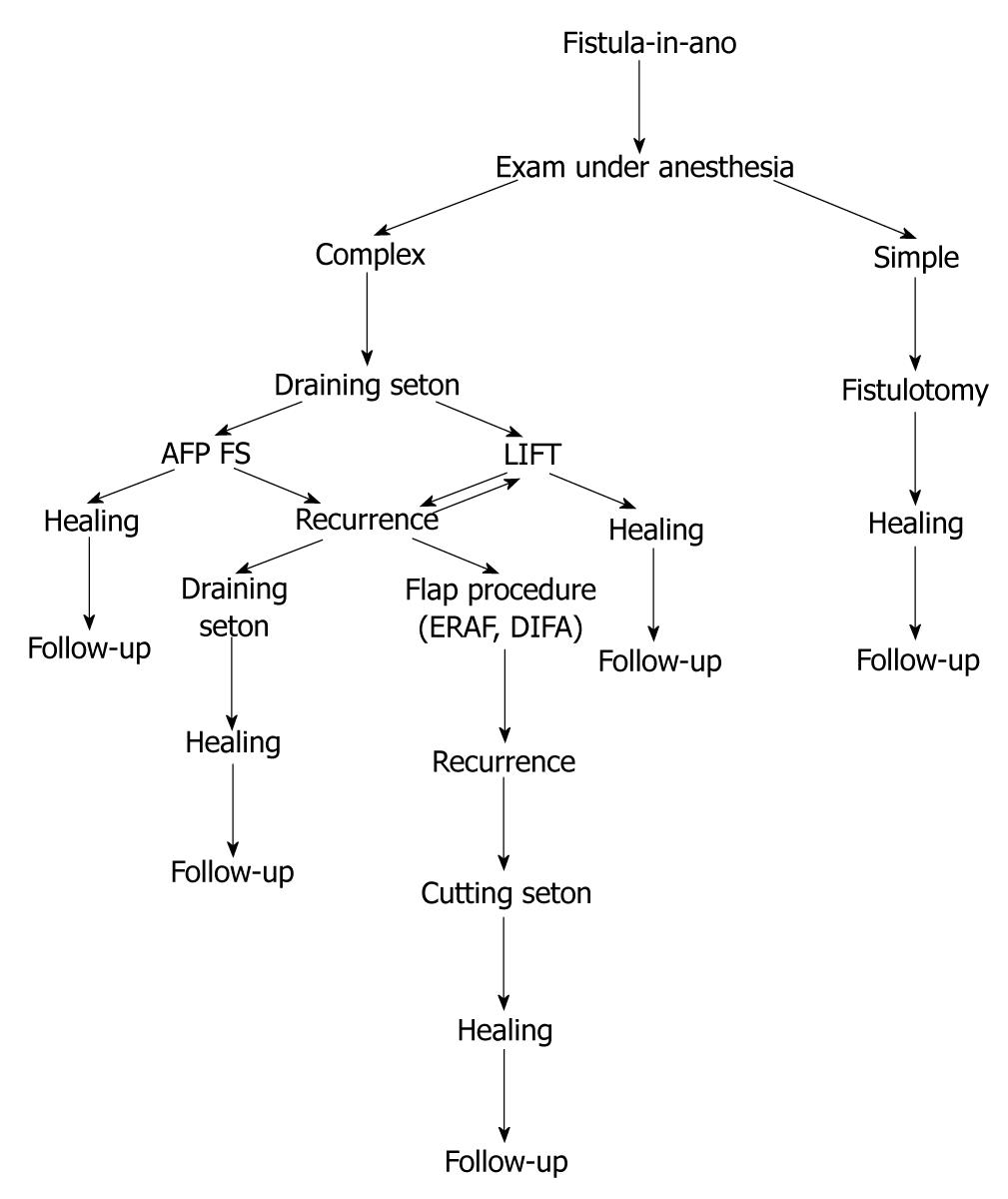

In our experience, simple fistulotomy is attempted if none or minimal amount of external sphincter is involved in the fistulous tract. In all other cases, a draining seton is placed as a bridging therapy for a minimum of six to eight weeks. After this time, a controlled exam under anesthesia is performed, and if the acute inflammatory process is resolved, then our treatment algorithm follows that of conservative management for continence preservation. If at this point minimal sphincter involvement is identified, then simple fistulotomy with marsupialization is performed. If the tract is deemed “complex” in nature, then a flap, either dermal-island or endoanal advancement, is used, with adequate drainage of the tract through the external opening using a small caliber Malecot drain. If the tract appears to be of sufficient length, then use of bioprosthetic plug is considered. Currently we are studying the utility and efficacy of the LIFT procedure; however, early results seem promising in nature (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Treatment algorithm.

AFP: Anal fistula plug; FS: Fibrin sealant; ERAF: Endoanal advancemnt flap; DIFA: Dermal island flap anoplasty; LIFT: Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract.

Fistula-in-ano continues to prove a formidable challenge to surgeons. Our understanding of the disease process, although well established, contains gaps in the understanding of complex pathophysiology. While effective treatment has been established for “simple” cases, the concern for iatrogenic sphincter injuries, with resulting incontinence, continues to plague cases of “complex” disease with major sphincter involvement. Recent strides in the development of sophisticated procedures for continence preservation appear to be promising. However, due to location of fistula, contamination of all repairs with feculent soilage challenges the integrity our results. Concern for incontinence has resulted in trading a single-stage curative procedure (fistulotomy) for multiple sphincter-preserving operations, each with varying success rates.

Peer reviewers: Julio Mayol, MD, PhD, Department of Digestive Surgery, Hospital Clinico San Carlos, MARTIN-LAGOS S/n, Madrid, 28040, Spain; Paola De Nardi, MD, Department of Surgery, Scientific Institute San Raffaele Hospital, Via Olgettina 60, Milan, 20132, Italy; Sharad Karandikar, Mr, Consultant General and Colorectal Surgeon, Department of General Surgery, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, B95SS, United Kingdom

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH