Published online Jul 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3263

Revised: March 1, 2011

Accepted: March 8, 2011

Published online: July 21, 2011

We report a rare case of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from sigmoid colon cancer, which was accompanied by peritoneal dissemination. A 58-year-old female patient presented with massive right pleural effusion, ascites and a huge pelvic mass. Under the diagnosis of an advanced ovarian tumor, bilateral oophorectomy was performed and sigmoidectomy was also carried out after intraoperative diagnosis of peritoneal dissemination involving the sigmoid colon. However, immunohistochemical staining revealed that the ovarian lesions were metastasis from the primary advanced colon cancer. Postoperatively, ascites and pleural effusion subsided, and the diagnosis of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to a metastatic ovarian tumor from colon cancer was determined. The patient is now undergoing a regimen of chemotherapy for colon cancer without recurrence of ascites or hydrothorax 10 mo after the surgery. Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to a metastatic ovarian tumor from colon cancer is rare but clinically important because long-term alleviation of symptoms can be achieved by surgical resection. This case report suggests that selected patients, even with peritoneal dissemination, may obtain palliation from surgical resection of metastatic ovarian tumors.

- Citation: Maeda H, Okabayashi T, Hanazaki K, Kobayashi M. Clinical experience of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(27): 3263-3266

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i27/3263.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3263

Meigs’ Syndrome is characterized by pleural effusion and ascites associated with ovarian fibroma or fibroma-like tumors, which are relieved by resection of the responsible lesions. When associated with other types of ovarian tumor, the condition is termed Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome[1,2]. Malignancy from the gastrointestinal tract, including colon cancer, is a rare etiology for this syndrome and only a few cases have been reported[3-7]. This case report documents our clinical experience, reviews previously reported cases and discusses the diagnosis and treatment of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from colorectal cancer.

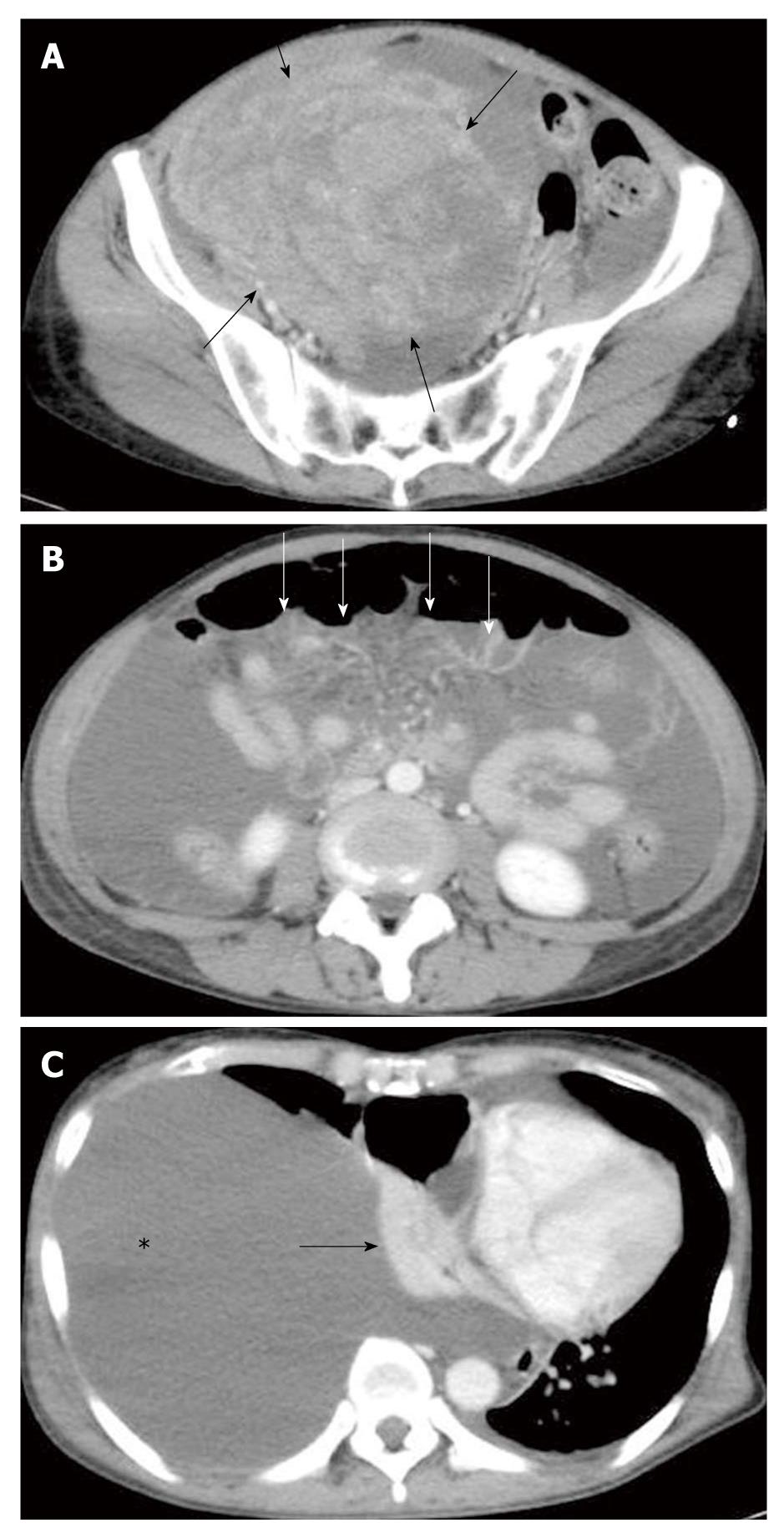

A 58-year-old female presented to the hospital with a 1-mo history of general fatigue, dyspnea, abdominal distention, loss of appetite and decreased urine volume, which had worsened progressively over the previous few days. Her past medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination found a large mass in her lower abdomen. The peripheral blood test showed elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 63.8 ng/mL (normal, < 5 ng/mL), and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 125: 921 U/mL (normal, < 45 U/mL) and a normal level of CA19-9: 2 U/mL (normal, < 37 U/mL). Enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated fluid retention and a round mass with a maximum diameter of 15 cm in the pelvic cavity (Figure 1A). Peritoneal dissemination was highly suspected (Figure 1B), and further examination of the ascites was not performed. The massive right pleural effusion occupied the pleural cavity causing atelectasis and compression of the mediastinum to the left side (Figure 1C). Intermittent drainage of pleural effusion was performed to alleviate severe dyspnea, yielding 4000 mL of serous fluid without malignant cells on cytological examination over 3 d. The patient’s poor general condition and refusal prevented us from further examination including routine gastrointestinal endoscopy, and advanced ovarian cancer was tentatively diagnosed. Subsequent palliative surgery disclosed an enlarged right ovarian tumor and sparsely distributed peritoneal dissemination with mid-sigmoid colon involvement. In addition to bilateral oophorectomy, sigmoidectomy and primary anastomosis were carried out in case of colonic obstruction.

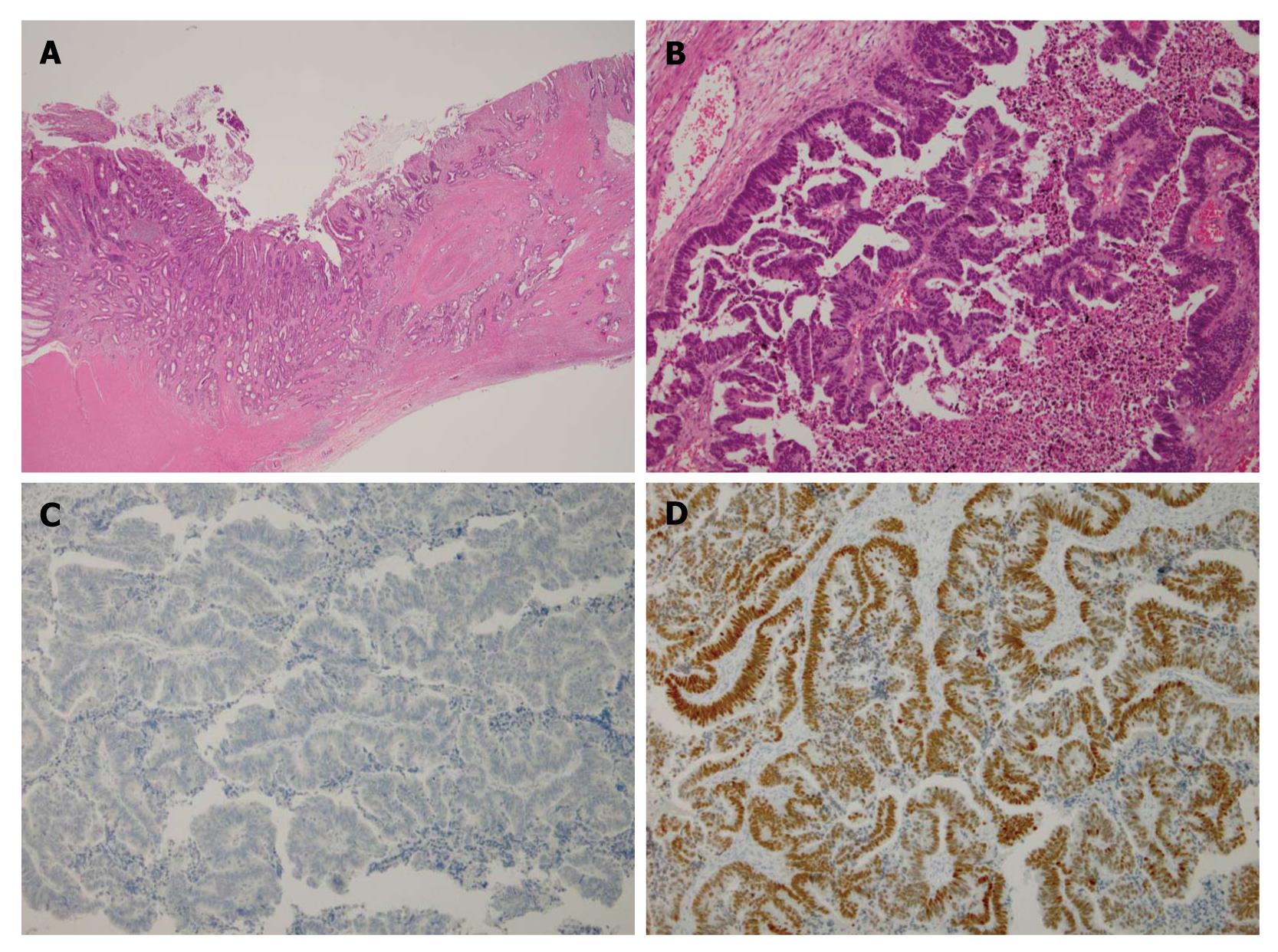

Histopathological examination of resected specimens showed that both the ovarian and colonic lesions were composed of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 2A and B). The dissected paracolic nodes showed positive malignant cells. However, immunohistochemical staining of cytokeratin 7, mucin-5AC and CA125 was negative and that of cytokeratin 20, CEA and CDX-2 was positive (Figure 2C and D), confirming the ovarian tumors were metastases from primary colon cancer[8]. The postoperative course was uneventful and ascites and pleural effusion subsided. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), leucovorin and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) were administered every 2 wk for 5 mo and then changed to 5-FU, leucovorin and irinotecan (FOLFILI) due to neuropathy. Ten months after the surgery, tumor markers were within the normal range and abdominal CT showed no sign of tumor growth or recurrent fluid retention either in the pleural or abdominal cavity. She did not experience a marked change in bowel habit after the surgery and during chemotherapy. The diagnosis of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to metastatic ovarian tumor from colon cancer was determined.

Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from colon cancer is a rare condition. In 2000, Nagakura et al[3] reviewed 5 cases including 3 Japanese cases. Thereafter only 4 subsequent reports of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome with the same etiology were reported (Table 1). The age of the patients was relatively low considering that the mean age of occurrence of colorectal cancer is approximately 64-71 years[9,10]. Pleural effusion is more prevalent in the right side, and the ovarian tumor is usually large (mean diameter 16 cm) and predominantly bilateral.

| Reference | Age (yr) | Onset of syndrome | Site of pleural effusion | Synchronous metastasis | Diameter of ovarian tumor (cm) | Site of ovarian tumor | Long-term outcome |

| Nagakura et al[3] | 35 | Metachronous | Right | None | 15 | Unilateral | 108 mo, alive |

| Nagakura et al[3] | 40 | Synchronous | Right | None | Not given | Bilateral | 1.5 mo, alive |

| Nagakura et al[3] | 39 | Synchronous | Bilateral | None | 24 | Unilateral | 12 mo, alive |

| Nagakura et al[3] | 75 | Synchronous | Right | Peritoneum | 21 | Unilateral | Not given |

| Nagakura et al[3] | 53 | Synchronous | Right | None | 18 | Bilateral | 52 mo, alive |

| Feldman et al[4] | 49 | Metachronous | Left | None | 13 | Right | 6 mo, alive |

| Ohsawa et al[5] | 41 | Synchronous | Bilateral | Peritoneum | 16 | Bilateral | 10 mo, died |

| Rubinstein et al[6] | 61 | Synchronous | Bilateral | None | 13 | Bilateral | Not given |

| Okuchi et al[7] | 42 | Synchronous | Right | Liver, lung | 11.5 | Left | 12 mo, died |

| Present case | 58 | Synchronous | Right | Peritoneum | 15 | Bilateral | 10 mo, alive |

The diagnosis of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome is difficult because of its rarity and the similarity of the symptoms and signs to those of terminal malignant disease. Negative cytological results of ascites and pleural effusion might be informative for differentiating between Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome and advanced cancer. Ascites due to peritoneal dissemination or peritonitis carcinomatosa is generally refractory to surgical or medical treatment, rendering surgical intervention for patients with this condition mostly harmful. Nevertheless, a negative result of cytology or peritoneal dissemination is not necessarily a requirement for the diagnosis of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome. Three out of 10 reported cases of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to metastatic colorectal cancer had peritoneal dissemination (Table 1).

Recently, an elevated level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in blood and ascites were reported in a patient with Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to colon cancer[7]. In that case, the hypersecretion of VEGF from oviducts was considered to play a key role in the pathogenesis of ascites and pleural effusion[7]. VEGF levels in blood and ascites might be useful for determining which patients would recover from massive fluid retention by surgical resection of metastatic ovarian tumors, even with a positive cytological result of ascites.

In the cases reviewed, the postoperative course was uneventful, symptoms were rapidly relieved, and palliation of the symptoms was long lasting[3-7]. A study from a single institute in Japan reported that the 3-year survival-rate of 5 cases of pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome was 37.5%[11]. However, surgeons should be prudent in the use of surgery. In general, colon cancer with ovarian metastasis is hard to cure[12]. Colon cancer with ascites is associated with frequent postoperative complications[13]. In addition, publication bias must be considered when interpreting rare conditions. Without obvious evidence, a regional lymphadenectomy should be reserved for selected patients, and oophorectomy with colorectal resection with minimal invasion should be the first choice surgical strategy.

In conclusion, ovarian metastasis from sigmoid colon cancer is a potential cause of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome. Surgical resection can be the treatment of choice for a selected patient even with the apparent peritoneal dissemination, because it can provide long-term palliation.

Peer reviewers: Alessandro Fichera, MD, FACS, FASCRS, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5031, Chicago, IL 60637, United States; Lin Zhang, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, UPCI Research Pavilion, Room 2.42d, Hillman Cancer Center, 5117 Centre Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1863, United States; Luis Bujanda, PhD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, CIBEREHD, University of the Basque Country, Donostia Hospital, Paseo Dr. Beguiristain s/n, 20014 San Sebastián, Spain

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Meigs JV. Pelvic tumors other than fibromas of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax. Obstet Gynecol. 1954;3:471-486. |

| 2. | Meigs JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs' syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;67:962-985. |

| 3. | Nagakura S, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome caused by secondary ovarian tumors from gastrointestinal cancer. A case report and review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2000;17:418-419. |

| 4. | Feldman ED, Hughes MS, Stratton P, Schrump DS, Alexander HR Jr. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome secondary to isolated colorectal metastasis to ovary: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:248-251. |

| 5. | Ohsawa T, Ishida H, Nakada H, Inokuma S, Hashimoto D, Kuroda H, Itoyama S. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from colon cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:387-391. |

| 6. | Rubinstein Y, Dashkovsky I, Cozacov C, Hadary A, Zidan J. Pseudo meigs' syndrome secondary to colorectal adenocarcinoma metastasis to the ovaries. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1334-1336. |

| 7. | Okuchi Y, Nagayama S, Mori Y, Kawamura J, Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Yoshizawa A, Sakai Y. VEGF hypersecretion as a plausible mechanism for pseudo-meigs' syndrome in advanced colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:476-481. |

| 8. | Shin JH, Bae JH, Lee A, Jung CK, Yim HW, Park JS, Lee KY. CK7, CK20, CDX2 and MUC2 Immunohistochemical staining used to distinguish metastatic colorectal carcinoma involving ovary from primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:208-213. |

| 9. | Endreseth BH, Romundstad P, Myrvold HE, Bjerkeset T, Wibe A. Rectal cancer treatment of the elderly. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:471-479. |

| 10. | Kotake K, Honjo S, Sugihara K, Kato T, Kodaira S, Takahashi T, Yasutomi M, Muto T, Koyama Y. Changes in colorectal cancer during a 20-year period: an extended report from the multi-institutional registry of large bowel cancer, Japan. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:S32-S43. |

| 11. | Ishii M, Ishibashi K, Sobajima J, Ohsawa T, Okada N, Kumamoto K, Haga N, Yokoyama M, Ishida H. [Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome caused by ovarium metastasis from colorectal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:2591-2593. |

| 12. | Miller BE, Pittman B, Wan JY, Fleming M. Colon cancer with metastasis to the ovary at time of initial diagnosis. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:368-371. |

| 13. | Longo WE, Virgo KS, Johnson FE, Oprian CA, Vernava AM, Wade TP, Phelan MA, Henderson WG, Daley J, Khuri SF. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality after colectomy for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:83-91. |