Published online Apr 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1879

Revised: November 22, 2010

Accepted: November 29, 2010

Published online: April 14, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients from South-East Asia and Australia.

METHODS: In this open-label, phase II study, the main eligibility criteria were epidermal growth factor receptor-positive mCRC with progressive disease within 3 mo of an irinotecan-based regimen as the most recent chemotherapy. Patients received cetuximab 400 mg/m2 initially, then 250 mg/m2 every week, with the same regimen of irinotecan on which the patients had progressed (4 pre-defined regimens allowed). The primary objective was evaluation of progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 wk. Secondary objectives included a further investigation of PFS, and an assessment of the overall response rate (ORR), duration of response, time to treatment failure (TTF), overall survival and the safety profile.

RESULTS: One hundred and twenty nine patients were enrolled from 25 centers in the Asia-Pacific region and of these 123 received cetuximab plus irinotecan. The most common recent irinotecan regimen used was 180 mg/m2 every 2 wk which had been used in 93 patients (75.6%). The PFS rate at 12 wk was 50% (95% confidence interval (CI, 41-59) and median PFS time was 12.1 wk (95% CI: 9.7-17.7). The ORR was 13.8% (95% CI: 8.3-21.2) and disease control rate was 49.6% (95% CI: 40.5-58.8). Median duration of response was 31.1 wk (95% CI: 18.0-42.6) and median overall survival was 9.5 mo (95% CI, 7.5-11.7). The median TTF was 11.7 wk (95% CI: 9.1-17.4). Treatment was generally well tolerated. The most common grade 3/4 adverse events were diarrhea (13.8%), neutropenia (8.9%), rash (5.7%) and vomiting (5.7%).

CONCLUSION: In patients from Asia and Australia, this study confirms the activity and safety of cetuximab plus irinotecan observed in previous studies in Europe and South America.

- Citation: Lim R, Sun Y, Im SA, Hsieh RK, Yau TK, Bonaventura A, Cheirsilpa A, Esser R, Mueser M, Advani S. Cetuximab plus irinotecan in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients: The ELSIE study. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(14): 1879-1888

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i14/1879.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1879

Based on 2002 estimates, there are approximately 1 million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) annually worldwide, with 529 000 deaths from the disease[1]. Approximately 25% of patients with CRC present with metastatic CRC (mCRC), and 25%-30% of newly diagnosed patients with CRC will eventually develop metastatic disease[2]. Five-year survival rates for patients with newly diagnosed mCRC have improved from 9.1% during 1990-1997 to 19.2% for 2001-2003 to a predicted value of 32% for 2004-2006[3]. The observed increase in survival is associated with the adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy regimens[3]. In 2002, the annual incidence and mortality associated with CRC in Eastern and South-East Asia were approximately 307 600 and 160 000 cases, respectively, and in Australia, they were around 12 300 and 4900 cases, respectively[1]. While the incidence and mortality rates for CRC are generally stabilizing in Western and developed countries, those in economically developing countries and in Eastern and South East Asia are increasing[1,4,5].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is frequently expressed in CRC[6-9], where high levels of expression have been reported to be associated with reduced survival time in patients with mCRC[10]. Cetuximab (Erbitux® developed by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany) under license from ImClone Systems, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly, Branchburg, NJ, USA) is a monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 antibody that specifically targets the EGFR with high affinity, and exerts an inhibitory effect on tumor cell proliferation, survival, motility, invasion and angiogenesis[11]. Cetuximab has been shown to be efficacious and well tolerated in patients failing irinotecan therapy either in combination with irinotecan or as monotherapy[7], and in combination with irinotecan in patients failing first-line oxaliplatin-based therapy[12]. In the pivotal registration study (BOND) for cetuximab conducted in European mCRC patients failing irinotecan-based therapy, cetuximab plus irinotecan was well tolerated and was associated with a disease control rate of 56%, a median time to progression of 4.1 mo and median overall survival of 8.6 mo[7]. The NCIC-CO.17 trial demonstrated that cetuximab monotherapy significantly improved response rate, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival time in heavily pre-treated patients with mCRC with KRAS wild-type tumors compared with patients receiving best supportive care alone[13]. Findings from the BOND study have been confirmed in a community practice setting in the large Monoclonal Antibody Erbitux in a European Pre-License Study (MABEL)[14]. This study investigated the combination of different irinotecan regimens with cetuximab in 1147 patients with mCRC progressing on irinotecan. To date the MABEL study is the largest published cetuximab study in this setting, reporting a PFS rate at 12 wk of 61% and an estimated median survival time of 9.2 mo[14]. Data from the Latin American Erbitux Pre-License Study (LABEL) in Latin American patients with EGFR-expressing mCRC progressing on irinotecan suggest cetuximab to be active and tolerable, with a safety profile similar to that described in European patients[15].

At the time of the design of this study there were no standard treatment options available for patients in this setting. Approval following the BOND trial, for cetuximab in combination with irinotecan for mCRC patients in this setting therefore provided the rationale for this study. Thus the phase II Erbitux® pre-License Study In the East (ELSIE) was designed to investigate the combination of irinotecan-containing regimens with cetuximab in irinotecan-refractory patients with mCRC from Asia and Australia.

All patients provided written informed consent. Main inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥ 80, histologically confirmed diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum, metastatic disease not suitable for curative treatment, immunohistochemical evidence of EGFR expression in the primary tumor or metastasis, previous treatment with 1 of 4 pre-defined irinotecan regimens for ≥ 6 wk as the most recent chemotherapy, disease progression on or within 3 mo of the most recent irinotecan regimen, able to tolerate irinotecan continuation, no more than 3 previous lines of chemotherapy, and adequate hepatic, renal and bone marrow function. Main exclusion criteria were known or suspected brain metastases, radiotherapy or major surgery within the 4 wk prior to study entry, previous EGFR-targeted therapy, coronary heart disease or history of myocardial infarction or uncontrolled arrhythmia, other malignancy within 5 years (except basal cell carcinoma of the skin or pre-invasive carcinoma of the cervix), and pregnancy.

This was an open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter, phase II study carried out in 25 centers in 8 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Patients initially received an infusion of cetuximab 400 mg/m2 over 2 h followed by weekly infusions of 250 mg/m2 over 1 h in addition to irinotecan treatment at the same dosage regimen (including previous dose reductions) on which the subject had become refractory to irinotecan. Irinotecan was administered intravenously over 30-90 min with at least 1 h between the end of cetuximab and the start of infusion of irinotecan. The irinotecan regimens allowed as pre-study treatment and continued during the study were 100 or 125 mg/m2 weekly for 4 wk then 2 wk rest (1 cycle); 100 or 125 mg/m2 weekly for 2 consecutive wk out of 3 (1 cycle); 180 or 210 mg/m2 every 2 wk (1 cycle); and 300 or 350 mg/m2 every 3 wk (1 cycle). The first 3 pre-study irinotecan regimes could have been administered either as single-agent irinotecan or in combination; however, only single-agent irinotecan was accepted for the fourth regimen. Study treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. In case of an irinotecan-related toxicity, irinotecan could be stopped and treatment could be continued with cetuximab monotherapy. Two irinotecan dose reductions were allowed for toxicity prior to study entry and during the study for all regimens except for patients receiving 100 mg/m2 weekly where only 1 dose reduction was allowed.

The primary objective was the assessment of PFS rate after 12 wk of treatment. Secondary objectives included further evaluation of PFS, and the assessment of best overall confirmed response rate, duration of response, time to treatment failure (TTF), overall survival time, safety and toxicity.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as well as the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP, 1996).

Pre-screening of patients was performed within 3 mo after confirmation of disease progression on irinotecan-based chemotherapy and included informed consent, collection of demographic data, tumor diagnosis and the determination of tumor EGFR expression which was performed by designated pathology laboratories in Hong Kong, India and China by immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue slides using a standardized protocol with the DAKO EGFR pharmDX kit (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Baseline evaluations were performed within 21 d prior to the start of study treatment; pre-study staging by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed within 28 d. After the start of treatment, imaging (CT or MRI) was performed every 6 wk. Based on these images, the tumor response was assessed according to modified World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria every 6 wk during study treatment. Follow-up for survival occurred every 12 wk from the end of the study visit and included recording of subsequent treatments.

Adverse events (AEs) were reported weekly at each infusion visit, at the time of disease progression or study discontinuation, and up to 6 wk after the last infusion of study treatment. AEs were reported by severity according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) version 2 using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 10 preferred terms as event category and MedDRA body system/primary system organ class (SOC) as SOC category.

Safety and efficacy analyses were carried out considering the intention-to-treat (ITT)/safety population, which comprised all patients who had received any dose of study treatment. As patients were not randomized to treatment and the number of patients per individual treatment regimen was expected to be small, all data were analyzed independently of the on-study irinotecan regimen. The primary objective of this study was to determine the PFS rate at 12 wk after initiation of cetuximab treatment. Time-to-event analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier estimates. Confidence intervals (CIs) for the median were calculated according to Brookmeyer and Crowley[16]. CIs for the event-free rate estimates, including the primary variable, were derived from the Kaplan-Meier curve at defined time points. The estimate of the standard error was computed using Greenwood’s formula[17]. PFS was defined as the time from the first study medication to the first observation of radiologically confirmed disease progression, symptomatic deterioration leading to discontinuation of study treatment (unless imaging confirmed absence of progressive disease), or death due to any cause within 60 d of the last on-study tumor assessment. The best overall confirmed response was defined as the best confirmed response from start of treatment until disease progression. Duration of response in patients with a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) was defined as the time from first assessment of CR/PR to the first time disease progression was documented or death within the trial or until death within 60 d after last tumor assessment, whichever occurred first. The time to TTF was defined as the time from the start of the first cetuximab treatment until the date of the first occurrence of an event defining treatment failure, i.e. withdrawal of any study treatment due to AEs or progressive disease or withdrawal of consent or death, whichever occurred first. The overall survival time was defined as the time from the day of first infusion of study medication to death. For subjects who were still alive at the last survival follow-up, or who were lost to follow-up, survival was censored at the last recorded date that the subject was known to be alive.

A subgroup analysis that used a landmark method for the analysis of time-dependent covariates was carried out to examine whether the development and severity of acne-like rash that occurred during the first 21 d of treatment was associated with prolonged survival time. To avoid selection bias as a consequence of the early exclusion of patients, this analysis was limited to all patients in the ITT/safety population who were still under on-study treatment at day 21. Consequently, overall survival time was analyzed for this subgroup by using the landmark of study day 22 (and not day 1) as the start day. Survival was further analyzed in other subgroups based on known prognostic variables.

To ensure adequate precision of estimates, the sample size determination was based on a confidence limit approach. The expected rate of progression-free patients 12 wk after start of study treatment was 50%. It was calculated that with the enrollment of 150 patients, the observed 95% CI for this point estimate would have a range of approximately ± 8%.

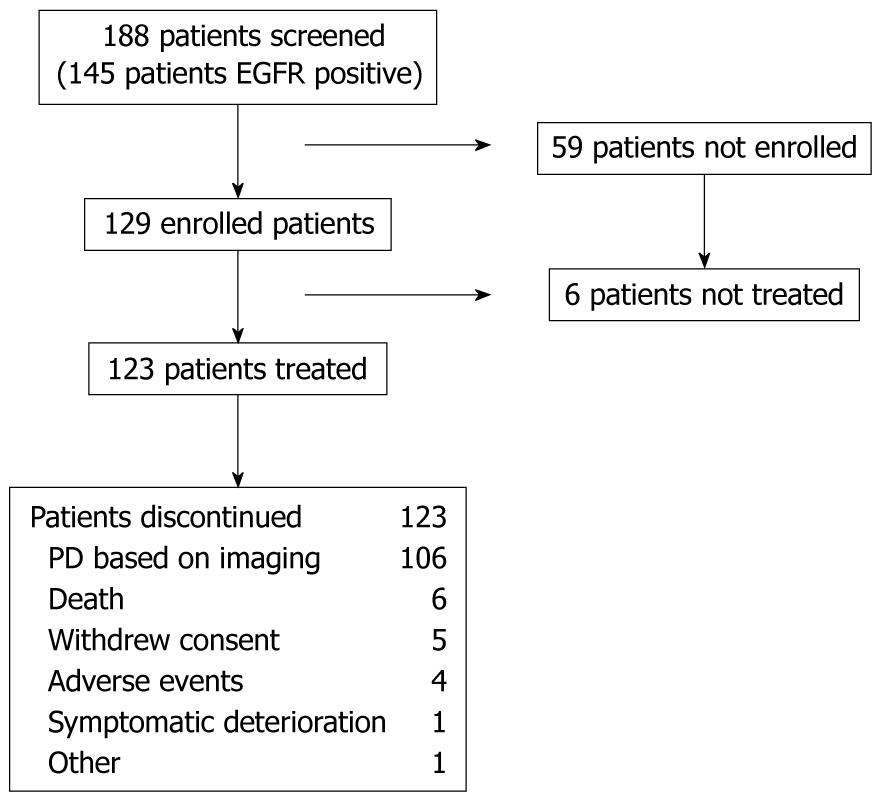

Patient characteristics are summarized in Figure 1. Between November 2005 and September 2006, 188 patients were screened at 25 centers in Australia (3 centers), China (6), Hong Kong (2), India (3) Korea (5), Singapore (1), Taiwan (3), and Thailand (2). Of these patients, 145 (77%) had EGFR detected in their tumor sample (data were missing for 4 patients), 129 patients were enrolled and of these, 123 patients were treated and formed the ITT/safety population. The main reason for study discontinuation was disease progression (86.2%). There were 6 patients who were treated until death (5 of these deaths due to disease progression, 1 due to chemotherapy-related AEs, 4 patients stopped treatment due to AEs and 5 patients withdrew consent.

Patient and disease characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (59.3%), the median age was 56 years (range, 24-78 years) and 74.8% of patients were aged < 65 years. The most common primary tumor site was the colon (57.7%), and 74.8% of patients had liver metastases, 56.1% had lung metastases and more than 30% of patients had other organs involved. The median duration of mCRC at baseline was 8.8 mo (range, 1-56).

| Characteristic | Patients(n = 123) |

| Patient characteristics | |

| Median age, yr (range) | 56 (24-78) |

| Age categories, n (%) | |

| < 65 yr | 92 (74.8) |

| ≥ 65-75 yr | 28 (22.8) |

| ≥ 75 yr | 3 (2.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 73 (59.3) |

| Female | 50 (40.7) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 9 (7.3) |

| Asian (Chinese) | 66 (53.7) |

| Asian (non Chinese) | 48 (39.0) |

| Karnofsky performance status, n (%) | |

| 80 | 39 (31.7) |

| 90 | 52 (42.3) |

| 100 | 32 (26.0) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| Median duration of CRC, mo (range) | 15.7 (2-78) |

| Median duration of mCRC, mo (range) | 8.8 (1-56) |

| Localization of tumor, n (%) | |

| Colon | 71 (57.7) |

| Rectum | 49 (39.8) |

| Colon and rectum | 3 (2.4) |

| No. of organs with metastasis, n (%) | |

| 1 | 51 (41.5) |

| 2 | 53 (43.1) |

| 3 | 12 (9.8) |

| > 3 | 7 (5.7) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | |

| No. of previous treatment lines (non-adjuvant) | |

| 1 | 66 (53.7) |

| 2 | 37 (30.1) |

| 3 | 20 (16.3) |

| Previous adjuvant chemotherapy | 37 (30.1) |

| Previous non-adjuvant oxaliplatin therapy | 50 (40.7) |

| Most recent irinotecan therapy, n (%) | |

| 100 or 125 mg/m2 weekly for 4 consecutive wk followed by 2 wk of rest | 1 (0.8) |

| 100 or 125 mg/m2 weekly for 2 consecutive wk out of 3 | 15 (12.2) |

| 180 or 210 mg/m2 every 2 wk1 | 94 (76.4) |

| 300 or 350 mg/m2 every 3 wk | 9 (7.3) |

| Other | 4 (3.3) |

| Type of therapy, n (%) | |

| Irinotecan monotherapy | 10 (8.1) |

| Irinotecan + 5-FU or analog | 104 (84.6) |

| Irinotecan + 5-FU or analog + other | 8 (6.5) |

| Irinotecan + other | 4 (3.3) |

| Median duration, wk (Q1-Q3) | 14.3 (7.3-22.4) |

| Best overall response to most recent irinotecan treatment, n (%) | |

| Complete response | 3 (2.4) |

| Partial response | 17 (13.8) |

| Stable disease | 43 (35.0) |

| Progressive disease | 59 (48.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) |

The most common recent irinotecan regimen used was 180 mg/m2 every 2 wk, which had been used in 93 patients. Approximately half of the patients (49.6%) had a time interval of 1-3 mo between the last pre-study dose of irinotecan and the first dose of cetuximab and the interval was < 1 mo in 35% of patients. All other patients had an interval of less than 6 mo between the most recent irinotecan dose and the start of study treatment.

Treatment exposure is summarized in Table 2. At least 50% of patients received cetuximab treatment for ≥ 12 wk and were administered ≥ 12 infusions. The longest treatment duration was 98 wk and almost 5% of patients received more than 50 infusions of cetuximab. Relative dose intensity (RDI) of cetuximab of ≥ 90% was achieved in 89.2% of patients. Furthermore, 118 patients (95.9%) were treated at the planned standard dose of cetuximab. Four patients (3.3%) had at least 1 dose reduction of cetuximab and information was missing for 1 patient. Dose reductions were required at the occurrence of second or third incidences of grade 3 skin toxicity according to the protocol.

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 123) | |

| Cetuximab1 | Irinotecan2 | |

| Duration, wk | ||

| Median | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Q1-Q3 | 6.0-25.0 | 6.0-25.6 |

| Total number of infusions, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 0 | 2 (1.6) |

| 1-5 | 13 (10.6) | 57 (46.3) |

| 6-10 | 42 (34.1) | 35 (28.5) |

| 11-20 | 30 (24.4) | 19 (15.4)2 |

| 21-30 | 20 (16.3) | 6 (4.9) |

| 31-40 | 7 (5.7) | 2 (1.6) |

| 41-50 | 5 (4.1) | 1 (0.8) |

| > 50 | 6 (4.9) | 1 (0.8) |

| Cumulative dose, mg/m2 | ||

| Median | 3143.7 | 894.8 |

| Q1-Q3 | 1650.8-6110.6 | 532.0-1980.4 |

| Cetuximab dose intensity, mg/m2 per week | ||

| Median | 246.7 | |

| Q1-Q3 | 236.0-250.3 | |

| Irinotecan dose intensity, mg/m2 per 6 wk | ||

| Median | 507.8 | |

| Q1-Q3 | 407.6-539.5 | |

| Relative dose intensity, n (%) | ||

| < 60% | 2 (1.7) | 5 (4.3) |

| 60% to 80% | 5 (4.2) | 21 (17.9) |

| 80% to 90% | 6 (5.0) | 15 (12.8) |

| ≥ 90% | 107 (89.2) | 76 (65.0) |

| Patients who stopped irinotecan and received cetuximab, n (%) | 14 (11.4) | |

| Median duration of cetuximab monotherapy after stopping irinotecan, wk (range) | 2.5 (0.9-23.0) | |

| Patients who stopped combination treatment and received irinotecan only, n (%) | 0 | |

The median duration of irinotecan exposure was 12 wk, with patients receiving a median of 6 cycles. RDI of ≥ 90% of irinotecan was achieved in 65% of patients. Approximately three-quarters of patients (74%, n = 91) received ≥ 80% of the planned dose of irinotecan. In total, 74 patients (60.2%) required at least 1 dose reduction of irinotecan, which included pre-study dose reductions.

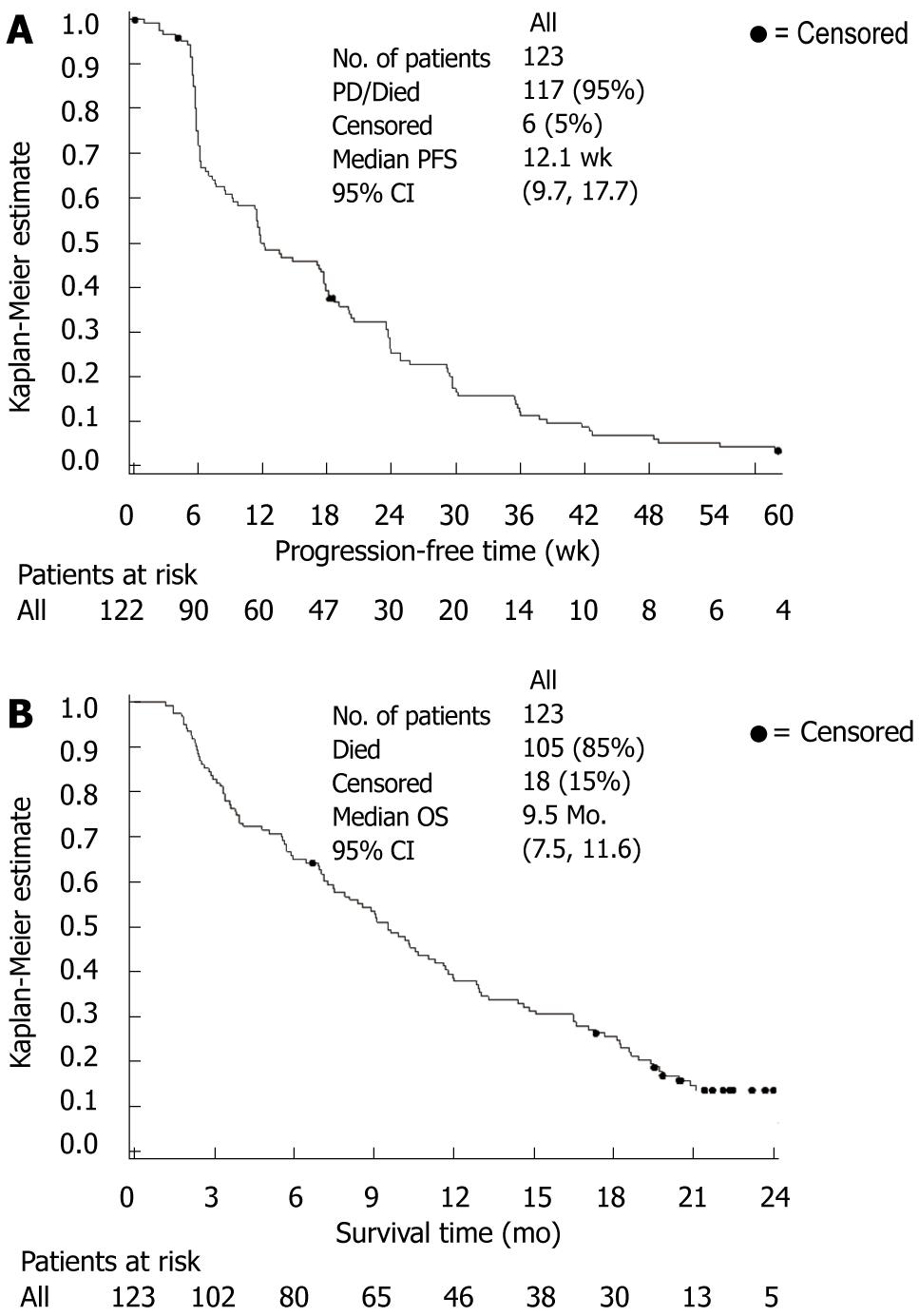

Study results are summarized in Table 3. The 12-wk PFS rate was found to be 50% (95% CI: 41-59). The median PFS time was 12.1 wk (95% CI: 9.7-17.7) (Figure 2A). In general, there were no marked or unexpected differences in PFS time for any of the prognostic variables or characteristics of previous treatment which were considered in the pre-specified subgroup analyses (data not shown).

| Parameter | Patients (n = 123) |

| Response, n (%) | |

| Complete response | 1 (0.8) |

| Partial response | 16 (13.0) |

| Stable disease | 44 (35.8) |

| Progressive disease | 52 (42.3) |

| Not evaluable | 10 (8.1) |

| Objective response (95% CI) | 17 (13.8) (8.3-21.2) |

| Disease control rate (95% CI) | 61 (49.6) (40.5-58.8) |

| PFS | |

| No. of events, n (%) | 117 (95.1) |

| Median PFS time, wk (95% CI) | 12.1 (9.7-17.7) |

| PFS rate, % (95% CI) | |

| 6 wk | 72 (64-80) |

| 12 wk | 50 (41-59) |

| 18 wk | 39 (30-48) |

| 24 wk | 25 (17-33) |

| 30 wk | 17 (10-23) |

| 36 wk | 11 (6-17) |

| Overall survival | |

| No. of events, n (%) | 105 (85.4) |

| Median survival time, mo (95% CI) | 9.5 (7.5-11.6) |

| Survival rate, % (95% CI) | |

| 6 mo | 65 (53-73) |

| 12 mo | 38 (29-46) |

| 18 mo | 25 (18-33) |

| 24 mo | 14 (7-20) |

The median overall survival time was 9.5 mo (95% CI: 7.5-11.6) (Figure 2B), with a 1-year survival rate of 38% (95% CI: 29-46) (Table 3). The median follow-up time for survival was 22.4 mo (95% CI: 21.4-24.4). There were generally no marked or unexpected differences for any of the prognostic variables or characteristics of previous treatment which were considered in pre-specified subgroup analyses of overall survival time (Table 4). A landmark analysis investigated the impact of early occurrence of acne-like rash (during the first 21 d of treatment) on overall survival time. Median overall survival was longer in patients with acne-like rash compared with those patients who experienced no acne-like rash (9.5 mo vs 6.2 mo). Median overall survival time was shorter in patients with grade 3/4 early acne-like rash (4 patients only) compared with grade 1/2 acne-like rash. As the sample size in the subgroup with grade 3/4 acne-like rash was very small, this observation is likely to be an artifact due to differences between patients with and without early acne-like rash with regard to other prognostic factors, such as gender, age and KPS.

| Prognostic factors | n | No. of deaths n (%) | Median survival | |

| Months | 95% CI | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 65 | 92 | 77 (83.7) | 9.6 | (7.9-11.8) |

| ≥ 65 | 31 | 28 (90.3) | 7.5 | (5.7-12.9) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 73 | 64 (87.7) | 9.5 | (7.3-11.7) |

| Female | 50 | 41 (82.0) | 8.9 | (6.4-16.5) |

| Stage based on TMN classification at first diagnosis | ||||

| I/II | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 12.8 | (5.6-14.6) |

| III | 24 | 22 (91.7) | 9.3 | (5.1-11.3) |

| IV | 80 | 67 (83.8) | 9.5 | (7.5-13.0) |

| unknown | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 4.9 | (2.9-NA) |

| Karnofsky performance status | ||||

| ≤ 80 | 39 | 36 (92.3) | 5.7 | (2.6-11.3) |

| > 80 | 84 | 69 (82.1) | 10.3 | (8.9-13.3) |

| No. of previous non-adjuvant lines | ||||

| 1 | 66 | 57 (86.4) | 11.2 | (9.1-13.3) |

| 2 | 37 | 31 (83.8) | 5.9 | (3.8-9.1) |

| ≥ 3 | 20 | 17 (85.0) | 9.3 | (3.6-17.7) |

| Time from end of last course of most recent irinotecan treatment to progression | ||||

| ≤ 30 d | 86 | 76 (88.4) | 8.8 | (7.1-11.3) |

| > 30 d | 37 | 29 (78.4) | 10.6 | (5.7-14.6) |

| Best response of most recent irinotecan schedule1 | ||||

| CR/PR | 20 | 14 (70.0) | 15.6 | (8.6-9.4) |

| PD/SD | 102 | 90 (88.2) | 8.9 | (7.0-11.0) |

| No. of metastatic sites | ||||

| 1 | 51 | 44 (86.3) | 10.6 | (7.9-13.3) |

| ≥ 2 | 72 | 61 (84.7) | 8.4 | (6.9-11.0) |

| BSA | ||||

| ≤ 1.6 m2 | 42 | 34 (81.0) | 8.6 | (6.4-16.5) |

| > 1.6 m2 to ≤ 1.8 m2 | 48 | 41 (85.4) | 10 | (6.9-13.0) |

| > 1.8 m2 | 33 | 30 (90.9) | 9.5 | (5.7-11.8) |

| Early acne-like rash during the first 21 d2 | ||||

| No | 38 | 34 (89.5) | 6.2 | (3.3-11.3) |

| Yes | 85 | 71 (83.5) | 9.5 | (7.2-12.3) |

| Grade 1 or 2 | 81 | 67 (82.5) | 9.6 | (7.4-13.7) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 4 | 4 (100) | 3 | (2.1-10.9) |

The objective response rate was 13.8% (95% CI: 8.3-21.2) (Table 3). The median duration of response was 31.1 wk (95% CI: 18.0-42.6). In addition, 44 patients (35.8%) had stable disease and the disease control rate was 49.6% (95% CI: 40.5-58.8). A higher response rate of 25.0% (5/20 patients) was observed for patients with CR and PR as best response to the most recent irinotecan schedule as compared with subjects with progressive disease and stable disease who had a response rate of 11.8% (12/102 patients). In addition, patients with KPS ≤ 80 at baseline had lower response rates [7.7% (95% CI: 1.6-20.9)] than the KPS > 80 subgroup [16.7% (95% CI: 9.4-26.4)]. There were generally no marked or unexpected differences in response rates between other pre-specified subgroups (data not shown). Disease control rates in the subgroups were consistent with those observed for response rate. The median TTF was 11.7 wk (95% CI, 9.1-17.4).

Ninety patients (73.2%) received post-study anti-cancer treatments, consisting of best supportive care (66 patients; 53.7%), chemotherapy (59 patients, 48.0%), surgery (6 patients, 4.9%), radiotherapy (15 patients, 12.2%) and other treatments (15 patients, 12.2%).

Treatment was generally well tolerated. The most common AEs of any grade according to MedDRA SOC were skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (85.4%), gastrointestinal disorders (85.4%) and general disorders and administration site conditions (44.7%). The most common AEs according to MedDRA preferred terms occurring in at least 20% of the patients were diarrhea (71 patients, 57.7%), rash (70 patients, 56.9%), nausea (55 patients, 44.7%), vomiting (48 patients, 39.0%), anorexia (35 patients, 28.5%), neutropenia (30 patients, 24.4%), constipation (27 patients, 22.0%) and stomatitis (26 patients, 21.1%). Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 68 patients (45.5%) (Table 5). The most common grade 3/4 AEs were diarrhea in 17 patients (13.8%), neutropenia in 11 patients (8.9%) and rash and vomiting both in seven patients (5.7%) (Table 5). Composite AE categories were considered for AEs known to be related to cetuximab, namely infusion-related reactions and acne-like rash (Table 5). Grade 3/4 infusion-related reactions occurred in 3 patients (2.4%; 2 patients with Grade 3, 1 patient with Grade 4). Ten patients (8.1%) had grade 3 acne-like rash (Table 4), with no occurrences of grade 4 rash reported. Overall, 7 patients (5.7%) had AEs that led to the discontinuation of cetuximab and 13 patients (10.6%) had AEs leading to the discontinuation of chemotherapy. Three patients (2.4%) had AEs leading to the discontinuation of both.

| Preferred term | Grade 3 or 4 | Any grade |

| Any, n (%) | 68 (55.3) | 123 (100) |

| Diarrhea | 17 (13.8) | 71 (57.7) |

| Neutropenia | 11 (8.9) | 30 (24.4) |

| Rash | 7 (5.7) | 70 (56.9) |

| Vomiting | 7 (5.7) | 48 (39.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (3.3) | 22 (17.9) |

| Anemia | 4 (3.3) | 12 (9.8) |

| Fatigue | 4 (3.3) | 21 (17.1) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 4 (3.3) | 4 (3.3) |

| Nausea | 4 (3.3) | 55 (44.7) |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 3 (2.4) | 9 (7.3) |

| Dehydration | 3 (2.4) | 4 (0.3) |

| Hypersensitivity | 3 (2.4) | 9 (7.3) |

| Infection | 3 (2.4) | 4 (3.3) |

| Neutrophil count | 3 (2.4) | 3 (2.4) |

| Paronychia | 3 (2.4) | 16 (13.0) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 3 (2.4) | 7 (5.7) |

| Anorexia | 2 (1.6) | 35 (28.5) |

| Constipation | 2 (1.6) | 27 (22.0) |

| Stomatitis | 1 (0.8) | 26 (21.1) |

| Composite AE categories1 | ||

| Infusion-related reactions2 | 3 (2.4) | 19 (15.4) |

| Acne-like rash3 | 10 (8.1) | 99 (80.5) |

At the time of database closure (February 27th, 2009), 105 patients in the ITT/safety population had died, of which 8 died within 30 d after the last dose of study medication. Seven deaths (5.7%) occurred due to disease progression and 1 patient (0.8%) died due to events related to irinotecan-based therapy. There were no deaths related to cetuximab treatment.

The ELSIE study was designed to further investigate, in patients from the Asia-Pacific region, the observations initially made in the BOND study[7] relating to efficacy and safety of the combination of cetuximab with irinotecan in mCRC patients progressing on irinotecan-based chemotherapy. The PFS rate at 12 wk of 50% (95% CI: 41-59) met the expectation for the primary endpoint of the study made at the time of study planning. A sample size of 150 patients was considered sufficient to meet the primary study objective in the current study; however, only 129 patients were actually enrolled. The low recruitment rate in some of the participating countries is thought to be due to the fact that irinotecan was not a preferred treatment option in many of the study centers. Consequently, few patients fulfilled the protocol requirement of having received irinotecan-based treatment as the most recent therapy.

Cross comparisons of the results of this study and similar studies in relation to the interpretations of the efficacy data should be undertaken with some degree of caution, particularly where differences exist in study design[18]. The ELSIE study was comparable in design to the combination arm of the BOND study and the LABEL study[7,15], although all 3 differed slightly in study design from the MABEL study, particularly in the interval for imaging assessment of the tumor[14]. Except for the notable differences in geographical location, there were only minor variations in the patient populations of these studies. Furthermore, the disposition of these populations with respect to the disease under investigation, namely, the number of previous treatment lines, the number of metastatic sites, and best response to most recent irinotecan treatment were considered comparable[7,14,15,19].

A comparison of the treatment outcomes of patients receiving cetuximab in combination with irinotecan-based chemotherapy in the ELSIE, BOND, MABEL and LABEL studies is shown (Table 6). The PFS rate at 12 wk in the present study was slightly lower than that reported in the MABEL and LABEL studies and in the combination therapy arm of the BOND study (PFS rate at 3 mo). The variations across the studies may also reflect differences in the CT scanning schedules for tumor assessment. Tumors were assessed according to modified WHO criteria in these studies every 6 wk by the investigators in the ELSIE and LABEL studies[15], every 12 wk in the MABEL study[14], and every 6 wk by an independent review committee in the BOND study[7]. In addition, differences may reflect other factors relating to patient characteristics, such as different KPS.

| ELSIE | LABEL | MABEL | BOND | |

| Reference | Current study | Buzard et al[15] | Wilke et al[14] | Cunningham et al[7] |

| No. of patients | 123 | 79 | 1147 | 218 |

| Geographical region | Asia-Pacific | Latin America | Europe | Europe |

| Response rate, % (95% CI) | 13.8 (8.3-21.2)1 | 26.6 (17.3-37.7)1 | 20.1 (17.9-22.6)2 | 22.9 (17.5-29.1)3 |

| Disease control rate, % (95% CI) | 49.6 (40.5-58.8)1 | 55.7 (44.1-66.9)1 | 45.2 (42.3-48.2)2 | 55.5 (48.6-62.2)3 |

| Median PFS, wk (95%CI) | 12.1 (9.7-17.7)1 | 17.4 (11.7-18.9)1 | 14.1 (13.0-17.1)1 | 18.0 (12.0-18.0)3 |

| PFS rate at 12 wk, % (95% CI) | 50 (41-59)1 | 57 (46-68)1 | 61 (58-64)1 | 564 (48.7-62.6)3 |

| Median survival, mo (95% CI) | 9.5 (7.5-11.7) | 9.2 (7.9-10.8) | 9.2 (8.6-9.8) | 8.6 (7.9-9.6) |

| OS rate at 1 yr, % (95% CI) | 38 (29-37) | 38 (27-48) | 38 (35-41) | 29 (22-37) |

Consistent with the primary endpoint, tumor response rate and median PFS (12.1 wk) were also slightly lower in the current study than reported in the MABEL and LABEL studies and the combination arm of the BOND study. However, the treatment with cetuximab in combination with irinotecan results translated into very similar overall survival across all four studies in this irinotecan refractory setting (Table 6). Importantly, the median survival time obtained with cetuximab in combination with irinotecan in this and the other studies is in the upper range of results reported for irinotecan or oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/folinic acid in less heavily pre-treated patients[20-24].

The current study demonstrates that cetuximab plus irinotecan is generally well tolerated in patients from the Asia-Pacific region. The most frequently reported grades 3 to 4 AEs were typical for irinotecan (e.g. diarrhea and neutropenia), or cetuximab (e.g. composite AE of acne-like rash). Cetuximab did not appear to increase the incidence or severity of irinotecan-associated AEs and vice versa. Diarrhea was the most common grade 3/4 AE reported in the current study (13.8%), in BOND (21%), MABEL (19%) and LABEL (20%) with neutropenia and rash also frequently observed in each of the studies[7,14,15]. Severe infusion-related reactions occurred in 2.4% of patients in the present study, which is the same proportion as observed in the MABEL study[14]. Interestingly, results from the MABEL study suggest that the incidence of severe infusion-related reactions may be minimized by prophylactic premedication with an antihistamine/corticosteroid combination[25].

In the ELSIE study all-grade and grade 3/4 acne-like rash (composite AE category) were reported in 80.5% and 8.1% of patients respectively, which is comparable with that reported in other studies[14,26]. An association between any early acne-like rash with prolonged overall survival was found. Saltz and colleagues described a correlation between the presence and severity of acne-like rash and survival; median survival in heavily pretreated mCRC patients experiencing no rash was 1.9 mo compared with 9.5 mo in patients experiencing any rash (P = 0.02)[26]. A trend was also observed between the increasing severity of rash and prolonged survival[26]. Comparable results between the presence and severity of acne-like rash with clinical outcome (PFS) have also been reported in the MABEL study[14].

Randomized studies in the first-line treatment of mCRC patients[27,28] and in heavily pretreated mCRC patients[13], have recently demonstrated that the benefit conferred from cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy occurs mainly in patients whose tumors are wild-type for the KRAS gene. In a study of cetuximab plus irinotecan, 5-FU, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for mCRC, patients with KRAS wild-type tumors had a response rate of 59.3% compared with 36.2% in those with mutated KRAS tumors[27]. These data led to revised guidance from regulatory and advisory authorities concerning the administration of cetuximab only to patients with KRAS wild-type mCRC. Thus KRAS mutation testing of tumors should be routine clinical practice when cetuximab is to be administered in this setting. At the time of the ELSIE study design this knowledge was not available and therefore material was not collected for tumor KRAS testing. This might suggest that the benefit observed from combining cetuximab with irinotecan in unselected patients with mCRC in the current study would be smaller than the effect in patients with KRAS wild-type tumors. The future tailoring of this cetuximab-containing regimen to selected patients is therefore likely to enhance the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of treatment in this patient population.

To conclude, the ELSIE study has demonstrated that the combination of cetuximab with irinotecan is well tolerated and active in mCRC patients from Asia and Australia. The efficacy and safety profiles of the combination are similar to those described in previous studies in European and Latin American patient populations. The use of cetuximab and irinotecan may be particularly beneficial in patients with wild-type KRAS, and further studies in this patient population are warranted.

The incidence and mortality rates for colorectal cancer (CRC) in Eastern and South-East Asia are increasing. Patients with metastatic CRC (mCRC) who progress following first-line therapy have few treatment options. This open-label, phase II study evaluated the efficacy and safety of cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory mCRC patients from South-East Asia and Australia.

Research in the field of mCRC has recently focused on the development of targeted therapies in disease treatment. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is frequently expressed in mCRC and is associated with tumor growth and metastasis. Cetuximab is an EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody which binds EGFR inhibiting its activity. Registration of cetuximab was based on the pivotal BOND trial in which patients with mCRC progressing on an irinotecan-containing regimen achieved a higher overall survival rate when cetuximab was added to irinotecan compared with irinotecan alone. The subsequent Monoclonal Antibody Erbitux in a European Pre-License Study (MABEL) and Latin American Erbitux Pre-License Study (LABEL) studies confirmed the efficacy of this treatment combination in a community-based setting.

The safety and efficacy of cetuximab in combination with irinotecan in mCRC patients failing on irinotecan-containing regimens has been demonstrated in phase II studies. The ELSIE study supports these findings in patients from the Asia-Pacific region. Median overall survival was comparable with that reported in the LABEL and MABEL studies and the combination arm of the BOND study. There were slightly lower tumor response rates, median PFS and PFS rate at 12 wk in the ELSIE study. Patients were unselected in the ELSIE and the observed treatment benefit may be greater in patients selected for KRAS wild-type tumors.

The results of this study confirm the activity of cetuximab in combination with irinotecan in patients with mCRC from Asia and Australia. In the future cetuximab-containing regimens are likely to be tailored to selected patients in this setting with KRAS wild-type tumors.

The paper on the whole is well written and the abstract reflects the basic design and findings.

Peer reviewer: John Beynon, BSc, MB BS, MS, FRCS (ENG), Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Singleton Hospital, Sketty Lane, Swansea, SA28QA, United Kingdom

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN. Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide, vol. Version 1.0, 2004: IARC Press, 2002. . |

| 2. | Van Cutsem E, Nordlinger B, Adam R, Köhne CH, Pozzo C, Poston G, Ychou M, Rougier P. Towards a pan-European consensus on the treatment of patients with colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2212-2221. |

| 3. | Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, Grothey A, Vauthey JN, Nagorney DM, McWilliams RR. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677-3683. |

| 4. | Center MM, Jemal A, Ward E. International trends in colorectal cancer incidence rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1688-1694. |

| 5. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871-876. |

| 6. | Adenis A, Aranda Aguilar E, Robin YM, Miquel R, Penault-Llorca F, C . C, Queralt B, Eggleton SP, van den Berg N, Wilke H. Expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR or HER1) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in a large scale metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23 suppl:A3630. |

| 7. | Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, Bets D, Mueser M, Harstrick A, Verslype C. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337-345. |

| 8. | Folprecht G, Lutz MP, Schöffski P, Seufferlein T, Nolting A, Pollert P, Köhne CH. Cetuximab and irinotecan/5-fluorouracil/folinic acid is a safe combination for the first-line treatment of patients with epidermal growth factor receptor expressing metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:450-456. |

| 9. | Goldstein NS, Armin M. Epidermal growth factor receptor immunohistochemical reactivity in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage IV colon adenocarcinoma: implications for a standardized scoring system. Cancer. 2001;92:1331-1346. |

| 10. | Mayer A, Takimoto M, Fritz E, Schellander G, Kofler K, Ludwig H. The prognostic significance of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, epidermal growth factor receptor, and mdr gene expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:2454-2460. |

| 11. | Baselga J. The EGFR as a target for anticancer therapy--focus on cetuximab. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 4:S16-S22. |

| 12. | Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, Scheithauer W, Abubakr YA, Lutz MP, Vega-Villegas ME, Eng C, Steinhauer EU, Prausova J. EPIC: phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2311-2319. |

| 13. | Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD, Robitaille S. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757-1765. |

| 14. | Wilke H, Glynne-Jones R, Thaler J, Adenis A, Preusser P, Aguilar EA, Aapro MS, Esser R, Loos AH, Siena S. Cetuximab plus irinotecan in heavily pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer progressing on irinotecan: MABEL Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5335-5343. |

| 15. | Buzaid AC, Mathias Cde C, Perazzo F, Simon SD, Fein L, Hidalgo J, Murad AM, Esser R, Senger S, Lerzo G. Cetuximab Plus irinotecan in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer progressing on irinotecan: the LABEL study. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9:282-289. |

| 16. | Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29-41. |

| 17. | Greenwood M. The natural duration of cancer. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. 1926;33:1-26. |

| 18. | Levine MN, Julian JA. Registries that show efficacy: good, but not good enough. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5316-5319. |

| 19. | Wilke H, Buzaid A, Mathias C, Lim R, Esser R, Loos A, Van Cutsem E, Cunningham D. Cetuximab in combination with irinotecan in patients after irinotecan failure: An integrated analysis of four studies from different geographic regions. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:suppl: A4062. |

| 20. | Fuchs CS, Moore MR, Harker G, Villa L, Rinaldi D, Hecht JR. Phase III comparison of two irinotecan dosing regimens in second-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:807-814. |

| 21. | Cunningham D, Pyrhönen S, James RD, Punt CJ, Hickish TF, Heikkila R, Johannesen TB, Starkhammar H, Topham CA, Awad L. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1413-1418. |

| 22. | Rougier P, Van Cutsem E, Bajetta E, Niederle N, Possinger K, Labianca R, Navarro M, Morant R, Bleiberg H, Wils J. Randomised trial of irinotecan versus fluorouracil by continuous infusion after fluorouracil failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1407-1412. |

| 23. | Rothenberg ML, Eckardt JR, Kuhn JG, Burris HA 3rd, Nelson J, Hilsenbeck SG, Rodriguez GI, Thurman AM, Smith LS, Eckhardt SG. Phase II trial of irinotecan in patients with progressive or rapidly recurrent colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1128-1135. |

| 24. | Rougier P, Bugat R, Douillard JY, Culine S, Suc E, Brunet P, Becouarn Y, Ychou M, Marty M, Extra JM. Phase II study of irinotecan in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer in chemotherapy-naive patients and patients pretreated with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:251-260. |

| 25. | Siena S, Glynne-Jones R, Adenis A, Thaler J, Preusser P, Aguilar EA, Aapro MS, Loos AH, Esser R, Wilke H. Reduced incidence of infusion-related reactions in metastatic colorectal cancer during treatment with cetuximab plus irinotecan with combined corticosteroid and antihistamine premedication. Cancer. 2010;116:1827-1837. |

| 26. | Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJ Sr, Needle MN, Kopit J, Mayer RJ. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1201-1208. |

| 27. | Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G, Stroh C. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663-671. |

| 28. | Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D’Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408-1417. |