Published online Mar 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1642

Revised: December 13, 2010

Accepted: December 20, 2010

Published online: March 28, 2011

AIM: To compare the outcome of surgical treatment of colorectal adenocarcinoma in elderly and younger patients.

METHODS: The outcomes of 122 patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical treatment between January 2004 and June 2009 were analyzed. The clinicopathological and blood biochemistry data of the younger group (< 75 years) and the elderly group (≥ 75 years) were compared.

RESULTS: There were no significant differences between the two groups in operation time, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, time to resumption of oral intake, or morbidity. The elderly group had a significantly higher rate of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. The perioperative serum total protein and albumin levels were significantly lower in the elderly than in the younger group. The serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was lower in the elderly than in the younger group, and there was a significant decreasing trend after the operation in the elderly group.

CONCLUSION: The short-term outcomes of surgical treatment in elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma were acceptable. Surgical treatment in elderly patients was considered a selectively effective approach.

- Citation: Jin L, Inoue N, Sato N, Matsumoto S, Kanno H, Hashimoto Y, Tasaki K, Sato K, Sato S, Kaneko K. Comparison between surgical outcomes of colorectal cancer in younger and elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(12): 1642-1648

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i12/1642.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1642

Colorectal adenocarcinoma is one of the most common malignant diseases worldwide, and colorectal adenocarcinoma is also the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in developed countries. Moreover, the incidence of colorectal adenocarcinoma has been reported to increase with age in the some countries[1-3]. According to the published statistical data, the incidence of colorectal adenocarcinoma in elderly patients has been increasing slightly over the past several decades, and especially in people aged > 75 years old in Japan[4]. Surgery has always been the main curative treatment for colorectal adenocarcinoma, which can be resected curatively for primary tumor lesions and lymph node dissection. As a result of preexisting comorbidity in elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma, there is controversy as to whether surgical treatment is beneficial. The average life expectancy in many developed countries is reported to be > 80 years[5], and the number of colorectal adenocarcinoma patients is expected to increase in the future, therefore, the issue of the treatment of elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma needs to be addressed. Some studies on surgery for colorectal adenocarcinoma in the elderly have been published[6-12], but not a sufficient number.

The survival rate and quality of life after surgical treatment of colorectal adenocarcinoma are affected by postoperative complications. To clarify the impact of surgery on elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma, we investigated and evaluated the short-term results of surgical treatment for colorectal adenocarcinoma in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years, in comparison with those < 75 years.

We studied 122 patients with pathologically diagnosed colorectal adenocarcinoma who were treated surgically at the Northern Fukushima Medical Center in Japan between January 2004 and June 2009. The patients were divided into two groups according to age: an elderly group of 54 patients aged ≥ 75 years, and a younger group of 68 patients aged < 75 years. All operations were performed by experienced surgeons in our hospital, and none of the patients received chemoradiotherapy before surgery. Operation time, intraoperative blood loss, length of postoperative hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality were analyzed to compare the risks and benefits of surgery in the two groups, and the two groups were compared with regard to blood examination data before and after surgery.

All of the patients were investigated routinely by physical examination, colonoscopy, colorectal contrast radiography, and thoracoabdominal computed tomography. Preoperative risk and preexisting comorbidity was evaluated using the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) scoring system. The results of surgical treatment and tumor staging were evaluated according to the International Union against Cancer tumor-node-metastasis classification, followed by pathological examination of the surgical specimen.

Information concerning the clinical characteristics of the patients upon admission was collected from the medical records. The general nutritional status of the patients was assessed on the basis of their body mass index (BMI), and their serum total protein and albumin levels. The tumor index, which was calculated by multiplying the longest diameter of the lesion by its shortest diameter, was used to evaluate the tumor. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level were measured by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) before and after the operation. Systematic inflammatory response was assessed on the basis of the white blood cell (WBC) count and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level at different times before and after surgery.

Laparoscopic-assisted colectomy for patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma was still assessed. The anastomoses were made with a circular stapler when the single-stapler technique was used, and with gastrointestinal anastomotic devices when functional end-to-end anastomosis was performed after both laparoscopic-assisted and open colectomy.

Postoperatively, oral intake of clear liquids was started after flatus was detected, provided the patient did not have severe nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distention, and a liquid diet was given, provided the patient had no trouble with the clear liquid regimen. Patients were discharged when a solid diet was well accepted and no postoperative complications were detected. Their length of postoperative hospital stay was measured from the day of surgery to the day they were discharged.

All data are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses for the categorical variables were performed by means of the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for measured variables. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

One hundred and twenty-two patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma were treated by surgery, and 115 (94.3%) patients were evaluated by postoperative pathologically. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1. Of the 68 patients in the younger group, 40 (58.8%) were male, and 28 (51.9%) patients in the elderly group were male. The age range was 40-74 years in the younger group and 75-94 years in the elderly group. BMI was 22.23 ± 3.25 kg/m2 in the younger group and 21.08 ± 3.58 kg/m2 in the elderly group, and it was significantly lower in the elderly group than in the younger group (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the two groups for site of colon tumor, lesion type, tumor index, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, or pathological stage. Laparoscopic-assisted colectomy was performed in 35 (64.8%) patients in the elderly group as opposed to 19 (27.9%) in the younger group, and the percentage of patients treated by laparoscopic-assisted colectomy was significantly higher in the elderly group. Only one patient in the elderly group had 30-d surgical mortality. The numbers of lymph nodes harvested, proximal and distal to the tumor site are shown in Table 2, and there were no significant differences between the two groups.

| Younger group (n = 68) | Elderly group (n = 54) | P value | ||

| Sex | NS | |||

| Male/female | 40 (58.8)/28 (41.2) | 28 (51.9)/26 (48.1) | ||

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) | 62.2 ± 8.6 | 80.4 ± 5.0 | NS | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 22.2 ± 3.3 | 21.1 ± 3.6 | 0.035 | |

| Localization of tumor lesion | NS | |||

| C | 3 (4.4) | 3 (5.6) | ||

| A | 9 (13.2) | 18 (33.3) | ||

| T | 8 (11.8) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| D | 3 (4.4) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| S | 26 (38.2) | 11 (20.4) | ||

| R | 20 (29.4) | 14 (25.9) | ||

| ASA | 0.01 | |||

| I | 39 (57.4) | 12 (22.2) | ||

| II | 22 (32.4) | 31 (57.4) | ||

| III | 6 (8.8) | 11 (20.4) | ||

| IV | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Type of tumor | NS | |||

| 0 | 6 (8.8) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| 1 | 6 (8.8) | 7 (13.0) | ||

| 2 | 52 (76.5) | 44 (81.5) | ||

| 3 | 5 (7.4) | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Histological type | NS | |||

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.7) | ||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1/tub2) | 29 (42.6)/33 (48.5) | 17 (31.5)/28 (51.9) | ||

| Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | 3 (4.4) | 5 (9.3) | ||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 2 (2.9) | 2 (3.7) | ||

| T Stage | NS | |||

| T1 (m, sm) | 0 (0)/7 (10.3) | 1 (1.9)/2 (3.7) | ||

| T2 (mp) | 15 (22.1) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| T3 (ss, a) | 16 (23.5)/14 (20.6) | 19 (35.2)/9 (16.7) | ||

| T4 (se, si, ai) | 13 (19.1)/3 (4.4)/0 (0) | 11 (20.4)/4 (7.4)/0 (0) | ||

| N Stage | NS | |||

| N0 | 39 (57.4) | 30 (55.6) | ||

| N1 | 21 (30.9) | 13 (24.1) | ||

| N2 | 4 (5.9) | 5 (9.3) | ||

| NX | 4 (5.9) | 6 (11.1) | ||

| Metastases | NS | |||

| M0 | 61 (89.7) | 49 (90.7) | ||

| M1 | 7 (10.3) | 5 (9.3) | ||

| Stage | NS | |||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| I | 17 (25.0) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| II | 20 (29.4) | 22 (40.7) | ||

| III | 23 (33.8) | 17 (31.5) | ||

| IV | 8 (11.8) | 6 (11.1) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Overall | Present | 27 (39.7) | 36 (66.7) | 0.003 |

| Absent | 41 (60.3) | 18 (33.3) | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | Present | 6 (8.8) | 14 (25.9) | 0.011 |

| Absent | 62 (91.2) | 40 (74.1) | ||

| Hypertension | Present | 10 (14.7) | 19 (35.2) | 0.008 |

| Absent | 58 (85.3) | 35 (64.8) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Present | 5 (7.4) | 3 (5.6) | NS |

| Absent | 63 (92.6) | 51 (94.4) | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | Present | 3 (4.4) | 5 (9.3) | NS |

| Absent | 65 (95.6) | 49 (90.7) | ||

| Other diseases | Present | 6 (8.8) | 7 (13.0) | NS |

| Absent | 62 (91.2) | 47 (87.0) |

| Younger group (n = 68) | Elderly group (n = 54) | P value | |

| Tumor size index (cm2) | 15.7 ± 12.0 | 22.8 ± 20.2 | NS |

| Lesion circulation (%) | 74.0 ± 26.9 | 75.3 ± 27.7 | NS |

| Operation time (min) | 137.4 ± 45.7 | 120.4 ± 35.1 | NS |

| Operative blood loss (mL) | 138.4 ± 166.2 | 140.4 ± 198.8 | NS |

| Postoperative stay (d) | 23.2 ± 14.3 | 24.6 ± 14.5 | NS |

| Blood transfusion | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 8 (14.8) | |

| No | 68 (100.0) | 46 (85.2) | |

| Procedure of surgery | NS | ||

| Cecum resection | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Right hemicolectomy | 16 (23.5) | 24 (44.4) | |

| Transverse colon resection | 2 (2.9) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Left hemicolectomy | 4 (5.9) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 22 (32.4) | 9 (16.7) | |

| Anterior resection | 16 (23.5) | 9 (16.7) | |

| Hartmann’s resection | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Mile’s resection | 5 (7.4) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Lymph node dissection | NS | ||

| D0 | 4 (5.9) | 7 (13.0) | |

| D1 | 10 (14.7) | 7 (13.0) | |

| D2 | 31 (45.6) | 30 (55.6) | |

| D3 | 23 (33.8) | 10 (18.5) | |

| Number of lymph nodes resected | 12.1 ± 9.0 | 11.3 ± 8.6 | NS |

| Distal margin distance (mm) | 61.0 ± 40.4 | 62.2 ± 40.9 | NS |

| Proximal margin distance (mm) | 96.8 ± 47.6 | 93.4 ± 57.9 | NS |

| Morbidity | NS | ||

| Surgical site infection | NS | ||

| Yes | 5 (7.4) | 7 (13.0) | |

| No | 63 (92.6) | 47 (87.0) | |

| Anastomotic leakage | NS | ||

| Yes | 4 (5.9) | 3 (5.6) | |

| No | 64 (94.1) | 51 (94.4) | |

| Others | NS | ||

| Yes | 8 (11.8) | 6 (11.1) | |

| No | 60 (88.2) | 48 (88.9) |

The surgical procedures used and pathological characteristics of the resected tumors are also shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups for surgical procedure. After resecting the lesion, the double-stapler technique, single-stapler technique, and functional end-to-end anastomosis were performed for reconstruction in both groups, and colostomy was performed after the Mile’s approach. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in reconstruction methods and no statistically significant differences between them in operation time, intraoperative blood loss, surgical site infection, or anastomotic leakage. Although the difference between the intraoperative blood loss in the two groups was not significant, a significantly higher percentage of patients in the elderly group required a postoperative blood transfusion (P < 0.01).

After surgical treatment, the percentage of patients who could drink water before postoperative day 3 was 78% (53/68) in the younger group, compared to 72.2% (39/54) in the elderly group. The number of patients who received the liquid diet before postoperative day 4 was 46 (67.7%) in the younger group and 34 (63.0%) in the elderly group. There were no significant differences between the two groups for the time after surgery when a clear liquid or a liquid diet was started.

There was a preexisting comorbidity, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cerebrovascular disease, in 36 (66.7%) patients in the elderly group. Eleven (20.4%) patients in the elderly group were assessed as worse than ASA II at the time of operation, compared to seven (10.3%) patients in the younger group (Table 1), and the difference between the groups was statistically significant. The mean length of postoperative hospital stay was 23.24 ± 14.27 d in the younger group and 24.59 ± 14.48 d in the elderly group. Although the comorbidity rate was higher in the elderly group, the length of postoperative hospital stay was not significantly longer than in the younger group.

Right hemicolectomy and sigmoid colon resection were performed in one patient in the elderly group, because the lesions were located in the ascending and sigmoid colon. Furthermore, six patients in the younger group underwent a synchronous operation, including cholecystectomy, inguinal hernia operation, ovariectomy, and partial liver resection for liver metastasis, and two patients in the elderly group underwent synchronous cholecystectomy. Postoperative complications in the younger group consisted of surgical site infection in five patients, anastomotic leakage in four, and other morbidity, such as anastomotic bleeding, abscess in the peritoneal cavity, and wound rupture, whereas in the elderly group they consisted of anastomotic leakage in three patients, surgical site infection in seven, and anastomotic bleeding, abscess in the abdominal cavity, pancreatitis, necrosis of the stoma, and ileus in one each. There was no significant difference in the operation-related morbidity between the two groups. We compared the proximal and distal distances from the tumor lesion, lesion circulation rate, total number of lymph nodes dissected, and times after surgery when the clear liquid and liquid diets were begun, but there were no significant differences between the two groups in surgical outcomes evaluated on this basis.

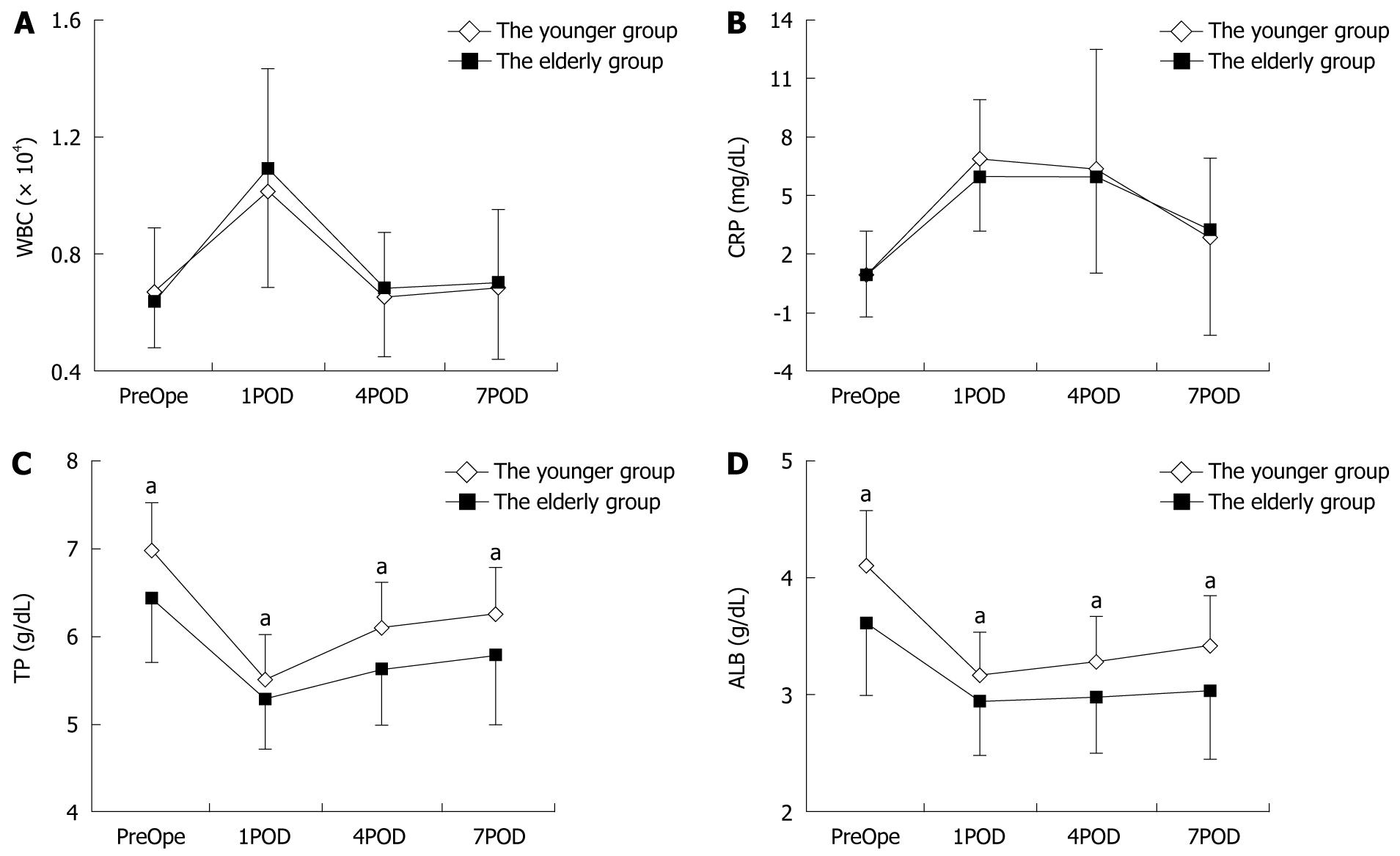

The severity of the systematic inflammatory response before and after surgery was assessed on the basis of WBC count and serum C-reactive protein level in the younger and elderly groups (Figure 1). On postoperative day (POD) 1, the mean WBC count and C-reactive protein level were 10 092.39 ± 3258.60/mL and 6.88 ± 3.02 mg/dL, respectively, in the younger group and 10 866.67 ± 3480.92/mL and 5.98 ± 2.84 mg/dL, respectively, in the elderly group. Although the WBC count on POD 1 was higher in the elderly group, the difference between the two groups was not significant. After POD 1, the WBC count and CRP level gradually decreased in both groups, and there were no significant differences between the two groups in either parameter on POD 4 or POD 7.

The perioperative nutritional status of the patients was assessed on the basis of their serum total protein level, serum albumin level and BMI. The total serum protein and serum albumin levels before and after surgery are shown in Figure 1, and the BMI values before the operation are shown in Table 1. The serum total protein and albumin levels preoperatively were 6.97 ± 0.55 and 4.08 ± 0.49 g/dL, respectively, in the younger group and 6.42 ± 0.73 and 3.61 ± 0.61 g/dL, respectively, in the elderly group, and the nadirs of both of these parameters in both groups were recorded on POD 1. The nutritional status of the patients based on their BMI, serum total protein level, and serum albumin level was poorer in the elderly group than in the younger group, and the differences in all three parameters between the younger group and the elderly group were statistically significant.

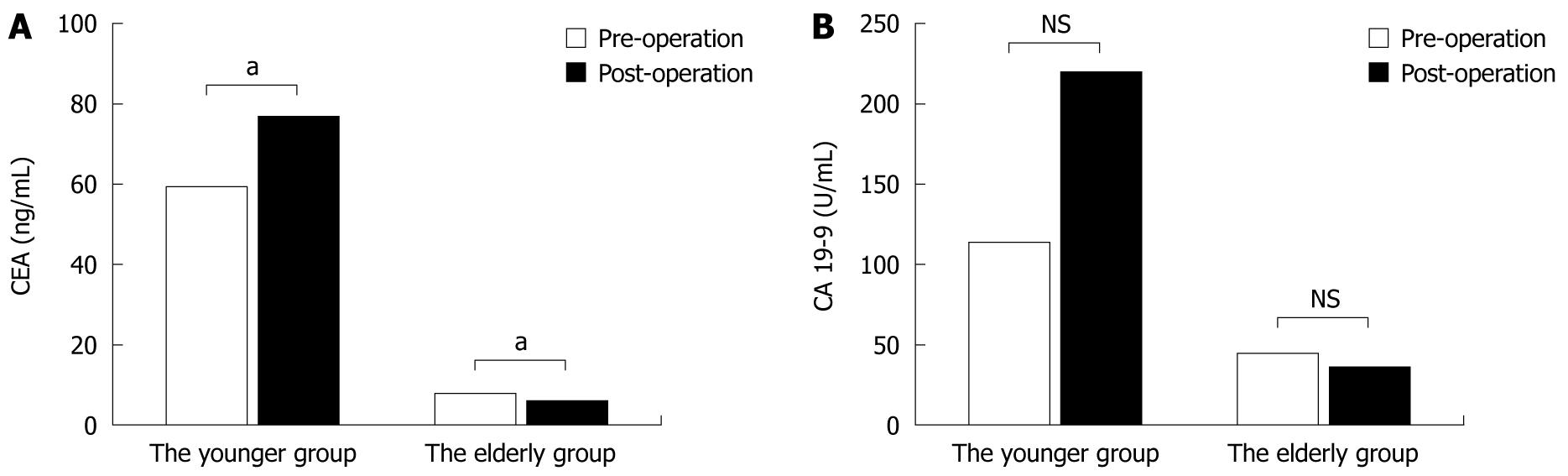

The serum CEA and CA19-9 levels were measured before and after surgery (Figure 2). The mean serum CEA and CA19-9 levels in the younger group were 59.52 ± 374.69 ng/mL and 113.24 ± 381.16 U/mL, respectively, before surgery and 77.05 ± 494.09 ng/mL and 221.85 ± 1186.01 U/mL after surgery. In the younger group, the serum CEA and CA19-9 levels were higher after the operation than before. By contrast, the mean serum CEA and CA19-9 levels in the elderly group were 8.22 ± 15.37 ng/mL and 45.24 ± 194.35 U/mL, respectively, before surgery and 6.65 ± 18.83 ng/mL and 36.78 ± 137.65 U/mL, respectively, after surgery, and both were lower after surgery than before. There were significant differences in the level of CEA in the younger and elderly groups perioperatively.

We compared the short-term outcomes of surgical treatment of colorectal adenocarcinoma in younger and elderly groups. Of the 122 patients included in this study, 54 (44.3%) were aged ≥ 75 years old, and the oldest patient was 94 years old. The patients in the elderly group had a high incidence of preexisting comorbidity, therefore, the effect of surgery for colorectal adenocarcinoma was unclear, except in those who had colon obstruction or bleeding caused by the tumor. The patients in the elderly group had other diseases, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and cerebrovascular disease. Although preoperative status evaluated by the ASA scoring system was worse in the elderly group than in the younger group, almost all of the patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma could be treated with surgery.

There were no significant differences between the younger and the elderly groups with regard to operative factors, including bowel-margin-positive rate, tumor index, number of lymph nodes harvested, extent of lymph node dissection, intraoperative blood loss, or operation time. This could partly explain why the elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma could be treated curatively by surgery if they were managed appropriately before and after the operation. Curative colectomy could not be performed in four patients in the elderly group because of distant metastasis and local deep invasion. Thus, the rate of diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the early stage needs to be improved, especially in high-risk populations.

It has been reported that preoperative nutritional status can greatly affect the postoperative complications of the colorectal carcinoma patients after surgery[13]. The serum albumin and total protein levels, and BMI were assessed to evaluate the nutritional status of the patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma, and there was a significantly higher prevalence of hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia in the elderly group than in the younger group, before and after surgery. Although the nutritional status of the patients in the elderly group was poorer than in the younger group, the percentages of patients with anastomotic leakage and wound infection in the elderly group were not significantly higher. Our results suggest that hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia do not affect the recovery of elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma after surgical treatment, if they are appropriately managed during the perioperative period. Dixon et al[14] have found that patients with a low albumin level have a significantly shorter survival time after surgery for colorectal adenocarcinoma, and that the long-term outcomes of surgery need to be examined to establish the essential benefits of surgery in elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma.

A relationship between the systematic inflammatory response and survival has been reported in colorectal cancer patients who have undergone curative surgery[15]. In the present study, the systematic inflammatory response was evaluated on the basis of the perioperative WBC count and serum CRP level between the two groups, and there was no significant difference between the severity of the systematic inflammatory response in the elderly and younger groups. These results suggested that the postoperative survival rate of the elderly patients was no worse than that of the younger patients, and that surgical treatment was acceptable for patients who could endure the operation, regardless of their age.

CEA and CA19-9 are the tumor-associated antigens that are most commonly used in the management of colorectal adenocarcinoma. It has been reported that CEA is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that plays a pivotal role in such biological phenomena as adhesion, immunity, and apoptosis of tumor cells, and in the assessment of sensitivity to antitumor agents[16,17]. Moreover, some previous studies have shown an association between high preoperative serum CEA level and poor outcome[18,19] of colorectal adenocarcinoma patients who underwent surgical treatment. In the present study, the serum CEA levels were significantly lower in the elderly group preoperatively and postoperatively. Moreover, the serum CEA levels exhibited a significantly decreasing trend after surgical treatment in the elderly group (P < 0.05), whereas the serum CEA levels in the younger patients were significantly higher after surgery than before (P < 0.05). These results suggest that surgical treatment might be beneficial and be one of the selectively effective strategies for elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Some studies have found that CA19-9 level is a prognostic factor for colorectal cancer patients[20,21]. In the present study, the serum CA19-9 levels in the elderly group were lower than in the younger group, and the levels in the elderly group showed a decreasing trend after surgical treatment, but not in the younger group. These findings also suggested that the elderly patients benefited more from surgical treatment.

The elderly population was considered to be a high-risk group for malignant diseases, and the prognosis of elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma treated by surgery was estimated to be worse than for younger patients, especially for emergency surgery. The relation between emergency and elective surgery in patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma was not compared in this study. Furthermore, the number of the patients enrolled in this study was small, therefore, the results were limited. A larger sample study is needed to establish the effect of surgical treatment in elderly and younger patients.

In conclusion, the short-term outcomes of surgical treatment of elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma in this study were acceptable. Surgical treatment of elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma was considered a selectively effective approach.

Colorectal adenocarcinoma is one of the most common malignant diseases worldwide, and colorectal adenocarcinoma is also the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in developed countries. Moreover, the incidence of colorectal adenocarcinoma has been reported to increase with age in some countries. Some articles on surgery for colorectal adenocarcinoma in the elderly have been published, but their number has not been sufficient.

To clarify the impact of surgery on elderly patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma, the authors investigated and evaluated the short-term results of surgical treatment for colorectal adenocarcinoma in elderly patients ≥ 75 years old in comparison with patients < 75 years old.

There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to surgery-related factors. However, serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was lower in the elderly than in the younger group, and there was a significant decreasing trend after surgery in the elderly group.

The present study is helpful in initiating further clinical studies to validate the results. Furthermore, the use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment instrument to determine operative risk could assist with selection of elderly patients who are most likely to benefit from surgery, and make the results of future studies more generalizable.

Peer reviewer: Jakob Robert Izbicki, MD, PhD, Department of General Surgery, University of Hamburg, Martinistr 52, Hamburg D-20246, Germany

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a systematic review. Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356:968-974. |

| 2. | Jung B, Påhlman L, Johansson R, Nilsson E. Rectal cancer treatment and outcome in the elderly: an audit based on the Swedish Rectal Cancer Registry 1995-2004. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:68. |

| 3. | Haberland J, Bertz J, Wolf U, Ziese T, Kurth BM. German cancer statistics 2004. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:52. |

| 4. | Available from: http://ganjoho.ncc.go.jp/professional/statistics/statistics.html. |

| 5. | Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html. |

| 6. | McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Davis KA, Longo WE. Factors predicting morbidity and mortality in emergency colorectal procedures in elderly patients. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1157-1162. |

| 7. | Pedrazzani C, Cerullo G, De Marco G, Marrelli D, Neri A, De Stefano A, Pinto E, Roviello F. Impact of age-related comorbidity on results of colorectal cancer surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5706-5711. |

| 8. | Holt PR, Kozuch P, Mewar S. Colon cancer and the elderly: from screening to treatment in management of GI disease in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:889-907. |

| 9. | Allardyce RA, Bagshaw PF, Frampton CM, Frizelle FA, Hewett PJ, Rieger NA, Smith JS, Solomon MJ, Stevenson AR. Australasian Laparoscopic Colon Cancer Study shows that elderly patients may benefit from lower postoperative complication rates following laparoscopic versus open resection. Br J Surg. 2010;97:86-91. |

| 10. | Basili G, Lorenzetti L, Biondi G, Preziuso E, Angrisano C, Carnesecchi P, Roberto E, Goletti O. Colorectal cancer in the elderly. Is there a role for safe and curative surgery? ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:466-470. |

| 11. | Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Truán N, Pire G, Alvarez P. Emergency surgery for complicated colorectal carcinoma: a comparison of older and younger patients. Int Surg. 2007;92:320-326. |

| 12. | Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, Steinert R, Ueberrueck T, Bittner R, Berg E, Engemann R, Gellert K, Arbogast R. The impact of the risk factor "age" on the early postoperative results of surgery for colorectal carcinoma and its significance for perioperative management. World J Surg. 2005;29:1013-1021; discussion 1021-1022. |

| 13. | Schwegler I, von Holzen A, Gutzwiller JP, Schlumpf R, Mühlebach S, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk is a clinical predictor of postoperative mortality and morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:92-97. |

| 14. | Dixon MR, Haukoos JS, Udani SM, Naghi JJ, Arnell TD, Kumar RR, Stamos MJ. Carcinoembryonic antigen and albumin predict survival in patients with advanced colon and rectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:962-966. |

| 15. | Roxburgh CS, Salmond JM, Horgan PG, Oien KA, McMillan DC. The relationship between the local and systemic inflammatory responses and survival in patients undergoing curative surgery for colon and rectal cancers. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2011-2018; discussion 2018-2019. |

| 16. | Hammarström S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:67-81. |

| 17. | Duffy MJ. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a marker for colorectal cancer: is it clinically useful? Clin Chem. 2001;47:624-630. |

| 18. | Huh JW, Oh BR, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level as an independent prognostic factor in potentially curative colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:396-400. |

| 19. | Wanebo HJ, Rao B, Pinsky CM, Hoffman RG, Stearns M, Schwartz MK, Oettgen HF. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:448-451. |

| 20. | Kouri M, Pyrhönen S, Kuusela P. Elevated CA19-9 as the most significant prognostic factor in advanced colorectal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1992;49:78-85. |

| 21. | Nozoe T, Rikimaru T, Mori E, Okuyama T, Takahashi I. Increase in both CEA and CA19-9 in sera is an independent prognostic indicator in colorectal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:132-137. |