Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1343

Revised: November 3, 2010

Accepted: November 10, 2010

Published online: March 14, 2011

AIM: To search for the optimal surgery for gastrinoma and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.

METHODS: Sixteen patients with genetically confirmed multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) underwent resection of both gastrinomas and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) between 1991 and 2009. For localization of gastrinoma, selective arterial secretagogue injection test (SASI test) with secretin or calcium solution was performed as well as somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) and other imaging methods such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The modus of surgery for gastrinoma has been changed over time, searching for the optimal surgery: pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was first performed guided by localization with the SAST test, then local resection of duodenal gastrinomas with dissection of regional lymph nodes (LR), and recently pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy (PPTD) has been performed for multiple duodenal gastrinomas.

RESULTS: Among various types of preoperative localizing methods for gastrinoma, the SASI test was the most useful method. Imaging methods such as SRS or CT made it essentially impossible to differentiate functioning gastrinoma among various kinds of NETs. However, recent imaging methods including SRS or CT were useful for detecting both distant metastases and ectopic NETs; therefore they are indispensable for staging of NETs. Biochemical cure of gastrinoma was achieved in 14 of 16 patients (87.5%); that is, 100% in 3 patients who underwent PD, 100% in 6 patients who underwent LR (although in 2 patients (33.3%) second LR was performed for recurrence of duodenal gastrinoma), and 71.4% in 7 patients who underwent PPTD. Pancreatic NETs more than 1 cm in diameter were resected either by distal pancreatectomy or enucleations, and no hepatic metastases have developed postoperatively. Pathological study of the resected specimens revealed co-existence of pancreatic gastrinoma with duodenal gastrinoma in 2 of 16 patients (13%), and G cell hyperplasia and/or microgastrinoma in the duodenal Brunner’s gland was revealed in all of 7 duodenal specimens after PPTD.

CONCLUSION: Aggressive resection surgery based on accurate localization with the SASI test was useful for biochemical cure of gastrinoma in patients with MEN 1.

- Citation: Imamura M, Komoto I, Ota S, Hiratsuka T, Kosugi S, Doi R, Awane M, Inoue N. Biochemically curative surgery for gastrinoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1343-1353

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1343

Controversy has surrounded the treatment strategy for gastrinoma and neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES)[1-14]. It has been confirmed that ZES in patients with MEN 1 is caused mostly by duodenal gastrinomas[15,16]. Some surgeons have not recommended surgery for duodenopancreatic gastrinoma, because of both low biochemical cure rate of gastrinoma and early recurrence of gastrinoma after surgery[8,9]. In contrast, surgeons who have performed aggressive duodenopancreatic resection have reported a higher biochemical cure rate of gastrinoma after surgery, although these studies included relatively small numbers of patients[4-7,11-14].

We have performed curative resection surgery for gastrinoma in 41 patients with ZES guided by localization using the selective arterial secretagogue injection test (SASI test)[17,18]. Guided by localization with the SASI test, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was performed for 10 patients, of whom 3 patients were classified as MEN 1, and all of them have been cured of gastrinoma postoperatively. Pathological examination of the duodenopancreatic specimens resected from the MEN 1 patients revealed single or multiple gastrinomas < 10 mm only in the duodenum, but not in the pancreas head. Thus, we have changed the modus of resection surgery for gastrinomas in patients with MEN 1 from PD to transduodenal excisions of the duodenal gastrinomas or partial duodenectomy (LR) with dissection of the regional lymph nodes, while seeking for less invasive and optimal surgical resection for gastrinomas in MEN 1 patients. Recently, we have performed pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy (PPTD) for MEN 1 patients with multiple gastrinomas and/or numerous microgastrinomas in the duodenum[19,20]. Here, we report the results of our surgical strategy for both gastrinoma and pancreatic NETs in MEN 1 patients, and discuss the optimal surgery for patients with MEN 1 and gastrinomas from a viewpoint of the staging of both gastrinoma and pancreatic NET in these patients.

Sixteen patients with genetically confirmed MEN 1 and gastrinoma underwent resection surgery for gastrinomas and pancreatic NETs by a team comprising a chief surgeon (senior author) and co-surgeons (co-authors) at the Departments of Surgery of Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Osaka Saiseikai Noe Hospital and Kansai Electric Production Company Hospital between March 1991 and March 2010.

All patients were examined for MEN 1 gene mutations by a co-author (MK) at the Medical Gene Research Center, Kyoto University. A diagnosis of ZES was established by confirming the co-existence of gastric hyperacidity and hypergastrinemia. Levels of gastrin were > 80 pg/mL in patients who had undergone distal or total gastrectomy and > 200 pg/mL in patients who had not undergone distal gastrectomy[21]. Gastric hyperacidity was confirmed using 24 h pH monitoring, and was diagnosed when the percentage of the time that the gastric pH was 0-4 was > 70%[21]. Either the secretin test or the calcium test was performed for all patients[22-24]. The secretin test was performed by bolus intravenous injection of secretin (3 U/kg body weight). Blood samples were collected from a cubital vein before and 2, 4, and 6 min after secretin injection. An increase in serum immunoreactive gastrin concentration (IRG) both of > 20% of the basal serum IRG and > 80 pg/mL, 4 min after secretin injection was considered positive. The calcium test was performed by injecting 1.17 mEq calcium solution (1 mL of 0.39 mEq calcium gluconate hydrate) diluted with 2 mL physiological saline over 30 s into a cubital vein[22-24]. The intraoperative secretin test was performed using the same method as the preoperative secretin test, and results were obtained within 60 min using rapid radioimmunoassay of serum gastrin levels[25].

For localization of gastrinoma, the SASI test with secretin (Secrepan® 30 units) or calcium solution (0.39 mEq calcium gluconate diluted with 2 mL physiological saline) was performed for all patients as described previously[17,18,26]. The principle of the SASI test is to identify the feeding artery of gastrinoma by stimulating gastrinoma to release gastrin using a secretagogue[17]. We used secretin until 2004, since then we have used calcium gluconate hydrate solution, because production of secretin in Japan ended in 2004[10]. CT, MRI or US have been used primarily for detection of distant metastases, such as hepatic metastases or large lymph nodes[1,10,11].

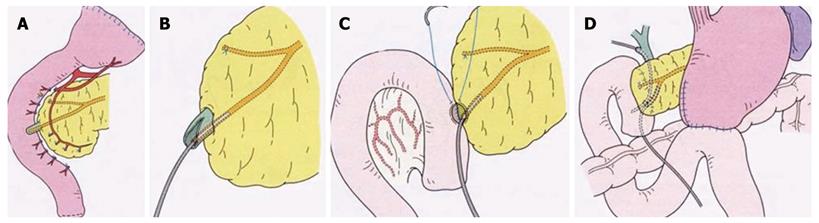

PPTD was performed using a new technique described elsewhere[20]; briefly, when resecting the entire duodenum, only a mucosectomy is performed on the duodenal major papilla portion, retaining the structure of the major papilla, and after an 8 mm long sphincterotomy, the opened papilla is anastomosed to the incisional opening of the jejunum[20]. Details of the procedure are shown in Figure 1.

Resected duodenopancreatic tissues including any suspected NETs or lymph nodes were fixed in a 10% formalin solution and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with Masson-Fontana, Grimelius, and Hellerstrom-Hellman silver stains. Immunohistochemical staining was performed with Simple Stain MAX-PI (Multi) (mouse and rabbit/horseradish peroxidase) reagent (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) using polyclonal rabbit anti-human gastrin serum (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Cure of gastrinoma was defined as a normal fasting serum IRG < 150 pg/mL in patients without a history of gastrectomy and < 80 pg/mL in patients with a history of gastrectomy, and/or a negative secretin test or a negative calcium test during the 6 mo follow-up surveillance period. Survival curve analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Between 1991 and 1997, PD was performed for 3 patients with ZES based on localization guided only by the SASI test, because imaging methods (CT, MRI, US) did not visualize any tumor in the abdomen (Table 1). In 3 patients, the SASI test localized the gastrinoma in the upper part of the duodenum and/or the head of the pancreas, thus PD was performed for all patients. Preoperative localization by the SASI test was correct, and gastrinomas were proved in the duodenum; that is, 7 duodenal gastrinomas in 1 patient (No. 2) and only 1 duodenal gastrinoma in 2 patients (Nos. 1 and 3). Metastatic lymph nodes associated with the duodenal gastrinoma were identified in 2 patients. Two patients (Nos. 1 and 2) had multiple nonfunctioning NETs in the head of the pancreas (Table 1). The preoperative serum IRG of these patients ranged between 310 and 800 pg/mL, and the postoperative serum IRG decreased in all patients to < 33 pg/mL. The postoperative secretin test was negative in all patients. One patient died of other causes 4 year after undergoing the PD. Two patients are alive and well, and biochemical cure of gastrinoma has continued for 18 year 5 mo and 12 year, postoperatively.

| No. | Age | Gender | ZES | Ulcerdiseases | Ulcer related operation | MEN 1 related diseases | Pre-PD IRG (pg/mL) | Localization of gastrinoma | Operation | Post-PD IRG (pg/mL) | Gastrinoma | Metastases | PancreasNET | Prognosis present status(post-op yr) | Postoperative secretin or calcium test | |||||

| SASI | GIF | CT | Location | Number | Size (mm) | N | L | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 44 | M | + | DU 1984 | - | Pit NET 1987 | 310 | GDA IPDA | ND | ND | PitX 1989 Mar | 26 | D | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 5 | Alive well with Pit NET, PNET(18 yr 5 mo) | Negative |

| T PitX 1990 Mar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PD 1991 Mar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 39 | F | + | GU perf 1982 | GX 1982 | HPT 1991 Nov | 800 | GDA IPDA | ND | ND | PD, PX 1991 Mar St ParX | 33 | D | 7 | 1- 7 | 1 | 0 | 6 | DOD(4 yr) no recur | Negative |

| Ileus 1983 | JX 1983 | |||||||||||||||||||

| JU 1990 | 1991 Nov | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 21 | M | + | DU, GU 1997 | - | Pit NET 1997 | 583 | GDA | ND | ND | PD 1997 Aug PitX 1997 Oct | 25 | D | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Alive wll (12 yr) no recur | Negative |

Since 1996, 5 patients have successively undergone local resection of duodenal gastrinoma through duodenectomy after a 7 year intermission. 1 patient (No. 9) underwent DX in 2009 based on localization by the SASI test, duodenoscopy revealed duodenal submucosal NETs in 3 patients, and CT visualized a few metastatic lymph nodes more than 2 cm with a pancreatic NET more than 1 cm in 2 patients (Table 2). Localization by the SASI test was correct in all of them. In case No. 9, gastrinoma was located not only in the duodenum, but also in the head of the pancreas. Size of duodenal gastrinoma was between 1-15 mm in diameter. Any pancreatic NETs > 1 cm were treated by enucleation and/or distal pancreatectomy. In 3 patients, metastatic lymph nodes were associated with duodenal gastrinoma.

| No. | Age | Gender | ZES | Ulcer diseases | Ulcer related operation | MEN 1 related diseases | Pre-first duodenectomy IRG (pg/mL) | Localization of gastrinoma | Operation | Post-duodenectomy IRG (pg/mL) | Gastrinoma | Metastases | Pancreas NETs | Prognosis present status (post-op yr) | Postoperativesecretin or calcium test | |||||

| SASI | GIF | CT | Location | Number | Size (mm) | N | L | |||||||||||||

| 4 | 49 | M | + | GU 1984 | GX 1984 | HPTPit NET | 3,180 | GDA | ND | PNET | DX, DP, St ParX 1996 Sep | 50 | D | 9 | 1-7 | 0 | 0 | 1(gluc) | Alive well, after TParX (2004 Jul) PitX (2006 Oct) (13 yr 10 mo) | Negative |

| JU 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 61 | F | + | GU 1974 | GX 1974 | HPT | 400 | GDA | ND | ND | St Par X 1984 Apr | 230 → 140 | D | 5 | 2-4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Alive well, (14 yr 4 mo) no recur | Negative |

| ↓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| JU 1975 | JX 1975 | 230 | GDA | ND | ND | DX 1996 Apr | ||||||||||||||

| (post Par X) | DX 2004 Nov | 170 → 70 | D | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | 56 | F | + | DU 1997 | - | HPT | 580 | GDA | ND | ND | PX 1997 Feb | 885 → 68 | D | 3 | 1-2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Alive well, with mult PNET (9 yr 8 mo) | Negative |

| ↓ | St Par X 1999 Jul | |||||||||||||||||||

| 385 → 885 | DX 2001 Jan | |||||||||||||||||||

| (post Par X) | DX 2007 Jan | 400 → 54 | D | 2 | 1-3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | 44 | F | + | GU 1992 | - | PNET | PPPD 1993 Jan | 137 | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 1 | Alive well,(9 yr 4 mo) no recur | Negative | ||||

| HPT | St Par X 1993 Apr | |||||||||||||||||||

| 811 | GDA | Dsmt | ND | DX 2001 Apr | 811 → 28 | D | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| 8 | 33 | M | - | - - | - | HPT | 3240 | GDA | Dsmt | ND | ParX 1993 | 44 | D | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | mult (gluc) | Alive well, (7 yr) No recur | Negative |

| St ParX 2003 May | ||||||||||||||||||||

| DX, DP 2003 Jul | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 54 | F | + | GU, DU 2005 | - | Ins (multi) | DP 1978 | 149 | D | 2 | 6, 12 | 3 | 0 | 1 | Alive well, (1 yr 6 mo) no recur | Negative | ||||

| HPT | 49 500 | n n | Dsmt | Dsmt | TParX, TX 1989 | |||||||||||||||

| Pit NET | Gsmt | Gsmt | PitX,γ-K 1989, 1995 | P(H) | 1 | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| GNET | LNMets | DX, GX, LNX 2009 Feb | ||||||||||||||||||

Most of these patients were biochemically cured of gastrinoma after the first LR, but ZES recurred in 2 patients (Nos. 5 and 6). In patient No. 5, the serum IRG increased from 140 to 170 pg/mL 8 year postoperatively, and in patient No. 6, the serum IRG increased from 68 to 400 pg/mL 6 year postoperatively. Based on localization by the SASI test, a second LR was performed for these patients, and their serum IRG levels decreased to within normal ranges postoperatively. They have been biochemically cured of gastrinoma since the second LR for 5 year, 8 mo and 2 year, 7 mo, respectively, postoperatively.

Patient No. 9 had undergone a distal pancreatectomy for multiple insulinoma 31 year before visiting our clinic. She also had a history of a total parathyroidectomy with a forearm subcutaneous parathyroid transplantation and gamma knife therapy for a pituitary NET. Her serum IRG was 49 500 pg/mL. Multiple submucosal gastric NETs and multiple duodenal submucosal NETs were identified by gastroduodenoscopic examination. A few large metastatic lymph nodes around the head of the pancreas were visualized using CT; therefore, advanced stage of gastrinoma was suspected. The SASI test localized the gastrinoma in the duodenum and/or the head of the pancreas. We performed LR and an enucleation NET in the head of the pancreas with dissection of the peripancreatic lymph nodes. A partial resection of the middle part of the stomach for multiple gastric tumors was also performed. Her serum IRG decreased to < 150 pg/mL and plasma chromogranin A concentration was normalized. Pathological examination revealed 3 duodenal gastrinomas and 1 pancreatic gastrinoma with 3 metastatic lymph nodes from duodenopancreatic gastrinoma. The gastric NET was a type II NET.

PPTD was first performed for case No. 10, in whom a substantial numbers of NETs were palpated intraoperatively and a few large metastatic lymph nodes were detected, without any pancreatic head tumors. Pathological study revealed numerous submucosal microgastrinomas throughout the duodenum. Her serum IRG did not decrease to within normal range and she developed hepatic metastases 3 year after the PPTD. In order to save the head of the pancreas, PPTD was performed for the following 6 patients in whom the SASI test diagnosed gastrinoma in the pancreatic head and/or the duodenum and considerable numbers of duodenal NETs were suspected during surgery (Table 3). In one patient (case 16) the SASI test localized gastrinoma not only in the head of the pancreas and/or the duodenum, but also in the tail of the pancreas, so PPTD and a distal pancreatectomy were performed curatively, and the patient has since been free of gastrinoma. Any serious postoperative morbidity was experienced in this series of patients.

| No. | Age | Gender | ZES | Ulcer diseases | Ulcer related operation | MEN 1 related diseases | Pre-PPTD IRG (pg/mL) | Localization of gastrinoma | Operation | Post-PPTD IRG (pg/ mL) | Gastrinoma | Metastases | Pancreas NETs | Prognosis (post-op yr) | Post-PPTD secretin or calcium test | ||||||

| SASI | GIF | CT | Location | Number | Size (mm) | N | L | ||||||||||||||

| 10 | 51 | F | + | DU 1997 Dec | - | HPT | 54 800 | GDA, IPDA | ND | #6 LN #13 LN | St ParX 2003 | 216 | D | num | 1-4 | 2 | 0 | 9 (1; gluc) | Alive well with L Mets (IRG 900) (6 yr 8 mo) | Positive | |

| ↓ | Apr | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 200 | PPTD, DP 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (post ParX) | Nov | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | 30 | M | - | - | - | HPT | 820 | GDA, IPDA | ND | PNET (uncus tail) | T ParX, TX 2004 Apr | 110 | D | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Alive well (6 yr) no recur | Negative | |

| ↓ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pit NET | 206 | PPTD, DP 2004 Jul | |||||||||||||||||||

| (post ParX) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 33 | M | + | DU 2004 Mar | - | HPT | 3050 | GDA, IPDA | Dsmt | ND | T ParX, TX | 57 | D | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | multi | Alive well (6 yr) no recur | Negative | |

| ↓ | 2003 Aug | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 710 | PPTD, DP 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (post ParX) | Aug | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | 48 | F | - | - | - | HPT | 687 | IPDA, DPA | Dsmtdiff PNET (D-EUS) | #13LN PNET (< 3 mm) diff | PPTD 2007 Apr | 59 | D | num | 1-5 | 1 | 0 | multi | Alive well (2 yr 11 mo) no recur | Negative | |

| T ParX, TX 2007 Sep | diff | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | 33 | M | + | JU perf 2007 Jan | Patch | HPT | 13 900 (post ParX) | GDA | Dsmtdiff PNET (D-EUS) | #17LN Dsmt | T ParX, TX 2001 Dec | 255 | D | 1 | 8 | 2 | 0 | multi | Alive well witn N Mets (IRG 371) (2 yr 8 mo) | Positive | |

| PPTD 2007 Nov | diff | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | 57 | F | + | DU perf 2006 Jan | GX | HPT | 720 | GDA, IPDA | ND | ND | T ParX, TX 2007 Mar | 42 | D | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Alive well (2 yr) no recur | Negative | |

| JU perf 2006 Jul | JX | ↓ | PPTD, TG 2008 Aug | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ileus 2007 May | 646 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| JU perf 2008 Jul | (post ParX) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 32 | M | + | Es bleeding 2002 Oct | HPT | 1630 | DGA, SPA | ND | PNET (17 mm) | ParX, PPTD P(T)X | 2008 Aug | 450 | D, P(T) | 3, 1 | 3, 10, 11 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 (> 5 mm) | Alive well (2 mo) no recur | Negative | |

| DU JU perf 2006 Jan | |||||||||||||||||||||

| JX | 1000 | DGA, SPA | ND | PNET (5-10 mm) | DP, P(H)X | 2009 Jul | 94 | P(b) | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | multi | ||||||||

| JU perf 2008 Nov | GX, JX | ||||||||||||||||||||

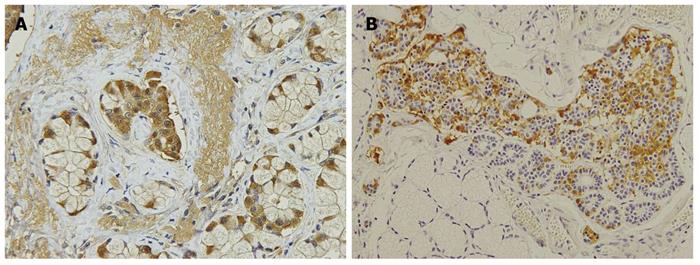

In 7 PPTD patients, duodenal gastrinomas were numerous in only 2 patients, and there were 4 or more in 2 additional patients. In 3 other patients, only 1 tumor was diagnosed as gastrinoma, and the other submucosal tumors were mostly diagnosed as hyperplasia of the duodenal Brunner’s gland. Not expecting these results, we carefully re-examined the duodenal mucosal membrane with anti-gastrin antibody and identified clusters of gastrin-producing cells in or adjacent to the Brunner’s gland, some of which were diagnosed as microgastrinoma. The clusters of gastrin-producing cells were found in all 7 duodenal specimens after PPTD (Figure 2).

Five patients post-PPTD have been cured of gastrinoma for lengths of time ranging from 2 year to 6 year 8 mo. However, in 2 patients in whom their preoperative serum IRG levels were as high as 18 200 pg/mL or 13 900 pg/mL after parathyroidectomy, and advanced stages of gastrinoma were suspected, PPTD was noncurative (Table 3). In one of them, hepatic metastases have become apparent on CT film within 3 year postoperatively, and in the other patient, distant lymph nodes metastases have developed.

Of the 16 patients in this series, 7 patients had single duodenal gastrinoma and 9 patients had multiple gastrinomas. More specifically, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 9 duodenal gastrinomas were detected in 1 patient each; 7 duodenal gastrinomas in 2 patients; and numerous duodenal gastrinomas in 2 patients. In 2 patients (13%), pancreatic gastrinoma co-existed with duodenal gastrinoma which were localized by the SASI test.

To date, 14 patients have been cured of gastrinoma and 2 patients have been noncurative, postoperatively. The overall patient survival curve is shown in Figure 3A, with a survival rate of 90.9% at 10 years. The gastrinoma-free survival curve is shown in Figure 3B, with a survival rate of 82.0% at 10 years.

Controversy has surrounded the treatment strategy for gastrinoma and pancreatic NET in patients with MEN 1 and ZES[1-14]. It is difficult to determine whether aggressive surgical resection of both gastrinoma and pancreatic NETs improves survival rates and the long term biochemical cure of gastrinoma in MEN 1 patients, because of the rarity of the disease[1-4,10-14]. Many recently published articles support aggressive surgery, such as PD or multiple LR of a few duodenal gastrinomas and distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic NETs, for both biochemical cure of gastrinoma and prolongation of survival[1,4,10-14]. On the other hand, Gibril et al[27] reported the results of an important prospective study on the natural history of gastrinoma in patients with MEN 1, in which 57 patients with MEN 1 and ZES were followed for 8 year without performing surgical resection for duodenopancreatic NETs until the tumors grew to > 2.5 cm. In this study, 13 patients (23%) developed hepatic metastases and 3 patients died of duodenopancreatic NETs. They suggested that biochemical cure of gastrinoma might be impossible in patients with MEN 1 and that prolongation of survival of MEN 1 patients with an aggressive type of NETs would not be realized until the development of a tool to differentiate an aggressive type of NET from another slow growing type of NET. Their results themselves, we think, support the idea that early resection should be necessary for decreasing the rate of hepatic metastases from duodenopancreatic NETs in MEN 1 patients.

The present study shows that aggressive surgical resection for gastrinoma in MEN 1 patients using PD or aggressive LR, or PPTD guided by localization with the SASI test, was useful for long term biochemical cure of duodenopancreatic gastrinoma, and that aggressive resection of pancreatic NETs was also useful for prevention of hepatic metastases. So, we would like to recommend early aggressive surgical resection of duodenopancreatic NETs for MEN 1 patients.

Goudet et al[28] performed a cohort study of 758 patients with MEN 1 and found that gastrinoma was a statistically significant high-risk factor for death of patients with MEN 1 secondary to the nonfunctioning pancreatic NETs, and suggested earlier resection surgery for both gastrinoma and nonfunctioning pancreatic NETs in patients with MEN 1. Gauger and Thompson reported a 94% 15 year survival rate of patients with functioning NETs (gastrinoma or insulinoma) in MEN 1 patients after local resections of duodenal gastrinomas and a distal pancreatectomy with enucleations of NETs in the head of the pancreas without any operative morbidity[2]. These results suggest that early resection of gastrinoma in MEN 1 patients is useful for normalization of serum gastrin levels and prevention of distant metastases.

Identification of gastrinoma among multiple NETs in the duodenopancreatic region of patients with MEN 1 is essentially impossible by imaging techniques alone[17,18]. The SASI test localizes gastrinomas or metastatic lymph nodes by judging whether or not gastrin is secreted from NETS in the area of interest by stimulation with a secretagogue, so it can differentiate functioning gastrinoma among multiple NETs in MEN 1 patients.

On the other hand, SRS and other imaging methods [CT or MRI or ultrasonography (US)] are useful for identification of hepatic metastases, although it is difficult to tell the absence of gastrinoma in the area of interest. We have used secretin for stimulating gastrinoma to release gastrin during the SASI test for a long time, but now we use calcium gluconate hydrate solution (Calcicol®), because secretin has not been produced in Japan since 2004. We compared the results with both secretagogues and found the results were identical[21].

In 1991, imaging methods were not sensitive for visualizing < 1 cm gastrinoma; thus we performed resection surgery of both gastrinoma and microgastrinoma based on localization with the SASI test. When the SASI test localized gastrinomas in the feeding area of the gastroduodenal artery, we performed PD. In the first 3 patients with MEN 1, the SASI test localized < 1 cm gastrinomas in the head of the pancreas and/or the duodenum, so we performed PD for them and all of them were cured of gastrinoma; 2 patients have been alive and healthy for more than 12 year, although a patient died of other causes 4 year postoperatively (Table 1). In the resected specimens of the first 3 patients, < 1 cm gastrinomas were located only in the duodenum and not in the pancreas. In those days, endocrine surgeons working in the USA or EU gradually found that the gastrinomas in patients with MEN 1 were localized mostly in the duodenum and rarely in the pancreas[15,16]. Thompson et al have started to perform LR for duodenal gastrinoma and distal pancreatectomy with enucleation of NET in the head of the pancreas in MEN 1 patients[1]. According to our results and theirs, we also started to perform local excisions of duodenal gastrinomas and enucleation or a distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic NETs, which are less invasive compared to PD. Since then, 6 patients have undergone LR for duodenal gastrinomas, which has been successful in all patients, although in 2 patients duodenal gastrinoma recurred and second LR was performed 8 year 8 mo and 6 year after the first LR.

We performed PPTD for 7 patients in whom duodenal gastrinomas were thought to number more than 5 during surgery. The duodenal gastrinomas were numerous in only 2 of 7 patients and the duodenal tumors in the other 5 patients were mostly diagnosed as hyperplasia of the duodenal Brunner’s glands postoperatively (Table 3). Not expecting these results, we immunohistochemically stained the duodenal wall with anti-gastrin antibody and found a cluster of gastrin-producing cells or microgastrinomas in or adjacent to the Brunner’s gland. The clusters of gastrin-producing cells in the Brunner’s gland were found in all of the duodenal specimens after PPTD.

Klöppel et al[29] have reported that in patients with MEN 1, mutations in the menin gene can cause hyperplasia of gastrin-producing cells in the duodenal Brunner’s glands, which are the precursor lesion of gastrinoma. Our results are consistent with their report. Thus, in the duodenum of MEN 1 patients with substantial numbers of duodenal gastrinomas and/or microgastrinomas, de novo gastrinoma might develop during the patient’s lifetime.

Of the 16 patients in the present study, 7 patients (43.8%) had 1 duodenal gastrinoma and 9 patients (56.2%) had multiple duodenal gastrinomas. Gastrinoma did not recur in patients belonging to the former group, but recurred in 2 patients (22.2%) belonging to the latter group who had 3 and 5 duodenal gastrinomas, respectively. PPTD may be useful for preventing both residual microgastrinoma and recurrence due to development of de novo duodenal gastrinoma in MEN 1 patients with substantial numbers of gastrinomas and microgastrinomas.

In 7 patients who underwent PPTD, no postoperative complications, such as pancreatic leakage, acute pancreatitis, abscess or surgical site infections, have been experienced. Thus, PPTD is less invasive surgery compared to PD. On the other hand, dissection of the regional l ymph nodes may be incomplete by PPTD compared to PD. As duodenal gastrinoma metastasizes to the regional lymph nodes independent of size, any regional lymph nodes around both the pancreas head and the common hepatic artery have to be dissected. Lymph nodes along the superior mesenteric artery have to be resected when they are palpated hard[20].

When considering the optimal surgery for patients with MEN 1 and gastrinoma, we must first seriously consider the risk of hepatic metastases from pancreatic NETs[1,7-9,14,28,30]. Hepatic metastases from pancreatic NETs are more serious than those from duodenal gastrinoma, and the rate of hepatic metastases from pancreatic NETs is at least several times more frequent than those from duodenal NETs[6,7,16,28,30]. Thus, we recommend distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic NETs with enucleations of NETs in the pancreatic head more than 1 cm, as recommended by Thompson[1].

As for optimal surgical resection for sporadic duodenal NET, recently several articles have dealt with the subject relating to the staging of duodenal nonfunctioning NETs. Evans’s group have performed a retrospective analysis of patients with duodenal NETs operated at their institute and they proposed a standard strategy for duodenal NETs using a staging based on the depth of tumor invasion and the grading of the development of the distant metastases[31]. Sarr’s group also published a similar study[32]. Both groups recommended endoscopic excisions for duodenal NET smaller than 1 cm, and open transduodenal resection with dissection of the regional lymph nodes for duodenal NET between 1 cm and 2 cm, because rate of lymph node metastases cannot be ignored in duodenal NET between 1 and 2 cm in diameter. Both groups recommended PD for duodenal NET more than 2 cm with lymph node metastases[31,32]. However, both groups intentionally excluded duodenal gastrinoma from their retrospective analytical studies, because the natural history of duodenal gastrinoma seemed quite different from other duodenal NETs, which suggested a more aggressive progression of duodenal gastrinoma[31,32].

In our study, 7 of 16 patients had only 1 duodenal gastrinoma, but 3 of the 7 patients had metastatic lymph nodes, and 1 of them (No. 14) had distant metastases resulting in noncurative resection of gastrinoma (Table 3). So, instead of endoscopic excision, local resection with dissection of lymph nodes may be recommended for a few < 1 cm duodenal gastrinomas in MEN 1 patients[1,2]. For substantial numbers of < 1 cm duodenal gastrinomas with multiple pancreatic NETs in MEN 1 patients, we would like to recommend PPTD with distal pancreatectomy and enucleation of > 1 cm NETs in the head of the pancreas, because cure of duodenal gastrinoma is not likely to be achieved for a long time due to both possible residual microgastrinoma and development of de novo gastrinomas in the duodenum[20,29]. PD might be indicated for MEN 1 patients with a substantial number of both duodenal gastrinomas and metastatic regional lymph nodes with a few > 1 cm pancreatic NETs. Of course, curative resection has to be indicated before development of hepatic micrometastases.

In this series, only one patient has died of other diseases and the other patients have been alive and well to date. Overall survival curve of the patients is shown in Figure 3A. Evaluating together with the gastrinoma-free survival curve of these patients (Figure 3B), we would like to conclude that resection surgery was useful for cure of gastrinoma and prolongation of survival of the patients with MEN 1 and gastrinoma.

Given that pancreatic gastrinoma co-existed with duodenal gastrinoma in 12.5% of our patients, caution is advised, because many surgeons and pathologists have believed that pancreatic gastrinoma is rare in MEN 1 patients[33]. To date, total pancreatectomy has rarely been performed for MEN 1 patients, but we think that total pancreatectomy may be indicated for a few MEN 1 patients according to decisions based on the clinicopathological genetic analysis of pancreatic NET in such patients[34].

In conclusion, aggressive resection surgery based on accurate localization was useful for biochemical cure of gastrinoma in patients with MEN 1 and gastrinoma. Given that pancreatic gastrinoma co-existed with duodenal gastrinomas in 2 of 16 patients (13%), we would like to recommend the SASI test for preoperative localization of gastrinoma in MEN 1 patients.

Treatment strategy for gastrinoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) has been controversial. Most doctors have thought that gastrinomas in MEN 1 cannot be cured because curative resection is rare and recurrence rate is high, and pancreatectomy for pancreatic NETs in MEN 1 does not make sense, since NETs and micro-NETs exist diffusely in the pancreas. On the other hand, recent reports by a few aggressive surgeons show that a high cure rate of gastrinomas and long term prolongation of survival have been achieved by aggressive surgery. For achieving curative resection of gastrinomas in MEN 1, correct localization of gastrinomas is essential for guiding curative surgery, and in order to prolong the life of patients with MEN 1 and duodenopancreatic NETs, surgical resection of these NETs before development of hepatic metastases is essential, because hepatic metastases is the most significant prognostic factor.

The authors should select an optimal modus of surgery for curing gastrinoma and pancreatic NETs in MEN 1 patients, otherwise surgery may end non-curatively or may become too invasive to ensure quality of life for patients. For the best balance between curability of surgery and postoperative good quality of life, the best modus of surgery should be applied for patients with MEN 1 and gastrinoma by estimating the stage of duodenopancreatic NETs.

The present study shows that cure of gastrinomas in MEN 1 patients can be obtained when you resect gastrinomas guided by localization with the SASI test, and prevention of hepatic metastases can be obtained by resection of > 1 cm pancreatic NETs by pancreatectomy of enucleations. As for the modus of surgery, we are the first to propose pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy (PPTD) for multiple or numerous duodenal gastrinomas in MEN 1 as the optimal extent of aggressive surgery. The authors have also proved that pancreatic gastrinoma co-exists with duodenal gastrinoma in 13% of patients with MEN 1, although recently most surgeons and some pathologists have reported that gastrinomas exist only in the duodenum in MEN 1 patients.

By understanding the fact that curative surgical resection is possible by correct localization, and by further development of clinicopathological genetic analysis of the disease, the optimal surgical strategy corresponding to the stage of the disease will be established for gastrinomas and duodenopancreatic NETs in MEN 1 patients in the near future.

PPTD is the modus of surgery by which total duodenum is resected without resecting pancreas tissue. Traditionally, for resecting malignant tumors in the duodenum, pancreatoduodenectomy has been used by which one third of the pancreas is resected with the duodenum.

The study evaluates the standard surgery for patients with gastrinoma in MEN 1 guided by accurate preoperative localization.

Peer reviewer: Leonidas G Koniaris, Professor, Alan Livingstone Chair in Surgical Oncology, 3550 Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (310T), 1475 NW 12th Ave, Miami, FL 33136, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Thompson NW. Current concepts in the surgical management of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 pancreatic-duodenal disease. Results in the treatment of 40 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, hypoglycaemia or both. J Intern Med. 1998;243:495-500. |

| 2. | Gauger PG, Thompson NW. Early surgical intervention and strategy in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;15:213-223. |

| 3. | Wilson SD, Krzywda EA, Zhu YR, Yen TW, Wang TS, Sugg SL, Pappas SG. The influence of surgery in MEN-1 syndrome: observations over 150 years. Surgery. 2008;144:695-701; discussion 701-702. |

| 4. | Hausman MS Jr, Thompson NW, Gauger PG, Doherty GM. The surgical management of MEN-1 pancreatoduodenal neuroendocrine disease. Surgery. 2004;136:1205-1211. |

| 5. | Fendrich V, Langer P, Celik I, Bartsch DK, Zielke A, Ramaswamy A, Rothmund M. An aggressive surgical approach leads to long-term survival in patients with pancreatic endocrine tumors. Ann Surg. 2006;244:845-851; discussion 852-853. |

| 6. | Tonelli F, Fratini G, Nesi G, Tommasi MS, Batignani G, Falchetti A, Brandi ML. Pancreatectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related gastrinomas and pancreatic endocrine neoplasias. Ann Surg. 2006;244:61-70. |

| 7. | Kouvaraki MA, Shapiro SE, Cote GJ, Lee JE, Yao JC, Waguespack SG, Gagel RF, Evans DB, Perrier ND. Management of pancreatic endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg. 2006;30:643-653. |

| 8. | Triponez F, Goudet P, Dosseh D, Cougard P, Bauters C, Murat A, Cadiot G, Niccoli-Sire P, Calender A, Proye CA. Is surgery beneficial for MEN1 patients with small (< or = 2 cm), nonfunctioning pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumor? An analysis of 65 patients from the GTE. World J Surg. 2006;30:654-662; discussion 663-664. |

| 9. | Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, Venzon DJ, Libutti SK, Doppman JL, Fraker DL, Norton JA, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Analysis of factors associated with long-term (five or more years) cure in patients undergoing operation for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery. 1998;124:1160-1166. |

| 10. | Imamura M, Komoto I, Ota S. Changing treatment strategy for gastrinoma in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 2006;30:1-11. |

| 11. | Bartsch DK, Langer P, Wild A, Schilling T, Celik I, Rothmund M, Nies C. Pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: surgery or surveillance? Surgery. 2000;128:958-966. |

| 12. | Lairmore TC, Chen VY, DeBenedetti MK, Gillanders WE, Norton JA, Doherty GM. Duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2000;231:909-918. |

| 13. | You YN, Thompson GB, Young WF Jr, Larson D, Farley DR, Richards M, Grant CS. Pancreatoduodenal surgery in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: Operative outcomes, long-term function, and quality of life. Surgery. 2007;142:829-836; discussion 836.e1. |

| 14. | Bartsch DK, Fendrich V, Langer P, Celik I, Kann PH, Rothmund M. Outcome of duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2005;242:757-764, discussion 764-766. |

| 15. | Pipeleers-Marichal M, Somers G, Willems G, Foulis A, Imrie C, Bishop AE, Polak JM, Häcki WH, Stamm B, Heitz PU. Gastrinomas in the duodenums of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:723-727. |

| 16. | Imamura M, Kanda M, Takahashi K, Shimada Y, Miyahara T, Wagata T, Hashimoto M, Tobe T, Soga J. Clinicopathological characteristics of duodenal microgastrinomas. World J Surg. 1992;16:703-709; discussion 709-710. |

| 17. | Imamura M, Takahashi K, Adachi H, Minematsu S, Shimada Y, Naito M, Suzuki T, Tobe T, Azuma T. Usefulness of selective arterial secretin injection test for localization of gastrinoma in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1987;205:230-239. |

| 18. | Imamura M, Takahashi K, Isobe Y, Hattori Y, Satomura K, Tobe T. Curative resection of multiple gastrinomas aided by selective arterial secretin injection test and intraoperative secretin test. Ann Surg. 1989;210:710-718. |

| 19. | Imamura M, Komoto I. Resection surgery for gastrinomas in patients with MEN 1 and ZES guided by selective arterial secretagogue injection test. World J Surg. 2009;33 Suppl 1:S67. |

| 20. | Imamura M, Komoto I, Doi R, Onodera H, Kobayashi H, Kawai Y. New pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy technique. World J Surg. 2005;29:203-207. |

| 21. | Imamura M, Komoto I. Gastrinoma. Y. editors. Endocrine Surgery: Principles and Practice (Springer Specialist Surgery Series). London: Springer Verlag 2009; 507-521. |

| 22. | Frucht H, Howard JM, Slaff JI, Wank SA, McCarthy DM, Maton PN, Vinayek R, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. Secretin and calcium provocative tests in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:713-722. |

| 23. | Itami A, Kato M, Komoto I, Doi R, Hosotani R, Shimada Y, Imamura M. Human gastrinoma cells express calcium-sensing receptor. Life Sci. 2001;70:119-129. |

| 24. | Wada M, Komoto I, Doi R, Imamura M. Intravenous calcium injection test is a novel complementary procedure in differential diagnosis for gastrinoma. World J Surg. 2002;26:1291-1296. |

| 25. | Kato M, Imamura M, Hosotani R, Shimada Y, Doi R, Itami A, Komoto I, KosakaM T T, Konishi J. Curative resection of microgastrinomas based on the intraoperative secretin test. World J Surg. 2000;24:1425-1430. |

| 26. | Turner JJ, Wren AM, Jackson JE, Thakker RV, Meeran K. Localization of gastrinomas by selective intra-arterial calcium injection. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;57:821-825. |

| 27. | Gibril F, Venzon DJ, Ojeaburu JV, Bashir S, Jensen RT. Prospective study of the natural history of gastrinoma in patients with MEN1: definition of an aggressive and a nonaggressive form. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5282-5293. |

| 28. | Goudet P, Murat A, Binquet C, Cardot-Bauters C, Costa A, Ruszniewski P, Niccoli P, Ménégaux F, Chabrier G, Borson-Chazot F. Risk factors and causes of death in MEN1 disease. A GTE (Groupe d'Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) cohort study among 758 patients. World J Surg. 2010;34:249-255. |

| 29. | Klöppel G, Anlauf M, Perren A. Endocrine precursor lesions of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18:150-155. |

| 30. | Bilimoria KY, Talamonti MS, Tomlinson JS, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY, Bentrem DJ. Prognostic score predicting survival after resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of 3851 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:490-500. |

| 31. | Mullen JT, Wang H, Yao JC, Lee JH, Perrier ND, Pisters PW, Lee JE, Evans DB. Carcinoid tumors of the duodenum. Surgery. 2005;138:971-977; discussion 977-978. |

| 32. | Zyromski NJ, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Thompson GB, Farley DR, Sarr MG. Duodenal carcinoid tumors: how aggressive should we be? J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:588-593. |

| 33. | Anlauf M, Garbrecht N, Henopp T, Schmitt A, Schlenger R, Raffel A, Krausch M, Gimm O, Eisenberger CF, Knoefel WT. Sporadic versus hereditary gastrinomas of the duodenum and pancreas: distinct clinico-pathological and epidemiological features. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5440-5446. |