Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1286

Revised: December 16, 2010

Accepted: December 23, 2010

Published online: March 14, 2011

AIM: To assess the efficacy and tolerability of thalidomide in pediatric Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: Six patients with refractory CD received thalidomide at an initial dose of 2 mg/kg per day for one month, then increased to 3 mg/kg per day or decreased to 1 mg/kg per day, and again further reduced to 0.5 mg/kg per day, according to the individual patient’s response to the drug.

RESULTS: Remission was achieved within three months. Dramatic clinical improvement was demonstrated after thalidomide treatment. Endoscopic and pathological improvements were also observed after thalidomide treatment, which was well tolerated by all patients.

CONCLUSION: Thalidomide is a useful drug for pediatric refractory CD.

- Citation: Zheng CF, Xu JH, Huang Y, Leung YK. Treatment of pediatric refractory Crohn’s disease with thalidomide. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1286-1291

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1286.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1286

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic transmural inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may involve any part of the alimentary tract from mouth to anus, especially the distal ileum and colon. It may also accompany various intra- and extra-intestinal complications during its clinical course[1,2]. In addition to causing serious clinical symptoms and complications, its chronic nature can adversely affect the quality of life of patients[3,4]. Despite an increasing number of treatment options, many patients with CD continue to pose a therapeutic challenge because they do not adequately respond to therapy, or because they experience serious side effects of standard medical interventions. This is particularly true for those patients with refractory CD or concomitant tuberculosis. There is an urgent need to develop new treatment modalities for refractory CD.

Thalidomide, originally used to treat morning sickness in the early 1960s, has been withdrawn from the market because it leads to serious congenital birth defects. In 1991, it was discovered that thalidomide can inhibit the synthesis of cytokine, a tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), by accelerating the degradation of its mRNA[5]. Interest in thalidomide has intensified in recent years since its immunomodulatory[6,7] and anti-angiogenic[8,9] properties were identified and clarified. A series of clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of thalidomide in treatment of several clinical conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated wasting syndrome[10], hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia[11], refractory cutaneous lesions of lupus erythematosus[12], multiple myeloma[13], and Behcet’s disease[14], for which there are few or no alternative treatment options. Based on these observed clinical responses and the apparent anti-TNF-α properties of thalidomide, we used it in treatment of a 12-year-old boy with concomitant refractory CD and tuberculosis infection, and achieved a dramatic success. With this experience, we started to treat refractory CD with thalidomide. Following is a report of 6 children with a complete remission after treated with thalidomide.

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital of Fudan University and informed consent was obtained from all patients and their parents.

This is a retrospective study of 6 patients with refractory CD who visited the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in 2006-2010 (Table 1). Conventional therapy failed in these patients, and/or they could not receive steroid or immunosuppressive treatment because of concomitant tuberculosis infection.

| Patients | ||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| Gender | M | M | M | F | M | F |

| Current age | 20 | 13 | 12 | 16 | 9 | 13 |

| Age at onset (yr) | 12 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 5 | 11 |

| Duration of disease (yr) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Thalidomide start age (yr) | 16 | 12 | 12 | 16 | 9 | 13 |

| Duration of thalidomide treatment (mo) | 12 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 |

| Start dose (mg/kg per day) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Dose at sixth months (mg/kg per day) | 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 |

| PCDAI score before thalidomide treatment | 55 | 67.5 | 70 | 65 | 72.5 | 65 |

| PCDAI score after six months of thalidomide treatment | 5 | 5 | 7.5 | 5 | 5 | 12.5 |

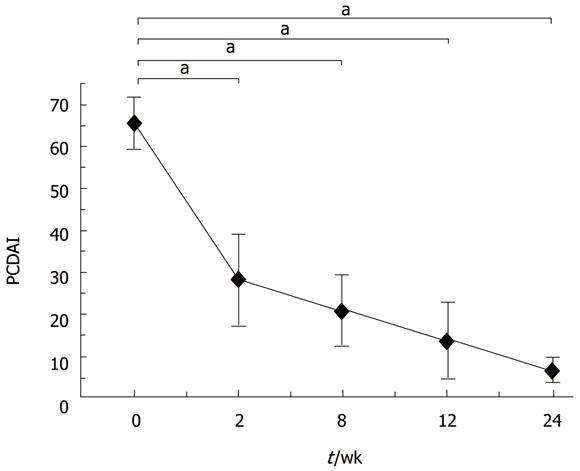

Patients administered thalidomide in the evening at a starting dose of 2.0 mg/kg per day, which was increased to 2.5-3.0 mg/kg per day or decreased to 1.5 mg/kg per day, according to the individual patient’s response to the drug. Patients were assessed at baseline, at weeks 2, 8 and 12, and then every three months for the following parameters, including physical examination, laboratory analyses and pediatric CD activity index (PCDAI) scoring. Endoscopies were repeated at six months after administration of thalidomide. Its side effects were intensely monitored during follow-up. CD was defined as refractory when standard induction therapy with high-dose intravenous steroids failed to induce remission either at diagnosis or during subsequent relapse. Efficacy was defined as thalidomide induced and maintained remission and mean time to achieve clinical remission (PCDAI[15] < 7.5).

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Changes in interval PCDAI scores were evaluated by multivariate analysis of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

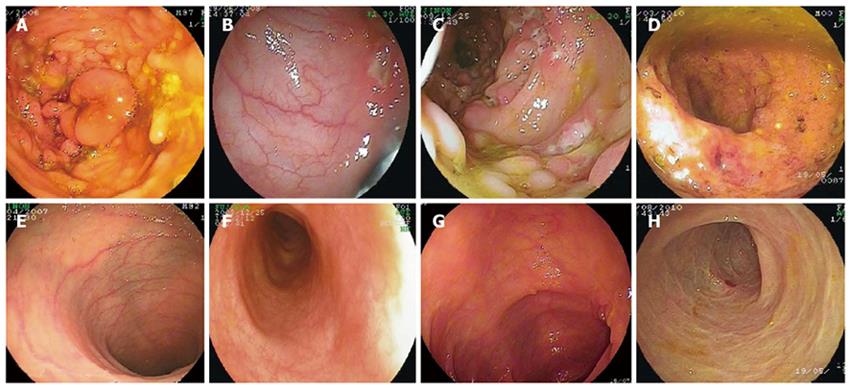

Patient A was a 22-year-old boy with a 10-year history of CD. Steroids and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) were administered for 4 years. However, abdominal pain, diarrhea and fever were still recurrent, and the patient remained seriously undergrown: 42.5 kg, below 10th percentile (< P10) weight-for-age and 162 cm (< P10 height-for-age). In 2006, an immunosuppressant, azathioprine, was started but could not be tolerated because of severe thrombocytopenia. He was then given thalidomide (2 mg/kg per day) in addition to prednisone (10 mg/d) and 5-ASA for four weeks, after which the dosage of steroid was reduced gradually while that of thalidomide was increased. After eight weeks of thalidomide treatment, abdominal pain and fever improved significantly, and the dosage of thalidomide was increased to 3 mg/kg per day while the dose of prednisone was reduced to 5 mg/d. After six months of treatment, this patient achieved complete clinical remission. The dose of thalidomide was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg per day and prednisone was withdrawn. Enteroscopic examination at this time showed that the mucosal ulceration and hyperplasia improved significantly. During thalidomide therapy, this patient experienced transient hepatic function abnormality which became normal after withdrawal of thalidomide. In August 2010, both thalidomide and prednisone were withdrawn and he was on 5-ASA for maintenance of remission without any clinical evidence for recurrence of the disease. His body weight was 67 kg (P75-P90, weight-for-age) and height was 168 cm (P10-P25, height-for-age).

Patient B, a 13-year-old boy with a 5-year history of splenic tuberculosis, was diagnosed as CD 3 years ago. This patient also had a history of chronic diarrhea accompanying hematochezia, abdominal pain, weight loss, oral and perianal ulcers, anemia, fatigue, malnutrition and spiking fever up to 40°C. Symptoms did not improve upon anti-tuberculosis (TB) treatment with rifampin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide, and splenectomy was performed 3 years ago after which the symptoms persisted. In June 2009, double-balloon enteroscopy demonstrated segmental distribution of ulcers with different sizes and characteristics in the colon and ileum. Histological examination revealed acute and chronic mucosal inflammation and hyperplasia, with infiltration of a large number of neutrophils, plasma cells, macrophages and scanty eosinophils. Bone marrow culture identified Mycobacterium. Steroids, immunosuppressive agents and biologics such as infliximab could not be used due to concurrent tuberculosis infection, thalidomide was therefore chosen as the second-line therapy for his CD.

After he received thalidomide at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day for two weeks, his body temperature returned to normal, his abdominal pain and diarrhea were significantly alleviated, and his oral ulcers became more superficial and then completely disappeared. After one month of treatment, steroids were withdrawn. Six months later, thalidomide was reduced to 0.5 mg/kg per day. His body weight increased from 33 kg (< P10, weight-for-age) to 54 kg (P50-P75, weight-for-age). Endoscopic examination revealed that the intestine appeared almost normal, and laboratory data improved significantly with a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). In August 2010, he was on thalidomide, 1.0 mg/kg per day, to maintain remission. No adverse effect was found throughout the treatment.

Patient C was an 11-year-old boy who underwent two surgical procedures for perianal abscess in September 2008 and February 2009 and had a positive history of close contact with a TB patient. TB-PPD test was strongly positive, but culture of intestinal mucosa for tuberculosis was negative. He had no response to 5-ASA and a limited response to immunosuppressive agents. In November 2009, colonoscopy identified several polyps and ulcers in the transverse and ascending colon. Because of suspected Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, steroid was not used in this patient. Treatment with thalidomide at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day was started in November 2009. After two weeks of thalidomide treatment, his symptoms including fever, abdominal pain and diarrhea were significantly relieved. CRP and ESR became normal within two months after thalidomide treatment, and his body weight increased from 27 kg (< P10, weight-for-age) to 37.5 kg (P20-P50, weight-for-age). After six months of thalidomide treatment, the PCDAI was reduced to 7.5 from 70 before thalidomide treatment.

Patient D, a 16-year-old girl with a 5-year history of CD, suffered from severe abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea and severe malnutrition. Growth failure was very marked in this patient. Her body weight was only 21 kg (< P10, weight-for-age) while her height was 130 cm (< P10, height-for-age) when she was 15 years old, and showed no secondary sexual characteristics. During the five years of treatment with steroids, immunosuppressive agents and 5-ASA, her clinical symptoms were relieved significantly, but her height or weight did not increase after the diagnosis of CD. In April 2010, thalidomide therapy was initiated. Three months after treatment, her appetite was significantly improved, her body weight increased from 21 to 33 kg (< P10, weight-for-age) and her height increased 1 cm.

Patient E was a 9-year-old boy with a four-year history of CD accompanying recurrent fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea and poor weight gain. PPD test was regarded as positive when the induration was 18 mm × 18 mm. He was diagnosed with intestinal tuberculosis and received anti-TB therapy for one year without any improvement in his symptoms. Because he was allergic to a variety of foods including egg, milk, soybean, peanut and wheat, his allergic colitis was treated by failed. During the last two years, he developed edema in lower limbs, ascites and pleural effusion attributable to serious malnutrition. In 2009, colonoscopy showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and segmental distribution of ulcers in the colon and terminal ileum, and CD was diagnosed. Infliximab was contraindicated in this patient because of the positive tuberculin test, thalidomide was therefore given to control his CD. After three months of treatment, the both CRP and ESR decreased significantly. His symptoms also improved quite remarkably.

Patient F was a 13-year-old girl with a 2-year history of CD accompanying abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea and hematochezia. The patient received steroid treatment during the last two years and clinical symptoms were relieved significantly. However, when the dose of steroids was reduced gradually, her clinical symptoms appeared again. She became steroid-dependent with obvious cushingoid features developed last year. Based on the strong desire of the patient and her parents, thalidomide treatment was started at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day in April 2010. After three months of thalidomide treatment, steroids were withdrawn and her clinical symptoms improved significantly.

In conclusion, thalidomide is an effective treatment modality for refractory CD. However, its long-term efficacy and safety need to be further evaluated in a large-scale randomized controlled trial (Figures 1 and 2).

TNF-α, one of the most important immunologic mediators generated by cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage, has a broad spectrum of biological functions and plays a crucial role in amplification of responses to infection, injury, and immune-mediated damage. As a cytokine, TNF-α can transmit signals between immune and other cells, and is involved in apoptosis, metabolism, inflammation, thrombosis, and fibrinolysis[16]. The importance of TNF-α and TNF-α signaling in response of the immune system to disease has become clearer as a result of a number of seminal studies[17-19]. It was reported that mice lacking of TNF-α show a high susceptibility to infectious agents[17] and also an impaired clearance of adenoviral vectors[18]. In addition, gene knockout experiments (TNF-α--/- mice) showed that TNF-α is necessary for adhesion molecule expression and recruitment of leukocytes to inflammatory sites[19].

Although TNF-α has critical physiological functions, its overproduction plays a key role in physiopathology of a variety of diseases. Of relevance to IBD are the abilities of TNF-α to recruit circulating inflammatory cells to local tissue sites of inflammation, to induce edema, to activate coagulation cascade, and to initiate formation of granuloma[20]. Clinical trials demonstrating symptomatic improvement and remission of CD by suppressing TNF-α have provided additional evidence of the role of TNF-α in pathogenesis of CD[21-24].

Thalidomide was developed in the 1960s as a sedative but was subsequently withdrawn from widespread use because of teratogenicity. The drug has been banned for more than two decades when it was shown to inhibit TNF-α production[5], thus leading to its revival in clinical settings. This property of thalidomide was first described in treatment of patients with systemic erythema nodosum leprosum[25]. Such patients demonstrated an extremely high TNF-α level in their blood, which decreased significantly during thalidomide treatment, indicating that thalidomide therapy can reduce not only serum TNF-α level, but also clinical symptoms as well. Dermal infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and T cells are also diminished after treatment with thalidomide[25]. Studies also demonstrated that thalidomide improves clinical symptoms in patients with HIV-associated wasting syndrome[10], multiple myeloma[13], Behcet’s disease[14] and CD[26-30]. Suppression of TNF-α may be the mechanism underlying CD. It was reported that thalidomide treatment can restore the normal levels myeloperoxidase and TNF-α in a rat model of IBD[27].

Tuberculosis is still quite common in China. Treatment of CD patients with simultaneous TB infection may be difficult. In this situation, administration of steroids or immunosuppressive agents may lead to reactivation of latent tuberculosis or its flare-up. In this study, thalidomide was a good choice for such patients, which not only improved the symptoms of CD, but also enhanced the response of the patients to anti-TB drugs.

Although thalidomide can more uniquely improve the symptoms of many diseases than other drugs, it may lead to significant problems due to its side-effects. The most serious side-effect is teratogenicity. Moreover, thalidomide often has other side-effects, including peripheral neuropathy. For these reasons, synthetic thalidomide analogues (IMiDs) with an increased TNF-α inhibitory activity and diminished side effects are desirable. Many analogues exhibit a higher inhibition of TNF-α expression than thalidomide. In particular, the IMiDs, lenalidomide and pomalidomide (CC-4047), are respectively 2000- and 20 000-fold more potent than thalidomide in inhibiting TNF-α and able to induce transcription and secretion of TGF-β and IL-10[31]. The 4-amino analogues (in which an amino group is added to the fourth carbon of the phthaloyl ring of thalidomide) have been found to be up to 50 000-fold more potent in inhibiting TNF-α than thalidomide in vitro[32]. Several of these new compounds in vivo are able to reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α levels in mice[33] and inhibit development of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats[34]. Whether IMiDs have a greater therapeutic efficacy with fewer side-effects than thalidomide needs to be determined. It was reported that neuropathy may occur only after high cumulative doses of thalidomide are used[26,29], indicating that thalidomide can be used as a maintenance modality.

Despite an increasing number of treatment options, treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) is still a challenge of physicians due to its poor response to therapy or serious side effects of standard medical interventions. This is particularly true for those with refractory Crohn’s disease or concomitant tuberculosis infection. Thalidomide, a synthetic glutamic acid derivative, has anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties. Studies suggest that thalidomide can significantly inhibit the synthesis of a tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and plays a role in up-regulation of Th2-type immunity. Thalidomide may be a good choice for Crohn’s disease patients.

Treatment of CD patients with tuberculosis infection may be difficult. In this situation, administration of steroids or immunosuppressive agents may lead to reactivation of latent tuberculosis or tuberculosis infection flare-up, but tuberculosis infection is still quite common in some countries including China. It is therefore urgent to develop new treatment modalities for such patients.

Therapy for refractory Crohn’s disease or concomitant tuberculosis infection is always a challenge. In the present study, thalidomide was a good choice for such patients, which can not only improve the symptoms of CD, but also enhance the response of the patients to anti- tuberculosis drugs. CD patients tolerate it quite well.

This study may offer a future strategy for therapeutic intervention of CD patients with a poor response to therapy or serious side effects of standard medical interventions.

Refractory Crohn’s disease refers to a condition in which standard induction therapy iwith high-dose intravenous steroids has failed to induce remission either at diagnosis or during subsequent relapse. Pediatric CD activity index is a rating scale used to assess the severity of pediatric Crohn’s disease and correlates well with disease activity.

Although the number of patients investigated was small, the study was interesting, and well written. This manuscript is acceptable as a short article in WJG.

Peer reviewer: Takayuki Yamamoto, MD, PhD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Yokkaichi Social Insurance Hospital, 10-8 Hazuyamacho, Yokkaichi, Mie 510-0016, Japan

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Maeda K, Okada M, Yao T, Sakurai T, Iida M, Fuchigami T, Yoshinaga K, Imamura K, Okada Y, Sakamoto K. Intestinal and extraintestinal complications of Crohn’s disease: predictors and cumulative probability of complications. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:577-582. |

| 2. | Rothfuss KS, Stange EF, Herrlinger KR. Extraintestinal manifestations and complications in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4819-4831. |

| 3. | Gabalec L, Bures J, Sedová M, Valenta Z. [Quality of life of Crohn’s disease patients]. Cas Lek Cesk. 2009;148:201-205. |

| 4. | Cohen RD. The quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1603-1609. |

| 5. | Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, Cohn ZA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:699-703. |

| 6. | Corral LG, Kaplan G. Immunomodulation by thalidomide and thalidomide analogues. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58 Suppl 1:I107-I113. |

| 7. | Dredge K, Marriott JB, Dalgleish AG. Immunological effects of thalidomide and its chemical and functional analogs. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22:425-437. |

| 8. | D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4082-4085. |

| 9. | Dredge K, Marriott JB, Macdonald CD, Man HW, Chen R, Muller GW, Stirling D, Dalgleish AG. Novel thalidomide analogues display anti-angiogenic activity independently of immunomodulatory effects. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1166-1172. |

| 10. | Kaplan G, Thomas S, Fierer DS, Mulligan K, Haslett PA, Fessel WJ, Smith LG, Kook KA, Stirling D, Schambelan M. Thalidomide for the treatment of AIDS-associated wasting. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:1345-1355. |

| 11. | Lebrin F, Srun S, Raymond K, Martin S, van den Brink S, Freitas C, Bréant C, Mathivet T, Larrivée B, Thomas JL. Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2010;16:420-428. |

| 12. | Coelho A, Souto MI, Cardoso CR, Salgado DR, Schmal TR, Waddington Cruz M, de Souza Papi JA. Long-term thalidomide use in refractory cutaneous lesions of lupus erythematosus: a 65 series of Brazilian patients. Lupus. 2005;14:434-439. |

| 13. | van de Donk NW, Kröger N, Hegenbart U, Corradini P, San Miguel JF, Goldschmidt H, Perez-Simon JA, Zijlmans M, Raymakers RA, Montefusco V. Remarkable activity of novel agents bortezomib and thalidomide in patients not responding to donor lymphocyte infusions following nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:3415-3416. |

| 14. | Direskeneli H, Ergun T, Yavuz S, Hamuryudan V, Eksioglu-Demiralp E. Thalidomide has both anti-inflammatory and regulatory effects in Behcet’s disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:373-375. |

| 15. | Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, Gryboski JD, Kibort PM, Kirschner BS, Griffiths AM, Katz AJ, Grand RJ, Boyle JT. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:439-447. |

| 16. | McDermott MF. TNF and TNFR biology in health and disease. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand. ). 2001;47:619-635. |

| 17. | Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397-1411. |

| 18. | Marino MW, Dunn A, Grail D, Inglese M, Noguchi Y, Richards E, Jungbluth A, Wada H, Moore M, Williamson B. Characterization of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8093-8098. |

| 19. | Wada H, Saito K, Kanda T, Kobayashi I, Fujii H, Fujigaki S, Maekawa N, Takatsu H, Fujiwara H, Sekikawa K. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) plays a protective role in acute viralmyocarditis in mice: A study using mice lacking TNF-alpha. Circulation. 2001;103:743-749. |

| 21. | van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Bijl HA, Jansen J, Tytgat GN, Woody J. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2). Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129-135. |

| 22. | Oussalah A, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Efficacy of TNF antagonists beyond one year in adult and pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:156-175. |

| 23. | Bell S, Kamm MA. Antibodies to tumour necrosis factor alpha as treatment for Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2000;355:858-860. |

| 24. | Nakamura K, Honda K, Mizutani T, Akiho H, Harada N. Novel strategies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: Selective inhibition of cytokines and adhesion molecules. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4628-4635. |

| 25. | Sampaio EP, Kaplan G, Miranda A, Nery JA, Miguel CP, Viana SM, Sarno EN. The influence of thalidomide on the clinical and immunologic manifestation of erythema nodosum leprosum. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:408-414. |

| 26. | Bauditz J, Wedel S, Lochs H. Thalidomide reduces tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 12 production in patients with chronic active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2002;50:196-200. |

| 27. | Prakash O, Medhi B, Saikia UN, Pandhi P. Effect of different doses of thalidomide in experimentally induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103:9-16. |

| 28. | Ehrenpreis ED, Kane SV, Cohen LB, Cohen RD, Hanauer SB. Thalidomide therapy for patients with refractory Crohn’s disease: an open-label trial. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1271-1277. |

| 29. | Casella G, De Marco E, Monti C, Baldini V. The therapeutic role of thalidomide in inflammatory bowel disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2006;52:293-301. |

| 30. | Lazzerini M, Martelossi S, Marchetti F, Scabar A, Bradaschia F, Ronfani L, Ventura A. Efficacy and safety of thalidomide in children and young adults with intractable inflammatory bowel disease: long-term results. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:419-427. |

| 31. | De Sanctis JB, Mijares M, Suárez A, Compagnone R, Garmendia J, Moreno D, Salazar-Bookaman M. Pharmacological properties of thalidomide and its analogues. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2010;4:144-148. |

| 32. | Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:314-322. |

| 33. | Corral LG, Muller GW, Moreira AL, Chen Y, Wu M, Stirling D, Kaplan G. Selection of novel analogs of thalidomide with enhanced tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitory activity. Mol Med. 1996;2:506-515. |

| 34. | Oliver SJ, Freeman SL, Corral LG, Ocampo CJ, Kaplan G. Thalidomide analogue CC1069 inhibits development of rat adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:315-321. |