Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1237

Revised: December 22, 2010

Accepted: December 29, 2010

Published online: March 14, 2011

Ascites is one of the major complications of liver cirrhosis and is associated with a poor prognosis. It is important to distinguish noncirrhotic from cirrhotic causes of ascites to guide therapy in patients with noncirrhotic ascites. Mild to moderate ascites is treated by salt restriction and diuretic therapy. The diuretic of choice is spironolactone. A combination treatment with furosemide might be necessary in patients who do not respond to spironolactone alone. Tense ascites is treated by paracentesis, followed by albumin infusion and diuretic therapy. Treatment options for refractory ascites include repeated paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement in patients with a preserved liver function. Potential complications of ascites are spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). SBP is diagnosed by an ascitic neutrophil count > 250 cells/mm3 and is treated with antibiotics. Patients who survive a first episode of SBP or with a low protein concentration in the ascitic fluid require an antibiotic prophylaxis. The prognosis of untreated HRS type 1 is grave. Treatment consists of a combination of terlipressin and albumin. Hemodialysis might serve in selected patients as a bridging therapy to liver transplantation. Liver transplantation should be considered in all patients with ascites and liver cirrhosis.

- Citation: Biecker E. Diagnosis and therapy of ascites in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1237-1248

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1237.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1237

Ascites is one of the major complications of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Within 10 years of the diagnosis of cirrhosis, more than 50% of patients develop ascites[1]. The development of ascites is associated with a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 15% at one-year and 44% at five-year follow-up, respectively[2]. Therefore, patients with ascites should be considered for liver transplantation, preferably before the development of renal dysfunction[1]. This article will give a concise overview of the diagnosis and treatment of patients with ascites in liver cirrhosis and the management of the most common complications of ascites.

Since 15% of patients with liver cirrhosis develop ascites of non-hepatic origin, the cause of new-onset ascites has to be evaluated in all patients[3]. The most important diagnostic measure is diagnostic abdominal paracentesis. Paracentesis is considered a safe procedure even in patients with an abnormal prothrombin time, with an overall complication rate of not more than 1%[4]. More serious complications such as bowel perforation or bleeding into the abdominal cavity occur in less than one in 1000 paracenteses[5]. Data supporting cut-off values for coagulation parameters are not available[6]. One study which included 1100 large-volume paracenteses did not show hemorrhagic complications despite platelet counts as low as 19 g/L and international normalized ratios as high as 8.7[7]. The routine prophylactic use of fresh frozen plasma or platelets before paracentesis is therefore not recommended[6].

Ascitic fluid analysis should include total protein concentration, a neutrophil count and inoculation of ascites into blood culture bottles at the bedside. Determination of ascitic protein concentration is necessary to identify patients who are at increased risk for the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), since a protein concentration below 1.5 g/dL is a risk factor for the development of SBP[8]. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is defined as an ascitic neutrophil count of more than 0.25 g/L (see “treatment of SBP”) and inoculation of ascitic fluid in blood culture flasks at the bedside helps to detect bacteria in the ascitic fluid[9]. Additional test are only necessary in patients in whom other causes of ascites are in the differential diagnosis[10].

In patients in whom a cause of ascites different from liver cirrhosis is suspected, the determination of the serum-ascites-albumin gradient (SAAG) is useful. The SAAG is ≥ 1.1 g/dL in ascites due to portal hypertension with an accuracy of 97%[11].

Uncomplicated ascites is defined as the absence of complications including refractory ascites, SBP, marked hyponatremia or hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)[10].

There are no defined criteria as to when treatment of ascites should be initiated. Patients with clinically inapparent ascites usually do not require a specific therapy. It is recommended that patients with clinically evident and symptomatic ascites should be treated.

In patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, the most important measure is alcohol abstinence. In the majority of patients with alcoholic liver disease, alcohol abstinence results in an improvement of liver function and ascites[12]. Also, decompensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis B infection or autoimmune hepatitis often shows a marked improvement in response to antiviral or immunosuppressive treatment, respectively[13].

Patients with uncomplicated mild or moderate ascites do not require hospitalization and can be treated as outpatients. Patients with ascites have a positive sodium balance, i.e. sodium excretion is low relative to sodium intake. Hence, the mainstay of ascites therapy is sodium restriction and diuretic therapy. Sodium intake should be restricted to 5-6 g/d (83-100 mmol/d NaCl)[14-16]. A more stringent restriction is not recommended since this diet is distasteful and may worsen the malnutrition that is often present in patients with liver cirrhosis[16]. A French study showed that a more stringent sodium restriction of 21 mmol/d led to a faster mobilization of ascites in the first 14 d, but revealed no difference after 90 d[17]. Another study found no benefit in patients treated with a strict sodium restriction of 50 mmol/d compared to patients with a moderate sodium restriction of 120 mmol/d[18].

Theoretically, upright posture aggravates sodium retention by an increase of plasma renin activity and has led to the recommendation of bed rest. However, there are no clinical studies that provide evidence that bed rest actually improves ascites[6].

Therapy of ascites that is based solely on sodium restriction is only applicable in patients with a 24 h sodium excretion of more than 80 mmol (90 mmol dietary intake - 10 mmol loss by sweat and feces) since an adequate sodium excretion is the requirement for a negative sodium balance. Patients with a 24 h sodium excretion less than 80 mmol/24 h need diuretic therapy.

Hyponatremia is a common finding in patients with ascites and liver cirrhosis, but a study including 997 patients with liver cirrhosis found severe hyponatremia (≤125 mmol/L) in only 6.9% of patients[19]. Another study, including 753 patients evaluated for liver transplantation, found hyponatremia of less than 130 mmol/L in 8% of patients and an increase in the risk of death as sodium decreased to between 135 and 120 mmol/L[20]. Since the total body sodium is not decreased in patients with ascites and hyponatremia (dilution hyponatremia), rapid correction of serum sodium is not indicated but has the risk of severe complications[21]. Fluid restriction is recommended in patients with severe hyponatremia (120-125 mmol/L)[6], but clinical studies that have evaluated the efficacy of fluid restriction, or the extent of hyponatremia when fluid restriction should be initiated, are lacking.

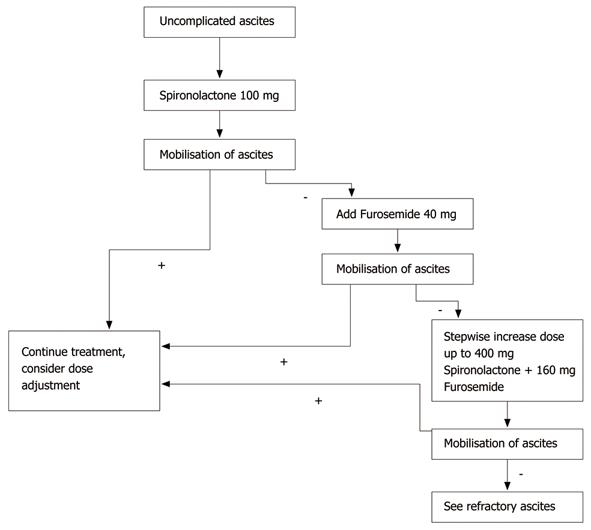

The activation of the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin-system in patients with liver cirrhosis causes hyperaldosteronism and increased reabsorption of sodium along the distal tubule[22]. Therefore, aldosterone antagonists like spironolactone or its active metabolite potassium canrenoate are considered the diuretics of choice[23]. Patients with mild to moderate ascites are treated with a monotherapy of spironolactone. The starting dose is 100-200 mg/d[24]. A monotherapy with a loop diuretic like furosemide is less effective compared to spironolactone and is not recommended[23]. If the response to 200 mg spironolactone within the first two weeks is not sufficient, furosemide with an initial dose of 20-40 mg/d is added. If necessary, the spironolactone dose is increased stepwise up to 400 mg/d and the furosemide dose is increased up to 160 mg/d[22,23,25].

The daily weight loss in patients with or without peripheral edema should not exceed 1000 g or 500 g, respectively[26]. A sufficient diuretic effect is achieved when only small amounts of ascites are left and peripheral edema has completely resolved.

It is generally recommended to apply furosemide orally, since intravenous administration bears the risk of azotemia[27,28]. A combination therapy of spironolactone and furosemide shortens the response time to diuretic therapy and minimizes adverse effects such as hyperkalemia[29]. Angeli and co-workers compared the sequential therapy with potassium canrenoate and furosemide with the initial combination therapy of these two drugs[30]. Patients receiving the sequential therapy were treated with an initial dose of 200 mg potassium canrenoate that was increased to 400 mg/d. Non-responders to the initial therapy were treated with 400 mg/d of potassium canrenoate and furosemide at an initial dose of 50 mg/d that was increased to 150 mg/d. Patients receiving the combination therapy were treated with an initial dose of 200 mg/d potassium canrenoate and 50 mg of furosemide that was increased to 400 mg/d and 150 mg/d, respectively. A sufficient treatment response was achieved in both treatment groups. However, there were more adverse effects of diuretic treatment (e.g. hyperkalemia) in the patients receiving the sequential therapy. In contrast to this study, another study found no difference comparing sequential and combination therapy[31]. Possible explanations for these conflicting results are the different patient populations included in the studies. Angeli et al[30] included patients with recidivant ascites and reduction in the glomerular filtration rate whereas in the study of Santos et al[31], the majority of patients had newly diagnosed ascites.

An established scheme for an initial combination therapy is 100 mg spironolactone and 40 mg furosemide per day given in the morning[32]. If this dosage is not sufficient, a stepwise increase keeping the spironolactone/furosemide ratio (e.g. 200 mg spironolactone/80 mg furosemide) is possible. The combination of spironolactone and furosemide lowers the risk of a spironolactone-induced hyperkalemia.

The combination of sodium restriction, spironolactone and furosemide achieves a sufficient therapy of ascites in patients with liver cirrhosis in 90% of cases[18,23,25]. Figure 1 shows an algorithm for the diuretic treatment of patients with uncomplicated ascites.

Several studies have evaluated the newer loop-diuretic torasemide in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites[33-35]. Torasemide was shown to be at least as effective and safe as furosemide and is considered an alternative in the treatment of ascites[33-35].

Amiloride is an alternative to spironolactone in patients with painful gynecomastia. Amiloride is given in a dose of 10-40 mg/d but is less effective than potassium canrenoate[36].

Complications of diuretic therapy include hepatic encephalopathy, renal failure, gynecomastia, electrolyte disturbances such as hyponatremia, hypo- or hyperkalemia, as well as muscle cramps[22,23,30,31,36]. To minimize these complications, it is generally advised to reduce the dosage of diuretic drugs after the mobilization of ascites. Complications of diuretic therapy are most frequent in the first weeks after initiation of therapy[30].

A common complication of diuretic therapy is hyponatremia. The level of hyponatremia at which diuretic treatment should be stopped is a subject of discussion. It is generally agreed that diuretics should be paused when the serum sodium is less than 120-125 mmol/L[6].

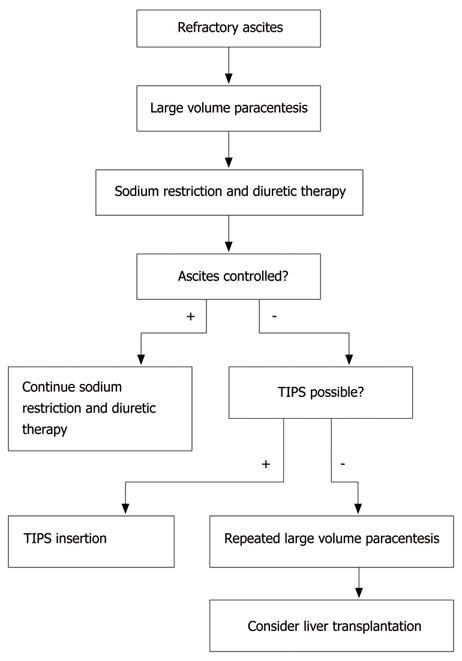

Refractory ascites is defined as ascites that does not respond to sodium restriction and high-dose diuretic treatment (400 mg/d spironolactone and 160 mg/d furosemide) or that reoccurs rapidly after therapeutic paracentesis[3]. About 10% of patients with cirrhosis and ascites are considered to have refractory ascites[6]. The median survival of patients with ascites refractory to medical treatment is approximately six months[3,37-39].

Possible treatment options for refractory ascites include large volume paracentesis (LVP), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and liver transplantation.

Large volume paracentesis is the treatment of choice for patients with tense ascites. It is considered a safe procedure[40] and complication rates are not higher than in diagnostic paracentesis[4,7]. The risk of bleeding is generally low and a relationship between the degree of coagulopathy and the risk of bleeding is not evident[40]. Hence, there are no data that support the prophylactic administration of pooled platelets and/or fresh frozen plasma prior to paracentesis. Nevertheless, in patients with severe coagulopathy, paracentesis should be performed with caution. Paracentesis is performed under sterile conditions. If ultrasound is available, it should be used to localize the best puncture site to minimize the risk of bowel perforation.

The most important complication following LVP is paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction (PICD)[41-43]. This is caused by a depletion of the effective central blood volume leading to a further stimulation of vasoconstrictor systems. Post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction is characterized by a deterioration of renal function that can ultimately culminate in hepatorenal syndrome in up to 20% of patients[42]. A rapid re-accumulation of ascites[44], hyponatremia, as well as an increase in portal pressure[45], are additional consequences. PICD is associated with an increase in mortality[41].

Paracentesis of not more than 5 L can safely be conducted without post-paracentesis colloid infusions and the risk of PICD[46]. If a paracentesis of more than 5 L is performed, the administration of albumin is advisable[47]. However, it has to be kept in mind that albumin is costly, and that studies that are large enough to demonstrate decreased survival in patients who are given no plasma expander compared to patients given albumin are lacking[41]. There are no studies that have evaluated the appropriate dose of albumin after paracentesis. In the available studies, 5 to 10 g of albumin per litre of removed ascites have been given[41,42,47,48]. Hence, a dose of 6-8 g albumin per litre of removed ascites seems appropriate[6]. Dextran-70 and polygeline as alternative plasma expanders have been compared to albumin for the prevention of PICD after LVP but have been shown to be less effective[41]. However, a benefit in survival in favor of albumin over dextran-70, polygeline and saline was not shown in three trials[41,49,50]. Albumin should be administered slowly after the completion of paracentesis to reduce the risk of a volume overload.

Large volume paracentesis per se does not positively influence renal sodium and water retention. To prevent the re-accumulation of ascites after LVP, sodium restriction and diuretic treatment are necessary[51].

TIPS provides a side-to-side porto-caval shunt. It is usually placed under local anesthesia by transhepatic puncture of the (usually) right main branch of the portal vein using an approach from a hepatic vein. After the connection between the hepatic and portal vein is established, the tract is dilated and a stent is placed[52].

Contraindications for TIPS in the therapy of recurrent ascites include advanced liver disease (bilirubin > 5 mg/dL), episodic or persistent hepatic encephalopathy, cardiac or respiratory failure and hepatocellular carcinoma[53-57].

TIPS insertion causes an increase in right atrial and pulmonary artery pressure as well as an increase in cardiac output, a reduction of systemic vascular resistance, a reduction of effective arterial blood volume and, most importantly, a reduction of portal pressure[52,58-67]. Whereas the effect on renal function (increased sodium excretion and increased glomerular filtration rate) persists, the increase in cardiac output tends to return to pre-TIPS levels[59-63,67].

Compared to repeated LVP, TIPS is more effective in the therapy of ascites[53,55,68], but the effect on mortality is less clear. Whereas two studies showed no difference in mortality comparing paracentesis and TIPS[53,57], another two studies revealed decreased mortality in patients receiving TIPS[55,56]. A meta-analysis based on individual patient data from four randomized trials showed that TIPS in patients with refractory ascites improved transplant-free survival[68].

A frequent complication after TIPS insertion is hepatic encephalopathy, which occurs in 30%-50% of patients[69,70], but seems to be less frequent in carefully selected patients with preserved liver function. Other complications are shunt thrombosis and shunt stenosis[69,71]. Shunt thrombosis and shunt stenosis were shown to be less frequent in polytetrafluoroethylene (e-PTFE) coated stents compared to non-coated stents in one study[72]. A retrospective multicenter study showed that the use of e-PTFE covered stents is associated with a higher 2-year survival compared to non-covered stents[73].

Figure 2 shows an algorithm for the treatment of refractory ascites.

The occurrence of renal failure in patients with advanced liver disease in the absence of an identifiable cause of renal failure is defined as hepatorenal syndrome[3]. Therefore, it is essential to rule out other possible causes of renal failure before the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is made. In 1994, the International Ascites Club defined criteria for the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome[3] that were modified in 2007[74]. The modified criteria include: (1) cirrhotic liver disease with ascites; (2) a serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL; (3) no improvement of serum creatinine (decrease to ≤ 1.5 mg/dL) after at least 2 d with diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin (1 g/kg body weight/d up to 100 g/d); (4) absence of shock; (5) no current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs; and (6) absence of parenchymal kidney disease[74]. According to the progression of renal failure, two types of HRS are defined: type 1 is rapidly progressive with a doubling of the initial serum creatinine to > 2.5 mg/dL or a 50% reduction of the initial 24-h creatinine clearance to < 20 mL/min in less than 2 wk. Patients with HRS type 2 do not have a rapidly progressive course[74].

HRS type 1 often develops in temporal relationship with a precipitating factor like infection (e.g. spontaneous bacterial peritonitis)[75-78] or severe alcoholic hepatitis in patients with advanced cirrhosis. The prognosis of all patients with HRS is poor with a median survival of approximately three months[79,80]. The prognosis of patients with untreated HRS type 1 is even worse, with a median survival of only one month[81].

Treatment should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis is made to prevent further deterioration of renal function. Several treatment options of HRS are available: drug therapy, hemodialysis, TIPS and liver transplantation.

Drug therapy of HRS consists of the application of vasopressors in combination with albumin.

One randomized, controlled study compared the effect of noradrenalin as a continuous intravenous infusion in combination with albumin vs terlipressin and albumin in 40 patients with HRS type 1[82]. The study did not reveal a significant difference in short-term survival between the two groups. Two studies demonstrated that treatment with octreotide alone is not successful[83,84] but that a combination with the vasopressor midodrine is required. Two other studies investigated the effect of octreotide and midodrine in combination with albumin[85,86]. One small study compared octreotide 200 μg subcutaneously three times a day, midodrine up to 12.5 mg/d orally and albumin 10-20 g/d with dopamine plus albumin[85]. The results in the octreotide/midodrine group were superior to those in the dopamine group. A larger, retrospective study compared a combination treatment with octreotide/midodrine and albumin with a treatment with albumin only[86]. The mortality rate of the patients treated with the combination of octreotide, midodrine and albumin was lower than the mortality rate of the patients treated with albumin alone (43% vs 71%, respectively). More data are available with regard to the vasoconstrictor terlipressin in the treatment of HRS type 1. Treatment with terlipressin is started with an initial dose of 1 mg 4-6 times a day and is given in combination with albumin (1 g/kg body weight on day 1, followed by 40 g/d)[87]. If a reduction of serum creatinine of at least 25% is not achieved after three days of therapy, the dose is increased to a maximum of 2 mg 4-6 times a day. The treatment is continued until a reduction of serum creatinine below 1.5 mg/dL is achieved. The median response time is around two weeks[88]. Patients with a better liver function and an early increase in arterial pressure after initiation of treatment have a higher probability of treatment response[88]. Treatment with terlipressin is successful in 40%-50% of patients[89,90]. Cardiovascular or ischemic complications are the most important adverse effects of terlipressin treatment[80,89]. A meta-analysis of randomized trials regarding terlipressin and other vasoactive drugs showed an improved short-term survival for the patients treated with terlipressin[90].

Two small studies evaluated the effect of terlipressin in patients with HRS type 2[91,92]. Both studies showed an improvement of renal function with terlipressin treatment[91,92].

TIPS has been shown to improve renal function in HRS type 1 patients in two studies[60,93]. However, the results of these studies might be biased since only patients with a maintained liver function underwent TIPS insertion. In addition, TIPS insertion is beneficial in patients with HRS type 2[53].

Few data are available on the role of hemodialysis in patients with HRS type 1[94,95]. Hemodialysis seems to be effective, but studies comparing hemodialysis with medical treatment or TIPS are lacking. Hence, hemodialysis remains a therapy option in selected patients with electrolyte disturbances, severe acidosis or volume overload and as a bridging therapy in patients awaiting liver transplantation.

The treatment option of choice for patients with HRS type 1 and HRS type 2 is liver transplantation[96]. However, the survival rate of 65% is low compared to other cirrhotic patients who have undergone liver transplantation. In addition, the mortality rate on the waiting list for liver transplantation of patients with HRS is higher than for patients with cirrhosis without HRS. Combined liver-kidney transplantation is usually not necessary. Only patients who have been on hemodialysis for more than 12 wk might be considered for combined liver-kidney transplantation as renal function might irreversibly deteriorate in patients with HRS and long-term hemodialysis[97,98].

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a bacterial infection of the peritoneal cavity in patients with cirrhosis and ascites[99-101]. All patients with cirrhosis and ascites are at risk of developing SBP. Symptoms are often unspecific and include signs of peritonitis, clinical and laboratory signs of inflammation, deterioration of liver function, gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy[102-104]. The prevalence in hospitalized patients is approximately 10% and higher than in outpatients (1.5%-3.5%)[102,103].

The diagnosis of SBP is based on a positive ascitic fluid bacterial culture and an elevated ascitic fluid neutrophil count in patients without an evident source of infection[105]. Ascitic bacterial culture is negative in more than 50% of patients with suspected SBP and an elevated neutrophil count[8,100,101,106]. If bacteria are found in the culture, the most common bacteria include E. coli as well as streptococcus species and enterococci[99-101,106].

A neutrophil count of more than 250 cells/mm3 (0.25 × 109/L) is considered diagnostic of SBP[107]. An ascitic neutrophil count ≥ 250 cells/mm3 but with negative cultures is termed as culture-negative neutrocytic ascites. Several studies were undertaken to investigate the use of reagent strips (“dipstick testing”) designed for the use in urine in the diagnosis of SBP. However, a review of studies comparing different types of reagent strips with cytobacteriological methods revealed a high rate of false negative results for the reagent strips[108].

Patients with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count ≥ 250 cells/mm3 and clinical signs of SBP should receive antibiotic treatment. Also, cirrhotic patients with ascites and signs or symptoms of infection or unexplained clinical deterioration should receive treatment regardless of a neutrophil count below 250 cells/mm3, since it is known that bactericides (positive ascitic fluid culture with a neutrophil count below 250 cells/mm3) might precede the neutrophil response[109].

Treatment should be initiated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic as long as results of bacterial culture are not available. The treatment of choice is a third-generation cephalosporin. Most data are available for cefotaxime. Cefotaxime covers 95% of the causative bacteria including the most common isolates E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and pneumococci[110]. In addition, it reaches high concentrations in the ascitic fluid[110,111]. In most patients, 5 d of treatment is as effective as 10 d of treatment[112]. Ceftriaxone was also shown to be effective in the treatment of SBP and is an alternative to cefotaxime[113]. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, given as a sequential intravenous/oral therapy was shown to be as effective as cefotaxime in a small study[114]. Intravenous ciprofloxacin is similarly effective with respect to survival and SBP resolution rate as treatment with cefotaxime, but costs are higher[115]. In uncomplicated SBP, oral ofloxacin was shown to be as effective as cefotaxime[116]. Since patients who have received quinolone prophylaxis against SBP may have developed a quinolone resistant flora, quinolones should not be used in these patients[6].

Failure of the initial antibiotic treatment should be considered in patients in whom the initial neutrophil count does not decrease below 25% of the pre-treatment value after two days of treatment[117]. Treatment failure might be due to bacteria resistant to the initial treatment or secondary peritonitis. Under these circumstances, treatment has to be modified according to susceptibility testing (if available) or on an empiric basis.

The addition of intravenous albumin to cefotaxime in the treatment of SBP has been shown to be effective in two studies[76,118]. One controlled randomized trial compared patients with SBP receiving cefotaxime alone vs patients with cefotaxime plus albumin 1.5 g/kg body weight at diagnosis, followed by 1 g/kg albumin on day 3. The study revealed a decrease in mortality from 29% in the cefotaxime group to 10% in the cefotaxime/albumin group[76]. The study by Sigal et al[118] found that combination treatment with albumin is particularly effective in patients with an impaired liver and kidney function (bilirubin > 4 mg/dL and creatinine > 1 mg/dL, respectively) but that combination treatment with albumin is not necessary in patients who do not fulfil these criteria.

In patients who promptly respond to antibiotic treatment, a follow-up paracentesis and ascitic fluid analysis is not necessary[6]. In patients who do not respond to treatment or show a delayed response, a follow-up ascitic fluid analysis is mandatory for further evaluation[119].

Several subgroups of patients at high risk for the development of SBP have been identified in the past. Risk factors for SBP are ascitic fluid protein concentration < 1.0 g/dL, variceal hemorrhage and a prior episode of SBP[6]. Several randomized controlled trials have shown a benefit of prophylactic antibiotic treatment in these patients[120-126].

Variceal bleeding is a major risk factor for the development of SBP, especially in patients with advanced cirrhosis and severe bleeding[120,126-134]. Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with variceal hemorrhage has been shown to not only decrease the rate of SBP[8,101,106] but also decrease the risk for rebleeding[135] and hospital mortality[128].

Norfloxacin (400 mg twice daily) for 7 d has been widely used for selective intestinal decontamination in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding[8,101,126]. In patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and advanced cirrhosis, intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g/d for 7 d) has been shown to be superior to norfloxacin[121].

Low ascitic fluid protein concentration (< 1.0 g/dL) is a risk factor for the development of SBP[123,136-138] and prophylactic antibiotic treatment is advisable in these patients. Most data are available for prophylaxis of SBP using norfloxacin[125,139-142]. One randomized trial in which patients with low ascitic fluid protein concentration (< 1.0 g/dL) or a bilirubin > 2.5 mg/dL were treated with continuous norfloxacin or inpatient-only norfloxacin showed that the incidence of SBP was lower in the continuous treatment group at the expense of more resistant flora when they did develop infection[141]. These findings were substantiated by another randomized trial comparing daily norfloxacin (400 mg for twelve months) with placebo in patients with low ascitic fluid protein concentration (< 1.5 g/dL) and an impaired liver or kidney function[139]. The patients in the verum group had a lower incidence of SBP and hepatorenal syndrome as well as a survival advantage (after three months but not after one year) compared to the patients receiving placebo[139].

Another randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial compared ciprofloxacin 500 mg/d for twelve months with placebo in patients with ascitic fluid protein concentration less than 1.5 g/dL and impaired liver function (Child-Pugh score 8.3 ± 1.3 and 8.5 ± 1.5, in the placebo and ciprofloxacin group, respectively)[142]. The study revealed a trend towards a lower incidence of SBP in the ciprofloxacin group but the result was not significant. Nevertheless, the 1-year survival was higher in the patients in the ciprofloxacin group[142]. This might be attributed to the fact that the probability of remaining free of bacterial infections was higher in the ciprofloxacin group[142].

The overall recurrence rate of SBP in patients surviving the first episode of SBP is approximately 70% in the first year[106] and survival rates are 30%-50% and 25%-30% in the first and second year after SBP, respectively. Norfloxacin is effective in the secondary prophylaxis of SBP. One randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study revealed that prophylactic treatment with 400 mg/d norfloxacin reduced the recurrence rate of SBP from 68% to 20%[122]. Another trial compared norfloxacin 400 mg/d with rufloxacin 400 mg/wk and did not find a significant difference in the SBP recurrence rate between the two treatment groups[143]. The effects of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin were assessed in three more studies[124,125,144]. All three studies revealed a reduced occurrence of SBP in the patients receiving prophylactic treatment. However, the significance of the studies in the setting of secondary prophylaxis is limited since the studies included patients with and without prior episodes of SBP. There are no trials available that have studied for how long secondary prophylaxis should be given.

Peer reviewer: Ferruccio Bonino, Professor, Chief Scientific Officer, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Mangiagalli e Regina Elena, Via F. Sforza 28, 20122 Milano, Italy

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Ginés P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Terés J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, Caballería J, Rodés J, Rozman C. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7:122-128. |

| 2. | Planas R, Montoliu S, Ballesté B, Rivera M, Miquel M, Masnou H, Galeras JA, Giménez MD, Santos J, Cirera I. Natural history of patients hospitalized for management of cirrhotic ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1385-1394. |

| 3. | Arroyo V, Ginès P, Gerbes AL, Dudley FJ, Gentilini P, Laffi G, Reynolds TB, Ring-Larsen H, Schölmerich J. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 1996;23:164-176. |

| 4. | Runyon BA. Paracentesis of ascitic fluid. A safe procedure. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:2259-2261. |

| 5. | Webster ST, Brown KL, Lucey MR, Nostrant TT. Hemorrhagic complications of large volume abdominal paracentesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:366-368. |

| 6. | Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:2087-2107. |

| 7. | Grabau CM, Crago SF, Hoff LK, Simon JA, Melton CA, Ott BJ, Kamath PS. Performance standards for therapeutic abdominal paracentesis. Hepatology. 2004;40:484-488. |

| 8. | Rimola A, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142-153. |

| 9. | Runyon BA, Hoefs JC, Morgan TR. Ascitic fluid analysis in malignancy-related ascites. Hepatology. 1988;8:1104-1109. |

| 10. | Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, Angeli P, Porayko M, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258-266. |

| 11. | Runyon BA, Montano AA, Akriviadis EA, Antillon MR, Irving MA, McHutchison JG. The serum-ascites albumin gradient is superior to the exudate-transudate concept in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:215-220. |

| 12. | Veldt BJ, Lainé F, Guillygomarc'h A, Lauvin L, Boudjema K, Messner M, Brissot P, Deugnier Y, Moirand R. Indication of liver transplantation in severe alcoholic liver cirrhosis: quantitative evaluation and optimal timing. J Hepatol. 2002;36:93-98. |

| 13. | Yao FY, Bass NM. Lamivudine treatment in patients with severely decompensated cirrhosis due to replicating hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2000;33:301-307. |

| 14. | Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252. |

| 15. | Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S. 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105-1187. |

| 16. | Soulsby CT, Madden AM, Morgan MY. The effect of dietary sodium restriction on energy and protein intake in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1997;26 Suppl:382A: 1013. |

| 17. | Gauthier A, Levy VG, Quinton A, Michel H, Rueff B, Descos L, Durbec JP, Fermanian J, Lancrenon S. Salt or no salt in the treatment of cirrhotic ascites: a randomised study. Gut. 1986;27:705-709. |

| 18. | Bernardi M, Laffi G, Salvagnini M, Azzena G, Bonato S, Marra F, Trevisani F, Gasbarrini G, Naccarato R, Gentilini P. Efficacy and safety of the stepped care medical treatment of ascites in liver cirrhosis: a randomized controlled clinical trial comparing two diets with different sodium content. Liver. 1993;13:156-162. |

| 19. | Angeli P, Wong F, Watson H, Ginès P. Hyponatremia in cirrhosis: Results of a patient population survey. Hepatology. 2006;44:1535-1542. |

| 20. | Biggins SW, Kim WR, Terrault NA, Saab S, Balan V, Schiano T, Benson J, Therneau T, Kremers W, Wiesner R. Evidence-based incorporation of serum sodium concentration into MELD. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1652-1660. |

| 21. | Sterns RH. Severe symptomatic hyponatremia: treatment and outcome. A study of 64 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:656-664. |

| 22. | Bernardi M, Servadei D, Trevisani F, Rusticali AG, Gasbarrini G. Importance of plasma aldosterone concentration on the natriuretic effect of spironolactone in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Digestion. 1985;31:189-193. |

| 23. | Pérez-Ayuso RM, Arroyo V, Planas R, Gaya J, Bory F, Rimola A, Rivera F, Rodés J. Randomized comparative study of efficacy of furosemide versus spironolactone in nonazotemic cirrhosis with ascites. Relationship between the diuretic response and the activity of the renin-aldosterone system. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:961-968. |

| 24. | Fogel MR, Sawhney VK, Neal EA, Miller RG, Knauer CM, Gregory PB. Diuresis in the ascitic patient: a randomized controlled trial of three regimens. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3 Suppl 1:73-80. |

| 25. | Gatta A, Angeli P, Caregaro L, Menon F, Sacerdoti D, Merkel C. A pathophysiological interpretation of unresponsiveness to spironolactone in a stepped-care approach to the diuretic treatment of ascites in nonazotemic cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 1991;14:231-236. |

| 26. | Pockros PJ, Reynolds TB. Rapid diuresis in patients with ascites from chronic liver disease: the importance of peripheral edema. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:1827-1833. |

| 27. | Daskalopoulos G, Laffi G, Morgan T, Pinzani M, Harley H, Reynolds T, Zipser RD. Immediate effects of furosemide on renal hemodynamics in chronic liver disease with ascites. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1859-1863. |

| 28. | Sawhney VK, Gregory PB, Swezey SE, Blaschke TF. Furosemide disposition in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:1012-1016. |

| 29. | Stanley MM, Ochi S, Lee KK, Nemchausky BA, Greenlee HB, Allen JI, Allen MJ, Baum RA, Gadacz TR, Camara DS. Peritoneovenous shunting as compared with medical treatment in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and massive ascites. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study on Treatment of Alcoholic Cirrhosis with Ascites. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1632-1638. |

| 30. | Angeli P, Fasolato S, Mazza E, Okolicsanyi L, Maresio G, Velo E, Galioto A, Salinas F, D'Aquino M, Sticca A. Combined versus sequential diuretic treatment of ascites in non-azotaemic patients with cirrhosis: results of an open randomised clinical trial. Gut. 2010;59:98-104. |

| 31. | Santos J, Planas R, Pardo A, Durández R, Cabré E, Morillas RM, Granada ML, Jiménez JA, Quintero E, Gassull MA. Spironolactone alone or in combination with furosemide in the treatment of moderate ascites in nonazotemic cirrhosis. A randomized comparative study of efficacy and safety. J Hepatol. 2003;39:187-192. |

| 32. | Runyon BA. Care of patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:337-342. |

| 33. | Abecasis R, Guevara M, Miguez C, Cobas S, Terg R. Long-term efficacy of torsemide compared with frusemide in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:309-313. |

| 34. | Fiaccadori F, Pedretti G, Pasetti G, Pizzaferri P, Elia G. Torasemide versus furosemide in cirrhosis: a long-term, double-blind, randomized clinical study. Clin Investig. 1993;71:579-584. |

| 35. | Gerbes AL, Bertheau-Reitha U, Falkner C, Jüngst D, Paumgartner G. Advantages of the new loop diuretic torasemide over furosemide in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. A randomized, double blind cross-over trial. J Hepatol. 1993;17:353-358. |

| 36. | Angeli P, Dalla Pria M, De Bei E, Albino G, Caregaro L, Merkel C, Ceolotto G, Gatta A. Randomized clinical study of the efficacy of amiloride and potassium canrenoate in nonazotemic cirrhotic patients with ascites. Hepatology. 1994;19:72-79. |

| 37. | Guardiola J, Baliellas C, Xiol X, Fernandez Esparrach G, Ginès P, Ventura P, Vazquez S. External validation of a prognostic model for predicting survival of cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2374-2378. |

| 38. | Moreau R, Delègue P, Pessione F, Hillaire S, Durand F, Lebrec D, Valla DC. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Liver Int. 2004;24:457-464. |

| 39. | Matsumura K, Nakase E, Haiyama T, Takeo K, Shimizu K, Yamasaki K, Kohno K. Determination of cardiac ejection fraction and left ventricular volume: contrast-enhanced ultrafast cine MR imaging vs IV digital subtraction ventriculography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:979-985. |

| 40. | Pache I, Bilodeau M. Severe haemorrhage following abdominal paracentesis for ascites in patients with liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:525-529. |

| 41. | Ginès A, Fernández-Esparrach G, Monescillo A, Vila C, Domènech E, Abecasis R, Angeli P, Ruiz-Del-Arbol L, Planas R, Solà R. Randomized trial comparing albumin, dextran 70, and polygeline in cirrhotic patients with ascites treated by paracentesis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1002-1010. |

| 42. | Ginès P, Titó L, Arroyo V, Planas R, Panés J, Viver J, Torres M, Humbert P, Rimola A, Llach J. Randomized comparative study of therapeutic paracentesis with and without intravenous albumin in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1493-1502. |

| 43. | Pozzi M, Osculati G, Boari G, Serboli P, Colombo P, Lambrughi C, De Ceglia S, Roffi L, Piperno A, Cusa EN. Time course of circulatory and humoral effects of rapid total paracentesis in cirrhotic patients with tense, refractory ascites. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:709-719. |

| 44. | Solà R, Vila MC, Andreu M, Oliver MI, Coll S, Gana J, Ledesma S, Ginès P, Jiménez W, Arroyo V. Total paracentesis with dextran 40 vs diuretics in the treatment of ascites in cirrhosis: a randomized controlled study. J Hepatol. 1994;20:282-288. |

| 45. | Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Monescillo A, Jimenéz W, Garcia-Plaza A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction: mechanism and effect on hepatic hemodynamics in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:579-586. |

| 46. | Peltekian KM, Wong F, Liu PP, Logan AG, Sherman M, Blendis LM. Cardiovascular, renal, and neurohumoral responses to single large-volume paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and diuretic-resistant ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:394-399. |

| 47. | Titó L, Ginès P, Arroyo V, Planas R, Panés J, Rimola A, Llach J, Humbert P, Badalamenti S, Jiménez W. Total paracentesis associated with intravenous albumin management of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:146-151. |

| 48. | Saló J, Ginès A, Ginès P, Piera C, Jiménez W, Guevara M, Fernández-Esparrach G, Sort P, Bataller R, Arroyo V. Effect of therapeutic paracentesis on plasma volume and transvascular escape rate of albumin in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;27:645-653. |

| 49. | Moreau R, Valla DC, Durand-Zaleski I, Bronowicki JP, Durand F, Chaput JC, Dadamessi I, Silvain C, Bonny C, Oberti F. Comparison of outcome in patients with cirrhosis and ascites following treatment with albumin or a synthetic colloid: a randomised controlled pilot trail. Liver Int. 2006;26:46-54. |

| 50. | Sola-Vera J, Miñana J, Ricart E, Planella M, González B, Torras X, Rodríguez J, Such J, Pascual S, Soriano G. Randomized trial comparing albumin and saline in the prevention of paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37:1147-1153. |

| 51. | Fernández-Esparrach G, Guevara M, Sort P, Pardo A, Jiménez W, Ginès P, Planas R, Lebrec D, Geuvel A, Elewaut A. Diuretic requirements after therapeutic paracentesis in non-azotemic patients with cirrhosis. A randomized double-blind trial of spironolactone versus placebo. J Hepatol. 1997;26:614-620. |

| 52. | Ochs A, Rössle M, Haag K, Hauenstein KH, Deibert P, Siegerstetter V, Huonker M, Langer M, Blum HE. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for refractory ascites. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1192-1197. |

| 53. | Ginès P, Uriz J, Calahorra B, Garcia-Tsao G, Kamath PS, Del Arbol LR, Planas R, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting versus paracentesis plus albumin for refractory ascites in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1839-1847. |

| 54. | Lebrec D, Giuily N, Hadengue A, Vilgrain V, Moreau R, Poynard T, Gadano A, Lassen C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: comparison with paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites: a randomized trial. French Group of Clinicians and a Group of Biologists. J Hepatol. 1996;25:135-144. |

| 55. | Rössle M, Ochs A, Gülberg V, Siegerstetter V, Holl J, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701-1707. |

| 56. | Salerno F, Merli M, Riggio O, Cazzaniga M, Valeriano V, Pozzi M, Nicolini A, Salvatori F. Randomized controlled study of TIPS versus paracentesis plus albumin in cirrhosis with severe ascites. Hepatology. 2004;40:629-635. |

| 57. | Sanyal AJ, Genning C, Reddy KR, Wong F, Kowdley KV, Benner K, McCashland T. The North American Study for the Treatment of Refractory Ascites. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:634-641. |

| 58. | Colombato LA, Spahr L, Martinet JP, Dufresne MP, Lafortune M, Fenyves D, Pomier-Layrargues G. Haemodynamic adaptation two months after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in cirrhotic patients. Gut. 1996;39:600-604. |

| 59. | Gerbes AL, Gülberg V, Waggershauser T, Holl J, Reiser M. Renal effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhosis: comparison of patients with ascites, with refractory ascites, or without ascites. Hepatology. 1998;28:683-688. |

| 60. | Guevara M, Ginès P, Bandi JC, Gilabert R, Sort P, Jiménez W, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in hepatorenal syndrome: effects on renal function and vasoactive systems. Hepatology. 1998;28:416-422. |

| 61. | Huonker M, Schumacher YO, Ochs A, Sorichter S, Keul J, Rössle M. Cardiac function and haemodynamics in alcoholic cirrhosis and effects of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt. Gut. 1999;44:743-748. |

| 62. | Lotterer E, Wengert A, Fleig WE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: short-term and long-term effects on hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:632-639. |

| 63. | Merli M, Valeriano V, Funaro S, Attili AF, Masini A, Efrati C, De CS, Riggio O. Modifications of cardiac function in cirrhotic patients treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:142-148. |

| 64. | Quiroga J, Sangro B, Núñez M, Bilbao I, Longo J, García-Villarreal L, Zozaya JM, Betés M, Herrero JI, Prieto J. Transjugular intrahepatic portal-systemic shunt in the treatment of refractory ascites: effect on clinical, renal, humoral, and hemodynamic parameters. Hepatology. 1995;21:986-994. |

| 65. | Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP 3rd, Shiffman ML, DeMeo J, Cole PE, Tisnado J. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:889-898. |

| 66. | Wong F, Sniderman K, Liu P, Allidina Y, Sherman M, Blendis L. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: effects on hemodynamics and sodium homeostasis in cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:816-822. |

| 67. | Wong F, Sniderman K, Liu P, Blendis L. The mechanism of the initial natriuresis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:899-907. |

| 68. | Salerno F, Cammà C, Enea M, Rössle M, Wong F. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:825-834. |

| 69. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386-400. |

| 70. | Riggio O, Angeloni S, Salvatori FM, De Santis A, Cerini F, Farcomeni A, Attili AF, Merli M. Incidence, natural history, and risk factors of hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent grafts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2738-2746. |

| 71. | Casado M, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, Bru C, Bañares R, Bandi JC, Escorsell A, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Gilabert R, Feu F. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1296-1303. |

| 72. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L, Bilbao JI, Bosch J, Rousseau H, Vinel JP. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. |

| 73. | Angermayr B, Cejna M, Koenig F, Karnel F, Hackl F, Gangl A, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: ePTFE-covered stentgrafts versus bare stents. Hepatology. 2003;38:1043-1050. |

| 74. | Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310-1318. |

| 75. | Fasolato S, Angeli P, Dallagnese L, Maresio G, Zola E, Mazza E, Salinas F, Donà S, Fagiuoli S, Sticca A. Renal failure and bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Hepatology. 2007;45:223-229. |

| 76. | Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Aldeguer X, Planas R, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Castells L, Vargas V, Soriano G, Guevara M. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403-409. |

| 77. | Terra C, Guevara M, Torre A, Gilabert R, Fernández J, Martín-Llahí M, Baccaro ME, Navasa M, Bru C, Arroyo V. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis and sepsis unrelated to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: value of MELD score. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1944-1953. |

| 78. | Thabut D, Massard J, Gangloff A, Carbonell N, Francoz C, Nguyen-Khac E, Duhamel C, Lebrec D, Poynard T, Moreau R. Model for end-stage liver disease score and systemic inflammatory response are major prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis and acute functional renal failure. Hepatology. 2007;46:1872-1882. |

| 80. | Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1279-1290. |

| 81. | Alessandria C, Ozdogan O, Guevara M, Restuccia T, Jiménez W, Arroyo V, Rodés J, Ginès P. MELD score and clinical type predict prognosis in hepatorenal syndrome: relevance to liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1282-1289. |

| 82. | Sharma P, Kumar A, Shrama BC, Sarin SK. An open label, pilot, randomized controlled trial of noradrenaline versus terlipressin in the treatment of type 1 hepatorenal syndrome and predictors of response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1689-1697. |

| 83. | Kiser TH, Fish DN, Obritsch MD, Jung R, MacLaren R, Parikh CR. Vasopressin, not octreotide, may be beneficial in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a retrospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1813-1820. |

| 84. | Pomier-Layrargues G, Paquin SC, Hassoun Z, Lafortune M, Tran A. Octreotide in hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Hepatology. 2003;38:238-243. |

| 85. | Angeli P, Volpin R, Gerunda G, Craighero R, Roner P, Merenda R, Amodio P, Sticca A, Caregaro L, Maffei-Faccioli A. Reversal of type 1 hepatorenal syndrome with the administration of midodrine and octreotide. Hepatology. 1999;29:1690-1697. |

| 86. | Esrailian E, Pantangco ER, Kyulo NL, Hu KQ, Runyon BA. Octreotide/Midodrine therapy significantly improves renal function and 30-day survival in patients with type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:742-748. |

| 87. | Nazar A, Pereira GH, Guevara M, Martín-Llahi M, Pepin MN, Marinelli M, Solá E, Baccaro ME, Terra C, Arroyo V. Predictors of response to therapy with terlipressin and albumin in patients with cirrhosis and type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Hepatology. 2010;51:219-226. |

| 88. | Ginès P, Guevara M. Therapy with vasoconstrictor drugs in cirrhosis: The time has arrived. Hepatology. 2007;46:1685-1687. |

| 89. | Martín-Llahí M, Pépin MN, Guevara M, Díaz F, Torre A, Monescillo A, Soriano G, Terra C, Fábrega E, Arroyo V. Terlipressin and albumin vs albumin in patients with cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1352-1359. |

| 90. | Ortega R, Ginès P, Uriz J, Cárdenas A, Calahorra B, De Las Heras D, Guevara M, Bataller R, Jiménez W, Arroyo V. Terlipressin therapy with and without albumin for patients with hepatorenal syndrome: results of a prospective, nonrandomized study. Hepatology. 2002;36:941-948. |

| 91. | Alessandria C, Venon WD, Marzano A, Barletti C, Fadda M, Rizzetto M. Renal failure in cirrhotic patients: role of terlipressin in clinical approach to hepatorenal syndrome type 2. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1363-1368. |

| 92. | Testino G, Ferro C, Sumberaz A, Messa P, Morelli N, Guadagni B, Ardizzone G, Valente U. Type-2 hepatorenal syndrome and refractory ascites: role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in eighteen patients with advanced cirrhosis awaiting orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1753-1755. |

| 93. | Brensing KA, Textor J, Perz J, Schiedermaier P, Raab P, Strunk H, Klehr HU, Kramer HJ, Spengler U, Schild H. Long term outcome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in non-transplant cirrhotics with hepatorenal syndrome: a phase II study. Gut. 2000;47:288-295. |

| 94. | Capling RK, Bastani B. The clinical course of patients with type 1 hepatorenal syndrome maintained on hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2004;26:563-568. |

| 95. | Keller F, Heinze H, Jochimsen F, Passfall J, Schuppan D, Büttner P. Risk factors and outcome of 107 patients with decompensated liver disease and acute renal failure (including 26 patients with hepatorenal syndrome): the role of hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 1995;17:135-146. |

| 96. | Gonwa TA, Morris CA, Goldstein RM, Husberg BS, Klintmalm GB. Long-term survival and renal function following liver transplantation in patients with and without hepatorenal syndrome--experience in 300 patients. Transplantation. 1991;51:428-430. |

| 97. | Charlton MR, Wall WJ, Ojo AO, Ginès P, Textor S, Shihab FS, Marotta P, Cantarovich M, Eason JD, Wiesner RH. Report of the first international liver transplantation society expert panel consensus conference on renal insufficiency in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:S1-S34. |

| 98. | Jeyarajah DR, Gonwa TA, McBride M, Testa G, Abbasoglu O, Husberg BS, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, Klintmalm GB. Hepatorenal syndrome: combined liver kidney transplants versus isolated liver transplant. Transplantation. 1997;64:1760-1765. |

| 99. | Caly WR, Strauss E. A prospective study of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1993;18:353-358. |

| 100. | Fernández J, Navasa M, Gómez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35:140-148. |

| 101. | Wong F, Bernardi M, Balk R, Christman B, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Patch D, Soriano G, Hoefs J, Navasa M. Sepsis in cirrhosis: report on the 7th meeting of the International Ascites Club. Gut. 2005;54:718-725. |

| 102. | Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37:897-901. |

| 103. | Nousbaum JB, Cadranel JF, Nahon P, Khac EN, Moreau R, Thévenot T, Silvain C, Bureau C, Nouel O, Pilette C, Paupard T, Vanbiervliet G, Oberti F, Davion T, Jouannaud V, Roche B, Bernard PH, Beaulieu S, Danne O, Thabut D, Chagneau-Derrode C, de Lédinghen V, Mathurin P, Pauwels A, Bronowicki JP, Habersetzer F, Abergel A, Audigier JC, Sapey T, Grangé JD, Tran A. Diagnostic accuracy of the Multistix 8 SG reagent strip in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1275-1281. |

| 104. | Plessier A, Denninger MH, Consigny Y, Pessione F, Francoz C, Durand F, Francque S, Bezeaud A, Chauvelot-Moachon L, Lebrec D. Coagulation disorders in patients with cirrhosis and severe sepsis. Liver Int. 2003;23:440-448. |

| 105. | Hoefs JC. Serum protein concentration and portal pressure determine the ascitic fluid protein concentration in patients with chronic liver disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1983;102:260-273. |

| 106. | Garcia-Tsao G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:726-748. |

| 107. | Runyon BA, Antillon MR. Ascitic fluid pH and lactate: insensitive and nonspecific tests in detecting ascitic fluid infection. Hepatology. 1991;13:929-935. |

| 108. | Nguyen-Khac E, Cadranel JF, Thevenot T, Nousbaum JB. Review article: the utility of reagent strips in the diagnosis of infected ascites in cirrhotic patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:282-288. |

| 109. | Runyon BA. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites: a variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 1990;12:710-715. |

| 110. | Felisart J, Rimola A, Arroyo V, Perez-Ayuso RM, Quintero E, Gines P, Rodes J. Cefotaxime is more effective than is ampicillin-tobramycin in cirrhotics with severe infections. Hepatology. 1985;5:457-462. |

| 111. | Rimola A, Salmerón JM, Clemente G, Rodrigo L, Obrador A, Miranda ML, Guarner C, Planas R, Solá R, Vargas V. Two different dosages of cefotaxime in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: results of a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Hepatology. 1995;21:674-679. |

| 112. | Runyon BA, McHutchison JG, Antillon MR, Akriviadis EA, Montano AA. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A randomized controlled study of 100 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1737-1742. |

| 113. | Baskol M, Gursoy S, Baskol G, Ozbakir O, Guven K, Yucesoy M. Five days of ceftriaxone to treat culture negative neutrocytic ascites in cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:403-405. |

| 114. | Ricart E, Soriano G, Novella MT, Ortiz J, Sàbat M, Kolle L, Sola-Vera J, Miñana J, Dedéu JM, Gómez C. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid versus cefotaxime in the therapy of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2000;32:596-602. |

| 115. | Terg R, Cobas S, Fassio E, Landeira G, Ríos B, Vasen W, Abecasis R, Ríos H, Guevara M. Oral ciprofloxacin after a short course of intravenous ciprofloxacin in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: results of a multicenter, randomized study. J Hepatol. 2000;33:564-569. |

| 116. | Navasa M, Follo A, Llovet JM, Clemente G, Vargas V, Rimola A, Marco F, Guarner C, Forné M, Planas R. Randomized, comparative study of oral ofloxacin versus intravenous cefotaxime in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1011-1017. |

| 117. | Guarner C, Soriano G. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17:203-217. |

| 118. | Sigal SH, Stanca CM, Fernandez J, Arroyo V, Navasa M. Restricted use of albumin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut. 2007;56:597-599. |

| 119. | Akriviadis EA, Runyon BA. Utility of an algorithm in differentiating spontaneous from secondary bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:127-133. |

| 120. | Blaise M, Pateron D, Trinchet JC, Levacher S, Beaugrand M, Pourriat JL. Systemic antibiotic therapy prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1994;20:34-38. |

| 121. | Fernández J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gómez C, Durandez R, Serradilla R, Guarner C, Planas R, Arroyo V, Navasa M. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1049-1056; quiz 1285. |

| 122. | Ginés P, Rimola A, Planas R, Vargas V, Marco F, Almela M, Forné M, Miranda ML, Llach J, Salmerón JM. Norfloxacin prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence in cirrhosis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology. 1990;12:716-724. |

| 123. | Runyon BA. Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1343-1346. |

| 124. | Singh N, Gayowski T, Yu VL, Wagener MM. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:595-598. |

| 125. | Soriano G, Guarner C, Teixidó M, Such J, Barrios J, Enríquez J, Vilardell F. Selective intestinal decontamination prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:477-481. |

| 126. | Soriano G, Guarner C, Tomás A, Villanueva C, Torras X, González D, Sainz S, Anguera A, Cussó X, Balanzó J. Norfloxacin prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotics with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1267-1272. |

| 127. | Bernard B, Cadranel JF, Valla D, Escolano S, Jarlier V, Opolon P. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1828-1834. |

| 128. | Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655-1661. |

| 129. | Bleichner G, Boulanger R, Squara P, Sollet JP, Parent A. Frequency of infections in cirrhotic patients presenting with acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1986;73:724-726. |

| 130. | Deschênes M, Villeneuve JP. Risk factors for the development of bacterial infections in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2193-2197. |

| 131. | Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Kuo BI, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:746-753. |

| 132. | Hsieh WJ, Lin HC, Hwang SJ, Hou MC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. The effect of ciprofloxacin in the prevention of bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis after upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:962-966. |

| 133. | Pauwels A, Mostefa-Kara N, Debenes B, Degoutte E, Lévy VG. Systemic antibiotic prophylaxis after gastrointestinal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients with a high risk of infection. Hepatology. 1996;24:802-806. |

| 134. | Rimola A, Bory F, Teres J, Perez-Ayuso RM, Arroyo V, Rodes J. Oral, nonabsorbable antibiotics prevent infection in cirrhotics with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1985;5:463-467. |

| 135. | Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Tur-Kaspa R, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD002907. |

| 136. | Andreu M, Sola R, Sitges-Serra A, Alia C, Gallen M, Vila MC, Coll S, Oliver MI. Risk factors for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1133-1138. |

| 137. | Llach J, Rimola A, Navasa M, Ginès P, Salmerón JM, Ginès A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Incidence and predictive factors of first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis with ascites: relevance of ascitic fluid protein concentration. Hepatology. 1992;16:724-727. |

| 138. | Guarner C, Solà R, Soriano G, Andreu M, Novella MT, Vila MC, Sàbat M, Coll S, Ortiz J, Gómez C. Risk of a first community-acquired spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotics with low ascitic fluid protein levels. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:414-419. |

| 139. | Fernández J, Navasa M, Planas R, Montoliu S, Monfort D, Soriano G, Vila C, Pardo A, Quintero E, Vargas V. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:818-824. |

| 140. | Grangé JD, Roulot D, Pelletier G, Pariente EA, Denis J, Ink O, Blanc P, Richardet JP, Vinel JP, Delisle F. Norfloxacin primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with ascites: a double-blind randomized trial. J Hepatol. 1998;29:430-436. |

| 141. | Novella M, Solà R, Soriano G, Andreu M, Gana J, Ortiz J, Coll S, Sàbat M, Vila MC, Guarner C. Continuous versus inpatient prophylaxis of the first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with norfloxacin. Hepatology. 1997;25:532-536. |

| 142. | Terg R, Fassio E, Guevara M, Cartier M, Longo C, Lucero R, Landeira C, Romero G, Dominguez N, Muñoz A. Ciprofloxacin in primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2008;48:774-779. |

| 143. | Bauer TM, Follo A, Navasa M, Vila J, Planas R, Clemente G, Vargas V, Bory F, Vaquer P, Rodés J. Daily norfloxacin is more effective than weekly rufloxacin in prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1356-1361. |

| 144. | Rolachon A, Cordier L, Bacq Y, Nousbaum JB, Franza A, Paris JC, Fratte S, Bohn B, Kitmacher P, Stahl JP. Ciprofloxacin and long-term prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: results of a prospective controlled trial. Hepatology. 1995;22:1171-1174. |