Published online Feb 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.992

Revised: December 19, 2009

Accepted: December 26, 2009

Published online: February 28, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic examination of blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel.

METHODS: We retrospectively studied 15 patients who underwent massive bowel resection with enterostomy for superior mesenteric arterial occlusion (SMAO); the patients were divided into a delayed closure group (D group) and an early closure group (E group).

RESULTS: The mean duration from initial operation to enterostomy closure was significantly shorter in the E group (18.3 ± 2.1 d) than in the D group (34.3 ± 5.9 d) (P < 0.0001). The duration of hospitalization after surgery was significantly shorter in the E group (33 ± 2.2 d) than in the D group (51 ± 8.9 d) (P < 0.0002).

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic examination of blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel is useful to assess the feasibility of early closure of enterostomy in SMAO cases.

- Citation: Oida T, Kano H, Mimatsu K, Kawasaki A, Kuboi Y, Fukino N, Amano S. Endoscopy-based early enterostomy closure for superior mesenteric arterial occlusion. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(8): 992-996

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i8/992.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.992

Construction of a temporary stoma is a relatively common surgical procedure. A transient stoma is known to lower the operative risk, but it should be closed at the earliest opportunity; however, in the literature, the morbidity and mortality rates after ileostomy or colostomy closure are rather high[1-8]. Several studies have compared colostomy closure and ileostomy closure, and found that a multitude of factors influence the development of complications after stoma closure, such as perioperative treatment, time of operation, and surgical technique[9-12]. Patients with superior mesenteric arterial occlusion (SMAO) often require massive bowel resection because of considerable intestinal necrosis. Massive intestinal resection often causes short-bowel syndrome and necessitates parenteral nutrition. In order to avoid the development of this syndrome, it is important to retain as much of the remnant bowel as possible. SMAO is known to frequently occur in patients with atrial fibrillation; hence, even if the patients survive after the initial operation, the risk of disease recurrence remains considerably high. Moreover, reperfusion injury may occur in SMAO patients, thereby causing unstable hemodynamics and multiple organ failure[13,14]. Calvien et al[15] reported that bowel infarction recurred in 32% of patients early after the resection of the necrotic bowel. In the case of enterostomy, it is difficult to determine the timing of enterostomy closure after the initial operation. In order to assess the feasibility of early closure and its outcome, we endoscopically inspected blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel of stoma patients and defined a minimal delay as optimal for closing small bowel stomas. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of endoscopic examination of blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel.

We retrospectively studied 15 patients (12 men and 3 women; age range: 57-74 years; mean age: 68 years) who had undergone massive bowel resection with enterostomy for SMAO between April 1990 and March 2009 at the Department of Surgery, Social Insurance Yokohama Central Hospital, Yokohama, Japan. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the timing of enterostomy closure: delayed closure group (D group) and early closure group (E group). All patients gave written informed consent to this study.

The technique used for stoma closure did not differ between the E and D groups. In brief, after thorough mobilization of the bowel via a parastomal incision, a stoma was excised and the adhesions between the bowel and the peritoneum and omentum were cleared. Both the bowel ends were resected, and sutured manually with 2-layered end-to-end anastomosis.

After initial surgery, when there was an improvement in the small intestinal dilatation and sufficient bowel movement was observed, the patients were allowed to resume a normal diet. Subsequently, parenteral nutritional support was initiated for the patients in whom oral intake was not sufficient, or for those with severe diarrhea. The clinical findings were confirmed as positive when (1) oral intake was sufficient; (2) diarrhea was controlled by medications; and (3) initial disease was sufficiently controlled without recurrence. When these criteria were satisfied, enterostomy closure was performed. These patients were classified as group D.

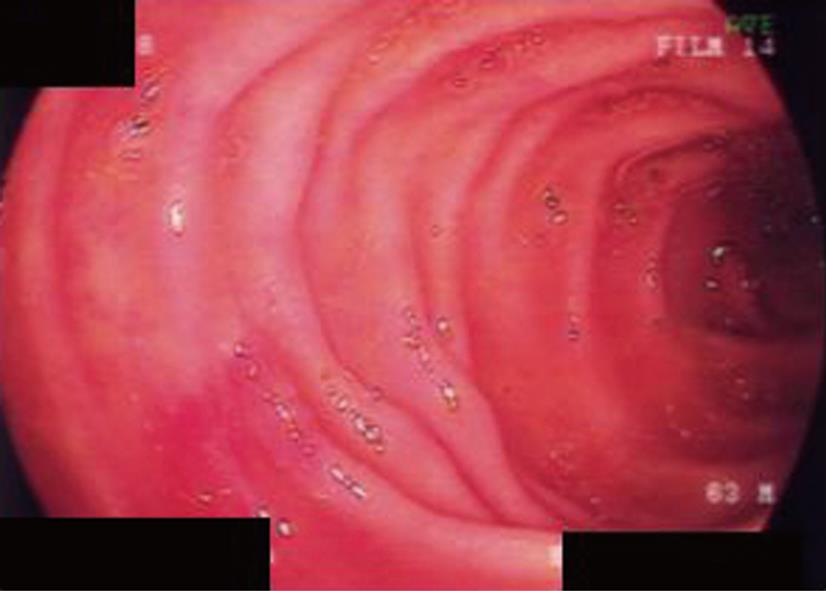

After initial surgery, when there was an improvement in the small intestinal dilatation and sufficient bowel movement was observed, endoscopic examination was performed. We used a cholangioendoscope (Olympus CHF Type P20Q; Olympus Medical Systems Co. Tokyo, Japan) for endoscopy, and it was inserted from the opening of the enterostomy.

The endoscopic findings were confirmed as positive when (1) sufficient blood flow resumed in the remnant bowel; and (2) the bowel edema subsided. Enterostomy closure was performed when these criteria were satisfied (Figure 1). However, if the criteria were not met, endoscopic examination was performed again after 3 d. These patients were classified as group E.

Results are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise stated. Univariate analysis was performed using Student’s t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test for categorical variables. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Delayed closure of enterostomy (D group) was performed in 8 patients and early closure of enterostomy (E group) was performed in 7 patients. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics and initial operative variables. No differences were observed in the mean age and sex ratio between the patient groups. Risk factors and initial diseases for the SMAO patients in the E group were: hypertension in 85.7%, diabetes mellitus in 57.1%, atrial fibrillation in 57.1%, and apoplexy in 14.3%; while those for the patients in the D group were: hypertension in 65.2%, diabetes mellitus in 62.5%, atrial fibrillation in 37.5%, and apoplexy in 25%. There was no significant difference between the groups with regard to the proportion of patients with risk factors and initial diseases. The mean length of the resected bowel at the initial operation was 265 ± 38 cm in the E group and 239 ± 32 cm in the D group; there was no significant difference between the groups in this regard. All the patients in the E and D groups underwent jejunostomy. No deaths occurred in either of the groups. The most common initial postoperative complication observed was skin erosion, with an incidence rate of 14.3% in the E group, and 37.5% in the D group.

| Early closure group (n = 7) | Delayed closure group (n = 8) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 67.0 ± 4.6 | 69.4 ± 5.6 | < 0.3885 |

| Sex ratio (male:female) | 6:1 | 6:2 | 1 |

| Initial disease | |||

| HT | 6 (85.7) | 5 (62.5) | < 0.5692 |

| DM | 4 (57.1) | 5 (62.5) | 1 |

| Af | 4 (57.1) | 3 (37.5) | < 0.6193 |

| Apo | 1 (14.3) | 2 (25) | 1 |

| Length of resected bowel (cm) | 265 ± 38 | 239 ± 32 | < 0.168 |

| Initial enterostomy complication | |||

| Skin erosion | 1 (14.3) | 3 (37.5) | < 0.5692 |

Table 2 shows the postoperative variables. The mean duration from initial operation to enterostomy closure was significantly shorter in the E group (18.3 ± 2.1 d) than in the D group (34.3 ± 5.9 d) (P < 0.0001). The postoperative complications observed were wound infection and pneumonia, with an incidence rate of 14.3% each in the E group, and 25% each in the D group. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups with regard to postoperative complications (P = 1). The duration of hospitalization after surgery was significantly shorter in the E group (33 ± 2.2 d) than in the D group (51 ± 8.9 d) (P < 0.0002).

Under favorable local or general conditions, a transient small bowel stoma creation may be required to protect a distal anastomosis or to avoid intraperitoneal intestinal anastomosis. It is generally recommended that the temporary stoma be closed within 9-12 wk after its construction[16]. However, because some patients poorly tolerate the temporary stoma owing to extracellular dehydration, difficult pouch fitting, parenteral nutrition requirement in the cases when the stoma is very proximal, and psychological or social impact, it might be advisable to opt for early closure[17].

On the other hand, patients with SMAO often require massive bowel resection because of considerable intestinal necrosis. Massive intestinal resection often causes short-bowel syndrome and necessitates parenteral nutrition. To avoid this syndrome, it is important to retain as much of the remnant bowel as possible. However, SMAO is frequently observed in patients with atrial fibrillation; hence, even if the patients survive after initial operation, the risk of disease recurrence is considered high. Moreover, reperfusion injury may occur in SMAO patients and may cause unstable hemodynamics and multiple organ failure[10,11]. Calvien et al[12] reported that bowel infarction recurred in 32% of the patients early after the resection of necrotic bowel. If we deem primary anastomosis as risky owing to the presence of ischemic changes along the bowel, we perform the bowel resection without anastomosis, and perform an enterostomy. However, a bowel stoma or enterostomy is also a major psychological handicap (altered body schema, odor, uncontrolled emissions, etc.) and causes significant physical stress (risk of severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance). Local care in an intensive care unit needs to be prolonged sometimes, to avoid secondary skin erosions caused by the highly corrosive digestive enzymes. Parenteral nutritional support may also be required if the enterostomy is very proximal, with associated risk of infection caused by the insertion of a central venous catheter. Moreover, it is important to perform early closure of enterostomy to avoid adverse effects on the quality of life of patients. In order to assess the feasibility of early closure of enterostomy, it is necessary to adequately examine the blood flow and edema in the remnant. Thus, we directly examined the blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel of these patients by endoscopy.

Generally, endoscopic examination of the upper digestive tract is performed using esophagogastroduodenoscope, and that of the lower digestive tract (colon and rectum) is performed using colon fiberscope. However, because the opening of the jejunostomy was small in our cases, it would have been difficult to smoothly insert the esophagogastroduodenoscope or colon fiberscope into the small intestine via the jejunostomy. Moreover, these procedures are painful for the patients because the diameters of these endoscopes are relatively large. Hence, we used the cholangioendoscope that has a relatively smaller diameter and can be smoothly inserted into the intestine without causing any pain. A trans-nasal esophagogastroduodenoscope with a small diameter can also be used.

In the case of enterostomy created due to SMAO, it is difficult to determine the timing of enterostomy closure after initial operation. The time chosen for enterostomy closure should be accurately determined taking the following two factors into account: the risk of anastomotic leak that usually occurs between 5 and 7 d[18] postoperatively; the development of dense adhesions due to acute inflammation that appear 2 wk after the creation of the enterostomy[19]. Moreover, the risk of bowel infarction recurrence should be carefully assessed, as high rates have been reported after necrotic bowel resection[15]. Megengaux et al[19] reported that small bowel stomas can be closed on the 10th d after initial surgery, without major complications. Their concept of choosing postoperative day 10 for the closure of stoma was based on the fact that this time point comes after the days when anastomotic leakages are frequently observed, i.e. postoperative days 5-7[18], and before postoperative day 14, thereby ensuring that acute inflammation does not develop. However, because immediate anastomosis is associated with a high risk of dehiscence, Hanish et al[20] suggested that it is preferable to avoid this procedure in stoma patients who present with perforation associated with peritonitis or ischemia due to extensive mesenteric infarction. Because our patients required stoma creation due to SMAO, we considered that it was necessary to precisely investigate the blood flow in the remnant bowel before early closure of the stoma. In the patients of the early closure group, enterostomy closure was performed after 18.3 ± 2.1 d, and no complications associated with anastomosis developed thereafter. This time is significantly shorter compared to the recommended time of 9-12 wk after the construction of enterostomy[16].

Hospitalization in the patients of the early closure group was significantly shorter than that in the patients of the delayed closure group. The incidence rate of complications such as wound infection and pneumonia in the patients of the early closure group was 14.3%, while that of the patients of the delayed closure group was 25%. Although there was no significant difference between groups, the incidence rate of complications was lower in the early closure group than in the delayed closure group.

To the best of our knowledge, early closure of jejunostomy based on endoscopic findings via the stoma has never been studied in patients with SMAO. On the basis of these results, we conclude that endoscopic examination of blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel is a useful predictor to determine the time of enterostomy closure in SMAO cases.

A transient stoma is known to lower the operative risk, but it should be closed at the earliest opportunity; however, the morbidity and mortality rates after ileostomy or colostomy closure are rather high. It is generally recommended that the temporary stoma be closed within 9-12 wk after its construction. Fifteen patients who underwent massive bowel resection with enterostomy for superior mesenteric arterial occlusion (SMAO) were divided into a delayed closure group (D group) and an early closure group (E group).

The mean duration from initial operation to enterostomy closure was significantly shorter in the E group (18.3 ± 2.1 d) than in the D group (34.3 ± 5.9 d) (P < 0.0001). The duration of hospitalization after surgery was significantly shorter in the E group (33 ± 2.2 d) than in the D group (51 ± 8.9 d) (P < 0.0002).

Endoscopic examination of the blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel was found to be useful for assessing the feasibility of early closure of enterostomy in SMAO cases.

In the authors’ study, the number of patients with endoscopic examination of the blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel was very small, but they can propose that endoscopic examination of blood flow and edema in the remnant bowel is a useful predictor to determine the time of enterostomy closure in SMAO cases.

This manuscript is well constructed and the comparison of two methods of the preoperative evaluation clearly delivered. The conclusions were supported by the data. The topic is particularly interesting and up-to-date, because of the lack of surgical procedures to determine the timing of enterostomy closure. The work is written in good English. As a result, the work meets the standards of the World Journal of Gastroenterology. In conclusion the manuscript can be published.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Marek Bebenek, MD, PhD, Department of Surgical Oncology, Regional Comprehensive Cancer Center, pl. Hirszfelda 12, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Wheeler MH, Barker J. Closure of colostomy--a safe procedure? Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20:29-32. |

| 2. | Pittman DM, Smith LE. Complications of colostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:836-843. |

| 3. | Mileski WJ, Rege RV, Joehl RJ, Nahrwold DL. Rates of morbidity and mortality after closure of loop and end colostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;171:17-21. |

| 4. | Demetriades D, Pezikis A, Melissas J, Parekh D, Pickles G. Factors influencing the morbidity of colostomy closure. Am J Surg. 1988;155:594-596. |

| 5. | Bozzetti F, Nava M, Bufalino R, Menotti V, Marolda R, Doci R, Gennari L. Early local complications following colostomy closure in cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:25-29. |

| 6. | Salley RK, Bucher RM, Rodning CB. Colostomy closure. Morbidity reduction employing a semi-standardized protocol. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:319-322. |

| 7. | Rosen L, Friedman IH. Morbidity and mortality following intraperitoneal closure of transverse loop colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:508-512. |

| 9. | Freund HR, Raniel J, Muggia-Sulam M. Factors affecting the morbidity of colostomy closure: a retrospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:712-715. |

| 10. | Köhler A, Athanasiadis S, Nafe M. [Postoperative results of colostomy and ileostomy closure. A retrospective analysis of three different closure techniques in 182 patients]. Chirurg. 1994;65:529-532. |

| 11. | Riesener KP, Lehnen W, Höfer M, Kasperk R, Braun JC, Schumpelick V. Morbidity of ileostomy and colostomy closure: impact of surgical technique and perioperative treatment. World J Surg. 1997;21:103-108. |

| 12. | Garber HI, Morris DM, Eisenstat TE, Coker DD, Annous MO. Factors influencing the morbidity of colostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:464-470. |

| 13. | Mitsuoka H, Unno N, Sakurai T, Kaneko H, Suzuki S, Konno H, Terakawa S, Nakamura S. Pathophysiological role of endothelins in pulmonary microcirculatory disorders due to intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. J Surg Res. 1999;87:143-151. |

| 14. | Mitsuoka H, Kistler EB, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Generation of in vivo activating factors in the ischemic intestine by pancreatic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1772-1777. |

| 16. | Gooszen AW, Geelkerken RH, Hermans J, Lagaay MB, Gooszen HG. Temporary decompression after colorectal surgery: randomized comparison of loop ileostomy and loop colostomy. Br J Surg. 1998;85:76-79. |

| 17. | O'Leary DP, Fide CJ, Foy C, Lucarotti ME. Quality of life after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision and temporary loop ileostomy for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1216-1220. |

| 18. | Rolandelli R, Roslyn JJ. Surgical management and treatment of sepsis associated with gastrointestinal fistulas. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76:1111-1122. |

| 19. | Menegaux F, Jordi-Galais P, Turrin N, Chigot JP. Closure of small bowel stomas on postoperative day 10. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:713-715. |

| 20. | Hanisch E, Schmandra TC, Encke A. Surgical strategies -- anastomosis or stoma, a second look -- when and why? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:239-242. |