Published online Feb 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.631

Revised: September 15, 2009

Accepted: September 22, 2009

Published online: February 7, 2010

AIM: To investigate the incidence, location, clinical presentation, diagnosis and effectiveness of endoscopic treatment of gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) in China.

METHODS: All patients who received emergency upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy due to gastric DL from February 2000 to August 2008 at GI endoscopy center of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University were included in this study. The clinical presentation, medical history, location and characteristics of DL methods and effectiveness of therapy of patients with DL were retrospectively analysed by chart reviews. Long-term follow-up data were collected at outpatient clinics or telephone interviews.

RESULTS: Fifteen patients were diagnosized with DL, which account for 1.04% of the source of bleeding in acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Common comorbidities were found in one patient with hypertension and diabetic mellitus. Hemoclip or combined therapy with hemoclip produced primary hemostasis in 92.8% (13/14) of patients.

CONCLUSION: DL is uncommon but life-threatening in China. Hemoclip proved to be safe and effective in controlling bleeding from DL.

- Citation: Ding YJ, Zhao L, Liu J, Luo HS. Clinical and endoscopic analysis of gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(5): 631-635

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i5/631.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.631

Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL), an abnormal arterial lesion in the digestive tract, was first described by Gallard in 1884, then designated by George Dieulafoy in 1898 and named for this French surgeon[1]. It refers to a submucosal “caliber-persistent” artery which protrudes through a minute 2-5 mm mucosal defect, which fails to diminish to the minute size of the mucosal capillary microvasculature and becomes elongated with a diameter 10 times that of the normal arteries at the same level[2,3].

The most common and classic location of this lesion is in the proximal lesser curvature within 6 cm of the gastro-esophageal junction. However, uncommon occurrences in other sites including esophagus, duodenum, Billroth II anastomoses after gastrectomy, jejunum, colon, and rectum have also been described[3-5]. The erosion of “calliber-persistent” artery in DL may lead to massive and serious gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, which accounts for 1%-5% of the origin of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding[6-8]. Endoscopic diagnosis may be very difficult especially on the first episode due to the minute size of the lesion and the intermittent nature of the related bleeding. A wide variety of endoscopy techniques including injection of epinephrine (EPI) and sclerosing substances, heater and Argon probe coagulation, and mechanical procedures including endoscopic band ligation (EBL) and hemoclipping have been applied in the treatment of the lesion and achieve satisfactory hemostasis with low recurrence and complication rates[3-11]. However, no single modality has been proven superior to the others. The choice depends on the endoscopist’s preference and experience, as well as the clinical setting. Recently, there has been a trend suggesting that hemoclipping and EBL may be the first-line choice, while endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided angiotherapy appears to be promising[12,13].

Although studies on the management and long-term outcome of GI DL have been widely documented, gastric DL and its clinical features in Chinese patients is poorly understood. In this retrospective study, we investigate the incidence, location, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and effectiveness of endoscopy treatment on gastrointestinal DL in Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, with the aim of presenting experience on diagnosis and treatment of DL in China.

All patients who underwent emergency upper GI endoscopy due to acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding from February 2000 to August 2008 at GI endoscopy center of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University were included in this study. Diagnosis of DL was established based on the following published criteria: (1) active arterial spurting or micropulsatile streaming from a minute mucosa defect; (2) visualization of a protruding vessel with or without active bleeding within a minute mucosal defect within normal surrounding mucosa; and (3) densely adherent clot with a narrow point of attachment to a minute mucosal defect or normal appearing mucosa[6,8,12]. Hemodynamic instability was defined as meeting one or more of the following criteria: (1) systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg and pulse rate > 100 bpm; (2) orthostatic change in systolic blood pressure > 20 mmHg; and (3) decrease in hemoglobin of at least 2 g/dL in 24 h and need for blood transfusion before endoscopy.

Endoscopies were performed with Olympus videoendoscope after hemodynamic support treatment including intravenous fluids and blood transfusion if necessary. Endoscopic therapy was performed immediately after diagnosis with informed consent and the choice of endoscopy technique were decided by the endoscopist performing the procedure. Local injection was performed with an EPI solution 1:10 000 in 4-quadrant fashion. Thermocoagulation was performed with a 2.3 mm diameter heat probe (HP) set at 25-30 J/pulse. Hemoclips (MD-850, Olympus) were applied with a rotatable clip-fixing device (HX-6UR-1) by using an endoscope with a 3.2 mm diameter accessory channel. Primary hemostasis was defined as no further bleeding from the site of DL for 5 min before withdrawal of the endoscope or disappearance of the vessel. Omeprazole 40 mg twice daily was given intravenously to all patients after initial endoscopy for 5-7 d and stopped if there was no further bleeding; feeding started 3-5 d after initial endoscopy if no recurrent bleeding occurred. Recurrent bleeding was defined as hemodynamic instability due to bleeding symptoms or requirement of blood transfusions more than 5 units or decrease in hemoglobin more than 3 g/dL within 48 h associated with a fresh adherent clot or active bleeding from the same site of DL found in the initial endoscopy. Another endoscopy was performed 72 h after the initial hemostatic procedure or earlier if recurrent bleeding occurred in all patients. Angiography and gel-foam embolism were applied if it was difficult to identify the location of bleeding or achieve hemostasis after repeat endoscopy and surgery intervention was not selected by surgeon. The clinical presentation, medical history, location and characteristics of DL, methods and effectiveness of therapy of those patients were retrospectively analyzed by chart review. Long-term follow-up data were collected at outpatient clinics or by telephone interviews. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Fifteen out of 1433 patients with acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding were diagnosed as having DL from February 2000 to August 2008 at GI endoscopy center of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, which accounted for 1.04% of the sources of bleeding in acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding. The clinical presentation and endoscopy diagnosis of DL are listed in Table 1. Endoscopy treatment and outcome of DL are listed in Table 2. The median age was 36.1 years, ranging from 11-80 years. Most patients presented with melena and/or hematemesis while 1 female, an 80-year-old patient presented (patient No. 10) with only hypotension without external signs of bleeding. She had a previous history of hypertension and diabetic mellitus. No other common comorbidity causes for DL was found in other patients. No patients were receiving anticoagulant therapy, platelet aggregation inhibitors (PAI), or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs medication.

| Patient No. | Sex/age (yr) | Clinical presentation | Hemodynamic instability | Location | Stigmata (forrest) | Diagnosis at initial endoscopy |

| 1 | M/40 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Subcardinal area (remnant stomach) | Ia | + |

| 2 | M/60 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Subcardinal area | Ia | + |

| 3 | M/36 | Melena | - | Fundus | IIa | + |

| 4 | F/15 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ib | + |

| 5 | M/11 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 6 | M/20 | Hematemesis | + | Proximal corpus | Ia | + |

| 7 | F/54 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 8 | M/23 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Proximal corpus | Ia | - |

| 9 | F/43 | Melena | - | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 10 | F/80 | Hypotension | + | Fundus | IIb | - |

| 11 | M/25 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 12 | M/35 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 13 | M/25 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | - |

| 14 | M/47 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| 15 | M/28 | Melena/hematemesis | + | Fundus | Ia | + |

| Patient No. | Endoscopy treatment | Primary hemostasis | Relapse within 30 h | Treatment for relapse | Hemostasis for relapse | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | EPI + hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 22 |

| 2 | EPI + HP + hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 10 |

| 3 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 17 |

| 4 | EPI | + | - | - | - | 33 |

| 5 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 28 |

| 6 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 39 |

| 7 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 6 |

| 8 | Hemoclip | + | + | Surgery | - | 8 |

| 9 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 44 |

| 10 | - | - | + | 2nd: angiography embolism; 3th: hemoclip | + | 41 |

| 11 | Hemoclip | + | + | Angiography embolism | - | -(death) |

| 12 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 17 |

| 13 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 6 |

| 14 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 35 |

| 15 | Hemoclip | + | - | - | - | 21 |

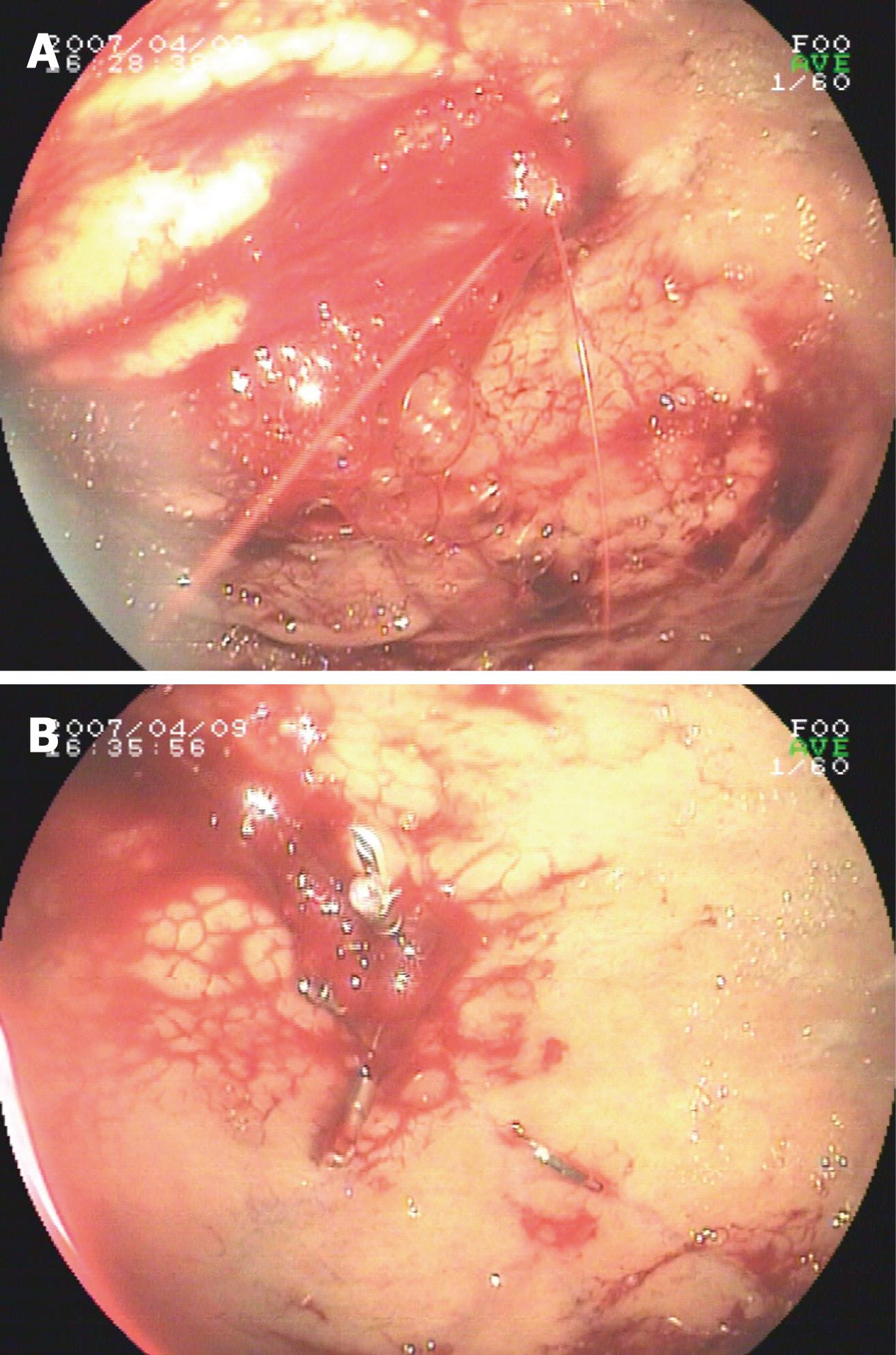

Eleven patients presented with hemodynamic instability and needed blood transfusion before endoscopy. Active bleeding was detected during first endoscopy in 13 patients. A nonbleeding visible vessel was detected in 1 patient, and a minute mucosal defect below an adherent clot was detected in 1 patient. Three patients failed to establish diagnosis of DL during first endoscopy and needed more than one endocopy to achieve conclusive diagnosis and exact location of DL. The most frequent location was the fundus (11/15, 73.3%), followed by the subcardinal area (2/15, 13.3%), and proximal corpus (2/15, 13.3%). For hemostasis, three endoscopic techniques were used: (1) only EPI in 1 case; (2) only hemoclipping in 11 cases; (3) EPI plus hemoclipping in 1 case; and (4) EPI, heat probe plus hemoclip in 1 case. Primary hemostasis was achieved in 14 patients. No endoscopic complications were found. Recurrent bleeding was detected in 3 patients (patient No. 8, 10 and 11) within 30 h. Angiography and gel-foam embolism were applied to identify location and hemostasis in patient No. 10 and No. 11 during the second bleeding. In patient No. 10, the source of bleeding was concluded to be located in the colon by angiography but colonscopy failed to identify the source of bleeding in the colon. DL in the stomach was identified by gastroscopy during the third bleeding, while hemostasis was subsequently achieved by hemoclipping. Patient 11 died of recurrent bleeding and fever 1 d after embolization. For patient No. 8, a hemoclip was placed during the second endoscopy. Subsequently, surgical intervention was selected due to uncontrolled bleeding during the third episode. Multiple DL was identified at the same site during the initial endoscopy by emergency endoscopy during the operation. Hemostasis was achieved by oversewing at the location of DL. Typical bleeding of gastric DL and hemostasis after hemoclipping are shown in Figure 1A and B.

Follow-up was conducted in 14 patients, ranging from 6 to 44 mo after effective treatment. No recurrent bleeding was noted in all patients.

In this study, we found that DL accounts for 1.04% (15/1433) of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding according to an 8 years clinical investigation in a provincial general hospital in Middle China. This proportion, consistent with other previously published epidemiological series, indicates that DL appears not to be a common source of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding in China[4,5,12,14,15]. On the other hand, 86.7% (13/15) patients with active bleeding and hemodynamic instability were diagnosed with DL, which suggests that DL should be fully recognized as a potentially severe cause of upper GI bleeding and a life-threatening GI emergency.

As some clinical and epidemiological data have previously suggested, DL usually affects elderly patients with significant comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, chronic renal failure, liver cirrhosis, neurological disease or mediation, which influence blood coagulation[1,4,5,8,12,14,16]. It has been speculated that those systemic conditions may disturb normal angiogenesis, including the formation of aberrant caliber persistent vessels, thus increasing the incidence of DL. Our data detected only 2 patients > 60 years and 1 elderly patient with significant comorbidities including hypertension and diabetic mellitus. Having relatively few comorbidities in the present study may be attributed to the much younger mean ages of patients with DL, which seems not agree with those of previous studies. However, the actual incidence of DL in elderly patients may be underestimated in that (1) Elderly patients are more reluctant to undertake emergency endoscopy; (2) Concomitant systemic conditions in elderly patients may dramatically increase the risk of emergency endoscopy and compel clinicians to give up emergency endoscopy; and (3) Systemic conditions may obscure the manifestations of DL and decrease suspicion by clinicians. For example, melena or hematemesis was persistently absent in 1 elderly patient during 3 episodes of massive GI bleeding from DL in our study, which delayed the diagnosis of DL until repeat endoscopy was performed. Similar conditions may also occur in other elderly patients with DL, leading to failure of diagnosis.

Data on the distribution of DL in the GI tract showed that the majority of DL occurs in the stomach in the upper GI tract and is located in the region within 6 cm of the gastroesophageal junction[1,6,14,16,17]. In this study, the most frequent location of DL was also found at this classic site of DL. Therefore, this site should be highly suspicious and exhaustively explored during emergency endoscopy in order to achieve an early diagnosis of DL. In our series, the first endoscopy failed to identify the location of DL in 3 patients. Failure to detect DL initially may be attributed to (1) intermittent bleeding and retracted vessels make DL invisible; (2) an excessive quantity of blood in stomach obscures the visual field; (3) alternative lesions give rise to GI bleeding already detected which prevents further detection of DL. In those special cases, repeat endoscopy is frequently necessary, and gastric lavage or position shifting may be needed for an accurate diagnosis.

Endoscopic therapy is currently advocated as a first-line choice for homeostasis of DL. A large variety of hemostasis techniques including injection of epinephrine or sclerosant, heater or Argon probe coagulation, elastic band ligation (EBL), hemoclip or a combination of those methods have been used for hemostasis of DL with permanent hemostasis achieved in more than 90% of patients[1,4-9,14-16,18-20]. Up to now, it has not been concluded that one single therapeutic modality is superior to another in well designed retrospective or randomized controlled trials[10,15,18]. The choice of technique should be individualized for each patient and depend on the type and location of DL, endoscopist’s experience and competency, and the risk and complication of techniques. In the present study, hemoclip or combined therapy of EPI or HP followed by hemoclip achieved primary hemostasis in 92.8% (13/14) of patients. Recurrent bleeding occurred in only 1 patient with multiple DL during the second endoscopy. No recurrent bleeding occurred in long-term follow-up, demonstrating that the hemoclip is effective and safe for controlling bleeding from DL. According to our experience, hemoclipping has a special advantage in that (1) it is easier to perform technically than other techniques like EBL or sclerosis; (2) it causes less damage to the surrounding tissues, thus avoiding the possibility of necrosis or perforation caused by sclerosant injection or thermal coagulation; (3) it is effective for proximal gastric lesions with protruding vessels or active bleeding; and (4) it is an easy and safe method for controlling recurrent bleeding. Additionally, we found that use of EPI or HP before application of the hemoclip may achieve a better visual field in cases with profound bleeding, which will facilitate the application of the hemoclip.

Angiography and gel-foam embolism were applied to identify the location and hemostasis of DL in 2 patients with recurrent bleeding in our study. Bleeding from the colon as a false-positive result was concluded in 1 patient and death due to fever and profound bleeding immediately after gel-foam embolism occurred in another patient. Therefore, the accuracy and risk of this technique should be fully evaluated when choosing treatment for DL bleeding. Furthermore, bleeding from multiple DL was found in 1 patient during recurrent episodes of bleeding, which were controlled by surgical oversewing. Further explanation for this phenomenon is needed.

In conclusion, DL, as an uncommon cause, accounts for 1.04% of the instances of non-variceal upper GI bleeding in Middle China. Hemoclipping proved to be safe and effective in controlling bleeding from DL. Further investigations are needed to accumulate more experience on endoscopic treatment for elderly patients with DL. Better options and approaches should be explored for identifying the location of DL which are difficult to define and refractory to routine endoscopy techniques.

Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) refers to submucosal “caliber-persistent” artery which fails to diminish to the minute size of the mucosal capillary microvasculature and becomes elongated with a diameter 10 times that of the normal arteries at the same level. The erosion of “caliber-persistent” arteries in DL may lead to massive and serious gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, which accounts for 1%-5% of the origin of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Endoscopy diagnosis may be very difficult especially on the first episode due to the minute size of the lesion and the intermittent nature of the related bleeding.

Endoscopy diagnosis may be very difficult especially on the first episode due to the minute size of the lesion and the intermittent nature of the related bleeding. A wide variety of endoscopy techniques including injection of epinephrine and sclerosing substances, heater and Argon probe coagulation, and mechanical procedures including endoscopic band ligation and hemoclipping have been applied in the treatment of the lesion and achieve satisfactory hemostasis with a low recurrence and complication rate. However, no single modality has been proven superior to the others.

This study investigated the incidence, location, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion in a Chinese region and evaluated the options and effectiveness of endoscopic treatment for DL.

This study indicated that DL is an uncommon cause of non-variceal upper GI bleeding in Middle China. Hemoclipping proved to be safe and effective in controlling bleeding from DL. Those results provide a background for further investigation for better options and approaches.

In the method section, the trends of selected endoscopic methods in the hospital should be described during the 8 years’ study period, because almost all cases were treated by hemoclips.

Peer reviewer: Mitsuhiro Fujishiro, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Endoscopy and Endoscopic Surgery, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor O'Neill M E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Lee YT, Walmsley RS, Leong RW, Sung JJ. Dieulafoy's lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:236-243. |

| 2. | Juler GL, Labitzke HG, Lamb R, Allen R. The pathogenesis of Dieulafoy's gastric erosion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:195-200. |

| 3. | Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Bartelsman JF, Schipper ME, Tytgat GN. Recurrent massive haematemesis from Dieulafoy vascular malformations--a review of 101 cases. Gut. 1986;27:213-222. |

| 4. | Baettig B, Haecki W, Lammer F, Jost R. Dieulafoy's disease: endoscopic treatment and follow up. Gut. 1993;34:1418-1421. |

| 5. | Norton ID, Petersen BT, Sorbi D, Balm RK, Alexander GL, Gostout CJ. Management and long-term prognosis of Dieulafoy lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:762-767. |

| 6. | Sone Y, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Hisanaga Y, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M. Endoscopic management and follow up of Dieulafoy lesion in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2005;37:449-453. |

| 7. | Romãozinho JM, Pontes JM, Lérias C, Ferreira M, Freitas D. Dieulafoy's lesion: management and long-term outcome. Endoscopy. 2004;36:416-420. |

| 8. | Nikolaidis N, Zezos P, Giouleme O, Budas K, Marakis G, Paroutoglou G, Eugenidis N. Endoscopic band ligation of Dieulafoy-like lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2001;33:754-760. |

| 9. | Park CH, Sohn YH, Lee WS, Joo YE, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim SJ. The usefulness of endoscopic hemoclipping for bleeding Dieulafoy lesions. Endoscopy. 2003;35:388-392. |

| 10. | Iacopini F, Petruzziello L, Marchese M, Larghi A, Spada C, Familiari P, Tringali A, Riccioni ME, Gabbrielli A, Costamagna G. Hemostasis of Dieulafoy's lesions by argon plasma coagulation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:20-26. |

| 11. | Nagri S, Anand S, Arya Y. Clinical presentation and endoscopic management of Dieulafoy's lesions in an urban community hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4333-4335. |

| 12. | Ibáñez A, Castro E, Fernández E, Baltar R, Vázquez S, Ulla JL, Alvarez V, Soto S, Barrio J, Carpio D. [Clinical aspects and endoscopic management of gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy's lesion]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:505-510. |

| 13. | Levy MJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Farnell MB, Misra S, Sarr MG, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided angiotherapy of refractory gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:352-359. |

| 14. | Yamaguchi Y, Yamato T, Katsumi N, Imao Y, Aoki K, Morita Y, Miura M, Morozumi K, Ishida H, Takahashi S. Short-term and long-term benefits of endoscopic hemoclip application for Dieulafoy's lesion in the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:653-656. |

| 15. | Kasapidis P, Georgopoulos P, Delis V, Balatsos V, Konstantinidis A, Skandalis N. Endoscopic management and long-term follow-up of Dieulafoy's lesions in the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:527-531. |

| 16. | Schmulewitz N, Baillie J. Dieulafoy lesions: a review of 6 years of experience at a tertiary referral center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1688-1694. |

| 17. | Scheider DM, Barthel JS, King PD, Beale GD. Dieulafoy-like lesion of the distal esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2080-2081. |

| 18. | Skok P. Endoscopic hemostasis in exulceratio simplex-Dieulafoy's disease hemorrhage: a review of 25 cases. Endoscopy. 1998;30:590-594. |

| 19. | Stark ME, Gostout CJ, Balm RK. Clinical features and endoscopic management of Dieulafoy's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:545-550. |

| 20. | Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ, Cho MS. Bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and the choice of endoscopic method: comparing the hemostatic efficacy of mechanical and injection methods. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:721-724. |