Published online Jan 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.522

Revised: December 14, 2009

Accepted: December 21, 2009

Published online: January 28, 2010

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasia and currently well recognized as a distinct entity with characteristic morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular findings. We report a case of PEComa arising in the antrum of a 71-year-old female with melena. The tumor, located predominantly in the submucosa as a well delimited nodule, measured 3.0 cm in diameter and was completely resected, with no evidence of the disease elsewhere. Histologically, it was composed predominantly of eosinophilic epithelioid cells arranged in small nests commonly related to variably sized vessels, with abundant extracellular material, moderate nuclear variation and discrete mitotic activity. No necrosis, angiolymphatic invasion or perineural infiltration was seen. Tumor cells were uniformly positive for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, desmin and melan A. Although unusual, PEComa should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric neoplasia with characteristic epithelioid and oncocytic features and prominent vasculature.

- Citation: Mitteldorf CATDS, Birolini D, Camara-Lopes LHD. A perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the stomach: An unsuspected diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(4): 522-525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i4/522.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.522

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a mesenchymal neoplasia composed of perivascular epithelioid cells, with characteristic morphologic and immunohistochemical distinctive features[1]. It belongs to a heterogeneous family of tumors and genetic alterations have been related to cases associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)[1-3]. PEComa has been described in numerous locations, especially digestive system and uterus[1-3], but rarely in gastrointestinal tract[4-13]. We present a case of PEComa of the stomach, a site of origin not previously reported.

A 71-year-old female was admitted to our emergency room due to a recent episode of melena, referring previous similar occurrences. She had a past history of multiple laparotomies for colonic diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis and associated complications. On admission, an upper endoscopy revealed elevated gastric antral mucosa with ulceration, probably due to a submucosal lesion. A biopsy did not represent the tumor. A colonoscopy showed only diverticular disease without signs of hemorrhage or inflammation. The patient underwent a partial gastrectomy with complete resection of the lesion, during which no lymph node or peritoneal metastasis was found. After histopathological diagnosis, the patient was scanned for systemic disease, including a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), but nothing was found. She recovered well and was discharged 7 d after operation.

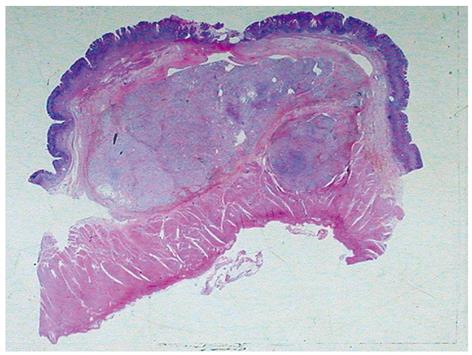

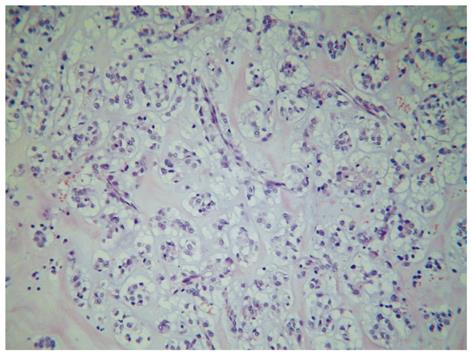

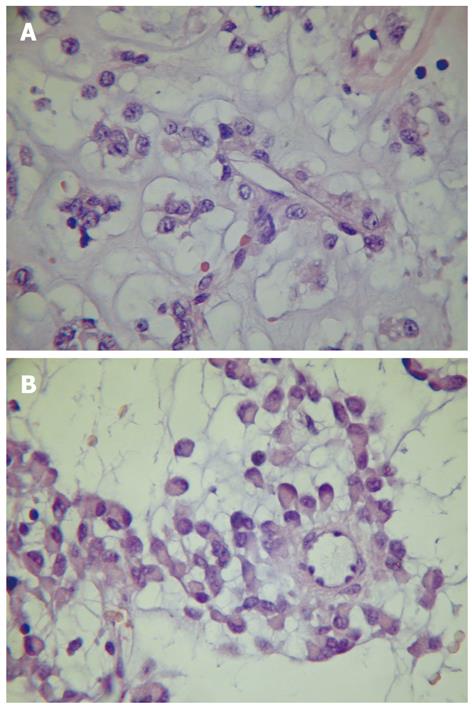

Specimen showed a predominant submucosal nodule, with focal extension to the muscularis propria. The lesion caused a discrete elevation of the adjacent mucosa with focal ulceration (Figure 1). The tumor measured 3.0 cm × 2.8 cm × 1.6 cm. Microscopic examination revealed a well-circumscribed but not encapsulated lesion. The cells were mostly arranged as small nests commonly related to variably sized vessels, with abundant extracellular material and mucinous or collagenous characteristics (Figure 2). Pseudoalveolar and focal fusocellular pattern was observed in some areas. The neoplasia was predominantly composed of eosinophilic and clear epithelioid cells (Figure 3A), also presenting focal rhabdoid features (Figure 3B). Moderate nuclear variation and discrete mitotic activity (1 mitosis/50 HPF) were observed, but there were no necrosis, angiolymphatic invasion or perineural infiltration. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, desmin, melan A, and for CD56, but negative for pan-cytokeratin AE1/AE3, chromogranin A, CD34, CD31, CD117, S100 protein, muscle specific actin HHF-35 and HMB-45.

PEComa is a rare tumor, resulting from the proliferation of PEC. There is a female predominance with a wide age distribution. The tumor has been described in numerous locations outside the kidney, but not in the stomach. It was reported that the findings of a conventional angiomyolipoma of the stomach, presented as a submucosal lesion, are similar to those of its renal counterpart[14]. Only 13 cases of PEComa, primarily located in the gastrointestinal tract, have been reported, including 3 in the small bowel, 5 in the colon, 1 in the appendix and 4 in the rectum[1-13]. All these cases were females, except for a 12-year-old boy with a past history of cervical neuroblastoma, probably related to TSC[10]. The age of these patients ranged 6-63 years, with an average age of 29 years, and the greatest tumor size varied from 1.3 to 10.0 cm. Interestingly, all the four reported cases of gastrointestinal angiomyolipoma were males, with their age ranged 55-67 years (average age of 59 years), and smaller tumors (2 in the colon, 1 in the stomach, and 1 in the rectum, measuring 1.0-3.0 cm in diameter[14-17].

PEComa is characterized by perivascular location, and the tumor cells have mostly epithelioid and spindle appearance, with clear to lightly granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. The PEC is positive for melanocytic and muscle markers[1]. The pathological findings in our case were very consistent with those of PEComa and immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis.

In PEComa, the most sensitive melanocytic markers are HMB-45, Melan-A and microphthalmia transcription factor[1]. Although our experience is limited, in part due to the rarity of the disease, we have seen other cases which were weakly and even dubiously positive for HMB-45, but strongly and uniformly positive for melan A. Now, we routinely include a panel of at least three melanocytic markers to better characterize this entity.

The main differential diagnosis includes gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), smooth muscle tumor, metastatic melanoma and endocrine neoplasia. GIST is the most common primary mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but rarely shows oncocytic or rhabdoid morphology, clear cell features or pleomorphism. On the other hand, PEComa may mimic GIST when it contains fusocellular arrangement or expressing CD117. The morphology of leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma may be very similar to that of PEComa. Some of the cases diagnosed in the past as smooth muscle tumor may indeed represent PEComas. Immunohistochemical analysis is the only way to establish the diagnosis of PEComa. Metastatic melanoma should always be considered, especially with diffuse expression of melanocytic markers. Our case was negative for S100 protein and HMB-45, but strongly and uniformly positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Some cases, however, may not present with such a characteristic profile. The distribution of these positive substances may be useful in the differential diagnosis. Most gastric endocrine neoplasms are represented by well-differentiated tumors or carcinoids, but small and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas may infrequently occur. Adenocarcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation, and mixed tumors with glandular and endocrine features have been reported. We included epithelial and neuroendocrine markers in our panel to consider these possibilities.

Ultrastructural findings, like abundant cytoplasmic glycogen, pre-melanosomes, thin filaments with occasional dense bodies, hemidesmosomes and poorly-formed intercellular junctions[1], would help to define the lineage or origin of these peculiar cells, but we do not routinely perform ultrastructural analysis in our laboratory.

The criteria of malignancy for PEComa have not been well established. WHO guidelines based on the data from well-documented malignant PEComas, suggest that PEComas should be regarded as malignant when they display infiltrative growth, marked hypercellularity, nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, high mitotic activity, atypical mitotic figures and coagulative necrosis[1]. More recently it has been reported that tumor size over 5 cm, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade, necrosis and mitotic activity over 1/50 HPF is significantly associated with aggressive clinical behavior of PEComas of soft tissue and gynecologic origin[3,7,13].

Optimal treatment of PEComas is not well established. Currently, surgery is the main treatment modality for primary tumor, local recurrence and metastasis[18]. It is obviously difficult to perform therapeutic trials, but perhaps in the near future new specific targeted therapy may be used in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, when chemotherapy and immunotherapy are considered. The present case was treated exclusively with surgical resection and the patient was well, free of disease after 19 mo.

In conclusion, gastric PEComa, as an isolated lesion, is presented with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, without evidence of the disease elsewhere. Although unusual, PEComa should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric neoplasia with characteristic epithelioid and oncocytic features and prominent vasculature.

Peer reviewer: Jae J Kim, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 50, Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 135-710, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Folpe AL. Neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas). World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 221-222. |

| 2. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. PEComa: what do we know so far? Histopathology. 2006;48:75-82. |

| 3. | Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:119-132. |

| 4. | Agaimy A, Wünsch PH. Perivascular epithelioid cell sarcoma (malignant PEComa) of the ileum. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:37-41. |

| 5. | Baek JH, Chung MG, Jung DH, Oh JH. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) in the transverse colon of an adolescent: a case report. Tumori. 2007;93:106-108. |

| 6. | Birkhaeuser F, Ackermann C, Flueckiger T, Guenin MO, Kern B, Tondelli P, Peterli R. First description of a PEComa (perivascular epithelioid cell tumor) of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1734-1737. |

| 7. | Bonetti F, Martignoni G, Colato C, Manfrin E, Gambacorta M, Faleri M, Bacchi C, Sin VC, Wong NL, Coady M. Abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelioid cells. Report of four cases in young women, one with tuberous sclerosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:563-568. |

| 8. | Evert M, Wardelmann E, Nestler G, Schulz HU, Roessner A, Röcken C. Abdominopelvic perivascular epithelioid cell sarcoma (malignant PEComa) mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the rectum. Histopathology. 2005;46:115-117. |

| 9. | Genevay M, Mc Kee T, Zimmer G, Cathomas G, Guillou L. Digestive PEComas: a solution when the diagnosis fails to “fit”. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2004;8:367-372. |

| 10. | Mhanna T, Ranchere-Vince D, Hervieu V, Tardieu D, Scoazec JY, Partensky C. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor (PEComa) of the duodenum in a child with a history of neuroblastoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1484-1486. |

| 11. | Prasad ML, Keating JP, Teoh HH, McCarthy SW, Battifora H, Wasef E, Rosai J. Pleomorphic Angiomyolipoma of Digestive Tract: A Heretofore Unrecognized Entity. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:67-72. |

| 12. | Tazelaar HD, Batts KP, Srigley JR. Primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor (PEST): a report of four cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:615-622. |

| 13. | Yanai H, Matsuura H, Sonobe H, Shiozaki S, Kawabata K. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the jejunum. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:47-50. |

| 14. | Helwig K, Talabiska D, Cera P, Komar M. Gastric angiomyolipoma: a previously undescribed cause of upper GI hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1004-1005. |

| 15. | Hikasa Y, Narabayashi T, Yamamura M, Fukuda Y, Tanida N, Tamura K, Ohno T, Shimoyama T, Nishigami T. Angiomyolipoma of the colon: a new entity in colonic polypoid lesions. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1989;24:407-409. |

| 16. | Maesawa C, Tamura G, Sawada H, Kamioki S, Nakajima Y, Satodate R. Angiomyolipoma arising in the colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1852-1854. |

| 17. | Maluf H, Dieckgraefe B. Angiomyolipoma of the large intestine: report of a case. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1132-1136. |

| 18. | Armah HB, Parwani AV. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the uterus with late renal and pulmonary metastases: a case report with review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:45. |