Published online Jun 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i23.2889

Revised: February 20, 2010

Accepted: February 27, 2010

Published online: June 21, 2010

AIM: To test whether colchicine would be an effective antifibrotic agent for treatment of chronic liver diseases in patients who could not be treated with α-interferon.

METHODS: Seventy-four patients (46 males, 28 females) aged 40-66 years (mean 53 ± 13 years) participated in the study. The patients were affected by chronic liver diseases with cirrhosis which was proven histologically (n = 58); by chronic active hepatitis C (n = 4), chronic active hepatitis B (n = 2), and chronic persistent hepatitis C (n = 6). In the four patients lacking histology, cirrhosis was diagnosed from anamnesis, serum laboratory tests, esophageal varices and ascites. Patients were assigned to colchicine (1 mg/d) or standard treatment as control in a randomized, double-blind trial, and followed for 4.4 years with clinical and laboratory evaluation.

RESULTS: Survival at the end of the study was 94.6% in the colchicine group and 78.4% in the control group (P = 0.001). Serum N-terminal peptide of type III procollagen levels fell from 34.0 to 18.3 ng/mL (P = 0.0001), and pseudocholinesterase levels rose from 4.900 to 5.610 mU/mL (P = 0.0001) in the colchicine group, while no significant change was seen in controls. Best results were obtained in patients with chronic hepatitis C and in alcoholic cirrhotics.

CONCLUSION: Colchicine is an effective and safe antifibrotic drug for long-term treatment of chronic liver disease in which fibrosis progresses towards cirrhosis.

- Citation: Muntoni S, Rojkind M, Muntoni S. Colchicine reduces procollagen III and increases pseudocholinesterase in chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(23): 2889-2894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i23/2889.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i23.2889

Hepatic fibrosis results from excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components, namely fibril-forming collagen type I and III. Fibrosis and cirrhosis develop after chronic injury from many causes, including persistent viral and helminthic infections, alcohol, autoimmune hepatitis, and metal overload. Early stages of fibrosis are reversible either by removal of the specific stimulus or by treatment with antifibrotic medications, whereas late stages, progressing to cirrhosis, are less reversible[1,2].

Our current knowledge of the pathology of hepatic stellate cells (HSC), the main producers of type I collagen in the liver, as well as the molecular mechanisms involved in the activation of HSC and collagen production, have resulted in the discovery of new sites for potential therapeutic intervention. Among the various medical treatments, colchicine is a safe and efficient drug, based on our current knowledge of its pharmacodynamic[3-5], pharmacokinetic[6] and therapeutic[7-11] properties, and its ability to prevent or delay the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in viral-related liver cirrhosis[12].

In this communication we present our findings after 4.4 years of follow up of a group of 74 patients who were randomly assigned to colchicine or control treatment. Our results show that colchicine treatment decreased mortality and significantly lowered serum levels of type III procollagen peptide (P-III-P) as compared with the control group.

Seventy-four patients (46 males and 28 females) aged 40-66 years (mean 53 ± 13 years) participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were on an intention-to-treat basis. Exclusion criteria were: age < 20 years or a known hypersensitivity to colchicine. Patients were recruited by referral from general practitioner or by self choice and gave informed consent to be assigned to intervention (colchicine) or control by using random allocation. Randomization was performed by giving 74 consecutive numbers to all patients coming to our clinic between the years 2000 and 2003. Both the intervention group (group A) and the control group (group B) consisted of 37 patients. Group A was treated with colchicine (1 mg/d per os). Group B received the usual treatment for cirrhosis (diuretics, β-blockers, ursodeoxycholic acid, withdrawal of alcohol). Sixty-two patients were affected by different chronic liver diseases + cirrhosis (CLD + C), which was proven histologically in 58 of them (93.5%). In the four patients lacking histology, cirrhosis was diagnosed from serum laboratory tests, esophageal varices and ascites, consistent with clinical history. Twenty-eight patients (15 in group A, and 13 in group B) had post-hepatitis C cirrhosis (12 had been previously treated unsuccessfully with α-interferon for 12 mo), 20 patients (9 and 11 in each group, respectively) had post-hepatitis B cirrhosis, 10 (5 and 5) alcoholic cirrhosis, 4 (2 and 2) primary biliary cirrhosis. Among the 12 patients in whom cirrhosis was not found, 4 patients (2 and 2 in each group, respectively) had chronic active hepatitis C, 2 (1 and 1) chronic active hepatitis B, and 6 (3 and 3) chronic persistent hepatitis C (Table 1). Reasons for excluding the use of α-interferon for post-hepatitis C cirrhosis were: (1) previous unsuccessful treatment; (2) withdrawal owing to severe side effects; (3) autoimmune disorders; (4) severe depression; (5) thrombocytopenia; (6) decompensated cirrhosis; and (7) refusal. For these reasons the involvement of an Ethical Committee was thought not necessary. The study protocol conforms, however, to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The patients were followed up for a mean of 4.4 years, from 2000 to 2007, at the Centre for Metabolic Diseases and Atherosclerosis of Cagliari, Italy. During the study ten died (3 in group A and 7 in group B) and 12 (9 in group A and 3 in group B) withdrew from the study due to personal reasons.

| Disease | Group A | Group B | P |

| Post-hepatitis C cirrhosis | 15 | 13 | 0.65 |

| Post-hepatitis B cirrhosis | 9 | 11 | 0.65 |

| Chronic active hepatitis C | 2 | 2 | 0.70 |

| Chronic active hepatitis B | 1 | 1 | 0.85 |

| Chronic persistent hepatitis C | 3 | 3 | 0.85 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 5 | 5 | 0.90 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 | 2 | 0.80 |

| Total | 37 | 37 |

The liver function tests performed every year (half year initially) were: aminotransferases (mU/mL, normal values < 40), prothrombin time (%, normal values 70-100), pseudocholinesterase (mU/mL, normal values 5600-13 000), albumin (g/dL, normal values 3.5-5.0) and globulins (g/dL, normal values 0.6-1.0) displayed as an electrophoretogram. Serum N-terminal peptide of type III procollagen (P-III-P) was determined by radioimmunoassay, using the Cobra γ-counter device (ng/mL, normal values 4-14), as a marker of fibrogenesis in place of liver biopsy during follow-up[13].

Survival curves were plotted with the use of the Kaplan-Meier approach[14]. Differences in cumulative survival between the colchicine and the control groups were analyzed by means of the log-rank test[15]. Paired t-test of liver function tests between groups A and B, and in the same groups between baseline and 4-year values was performed. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated through interval estimation. Factor analysis for reducing individual scores from many to three was used[16] when analyzing the treatment outcome in patients with chronic liver disease C and in alcoholic cirrhosis using the following three criteria: serum levels of P-III-P and γ globulins; serum pseudocholinesterase and albumin; subjective state of health.

Colchicine treatment was well tolerated, with transient diarrhea in a few cases. Overall, the best results obtained after 4 years of colchicine treatment were in subjects with chronic hepatitis C (20 cases, P = 0.001). In post-hepatitis B cirrhosis the results were less favourable and 2 of the 9 initial patients died before the 4th year. Nonetheless, in the remaining 7 patients a good result was obtained (P = 0.05 vs controls) (Table 2).

| Number of cases | Number of improved | P vs controls | |

| Post-hepatitis C cirrhosis | 15 | 13 | 0.001 |

| Post-hepatitis B cirrhosis | 9 | 11 | 0.05 |

| Chronic active hepatitis C | 2 | 2 | 0.001 |

| Chronic active hepatitis B | 1 | 1 | 0.50 |

| Chronic persistent hepatitis C | 3 | 3 | 0.001 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 5 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 | 2 | 0.55 |

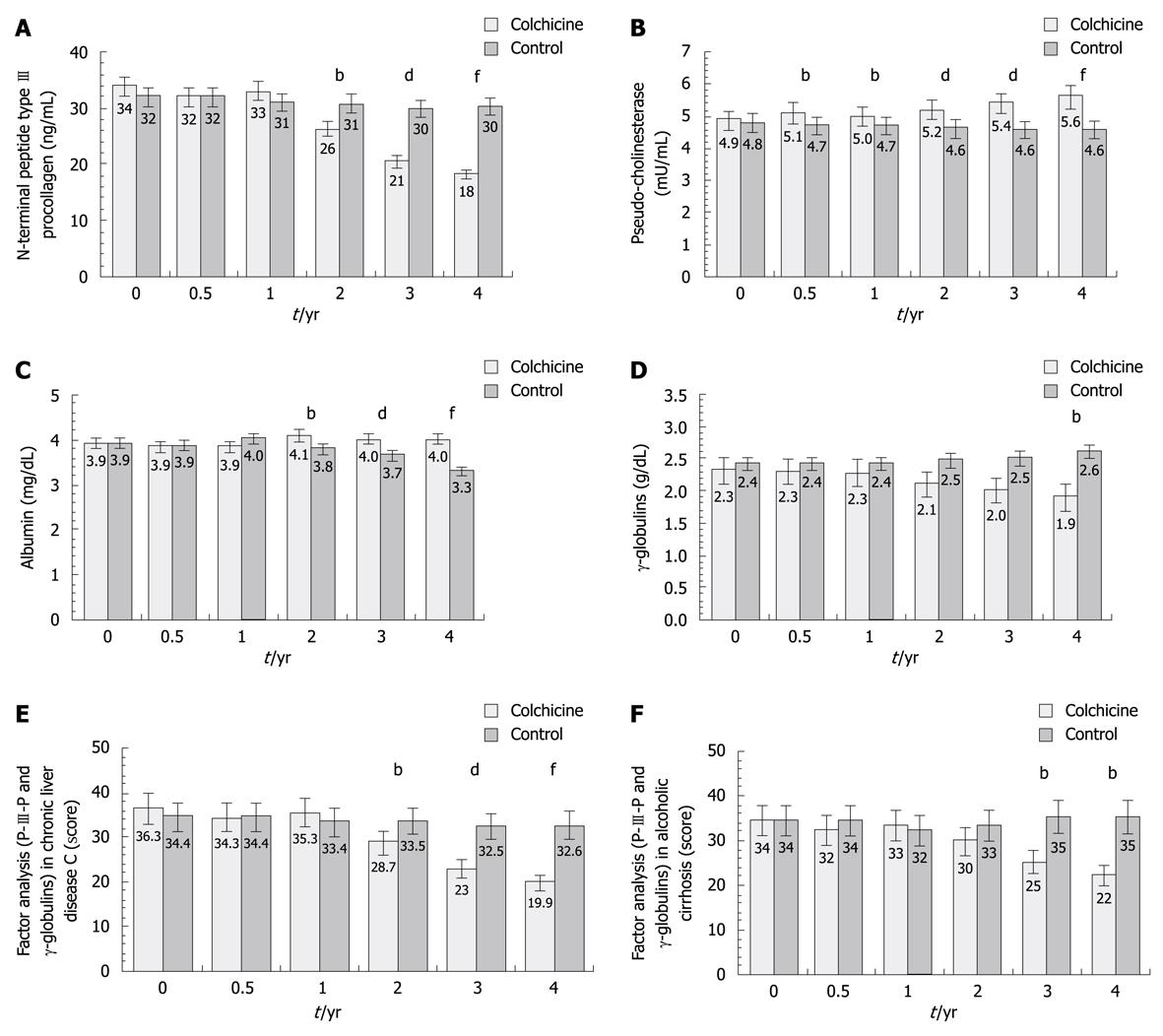

Liver test values at baseline, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 years in the 37 patients treated with colchicine vs the 37 controls are reported in Table 3 and in Figure 1. In the colchicine group the most striking improvement was in serum P-III-P values, which steadily declined from 34.0 at baseline to 26.2 at 2 years (-22.9%) and to 18.3 at 4 years (-46.2% from 34.0% to 18.3%, P < 0.0001, 95% CI: 19.4-17.1) (Table 3 and Figure 1A), and for pseudocholinesterase, the activity of which rose from 4900 at baseline to 5200 at 2 years (+6.1%) and to 5610 at 4 years (+14.5%, P < 0.0001, 95% CI: 5.7-5.5) (Table 3 and Figure 1B). These results are in striking contrast with the control group in which P-III-P serum levels and pseudocholinesterase did not change significantly. Serum albumin and γ globulin levels also improved in the colchicine as compared with the control group (P < 0.0001, 4.1 to 3.9 and 2.2 to 1.5, respectively) (Figure 1C and D).

| Group A | % | P | Group B | % | P | |

| P-III-P baseline (ng/mL) | 34.0 | 32.0 | ||||

| P-III-P 2 yr (ng/mL) | 26.2 | -22.9 | 0.01 | 30.8 | -3.7 | 0.6 |

| P-III-P 4 yr (ng/mL) | 18.3 | -46.2 | < 0.0001 | 30.2 | -5.6 | 0.5 |

| Pseudocholinesterase baseline (mU/mL) | 4900 | 4800 | ||||

| Pseudocholinesterase 2 yr (mU/mL) | 5200 | +6.1 | 0.05 | 4620 | -3.7 | 0.6 |

| Pseudocholinesterase 4 yr (mU/mL) | 5610 | +14.5 | < 0.001 | 4580 | -4.6 | 0.6 |

Survival of the 74 patients is reported in Table 4. Of the 37 patients in group A (colchicine), 36 survived at 2 years and 34 at 4 years. Of the 37 patients in group B (control), 35 survived at 2 years and 30 at 4 years. The survival figures showed a statistically significant benefit of colchicine (P = 0.001). The cumulative 4-year survival rate was 91.9% in group A and 81.1% in group B.

| Group A | Group B | P | |

| Baseline | 37 | 37 | |

| 2 yr | 36 (97.3) | 35 (94.6) | 0.05 |

| 4 yr | 34 (91.9) | 30 (81.1) | 0.001 |

The complications of cirrhosis are reported in Table 5: ascites, encephalopathy and esophageal hemorrhage were almost absent in group A (2 esophageal hemorrhages vs 10 in group B, P < 0.001).

| Complications | Group A | Group B | P |

| Ascites | 0 | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| Esophageal hemorrhage | 2 | 10 | < 0.001 |

The factor analysis of serum P-III-P and γ globulin levels in chronic hepatitis C showed a statistically significant improvement at 2, 3 and 4 years in the colchicine group (Figure 1E). In patients with alcoholic cirrhosis a significant change in the above parameters was reached at 3 and 4 years of colchicine treatment (Figure 1F). In contrast with these findings, a significant improvement in cholinesterase and albumin were observed until year 4 in chronic hepatitis C, while in alcoholic cirrhotic patients a statistically significant difference was found at 3 and 4 years of colchicine therapy. Regarding the overall subjective evaluation of colchicine patients with chronic hepatitis C and with alcoholic cirrhosis, a statistically significant difference, compared to controls, was found at 2, 3 and 4 years.

The striking improvement of CLD + C patients treated with colchicine, as compared with those on standard treatment, shows the effectiveness of colchicine for the treatment of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis[7-11]. Because this study was not designed to investigate a potential antiviral effect of colchicine, changes in viral DNA in patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) were not investigated. Nonetheless, an antiviral effect of colchicine has been already documented by Floreani et al[9].

In the colchicine group, 9 patients stopped the treatment, vs only 3 patients in the control group, thus revealing a lower compliance with colchicine.

Multiple studies using colchicine for the treatment of chronic liver disease of different etiologies have shown variable results. In one study of hepatitis B patients, colchicine administered 5 mg/wk for 4 years showed a preventive effect towards evolution to cirrhosis (32.0% in treatment group A vs 73.2% in control group B), although of borderline significance[17].

In a study of hepatitis C, the combination of colchicine plus interferon resulted in worsening of alanine transaminase values and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA levels compared to patients receiving only interferon[18].

In alcoholic cirrhosis treated with colchicine for up to 6 years, overall liver specific mortality was not reduced; however the alcoholic cirrhosis was advanced and, moreover, fewer patients on colchicine developed hepatorenal syndrome. The authors concluded that colchicine is not recommended for advanced cirrhosis[19], in agreement with Tome et al[20].

In primary biliary cirrhosis, where colchicine is indicated[4,7], the addition of colchicine to ursodeoxycholic acid was shown to result in a small but significant reduction in disease progression[21].

In addition to already cited papers[8,11], colchicine has been found to prevent the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in virally-related liver cirrhosis. However, the differences were not statistically significant when compared with a group receiving peginterferon (7.7% in interferon group and 5.9% in colchicine group (P = 0.5). The drug was less active than peginterferon alfa-2b in preventing variceal bleeding[22]. In 116 patients with virally-related liver cirrhosis on treatment with colchicine for a minimum of 3 years, hepatocellular carcinoma was prevented or delayed, compared with controls (9.0% vs 29.0%, P = 0.01), possibly through its anti-inflammatory effect[12].

In a study of 100 patients with various types of liver cirrhosis, colchicine was markedly better than control treatment as far as 10 years survival rates (56% vs 20%) and improvement of liver biopsies were concerned[23].

In another study in which the authors analyzed the combined results of 14 randomized clinical trials totalling 1138 patients, they concluded that colchicine should not be used for liver fibrosis or cirrhosis of various etiologies[24].

A study of the effect of colchicine combined with radiation showed that low doses of the drug possess radiosensitizing effects for HCC treatment[25].

Overall, our findings suggest that colchicine is antifibrogenic based on the significant decrease in the levels of serum P-III-P, a peptide derived from the processing of newly synthesized type III collagen, an important component of liver scar tissue. This parameter has been used by others as a non-invasive procedure to follow liver fibrosis[13]. Thus, our findings together with the results obtained by Kershenobich et al[7] and other authors[8-11] clearly show that colchicine is effective for the treatment of some forms of liver cirrhosis. In this communication we report a significant improvement in patients with HCV who for various reasons declined to continue the use of interferon therapy. In the publication by Kershenobich et al[7] a significant improvement in patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis treated with colchicine was reported. Based on these findings it is possible to suggest that a better selection of patients, such as subjects with HCV who do not respond to interferon therapy, and early intervention could benefit a large population of patients for whom there is no alternative therapy.

In this study of patients with CLD + C, colchicine produced a clear-cut antifibrogenic effect, as indicated by the progressive decrease of serum P-III-P and the parallel improvement of liver function tests.

Colchicine is an effective and safe antifibrotic drug for long-term treatment of chronic liver disease in which fibrosis progresses towards cirrhosis. It was shown not only to arrest, but even to reverse this process. With regard to the arrest of fibrosis, the stage of the disease at which colchicine treatment must be started is probably earlier than suggested at the present time. This does not mean that the drug provides an alternative to other well-established therapeutic strategies, but rather that colchicine should find its placement in association with the latter, except for combination with α-interferon in hepatitis C, where it displays unfavourable effects[18]. Removal of the initiating factor(s) is the best way, when feasible, to prevent the progression of hepatic disease[1,2]. With the addition of colchicine, this approach could be even more effective. Moreover, since liver cirrhosis is reversible[2,26], colchicine should be considered as a therapeutic agent. Histological evidence in addition to clinical non-invasive parameters could help in determining the antifibrogenic properties of colchicine. Accordingly, clinical trials of colchicine treatment in early stages of chronic liver disease are warranted.

Fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver develop as a response to chronic injury from many causes. Early stages of fibrosis are reversible by treatment with antifibrotic drugs.

Hepatic stellate cells provide a new site for potential therapeutic intervention with colchicine, which, besides its antifibrotic properties, can prevent or delay hepatocellular carcinoma.

There was a statistically significant survival benefit in the colchicine group, in which complications were almost absent. The plasma levels of P-III-P declined progressively only in the colchicine group. The authors concluded that colchicine is an effective and safe antifibrotic drug.

Fibrosis and cirrhosis develop after persistent viral and helminthic infections, alcohol abuse, autoimmune hepatitis or metal overload. Serum N-terminal peptide of type III collagen (P-III-P) is a marker of fibrogenesis, that can be exploited in place of liver biopsy. Plasma pseudocholinesterase and albumin can be measured as a response to P-III-P.

The article presents evidence for a drug, colchicine, which could prevent progression of liver disease.

Peer reviewer: Maria Concepción Gutiérrez-Ruiz, PhD, Department of Health Sciences, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, DCBS, Av San Rafael Atlixco 186, Colonia Vicentina, México, DF 09340, Mexico

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Friedman SL. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. The cellular basis of hepatic fibrosis. Mechanisms and treatment strategies. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1828-1835. |

| 2. | Rockey DC. Antifibrotic therapy in chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:95-107. |

| 3. | Gemsa D, Kramer W, Brenner M, Till G, Resch K. Induction of prostaglandin E release from macrophages by colchicine. J Immunol. 1980;124:376-380. |

| 4. | Gordon S, Werb Z. Secretion of macrophage neutral proteinase is enhanced by colchicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:872-876. |

| 5. | Kershenobich D, Rojkind M, Quiroga A, Alcocer-Varela J. Effect of colchicine on lymphocyte and monocyte function and its relation to fibroblast proliferation in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1990;11:205-209. |

| 6. | Chappey ON, Niel E, Wautier JL, Hung PP, Dervichian M, Cattan D, Scherrmann JM. Colchicine disposition in human leukocytes after single and multiple oral administration. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:360-367. |

| 7. | Kershenobich D, Vargas F, Garcia-Tsao G, Perez Tamayo R, Gent M, Rojkind M. Colchicine in the treatment of cirrhosis of the liver. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1709-1713. |

| 8. | Kaplan MM, DeLellis RA, Wolfe HJ. Sustained biochemical and histologic remission of primary biliary cirrhosis in response to medical treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:682-688. |

| 9. | Floreani A, Lobello S, Brunetto M, Aneloni V, Chiaramonte M. Colchicine in chronic hepatitis B: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:653-656. |

| 10. | Adhami JE, Basho J. Treatment with colchicine and survival of patients with ascitic cirrhosis: a double-blind randomized trial. Panminerva Med. 1998;40:75-81. |

| 11. | Nikolaidis N, Kountouras J, Giouleme O, Tzarou V, Chatzizisi O, Patsiaoura K, Papageorgiou A, Leontsini M, Eugenidis N, Zamboulis C. Colchicine treatment of liver fibrosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:281-285. |

| 12. | Arrieta O, Rodriguez-Diaz JL, Rosas-Camargo V, Morales-Espinosa D, Ponce de Leon S, Kershenobich D, Leon-Rodriguez E. Colchicine delays the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis virus-related liver cirrhosis. Cancer. 2006;107:1852-1858. |

| 13. | Berrebi W, Hartmann DJ, Jouanolle H, Paterom D, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M. Could serum N-terminal peptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP) take place of liver biopsy for the follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC)? Hepatology. 1991;14:199A. |

| 14. | Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457-481. |

| 15. | Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, Mantel N, McPherson K, Peto J, Smith PG. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1-39. |

| 16. | Munro BH, Visintainer MA, Batten Page E. Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co 1986; 263-289. |

| 17. | Lin DY, Sheen IS, Chu CM, Liaw YF. A prospective randomized trial of colchicine in prevention of liver cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:961-966. |

| 18. | Angelico M, Cepparulo M, Barlattani A, Liuti A, Gentile S, Hurtova M, Ombres D, Guarascio P, Rocchi G, Angelico F. Unfavourable effects of colchicine in combination with interferon-alpha in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1459-1467. |

| 19. | Morgan TR, Weiss DG, Nemchausky B, Schiff ER, Anand B, Simon F, Kidao J, Cecil B, Mendenhall CL, Nelson D. Colchicine treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:882-890. |

| 20. | Tome S, Lucey MR. Review article: current management of alcoholic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:707-714. |

| 21. | Almasio PL, Floreani A, Chiaramonte M, Provenzano G, Battezzati P, Crosignani A, Podda M, Todros L, Rosina F, Saccoccio G. Multicentre randomized placebo-controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid with or without colchicine in symptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1645-1652. |

| 22. | Afdhal NH, Levine R, Levine R, Freillich B, O’Brien M, Brass C. Colchicine versus Peg-Interferon Alfa 2b long term therapy: Results of the 4 year COPILOT trial. 43rd annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL 2008); 2008 Apr 23-27; Milan, Italy. |

| 23. | Grace ND. Colchicine treatment of cirrhosis: questions. Hepatology. 1989;9:655-656. |

| 24. | Rambaldi A, Gluud C. Colchicine for alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. Liver. 2002;21:129-136. |

| 25. | Liu CY, Liao HF, Shih SC, Lin SC, Chang WH, Chu CH, Wang TE, Chen YJ. Colchicine sensitizes human hepatocellular carcinoma cells to damages caused by radiation. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4237-4240. |

| 26. | Dufour JF, DeLellis R, Kaplan MM. Reversibility of hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:981-985. |