Published online May 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2520

Revised: February 14, 2010

Accepted: February 21, 2010

Published online: May 28, 2010

AIM: To determine the rate and yield of repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for dyspepsia in clinical practice, whether second opinions drive its use, and whether it is performed at the expense of colorectal cancer screening.

METHODS: We performed a retrospective cohort study of all patients who underwent repeat EGD for dyspepsia from 1996 to 2006 at the University of California, San Francisco endoscopy service.

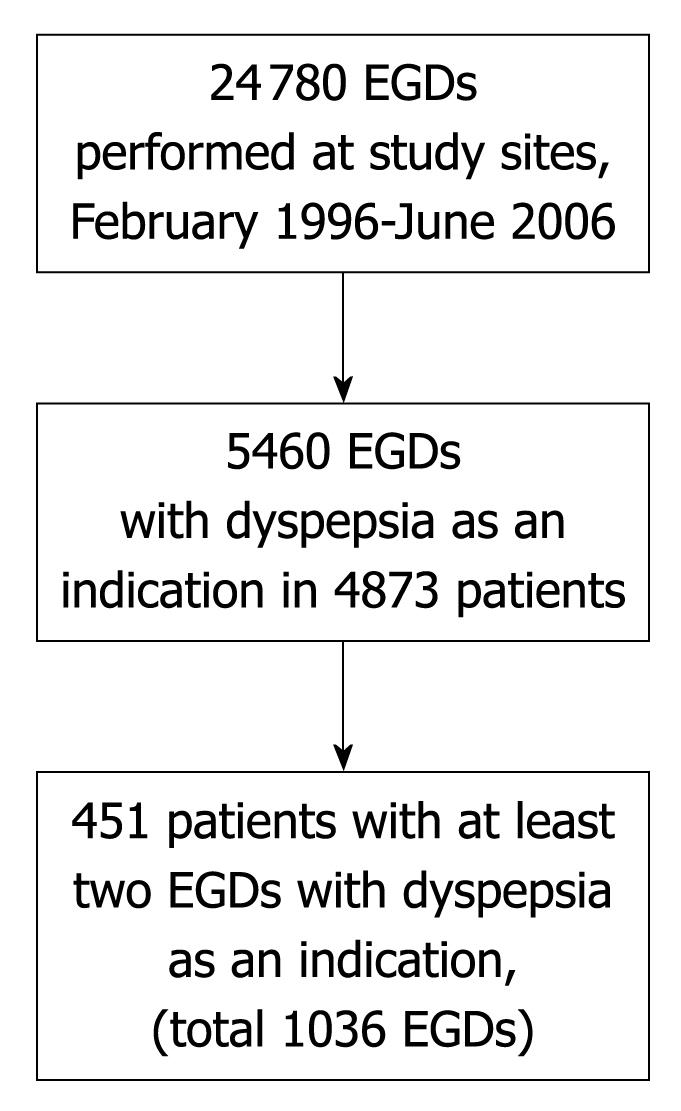

RESULTS: Of 24 780 EGDs, 5460 (22%) were performed for dyspepsia in 4873 patients. Of these, 451 patients (9.3%) underwent repeat EGD for dyspepsia at a median 1.7 (interquartile range, 0.8-3.1) years after initial EGD. Significant findings possibly related to dyspepsia were more likely at initial (29%) vs repeat EGD (18%) [odds ratio (OR), 1.45; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.20-1.75, P < 0.0001], and at repeat EGD if the initial EGD had reported such findings (26%) than if it had not (14%) (OR, 1.32; 95% CI: 1.08-1.62, P = 0.0015). The same endoscopist performed the repeat and initial EGD in 77% of cases. Of patients aged 50 years or older, 286/311 (92%) underwent lower endoscopy.

CONCLUSION: Repeat EGD for dyspepsia occurred at a low but substantial rate, with lower yield than initial EGD. Optimizing endoscopy use remains a public health priority.

- Citation: Ladabaum U, Dinh V. Rate and yield of repeat upper endoscopy in patients with dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(20): 2520-2525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i20/2520.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2520

Dyspepsia, which can be defined as chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, is a highly prevalent condition, affecting approximately 20% of the population in Western countries[1-4]. The major causes of dyspepsia are peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, malignancy, and functional dyspepsia[5]. The evaluation and management of dyspepsia constitutes a significant clinical and economic burden[6-8].

Non-invasive strategies, including testing and treatment for Helicobacter pylori, are recommended for younger persons without alarm symptoms, while prompt esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is recommended for older persons and those with alarm symptoms[9-11]. An important aim has been to decrease the use of EGD, which is costly and reveals no abnormalities in the majority of patients with dyspepsia[5]. In randomized, controlled trials in multiple countries, non-invasive strategies for dyspepsia led to EGD within 1 year in 2%-50% of patients[12-17]. In these trials, 5%-25% of patients assigned to prompt EGD underwent repeat EGD within 1 year[13-15,17] reflecting the frequently persistent nature of dyspepsia, the difficulty in managing patients with functional dyspepsia[18,19], and the imperfect reassurance value of a normal endoscopy[20-22].

The rate and yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia in clinical practice, outside of a controlled trial, is unknown. We performed a retrospective, observational study to determine the rate and yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia in the endoscopy service of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), USA. We examined whether different endoscopists performed the initial and repeat EGDs in order to shed light on whether the performance of repeat EGD could be related to patients seeking a second opinion. Given the benefits of colorectal cancer screening, we determined the rate of lower endoscopy in patients undergoing repeat EGD for dyspepsia in order to explore whether endoscopic resources might have been used more optimally.

The study was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. The study sites were Moffitt-Long Hospital, a university tertiary care medical center that also serves as a community hospital for many patients, and Mount Zion Hospital and Clinics, an integral part of the University of California, San Francisco system that serves primary, secondary and tertiary care patients. Records were available for all endoscopic reports from February 1996 to June 2006 in an endoscopic database that serves both sites (Pentax EndoPRO, Version 6.5.2, copyright 1998-2005, Pentax Precision Instrument Co., Orangeburg, New York). We have used this database and methods similar to those of this study in previous investigations[23]. The source population for the study consisted of all patients undergoing any EGD at either site during the study period.

The endoscopic database was searched systematically to identify all patients who underwent EGD for the evaluation of dyspepsia. Dyspepsia as an indication was defined as any of the following terms in the database’s “Indications” field: “dyspepsia”, “abdominal pain”, “abdominal pain despite treatment”, “abdominal pain suggesting organic disease”, and “bloating”. All patients who underwent at least 2 EGDs with an indication of dyspepsia during the study period were included. For all studies in which biopsies were performed because of suspected malignancy or Barrett’s esophagus, histological diagnoses were confirmed by review of electronic pathology records.

Data were extracted from the endoscopy and pathology reports and entered into matrix format (Excel 2000, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Demographic data included gender and date of birth. Data characterizing the procedure included procedure date, physician, and procedure sequence for a given patient (first or second EGD, or subsequent EGDs). By definition, all procedures included dyspepsia as an indication. Additional indications were recorded and categorized as abnormal imaging study, anemia or gastrointestinal bleeding, anorexia and/or weight loss, dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms, nausea and/or vomiting, follow-up of ulcer, follow-up of Barrett’s esophagus, cirrhosis-related, diarrhea and miscellaneous. Findings at endoscopy were recorded and categorized as esophagitis, hiatal hernia, esophageal stricture, gastritis, gastric erosions, gastric ulcer, gastric polyps, duodenitis, duodenal erosions, duodenal ulcer, duodenal stricture, biopsy-proven malignancy, a new diagnosis of biopsy-confirmed Barrett’s esophagus, and retained food suggesting gastroparesis. A significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia was defined as esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcer, or biopsy-proven malignancy. We also performed analyses with a less stringent definition of a significant finding that also included gastric or duodenal erosions.

An additional search was performed to identify which study patients had undergone a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy at any point during the study period. The purpose was to determine whether subjects had undergone procedures that could serve as endoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening.

Data were imported into SAS v9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for analysis. Procedures were subgrouped into those that had dyspepsia as the exclusive indication and those that had dyspepsia and additional indications. Summary descriptive statistics for demographic descriptors, indications, and findings were calculated for the set of first (initial) EGDs, second (repeat) EGDs, and so on. Relatively few subjects underwent 4 or more EGDs.

Analyses specified a priori were performed. Endoscopic findings were compared between EGDs that included only dyspepsia as an indication and those that included dyspepsia and additional indications. Procedure dates were compared between initial and repeat EGDs for each subject in order to determine the time elapsed between procedures. Endoscopic findings were compared between initial and repeat EGDs in order to determine whether the rate of significant findings differed between these. Endoscopic findings at repeat EGD were compared between subjects who did and did not have significant findings at initial EGD. Endoscopists performing the initial and repeat EGD were compared to determine whether the same or a different endoscopist performed the procedures.

Continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test, and means with SD are reported. Where appropriate, medians with interquartile ranges are reported. Proportions were compared with the χ2 test and Mantel-Haenszel odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Statistical significance was set at Pα≤ 0.05.

Figure 1 depicts the study population. During the study period, a total of 24 780 EGDs were performed at the study sites. Of these, 5460 (22%) included dyspepsia as an indication for the procedure. These 5460 EGDs were performed in 4873 unique patients. A total of 451 of these patients (9.3% of all patients who underwent EGD for dyspepsia) underwent at least 2 EGDs with dyspepsia as an indication, with a total of 1036 EGDs performed with dyspepsia as an indication in this subgroup. The number of patients who underwent 3 or more EGDs with dyspepsia as an indication was 90 having 3 EGDs, 29 having 4 EGDs, 8 having 5 EGDs, 5 having 6 EGDs, 1 having 7 EGDs and 1 having 8 EGDs. Of the 5460 EGDs with dyspepsia as an indication, 585 (10.7%) were second or subsequent EGDs for dyspepsia.

The demographic and procedure-related characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. The proportions of EGDs that included dyspepsia as an exclusive indication were nearly identical for the initial and repeat EGDs (56%-57%). Repeat EGD was performed a median of 1.7 (IQR, 0.8-3.1) years after the initial EGD.

| Initial EGD (n = 451) | Repeat EGD (n = 451) | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 53.4 ± 18.8 | 55.6 ± 19.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 285 (63) | 285 (63) |

| Male | 166 (37) | 166 (37) |

| Time from first to second EGD [yr, median (interquartile range)] | -- | 1.7 (0.8-3.1) |

| Indications | ||

| Dyspepsia exclusively | 255 (57) | 253 (56) |

| Dyspepsia and additional indication(s) | 196 (43) | 198 (44) |

The indications for the initial and repeat EGD for the patients are shown in Table 2. The distributions of indications classified as “dyspepsia” and those defined as additional indications were each similar for the initial and repeat EGDs.

| Initial EGD (n = 451) | Repeat EGD (n = 451) | |

| Dyspepsia | 451 (100) | 451 (100) |

| Dyspepsia | 196 (44) | 159 (35) |

| Abdominal pain | 168 (37) | 199 (44) |

| Abdominal pain despite treatment | 115 (26) | 103 (23) |

| Abdominal pain suggesting organic disease | 10 (2) | 17 (4) |

| Bloating | 11 (2) | 24 (5) |

| Additional Indications | 196 (43) | 198 (44) |

| Abnormal imaging study | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Anemia or gastrointestinal bleeding | 27 (6) | 15 (3) |

| Anorexia and/or weight loss | 17 (4) | 16 (4) |

| Dysphagia | 68 (15) | 42 (9) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms | 56 (12) | 77 (17) |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 26 (6) | 33 (7) |

| Follow-up of ulcer | 9 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Follow-up of Barrett’s esophagus | 5 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Cirrhosis-related | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Diarrhea | 22 (5) | 20 (4) |

| Miscellaneous1 | 12 (3) | 16 (4) |

The findings at the initial and repeat EGD for the patients are shown in Table 3. A minority of EGDs showed significant abnormalities. The proportion of EGDs showing a significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia was higher for the initial EGD (133/451, 29%) than for the repeat EGD (79/451, 18%) (OR, 1.45; 95% CI: 1.20-1.75, P < 0.0001). There was a higher rate of significant findings possibly related to dyspepsia on the repeat EGD if the initial EGD had reported such findings (35/133, 26%) than if it had not (44/318, 14%) (OR, 1.32; 95% CI: 1.08-1.62, P = 0.0015).

| Initial EGD (n = 451) | Repeat EGD (n = 451) | |

| Esophagitis | 95 (21) | 59 (13) |

| Hiatal hernia | 160 (36) | 172 (38) |

| Esophageal stricture | 13 (3) | 10 (2) |

| Gastritis | 221 (49) | 196 (43) |

| Gastric erosions | 44 (10) | 40 (9) |

| Gastric ulcer | 31 (7) | 14 (3) |

| Gastric polyps | 21 (5) | 21 (5) |

| Duodenitis | 35 (8) | 24 (5) |

| Duodenal erosions | 6 (1) | 3 (0.7) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 13 (3) | 8 (2) |

| Duodenal stricture | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| Retained food suggesting gastroparesis | 2 (0.5) | 8 (2) |

| Postoperative changes | 11 (2) | 18 (4) |

| Biopsy-proven malignancy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Biopsy-proven Barrett’s esophagus (new diagnosis) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) |

| Significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia1 | 133 (29)2 | 79 (18)2 |

The 44 patients who had significant findings only at the repeat EGD had a mean age of 52 (± 23) years at initial EGD, a median time to repeat EGD of 1.8 (IQR, 0.7-4.1) years, and 28/44 (64%) were female. In 27 (61%) of these patients, dyspepsia was the only indication for repeat EGD, while indications in addition to dyspepsia in the other 17 included bleeding, weight loss, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, dysphagia, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. At repeat EGD, the findings were esophagitis in 31 (70%), gastric ulcer in 9 (20%), duodenal ulcer in 3 (7%), and esophagitis and gastric ulcer in 1 (2%). It is not possible to determine whether the findings at repeat EGD were missed at initial EGD.

For the initial EGD, the proportion of tests showing a significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia was higher for procedures with dyspepsia and additional indication(s) than for procedures with dyspepsia as the exclusive indication (36%, or 71/196 vs 24%, or 62/255; OR, 1.30; 95% CI: 1.06-1.59, P = 0.006). In contrast, for repeat EGD, the proportions of tests showing a significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia did not differ significantly between procedures with dyspepsia and additional indication(s) and procedures with dyspepsia as the exclusive indication (18%, or 36/198 vs 17%, or 43/253; OR, 1.04; 95% CI: 0.83-1.29, P = 0.74).

With a less stringent definition of a significant finding that also included gastric or duodenal erosions, the proportion of EGDs showing a significant finding possibly related to dyspepsia remained higher for initial EGD (172/451, 38%) than for repeat EGD (111/451, 25%) (OR, 1.40; 95% CI: 1.19-1.65, P < 0.0001). With this less stringent definition, there was a trend towards a higher rate of significant findings possibly related to dyspepsia on repeat EGD if initial EGD had reported such findings (51/172, 29%) than if it had not (60/279, 22%) (OR, 1.19; 95% CI: 0.99-1.44, P = 0.051).

The repeat EGD was performed by the same physician who performed the initial EGD in 77% (346/451) of the cases.

Of the 451 study patients, 393 (87%) underwent either a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Among those aged 50 years or older, 286/311 (92%) underwent either a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy compared to 107/140 (76%) of those younger than 50 years (OR, 2.09; 95% CI: 1.59-2.75, P < 0.0001).

In our observational study, over 20% of all EGDs performed included dyspepsia as an indication. Of patients undergoing EGD with dyspepsia as an indication, approximately 9% underwent repeat EGDs for dyspepsia at a median 1.7 years after the initial EGD. This constituted a relatively small but still substantial fraction of endoscopic volume related to dyspepsia. The yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia was modest, and lower than the yield of initial EGD. For initial EGD, the yield was higher for EGDs performed for dyspepsia and additional indications compared with dyspepsia exclusively. In the vast majority of cases, the repeat EGD was performed by the same endoscopist as the initial EGD, suggesting that the seeking of a second opinion was not a major driver in the rate of repeat EGD. Over 90% of patients aged 50 years or older who underwent repeat EGD for dyspepsia also underwent either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, suggesting that repeat EGD was not undertaken at the expense of tests that can serve for colorectal cancer screening.

Because our study was not prospective and did not capture EGDs performed outside the UCSF endoscopy service, we could not compare our results directly with the rates of repeat EGD for dyspepsia observed in the randomized trials of competing management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia. Nonetheless, the fraction of patients undergoing repeat EGD for dyspepsia in our study was within the range of 5%-25% observed in those controlled trials at 1 year[13-15,17], and within the range of 9%-26% observed in follow-up at 6 to 7 years[24,25]. If some patients who underwent an initial EGD for dyspepsia in our study cohort then underwent repeat EGD for dyspepsia at another institution, or if the “initial EGD” for dyspepsia in our study was in reality a repeat EGD, then our results would underestimate the true rate of repeat EGD for dyspepsia. In our study, repeat EGD was performed a median of 1.7 (IQR, 0.8-3.1) years after the initial EGD. Longer-term follow-up of patients in randomized trials has shown that some patients undergo repeat EGD for dyspepsia years later, but most repeat EGDs were within the initial year of the studies[13,24,25].

It is well recognized that most EGDs performed for dyspepsia demonstrate no significant abnormality[5,13-17]. Thus, the relatively low yield in our study was not surprising. The yield at repeat EGD for dyspepsia was lower than at initial EGD, a finding that might have been expected, but has not been demonstrated in clinical practice previously. Because our study design selected patients with repeat EGD for dyspepsia, the diagnostic yield at initial EGD might actually have been lower than in patients who did not undergo repeat EGD. For instance, no malignancies were diagnosed, but one could postulate that patients diagnosed with malignancy at initial EGD might be less likely to undergo repeat EGD with dyspepsia as an indication.

The management of patients with functional dyspepsia is challenging[18,19]. Patients may seek second opinions in search of underlying disease that may have been missed, or new treatments. We expected to find that a majority of repeat EGDs for dyspepsia had been performed by a different endoscopist than the initial EGDs, but this was not the case. If we failed to capture a significant fraction of all repeat EGDs for dyspepsia in our study patients because they occurred at other institutions, then the proportion of repeat vs initial EGDs performed by a different endoscopist would be higher. It is unlikely that the endoscopists in our study played the role of proceduralist instead of consultant, since open-access upper endoscopy is relatively rare in our endoscopy service. One may speculate that repeat EGD in patients with established care with a gastroenterologist could be driven in part by ongoing patient concern[20-22]. We could not address this issue directly in the current study.

With the growing national emphasis on colorectal cancer screening, the capacity and proper utilization of lower endoscopic services have been debated[26-28]. Because we expected that the yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia would be low, we sought to investigate whether endoscopic services might have been applied better towards colorectal cancer screening in our study patients. We found that a very large majority of our patients also underwent lower endoscopy, at a rate much higher than national uptake rates for colorectal cancer screening[29]. This likely reflected a group of patients who had well established medical care and might in fact utilize more medical resources than the average, as reflected by a high rate of lower endoscopy even in patients younger than 50 years of age. The endoscopic capacity in our study sites is somewhat elastic, so that a repeat EGD for dyspepsia may not directly displace a screening lower endoscopy. We could not determine whether patients outside of our study cohort were denied access to lower endoscopy as a result of the repeat EGDs that were performed. If present at all, this effect would be small. However, this may be a more salient issue in other settings with more constrained resources and different incentive structures for endoscopists.

Our study has limitations. First, because it was a retrospective study without complete coverage of all of our patients’ medical contacts, some repeat EGDs at other facilities might have been missed. However, our results accurately reflected the fraction of endoscopic services devoted to initial and repeat EGD for dyspepsia within our study sites. Second, we did not know whether patients whose EGDs were performed for abdominal pain fit the definition of dyspepsia, but we chose to include them because many endoscopists in our unit do no use the term dyspepsia in the indication field, and because we believe that when EGD is performed for abdominal pain it is likely that this pain is in the upper abdomen and can be categorized as dyspepsia. Third, we did not know the management strategies offered to patients, which could have affected the rate of repeat EGD. Fourth, our results may be generalizable to other endoscopy units with similar systems, patients and endoscopists as ours, but not necessarily to those in different practice settings. Fifth, we did not attempt to determine whether lower endoscopies were performed for diagnostic or screening purposes. However, for the purposes of determining resource use in this study, the distinction was not necessary. Finally, it is possible that some patients with abdominal pain and diarrhea had inflammatory bowel disease, and this might have contributed to the use of lower endoscopy, but diarrhea was an additional indication in only 5% of EGDs.

In conclusion, the rate of repeat EGD for dyspepsia in this study was relatively low but still substantial, and it may have underestimated the true rate because of possible repeat EGDs at other facilities. The diagnostic yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia was modest, and lower than at initial EGD. Our findings do not support the hypothesis that repeat EGD for dyspepsia in our study sites was usually performed for a second opinion by a different endoscopist. Repeat EGD for dyspepsia in our study patients was not performed at the expense of age-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Optimal allocation of endoscopic resources remains a public health priority.

Dyspepsia is a highly prevalent condition. Non-invasive strategies to evaluate dyspepsia are recommended for younger persons without alarm symptoms in large part to limit the use of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). In randomized, controlled trials, 5%-25% of patients assigned to prompt EGD to evaluate dyspepsia underwent repeat EGD within 1 year.

The rate and yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia in clinical practice is not known. The optimal use of endoscopic resources is a public healthy priority.

The authors performed a retrospective cohort study of all patients who underwent repeat EGD for dyspepsia from 1996 to 2006 at the University of California, San Francisco endoscopy service. They determined the rate and yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia, whether second opinions drove its use, and whether endoscopic resource use might have been shifted to colorectal cancer screening.

Repeat EGD for dyspepsia occurred at a low but substantial rate, and the diagnostic yield was lower than at initial EGD. Because repeat EGD was not usually performed for a second opinion, it is likely that the physician who performed an initial EGD will face the decision as to whether to perform a repeat EGD. In our cohort, repeat EGD was not performed at the expense of age-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Nonetheless, optimal use of endoscopic capacity remains a public health priority.

Dyspepsia can be defined as chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper.

This is an interesting retrospective study to demonstrate the rate and yield of repeat EGD for dyspepsia.

Peer reviewers: Javier San Martín, Chief, Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, Sanatorio Cantegril, Av. Roosevelt y P 13, Punta del Este 20100, Uruguay; Dr. Yuk Him Tam, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, China; Jae J Kim, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 50, Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 135-710, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ 3rd. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259-1268. |

| 2. | Heading RC. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population: a systematic review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:3-8. |

| 3. | El-Serag HB, Talley NJ. Systemic review: the prevalence and clinical course of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:643-654. |

| 4. | Piessevaux H, De Winter B, Louis E, Muls V, De Looze D, Pelckmans P, Deltenre M, Urbain D, Tack J. Dyspeptic symptoms in the general population: a factor and cluster analysis of symptom groupings. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:378-388. |

| 5. | Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780. |

| 6. | Levin TR, Schmittdiel JA, Kunz K, Henning JM, Henke CJ, Colby CJ, Selby JV. Costs of acid-related disorders to a health maintenance organization. Am J Med. 1997;103:520-528. |

| 7. | Henke CJ, Levin TR, Henning JM, Potter LP. Work loss costs due to peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:788-792. |

| 8. | Moayyedi P, Mason J. Clinical and economic consequences of dyspepsia in the community. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 4:iv10-iv12. |

| 9. | Talley NJ, Vakil N. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2324-2337. |

| 10. | Talley NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1753-1755. |

| 11. | Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Bradette M, Chiba N, Armstrong D, Barkun A, Flook N, Thomson A, Bursey F. Evidence-based recommendations for short- and long-term management of uninvestigated dyspepsia in primary care: an update of the Canadian Dyspepsia Working Group (CanDys) clinical management tool. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:285-303. |

| 12. | Laheij RJ, Severens JL, Van de Lisdonk EH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB. Randomized controlled trial of omeprazole or endoscopy in patients with persistent dyspepsia: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1249-1256. |

| 13. | Lassen AT, Pedersen FM, Bytzer P, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Helicobacter pylori test-and-eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:455-460. |

| 14. | McColl KE, Murray LS, Gillen D, Walker A, Wirz A, Fletcher J, Mowat C, Henry E, Kelman A, Dickson A. Randomised trial of endoscopy with testing for Helicobacter pylori compared with non-invasive H pylori testing alone in the management of dyspepsia. BMJ. 2002;324:999-1002. |

| 15. | Arents NL, Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, Oudkerk Pool M, Gotz JM, van de Werf GT, Reenders K, Sluiter WJ, Kleibeuker JH. Approach to treatment of dyspepsia in primary care: a randomized trial comparing "test-and-treat" with prompt endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1606-1612. |

| 16. | Hu WH, Lam SK, Lam CL, Wong WM, Lam KF, Lai KC, Wong YH, Wong BC, Chan AO, Chan CK. Comparison between empirical prokinetics, Helicobacter test-and-treat and empirical endoscopy in primary-care patients presenting with dyspepsia: a one-year study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5010-5016. |

| 17. | Mahadeva S, Chia YC, Vinothini A, Mohazmi M, Goh KL. Cost-effectiveness of and satisfaction with a Helicobacter pylori "test and treat" strategy compared with prompt endoscopy in young Asians with dyspepsia. Gut. 2008;57:1214-1220. |

| 18. | Camilleri M. Functional dyspepsia: mechanisms of symptom generation and appropriate management of patients. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:649-664, xi-x. |

| 19. | Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479. |

| 20. | Wiklund I, Glise H, Jerndal P, Carlsson J, Talley NJ. Does endoscopy have a positive impact on quality of life in dyspepsia? Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:449-454. |

| 21. | Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Souchek J, Ambriz E. Impact of upper endoscopy on satisfaction in patients with previously uninvestigated dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:295-299. |

| 22. | van Kerkhoven LA, van Rossum LG, van Oijen MG, Tan AC, Laheij RJ, Jansen JB. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy does not reassure patients with functional dyspepsia. Endoscopy. 2006;38:879-885. |

| 23. | Pepin C, Ladabaum U. The yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a Veterans Administration medical center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:325-332. |

| 24. | Lassen AT, Hallas J, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Helicobacter pylori test and eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: 6.7 year follow up of a randomised trial. Gut. 2004;53:1758-1763. |

| 25. | Laheij RJ, van Rossum LG, Heinen N, Jansen JB. Long-term follow-up of empirical treatment or prompt endoscopy for patients with persistent dyspeptic symptoms? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:785-789. |

| 26. | Mysliwiec PA, Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Ransohoff DF. Are physicians doing too much colonoscopy? A national survey of colorectal surveillance after polypectomy. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:264-271. |

| 27. | Seeff LC, Manninen DL, Dong FB, Chattopadhyay SK, Nadel MR, Tangka FK, Molinari NA. Is there endoscopic capacity to provide colorectal cancer screening to the unscreened population in the United States? Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1661-1669. |

| 28. | Ladabaum U, Song K. Projected national impact of colorectal cancer screening on clinical and economic outcomes and health services demand. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1151-1162. |

| 29. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of colorectal cancer tests--United States, 2002, 2004, and 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:253-258. |