INTRODUCTION

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is the result of bacterial infection of the liver parenchyma, with subsequent infiltration by inflammatory cells and formation of a collection of pus. It is still a severe disease with considerable mortality (6%-14%)[1,2]. Chen et al[3] recently have reported an intensive care unit mortality rate of 28%. Treatment policies have changed in recent decades as a result of developments in interventional radiology that offer imaging-guided percutaneous puncture and drainage as procedures that are less invasive than surgical therapy. However, several studies have shown that underlying diseases and the overall condition of the patients have major prognostic significance[4,5]. Both the APACHE (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation) II and the SAPS (simplified acute physiology score) II scoring methods are appropriate for assessing mortality of PLA patients[6]. Thus, knowledge of etiology and timely treatment of underlying causes, when possible, play an important role in successful treatment. Recent publications from Central Europe and Southeast Asia hint at considerable differences in etiology. This editorial aims to elaborate these differences and their therapeutic implications. Information from recent publications on liver abscesses from PubMed was used. Klebsiella PLA is mainly described in series from Southeast Asia, whereas European and American studies usually comprise a mixture of different etiologies. Special interest was placed on publications devoted to characteristics and specific features of Klebsiella abscesses as compared to those of other origin.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS ON CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Antibiotic treatment is the basis of clinical PLA management. Gram stain, abscess culture (with sensitivity testing) and blood culture provide valuable information to guide successful therapy. Chemaly et al[7] have found that the sensitivity and specificity of Gram stains of liver abscess material were 90% and 100% for Gram-positive cocci (GPC) and 52% and 94% for Gram-negative bacilli (GNB). The sensitivities of the blood cultures for any GPC and GNB present in the liver abscess were 30% and 39%, respectively. Of the positive blood cultures, 35% contained organisms not recovered from abscess cultures. On the other hand, PLA pathogens are usually under-represented in blood cultures. In a recent study from Pakistan with a total of 966 patients, 540 responded to medical therapy, whereas adjunctive percutaneous aspiration was performed in 426. Predictive factors for aspiration of liver abscess were: age ≥ 55 years, size of abscess ≥ 5 cm, involvement of both lobes of the liver, and duration of symptoms ≥ 7 d[8]. Microbiology also hints at pathogenesis: local spread typically leads to mixed flora[9], and hematogenous seeding to a single microorganism (typically Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus spp.).

Apart from choosing the right antibiotic, another crucial concern is whether a sufficient concentration of the antibiotic reaches the target site. In this context, Matoba et al[10] have published an article on intermittent hepatic artery antibiotic infusion therapy, especially for patients in whom percutaneous drainage could not be performed and intravenous administration of antibiotics was ineffective. The value of this treatment (for a highly selected patient group) still has to be shown with a larger number of patients.

As for abscess drainage, the percutaneous technique has often come to replace surgical procedures. Surgery nonetheless still plays an important role when percutaneous drainage fails[11] or when underlying pathology such as biliary disease and malignancy has to be addressed[12]. In selected cases, drainage may also be done laparoscopically[13] or via a trocar in local anesthesia[14]. Hsieh et al[15] have found that aggressive hepatic resection for patients with liver abscesses and APACHE II scores of ≥ 15 produce better clinical outcomes than other therapeutic options.

PLA IN CENTRAL EUROPE

Our patients[5] show the etiological spectrum typical for our region, with biliary disorders first, followed by cryptogenic abscess, PLA due to systemic infection, and posttraumatic origin. Some other, rarer causes were also identified (portal route of infection, hydatid origin, postoperative/postprocedural, foreign body). The microorganisms found most frequently were Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Escherichia coli (E. coli). Klebsiella spp. were only found in 5% of cases. In about 25% of the patients, the abscesses were sterile and this was at least partly due to antibiotic pretreatment. Anaerobic agents are encountered with increasing frequency but this might be attributable to improved transport and culture techniques. A recent study from Spain[16] has shown similar results, with Streptococcus and E. coli found most frequently, but a higher number of Klebsiella spp. (14%). The most common complication was pleural effusion.

Prolonged disease course may result from unexpected or particularly aggressive agents, underlying pathology or constant inflammatory stimuli provoked by a foreign body. As a rare cause of pyogenic abscesses, Salmonella infection (hematogenous or ascending via the biliary tree) has been described[17-23].

Underlying pathology is frequently found in our region and is often the crucial prognostic factor. This includes gallbladder empyema, biliary fistula[24] (Figures 1 and 2), pylephlebitis secondary to acute appendicitis[25,26], and malignancy (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, liver metastases, gallbladder carcinoma, carcinoma of the papilla, and pancreatic cancer). Operative treatment of the underlying disease is indicated whenever feasible. For the healing of biliary fistula, good bile flow is crucial and may be provided by papillotomy and biliary stenting. In patients with cryptogenic PLA, silent abdominal pathology should always be considered and further studies such as colonoscopy are recommended[27].

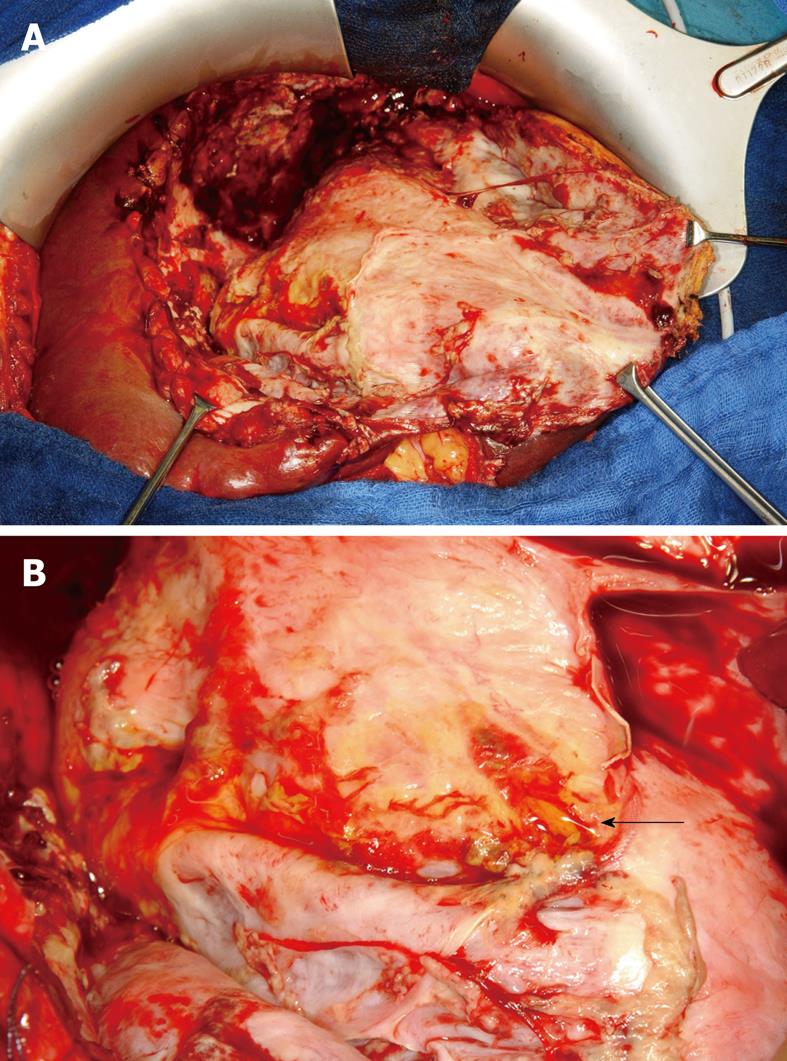

Figure 1 Posttraumatic liver abscess.

A: Intraoperative image after evacuation of putrid fluid; B: Detail from the floor of the abscess cavity showing a biliary fistula (arrow).

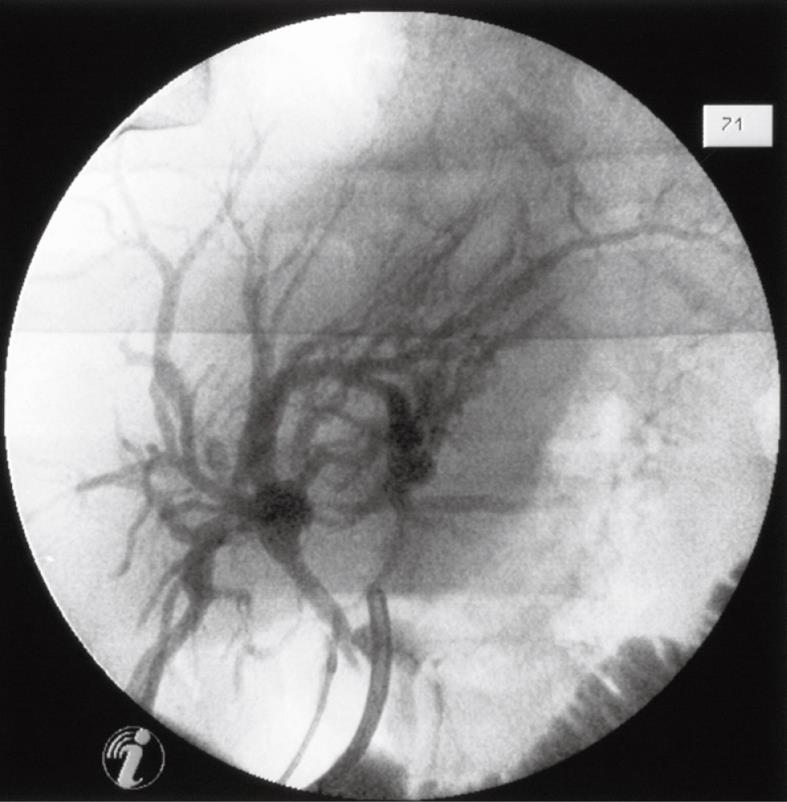

Figure 2 Intraoperative cholangiogram (injection of contrast medium into the fistula ostium).

In special cases, a foreign body penetrating from the digestive tract may provide a constant stimulus for inflammation. Several kinds of foreign bodies such as toothpick[28,29], pin[30], needle, bone[31,32], pen, dental plate, clothespin, wire crucifix, and rosemary twig[33] have been described[9]. Removal of the foreign body is crucial for successful treatment.

PLA IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) liver abscess[34-42] recently has been reported as the leading cause of PLA in Korea and Taiwan, and is described as a globally emerging infectious disease. K. pneumoniae is found as a harmless commensal but is also a frequent nosocomial pathogen (causing urinary, respiratory and blood infections) and the agent of specific human infections including Friedländer’s pneumonia, rhinoscleroma and PLA[43].

Literature on this entity predominantly comes from Southeast Asia but it has also been reported as an emerging problem in North America[44]. In a recent report from New York, 60% of the patients with Klebsiella PLA were of Asian origin, although many of them had not resided in their country of origin for quite some time[45]. Although K. pneumoniae is prevalent in patients with diabetes, it can also attack healthy people or alcoholics[46]. Foo et al[47] have found that diabetes mellitus is not a predictor of fatality. The MagA virulence gene has been described in invasive strains. According to Yeh et al[48], and in accordance with the bacterial polysaccharide gene nomenclature scheme, MagA should be renamed Wzy (KpK1), the capsular polymerase specific to K. pneumoniae serotype K1. Gas formation by mixed acid fermentation of glucose is a typical feature.

K. pneumoniae PLA constitutes a clinical entity distinct from polymicrobial liver abscess, has a high propensity to metastasize, and rarely is associated with intra-abdominal abnormalities. PLA-producing strains are commonly resistant to ampicillin. Complications include metastatic meningitis, endophthalmitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic pulmonary emboli, and necrotizing fasciitis. Braiteh et al[49] have described three distinct K. pneumoniae liver abscess syndromes: the polymicrobial liver abscess, the monomicrobial cryptogenic noninvasive liver abscess, and the monomicrobial cryptogenic invasive K. pneumoniae-associated liver abscess (CIKPLA) syndromes, with distinct clinical, epidemiological and outcome features. CIKPLA syndrome typically affects diabetic patients, mainly in Southeast Asia, and is complicated by septic spread to other organs.

Chen et al[50] have found that, in contrast to patients with K. pneumoniae, patients with E. coli liver abscess were more likely to be older and female, have a biliary abnormality or malignancy, pleural effusion, polymicrobial infection with anaerobic or multi-drug-resistant organisms, a higher APACHE II score, and to have been treated initially with ineffective antibiotics. K. pneumoniae patients were more likely to have diabetes mellitus and the cause of infection was often cryptogenic. A higher APACHE II score at admission and higher frequency of coexisting malignancy may have contributed to the higher mortality in E. coli PLA, but the difference was not statistically significant. Tsai et al[51] also have reported lower death rates for Klebsiella PLA. As for older patients, Chen et al[52] have found that they have a fair outcome but require longer hospitalization. After successful treatment, the recurrence rate of Klebsiella liver abscesses is reported to be low[53,54]. Kim et al[55] have described the differences in CT findings of Klebsiella and non-Klebsiella liver abscesses. The former has a series of characteristic intra-abscess features: septal breakage, turquoise-like structure, hairball-like content, air-fluid level, and no enhanced rim.

Another entity well known in endemic areas of echinococcosis, but only occasionally found in Central Europe, is liver abscess of hydatid origin[56]. It is usually associated with few symptoms, because the pericystic structure acts as a nonspecific defense mechanism. Anthelminthic drugs are of limited value.

POSTPROCEDURAL AND POSTTRAUMATIC PLA

These special forms of PLA are seen in Central Europe and South East Asia. Postprocedural PLA may occur after hepatic resection; formation of pus in the operation cavity is usually amenable to percutaneous drainage. Post-transplantation liver abscesses, however, pose more complex problems. The most common predisposing factor is hepatic artery thrombosis, which may lead to fulminant hepatic necrosis, delayed bile leakage or relapsing bacteremia. In contrast to the normal liver, the graft lacks natural attachments and collaterals. Mortality of this type of PLA is still high (42%)[57] and mean duration of drainage is long. PLAs may also occur after transarterial chemoembolization[58,59] for malignant hepatic tumors, particularly after biliary reconstructive surgery (aggressive antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for these patients). They are also seen as rare complications after radiofrequency ablation[60-62] or cryosurgery[63].

About 5% of PLAs are of posttraumatic origin; they occur in 0.7%-1.5% of patients undergoing nonoperative treatment of liver trauma caused by bacterial seeding of hematoma or necrosis[64,65]. Risk factors include enteric injuries, persistent hemorrhage with excessive need of blood transfusions, and extensive parenchymal damage. The necessity for antibiotic prophylaxis in liver trauma patients remains an unresolved question; it might be justified with liver injury of at least grade 3 and is usually given with associated open wounds.

CONCLUSION

Apart from some special types of PLA that are comparable in Southeast Asia and Central Europe (such as posttraumatic or postprocedural PLA), there are clear differences in the microbiological spectrum, which also implies different risk factors and courses. K. pneumoniae PLA is predominantly seen in Southeast Asia, whereas, in Central Europe, PLA is typically caused by E. coli, Streptococcus or Staphylococcus and these patients are more likely to be older and to have a biliary abnormality or malignancy, pleural effusions, and a higher APACHE II score. K. pneumoniae patients are more likely to have diabetes mellitus and the cause of infection is often cryptogenic. The typical complication for Klebsiella infection is metastatic spread to various organs. On the other hand, high APACHE II scores at admission and a high frequency of coexisting malignancy may often contribute to a critical course in Central European PLA patients. Control of septic spread is crucial in K. pneumoniae patients, whereas treatment of the underlying diseases is a decisive issue in many Central European PLA patients.

Peer reviewer: Douglas G Farmer, MD, Associate Professor of Surgery, Director, Intestinal Transplant Program, Surgical Director, Pediatric Liver Transplant Program, Dumont-UCLA Transplant Center, Room 77-120 CHS, Box 957054, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7054, United States

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM