Published online May 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2421

Revised: March 19, 2010

Accepted: March 26, 2010

Published online: May 21, 2010

AIM: To investigate the role of enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) and STAT6 immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of clinical stages and prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC).

METHODS: The expression patterns were examined by immunohistochemistry in both tumor and adjacent non-neoplastic tissues of 119 CRC patients who underwent operation during the time period from 2002 to 2004.

RESULTS: The positive rates of EZH2 and STAT6 in CRC cases were 69.7% (83 of 119) and 60.5% (72 of 119), respectively, and there was significant difference when compared with tumor adjacent non-neoplastic tissues (P < 0.05). In all CRC cases, patients with EZH2-positive, or STAT6-positive expression had lower survival rates than those with EZH2-negative or STAT6-negative expression (P = 0.002 and P = 0.005, respectively). Co-expression of EZH2 and STAT6 showed significantly higher levels in CRC cases of high clinical TNM stages (P = 0.001), and the expression of STAT6 was also correlated with lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis (P = 0.001 and P = 0.016, respectively). Multivariate analysis revealed that EZH2 expression was an independent prognostic indicator of CRC (P = 0.039).

CONCLUSION: EZH2 and STAT6 expressions have significant values in distinguishing clinical stages of CRC and predicting the prognosis of the patients.

- Citation: Wang CG, Ye YJ, Yuan J, Liu FF, Zhang H, Wang S. EZH2 and STAT6 expression profiles are correlated with colorectal cancer stage and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(19): 2421-2427

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i19/2421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2421

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer, and the second leading cause of death from cancers in the United States[1]. Many Asian countries, including China, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, have experienced an increase of 2-4 times in the incidence of CRC during the past few decades[2]. To reduce the mortality and improve treatment, a number of studies have been performed to search for tumor biomarkers, especially for those highly correlated with both staging and prognosis that can help not only predict patients’ survival, but also lead to optimal therapeutic project.

EZH2 is a member of the polycomb group of genes (PcG), which is important for transcriptional regulation through nucleosome modification, chromatin remodeling, and interaction with other transcription factors[3]. EZH2, also called histone lysine methyltransferase (HKMT), has the function of methylating lysine 9 and 27 of histone H3, which consequently leads to the repression of target gene expression. Furthermore, dysregulation of this gene silencing mechanism may lead to cancer[4,5]. Recently, EZH2 has been investigated as a potential molecular biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer by Varambally et al[6], using cDNA microarray analysis. Overexpression of EZH2 has been observed in the most aggressive forms of prostate cancer, exhibiting a correlation with poor clinical outcome, thus acting as a novel marker of aggressiveness and unfavorable prognosis in this type of cancer. A causal effect between EZH2 up-regulation and poor prognosis was also observed in human gastric cancers[7]. However, there have been few reports of EZH2 expression in CRC, and its relationship with clinicopathological characteristics or prognostic value is yet unclear.

Like other members of the signal STAT (transcriptional activation by signal transducer and activator of transcription) family of proteins, STAT6 has a dual role as a signaling molecule and transcription factor. STAT6 is activated in response to interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 stimulation, and plays a key role in Th2 polarization of the immune system[8]. Recently, the STAT6 signaling pathway was found to be highly activated in some tumors, such as prostate cancer, mammary carcinoma and lymphoma[9-11]. In addition, a close correlation between IL-4/STAT6 activities and apoptosis and metastasis of colon cancer was reported by Li et al[12] in a study using STAT6-high and STAT 6-null colon cancer cell lines to analyze anti-apoptotic and pro-metastatic genes expression. Nevertheless, there have been no studies investigating the clinicopathological features and prognosis of CRC in relation to STAT6 expression. In this study, we analyzed the expression of EZH2 and STAT6 in biopsied CRC tissues to determine their relationship with clinicopathological features and clinical outcome of CRC patients.

A group of 119 consecutive patients with CRC were studied. All patients were diagnosed and treated in the Beijing People’s Hospital between December 2002 and June 2004. There were 74 men and 45 women with a mean age of 62.2 ± 12.8 years (range 25-89 years). No patient had received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. All of the patients were followed up by direct evaluation or phone interview until death or December 2008. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital, Peking University.

Core tissue biopsies (2 mm in diameter) were taken from Formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples and adjacent non-neoplastic tissues. These blocks were arranged in a new recipient paraffin block (tissue array block) using a commercially available micro-array instrument (Beecher Instruments, Micro-Array Technologies, Silver Spring, MD). Two cores were sampled from each case. From the 119 tumor samples and adjacent non-neoplastic tissues, 11 tissue array blocks were prepared, each containing 10-12 tumor and adjacent non-neoplastic sample cores. To qualify for this study, a case needed to have a tumor occupying more than 10% of the core tissue area. Clinical and pathological information for this group of patients was obtained by review of histopathological reports and medical records.

Eleven paraffin-embedded blocks of tissue arrays were cut into 4-mm sections. The sections were put in the oven at 59°C for 1h, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was done by microwaving the tissue in 10 mmol/L citric acid buffer for 10 min, then cooling to room temperature for 1 h. The sections were incubated with an anti-EZH2 monoclonal antibody (1:500, Invitrogen), and an anti-STAT6 monoclonal antibody (1:100, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were detected using the Powervision two-step histostaining reagent (Zhongshan, Beijing), with PV-6001 as the secondary antibody and detection was performed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogenic reaction. Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin, 1% hydrochloric acid of alcohol, dehydrated with graded ethanols, and mounted. Positive and negative immunohistochemical controls were included. Two experienced pathologists independently examined EZH2 and STAT6 staining while blinded to the clinicopathological data and clinical outcomes of the patients. Cases with > 30% positive tumor cells in a section were recorded as having positive expression. As negative controls, samples were stained with only secondary antibody. A total of 119 cases were used for data analysis.

All data were analyzed using SPSS 11.0 software. The association of EZH2 and STAT6 expression with various clinicopathological features was analyzed using χ2 test. Cumulative survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between survival curves were analyzed by log-rank test. The influence of each variable on survival was analyzed by multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

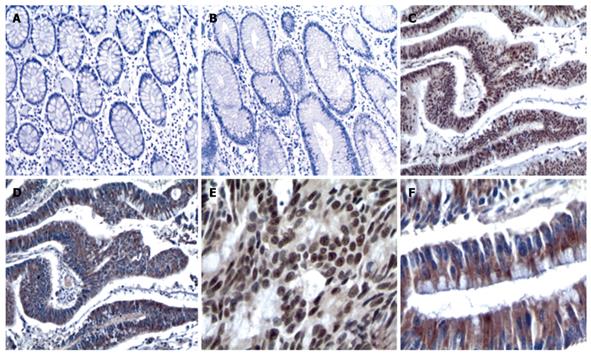

Positive and negative staining of EZH2 and STAT6 are illustrated in Table 1. The positive rates of EZH2 and STAT6 were 69.7% (83 of 119) and 60.5% (72 of 119), respectively in CRC cases, and there was an obvious difference when compared with tumor adjacent non-neoplastic tissues (P < 0.05). We observed that EZH2 expression was mainly present in the nuclei in most of the cases, and EZH2 immunoreactivity was found not only in the nuclei but also in the cytoplasm in a few CRC samples (8 of 110). STAT6 expression was mostly detected in the cytoplasm, and at cell membranes in some cases (Figure 1).

| Cases | EZH2 expression | P | STAT6 expression | P | |||

| EZH2+ | EZH2- | STAT6+ | STAT6- | ||||

| Tissue | |||||||

| Non-neoplastic samples | 22 | 97 | 0.000 | 50 | 69 | 0.004 | |

| Tumor samples | 83 | 36 | 72 | 47 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 47 | 30 | 17 | 0.334 | 24 | 23 | 0.089 |

| Male | 72 | 52 | 20 | 48 | 24 | ||

| Location | |||||||

| Colon | 90 | 62 | 28 | 0.719 | 57 | 33 | 0.268 |

| Rectum | 29 | 21 | 8 | 15 | 14 | ||

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Poor | 21 | 16 | 5 | 0.479 | 16 | 5 | 0.101 |

| Moderate or well | 98 | 67 | 31 | 56 | 42 | ||

| TNM classification | |||||||

| I | 11 | 4 | 7 | 0.049 | 3 | 8 | 0.004 |

| II | 42 | 29 | 13 | 20 | 22 | ||

| III | 44 | 35 | 9 | 32 | 12 | ||

| IV | 22 | 15 | 7 | 17 | 5 | ||

| Depth of wall invasion | |||||||

| T1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.014 | 1 | 0 | 0.188 |

| T2 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 11 | ||

| T3 | 93 | 71 | 22 | 58 | 35 | ||

| T4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||||

| No | 55 | 34 | 21 | 0.081 | 25 | 30 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 64 | 49 | 15 | 47 | 16 | ||

| Distant metastasis | |||||||

| M0 | 97 | 66 | 31 | 0.668 | 54 | 43 | 0.024 |

| M1 | 22 | 16 | 6 | 18 | 4 | ||

| Recurrence | |||||||

| No | 86 | 61 | 25 | 0.088 | 53 | 33 | 0.775 |

| Yes | 11 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | ||

The expression of EZH2 in CRC samples was significantly correlated with more malignant phenotypes, including TNM classification (P = 0.049), and tumor invasion depth (P = 0.014). The expression of EZH2 had nothing to do with gender, tumor location, differentiation, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis. There was no significant correlation between cytoplasmic EZH2 immunoreactivity and clinicopathological features in the CRC carcinoma tissue samples (data not shown).

We found a positive correlation between STAT6 expression and TNM classification (P = 0.004), and expression of STAT6 was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis (P = 0.001) and distant metastasis (P = 0.024). As shown in Table 1, expression of STAT6 was not correlated with other clinicopathological features.

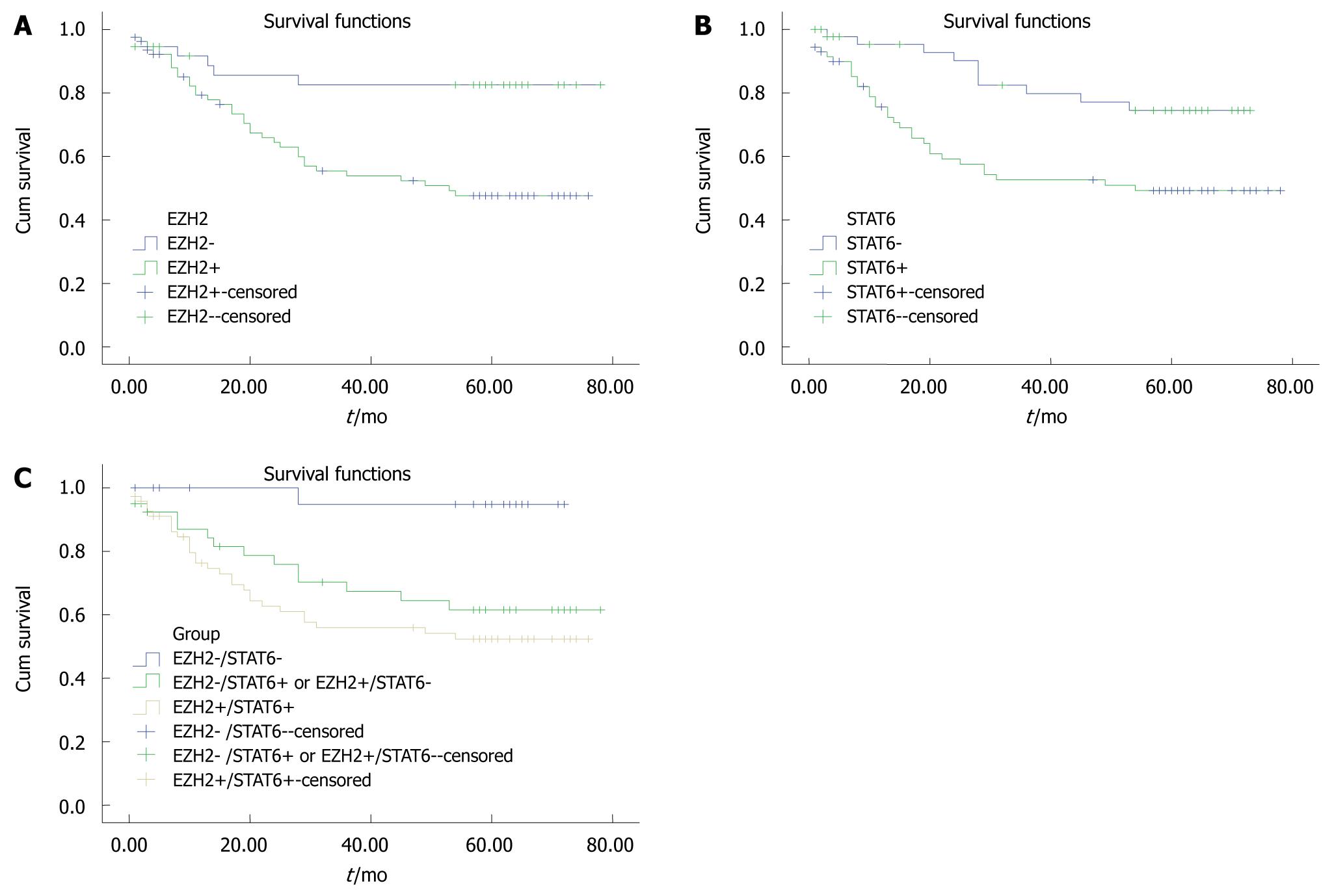

Tissue biopsies with EZH2-positive cells had a significantly lower post-operative survival rate than tissue biopsies with EZH2-negative cells (P = 0.02, Figure 2A). The STAT6-positive group also had significantly lower survival rates than the STAT6-negative group (P = 0.005, Figure 2B).

On the basis of the expression profiles of EZH2 and STAT6, the 119 patients were categorized into three groups: Group A: EZH2-/STAT6- (n = 30); Group B: EZH2+/STAT6- or EZH2-/STAT6+ (n = 40); and Group C: EZH2+/STAT6+ (n = 59). There were significant differences in survival rates between group A and one of the other groups (P = 0.006, Figure 2C). The survival rate of group A was significantly higher than that of group B (P = 0.008), the survival rate of group B was not significantly higher than that of group C (P = 0.333), and the survival rate of group A was significantly higher than that of group C (P = 0.001, Figure 2C).

Using Cox regression analysis for the 119 patient samples, positive EZH2 expression (P = 0.039), distant metastasis (P = 0.000), and lymph node metastasis (P = 0.018) seemed to be independent prognostic indicators (Table 2).

| B | P | RR | 95% CI for RR | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Metastasis | 3.075 | 0.000 | 21.648 | 8.212 | 57.070 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1.149 | 0.018 | 3.157 | 1.218 | 8.178 |

| Grading | -0.675 | 0.051 | 0.509 | 0.258 | 1.003 |

| Recurrence | 0.510 | 0.173 | 1.665 | 0.799 | 3.469 |

| EZH2 | 1.167 | 0.039 | 3.214 | 1.061 | 9.732 |

A significant association was found between EZH2 and STAT6 expression by Spearman’s correlation analysis (rs = 0.329, P = 0.00; Table 3), when EZH2 and STAT6 expressions were evaluated. Table 4 shows the relationship between the expression profile of EZH2 and STAT6 and TNM classification assignment for 119 CRC samples. Co-expression of EZH2 and STAT6 was significantly correlated with high clinical TNM classification (P = 0.003). Furthermore, the expression levels of co-expression of EZH2 and STAT6 tended to rise as the TMN staging increased (18%, 40%, 59% and 72% in stages I-IV, respectively).

| EZH2 | STAT6 | Total | |

| + | - | ||

| + | 59 | 24 | 83 |

| - | 13 | 23 | 36 |

| Total | 72 | 47 | 119 |

| TNM classification | EZH2 and STAT6 expressions | EZH2+ and STAT6+ expression in different stages(%) | |||

| EZH2+ and STAT6+ | EZH2-or STAT6- | EZH2- and STAT6- | Total | ||

| I | 2 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 18 |

| II | 15 | 19 | 8 | 42 | 40 |

| III | 26 | 10 | 8 | 44 | 59 |

| IV | 16 | 5 | 1 | 22 | 72 |

| Total | 59 | 37 | 23 | 119 | 49 |

In the present study, we have found that EZH2 and STAT6 are sensitive and potential biomarkers that can be used for the prediction of clinical TNM classification and prognosis of CRC. An association between EZH2 overexpression and the biological malignancy of tumors has been reported in many cancers, including breast cancer, lymphoma, bladder carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Those studies suggested that EZH2 may play a role in carcinoma progression and indicate a worse clinical outcome[13-16]. Fluge et al[17] investigated the expression of EZH2 in colorectal cancer by IHC. The authors concluded that a strong EZH2 expression indicated an improved relapse-free survival. Notably, this finding was only seen in colonic cancer, but not in rectal cancer. Interestingly, this result is conflicted with Mimori’ study[18], who believes that EZH2 may be an oncogene and a prognostic marker in either colonic or rectal cancer. In our study, no relationship was found between the expression of EZH2 and colorectal tumor location. Furthermore, those CRC cases with higher levels of EZH2 expression were of more malignant phenotypes and have poorer prognosis.

The underlying mechanism is related, most probably, to tumor suppressor gene silencing by EZH2 mediated histone methylation and DNA methylation[19]. We found a positive correlation between EZH2 expression and TNM staging. Multivariate analysis revealed that EZH2 represents an independent prognostic indicator. These findings suggest the potential clinical utility of incorporating EZH2 into clinical consideration to help determine the clinical TNM staging and predict the outcome.

Our data showed that STAT6 expression was positively related to clinical TNM staging, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, suggesting that STAT6 may promote the progression of cancer. STAT6 is a member of STAT family of latent transcription factors known to be activated constitutively in cancers[20]. STAT6 is activated in response to interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 stimulation, STAT6-/-mice were deficient in responsiveness to IL-4 and IL-13, hence preferentially producing CD4_Th1 cells rather than CD4_Th2[21]. This observation may indicate that STAT6-deficient mice might have heightened immuno-surveillance against primary and metastatic tumors, because the development of Th1 cells optimized CD8-mediated tumor immunity[22]. Our data support these mechanism studies about STAT6, and suggest that STAT6 plays a key role in progression and metastasis of CRC.

In this study, STAT6 expression was also found to be associated with a poorer prognosis and TNM classification, which was consistent with EZH2 expression. Consequently, STAT6 enhanced the predictive efficiency of EZH2 expression, and patients with positive expression of EZH2 and STAT6 had the worse outcome and higher TNM staging than patients with negative expression of EZH2 or STAT6. These results suggest that combined analysis of EZH2 and STAT6 may be a powerful biological marker to predict clinical TNM staging and prognosis. According to the NCCN guidelines, patients with different clinical stages should receive correspondingly optimal treatment protocols. Therefore, it is critical to find effective biomarkers which can predict clinical staging in order to enable clinicians to make a more precise prejudgment. Our data suggest that combined EZH2 and STAT6 analysis may have a potential ability for this purpose.

In conclusion, the prognosis of CRC patients with EZH2-positive or STAT6-positive expression is significantly worse than those CRC patients with EZH2-negative or STAT6-negtive expressions. In addition, combined analysis of EZH2 and STAT6 expressions could enable clinicians to prejudge a more accurate clinical TNM staging before operation.

Enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) is a member of the polycomb group of genes that is involved in epigenetic silencing and cell cycle regulation. Recently, EZH2, as well as STAT6 signaling pathway, were found to be highly activated in some tumors. However, the clinical significance of these proteins has not yet been determined in colorectal cancer (CRC).

Recently, EZH2 has been under investigation as a potential molecular biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis in prostate cancer. Overexpression of EZH2 has been observed in the most aggressive forms of prostate cancer, exhibiting a correlation with poor clinical outcome, thus acting as a novel marker of aggressiveness and unfavorable prognosis in this type of cancer. A causal effect between EZH2 up-regulation and poor prognosis was also observed in human gastric cancer. STAT6 has a dual role as a signaling molecule and transcription factor. STAT6 signaling pathway was found to be highly activated in some tumors, such as prostate cancer, mammary carcinoma and lymphoma. In addition, a close correlation between IL-4/STAT6 activities and apoptosis and metastasis of colon cancer was reported.

The authors found that patients with EZH2-positive expression had lower survival rates than those with EZH2-negative expression in both colonic and rectal cancers. Furthermore, the data suggest that combined analysis of EZH2 and STAT6 expression can be of significant value in distinguishing clinical stages of CRC and predicting prognosis.

The combined analysis of EZH2 and STAT6 may be a powerful biological marker, which could enable clinicians to prejudge a more accurate clinical TNM staging and prognosis of CRC patients before operation.

EZH2 is a member of the polycomb group of genes (PcG), which is important for transcriptional regulation through nucleosome modification, chromatin remodeling, and interaction with other transcription factors. EZH2, also called histone lysine methyltransferase (HKMT), has the function of methylating lysine 9 and 27 of histone H3, which consequently leads to the repression of target gene expression.

Generally, the paper is well written and designed.

Peer reviewer: Stefan Riss, MD, Department of General Surgery, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Levin TR. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130-160. |

| 2. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871-876. |

| 3. | Bachmann IM, Halvorsen OJ, Collett K, Stefansson IM, Straume O, Haukaas SA, Salvesen HB, Otte AP, Akslen LA. EZH2 expression is associated with high proliferation rate and aggressive tumor subgroups in cutaneous melanoma and cancers of the endometrium, prostate, and breast. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:268-273. |

| 4. | Laible G, Wolf A, Dorn R, Reuter G, Nislow C, Lebersorger A, Popkin D, Pillus L, Jenuwein T. Mammalian homologues of the Polycomb-group gene Enhancer of zeste mediate gene silencing in Drosophila heterochromatin and at S. cerevisiae telomeres. EMBO J. 1997;16:3219-3232. |

| 5. | Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Marino S, DePinho RA, van Lohuizen M. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature. 1999;397:164-168. |

| 6. | Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624-629. |

| 7. | Matsukawa Y, Semba S, Kato H, Ito A, Yanagihara K, Yokozaki H. Expression of the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 is correlated with poor prognosis in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:484-491. |

| 8. | Hebenstreit D, Wirnsberger G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A. Signaling mechanisms, interaction partners, and target genes of STAT6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:173-188. |

| 9. | Ni Z, Lou W, Lee SO, Dhir R, DeMiguel F, Grandis JR, Gao AC. Selective activation of members of the signal transducers and activators of transcription family in prostate carcinoma. J Urol. 2002;167:1859-1862. |

| 10. | Gooch JL, Christy B, Yee D. STAT6 mediates interleukin-4 growth inhibition in human breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2002;4:324-331. |

| 11. | Skinnider BF, Elia AJ, Gascoyne RD, Patterson B, Trumper L, Kapp U, Mak TW. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 is frequently activated in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:618-626. |

| 12. | Li BH, Yang XZ, Li PD, Yuan Q, Liu XH, Yuan J, Zhang WJ. IL-4/Stat6 activities correlate with apoptosis and metastasis in colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:554-560. |

| 13. | Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Hayes DF. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11606-11611. |

| 14. | Raaphorst FM, van Kemenade FJ, Blokzijl T, Fieret E, Hamer KM, Satijn DP, Otte AP, Meijer CJ. Coexpression of BMI-1 and EZH2 polycomb group genes in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:709-715. |

| 15. | Sudo T, Utsunomiya T, Mimori K, Nagahara H, Ogawa K, Inoue H, Wakiyama S, Fujita H, Shirouzu K, Mori M. Clinicopathological significance of EZH2 mRNA expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1754-1758. |

| 16. | Qin ZK, Yang JA, Ye YL, Zhang X, Xu LH, Zhou FJ, Han H, Liu ZW, Song LB, Zeng MS. Expression of Bmi-1 is a prognostic marker in bladder cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:61. |

| 17. | Fluge Ø, Gravdal K, Carlsen E, Vonen B, Kjellevold K, Refsum S, Lilleng R, Eide TJ, Halvorsen TB, Tveit KM. Expression of EZH2 and Ki-67 in colorectal cancer and associations with treatment response and prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1282-1289. |

| 18. | Mimori K, Ogawa K, Okamoto M, Sudo T, Inoue H, Mori M. Clinical significance of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 expression in colorectal cancer cases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:376-380. |

| 19. | Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21-29. |

| 20. | Das S, Roth CP, Wasson LM, Vishwanatha JK. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-6 (STAT6) is a constitutively expressed survival factor in human prostate cancer. Prostate. 2007;67:1550-1564. |

| 21. | Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P, Clements V, Dissanayake SI, Miller S, Davis C, Danna E. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (Stat6) and CD1: inhibitors of immunosurveillance against primary tumors and metastatic disease. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:86-91. |