Published online Apr 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1655

Revised: January 25, 2010

Accepted: February 1, 2010

Published online: April 7, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the diagnostic value of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB).

METHODS: The data about 75 OGIB patients who underwent DBE in January 2007-June 2009 in our hospital were retrospectively analyzed.

RESULTS: DBE was successfully performed in all 75 patients without complication. Of the 75 patients, 44 (58.7%) had positive DBE findings, 22 had negative DBE findings but had potential bleeding at surgery and capsule endoscopy, etc. These 66 patients were finally diagnosed as OGIB which was most commonly caused by small bowel tumor (28.0%), angiodysplasia (18.7%) and Crohn’s disease (10.7%). Lesions occurred more frequently in proximal small bowel than in distal small bowel (49.3% vs 33.3%, P = 0.047).

CONCLUSION: DBE is a safe, effective and accurate procedure for the diagnosis of OGIB.

- Citation: Chen LH, Chen WG, Cao HJ, Zhang H, Shan GD, Li L, Zhang BL, Xu CF, Ding KL, Fang Y, Cheng Y, Wu CJ, Xu GQ. Double-balloon enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: A single center experience in China. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(13): 1655-1659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i13/1655.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1655

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as recurrent or persistent gastrointestinal bleeding when gastric and colonic endoscopy is negative[1]. OGIB accounts for approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal bleeding events[2]. Most OGIB events are attributable to small bowel diseases.

The detection and management of small bowel bleeding are a challenge in the past due to the length and anatomical position of small bowel. The diagnostic rate of conventional diagnostic strategies including small intestine radiography, abdominal computed tomography (CT), angiography, and red blood cell scan for small intestine disease is low[3]. Introduction of capsule endoscopy (CE) has significantly revolutionized the study of small bowel as it is a reliable method to evaluate the entire small bowel[4]. However, application of CE in diagnosis of OGIB is limited by the handing controllability, biopsy, endoscopic treatment, retention of capsule in stenosis intestine[5].

Etiological diagnosis of OGIB has been markedly improved with the development of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) since 2001[6]. DBE can be performed either through the mouth or through anus, and is thus able to explore a large part of the small bowel. DBE has the advantages including image clarity, handing controllability, biopsy, and endoscopic treatment over CE[7]. It has been demonstrated that DBE is a safe and useful procedure for the diagnosis of small intestinal disease, especially for OGIB[8]. In China, very few data are available on the diagnostic value of DBE for OGIB.

In this study, the data about 75 OGIB patients admitted to our hospital from January 2007 to June 2009 were retrospectively analyzed and the diagnostic value of DBE for OGIB was evaluated.

DBE was performed in 75 OGIB patients (37 males, 38 females, at a mean age 51.5 ± 16.6 years, range 16-86 years) admitted to our hospital in January 2007-June 2009. Melena, hematemesis, hemafecia, and fecal occult bleeding were detected in the patients enrolled in this study. The duration of symptoms ranged 1 d-over 10 years. The main characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. All the patients were suspected of small bowel diseases. However, standard gastric and colonic endoscopy for them was negative. Other routine methods such as CT and small intestine radiography showed no exact diagnosis of etiology.

| Characteristics | n = 75 |

| Age (yr) | 51.5 ± 16.6 (16-86) |

| Sex (male/female) | 37/38 |

| Causes of OGIB | |

| Melena | 45 (60.0) |

| Hematemesis and melena | 7 (15.6) |

| Hemafecia | 17 (22.7) |

| Occult bleeding | 6 (8.0) |

| Duration of symptoms (mo) | |

| < 1 | 29 (38.7) |

| 1-12 | 24 (32.0) |

| > 12 | 22 (29.3) |

OGIB was detected in patients using a Fujinon enteroscope (EN450-P5/20, Fujinon Inc, Saitama, Japan) consisting of a mainframe, an enteroscope, an overtube and an air pump. Two soft latex balloons that can be inflated and deflated are attached to the tip of enteroscope and overtube. The balloons are connected to a pump through an air channel in the endoscope that can automatically modulate the air according to the different balloon pressures. By utilizing the overtube in combination with serial inflation and deflation of the balloons, endoscope can be inserted into the small bowel.

The patients were fasted overnight and 2 boxes of polyethylene glycol electrolyte mixed with 3000 mL water were taken 4-5 h prior to DBE through anus or mouth. At the same time, 5-10 mg of midazolam and 10 mg of scopolamine butylbromide were also injected intramuscularly 10 min before DBE. The patients were anaesthetized with 10 mL of oral 2% lidocaine hydrochloride before DBE through mouth. Oxygen was inhaled with electrocardiography monitored when necessary.

DBE through mouth or anus was performed according to the suspected site of lesions. When the site was uncertain, DBE was performed through mouth.

DBE was not performed when the cause of bleeding could be explained, the operation time was too long to be tolerated, and more than half of the small intestine examined was negative.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 11.5. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Difference was detected by χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

DBE was performed 84 times in 75 patients, including 57 times through mouth and 27 through anus. Two patients completed DBE of the entire small bowel through mouth at one time.

All the procedures were successful without anesthesia. No hemorrhage, perforation, acute pancreatitis or other serious complications occurred. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain occurred in some patients during the procedure. However, these symptoms were transient and tolerable. In general, DBE through anus was more tolerable than through mouth.

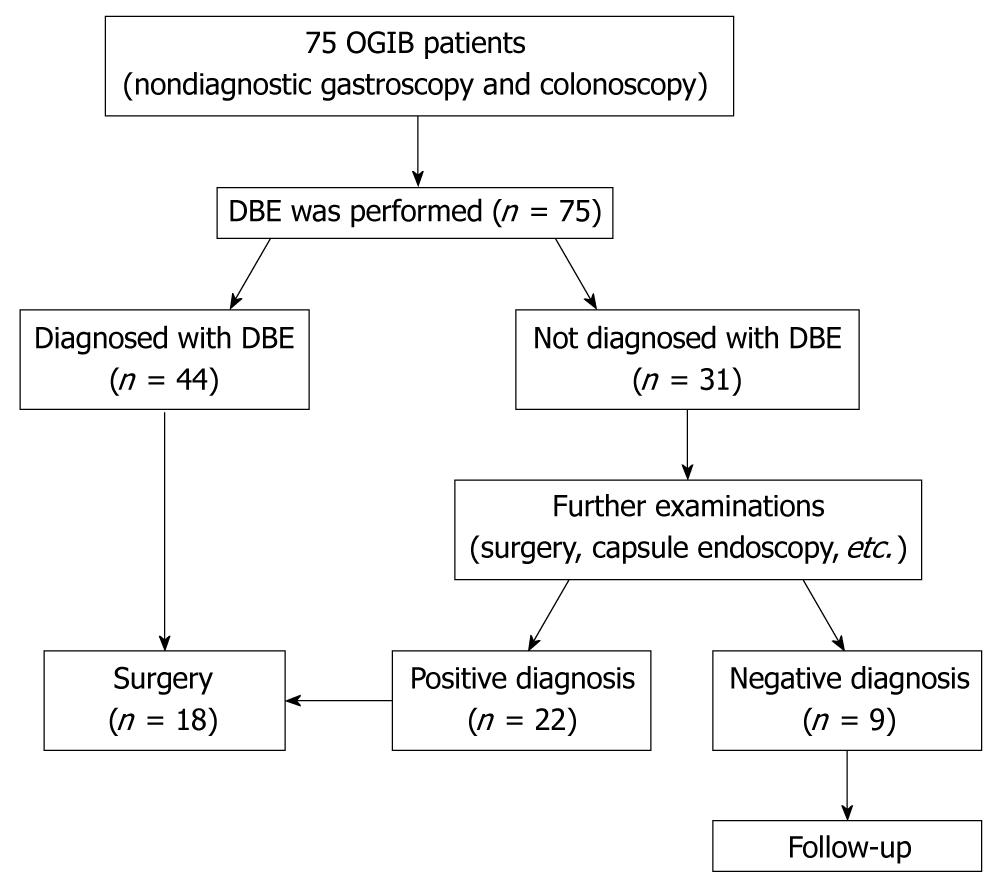

Of the 75 patients, 44 (58.7%) had positive DBE, 22 had negative DBE with potential bleeding sites observed at surgery and CE, etc. The distribution of OGIB patients enrolled in this study is shown in Figure 1. Among the 66 cases with positive DBE, OGIB was detected in upper digestive tract of 7 cases, in jejunum of 34 cases, in ileum of 24 cases, and at junction of jejunum and ileum of 1 case, respectively. The incidence of OGIB was higher in proximal small bowel (the third and fourth parts of duodenum, jejunum) than in distal small bowel (ileum) (49.3% vs 33.3%, P = 0.047). The DBE findings are presented in Table 2.

| Lesion | Diagnosed by DBE | Diagnosed by other methods | Location | Difference in proximal and distal small bowel | ||

| Stomach and duodenum | Jejunum | Ileum | ||||

| Tumor | 17 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 66.7% vs 19.0% (P = 0.002) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 7 | 12 | 1 | 62 | 1 | |

| Non-hodgkin lymphoma | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lipoma | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Brunner adenoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | |

| Angioma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Angiodysplasia | 7 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 64.3% vs 28.6% (P = 0.128) |

| Crohn’s disease | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 33.3% vs 66.7% (P = 0.132) |

| Diverticulum | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | 41 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 2 | |

| Single ulcer | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Others | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Un-diagnosed | 0 | 9 | - | - | - | |

| Total | 45 | 32 | 7 | 36 | 24 | 49.3% vs 33.3% (P = 0.047) |

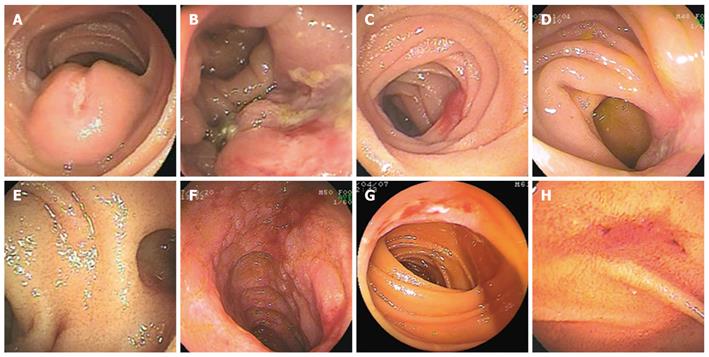

OGIB was most commonly caused by small bowel tumor (28.0%, 21/75), angiodysplasia (18.7%, 14/75) and Crohn’s disease (10.7%, 8/75). Small bowel tumor was detected in duodenum of 3 cases, in jejunum of 14 cases, and in ileum of 4 cases, respectively. The incidence of small bowel tumor was higher in jejunum than in ileum (66.7% vs 19.0%, P = 0.002). Histological analysis showed that the tumor was benign in 7 cases (gastrointestinal stromal tumor in 2, lipoma in 3, duodenum adenoma in 1 and angioma in 1) and malignant in 14 cases (gastrointestinal stromal tumor in 6, non-hodgkin lymphoma in 5 and adenocarcinoma in 3) (Figure 1). The detection rate of benign tumor was lower than that of malignant tumor (33.3% vs 66.7%, P = 0.031).

Angiodysplasia was detected in jejunum of 9 cases, in ileum of 4 cases, and in dieulafoy of gastric fundus of 1 case, respectively, accounting for 18.7% of all the cases with no significant difference between them (P = 0.128). Crohn’s disease was detected in jejunum and ileum of 2 and 6 cases, respectively, accounting for 10.7% of all the cases with no significant difference (P = 0.132). In addition, diverticulum, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, single ulcer, polyp, ancylostomiasis, tuberculosis, and non-specific inflammation were also detected (Figure 2).

Of the 75 cases, 45 presented with melena and 25 (55.6%) with positive DBE. Symptoms of hemafecia were detected in 17 cases with a DBE detection rate of 47.1% (8/17). There was no significant difference between the DBE detection rates of melena and hemafecia (55.6% vs 47.1%, P = 0.55). The DBE detection rates of occult bleeding, hematemesis and melena were not compared because of the limited number of cases.

The 75 patients were divided into 3 groups according to their bleeding time. There was no significance between the duration of OGIB symptoms and the DBE detection rates (Table 3).

Of the 75 patients, 18 (24.0%) underwent operation. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, non-hodgkin lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, lipoma and angioma were the most commonly detected tumors. Both gastrointestinal stromal tumor and bleeding from heterotopic pancreas were detected in 1 patient.

OGIB is a common problem encountered by gastroenterologists. Its diagnostic rate has been greatly improved due to CE since 2000[9]. CE has a higher diagnostic rate of OGIB than conventional methods including small bowel barium radiography, push enteroscopy, and cross-sectional imaging[10]. However, CE may fail to identify lesions such as Meckel’s diverticulum, angiodysplasia, and malignancies[11]. DBE can explore a large part of the small bowel, during which targeted tissue for biopsy can be taken. Moreover, endoscopic treatment procedures, including hemostasis, polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, balloon dilation, and stent placement, can be performed at DBE[12].

In this study, the diagnostic value of DBE for OGIB was evaluated. The DBE detection rate of OGIB is consistent with the reported data[13,14]. No complication occurred in the 75 patients who underwent DBE without anesthesia, suggesting that DBE is a safe, tolerable, and effective procedure for the diagnosis of OGIB.

It was reported that 3%-6% of OGIB events are caused by small bowel tumor[15,16]. Sun et al[17] showed that the prevalence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor is the highest among different small bowel tumors. DBE can show lesions in about 50%-66% of the small intestine and even in the entire small intestine, thus providing a high diagnostic rate of small bowel tumor[18].

In this study, angiodysplasia was found to be another common etiology of OGIB, which is also in agreement with the reported data[19]. The detection rate of lesions was higher in jejunum than in ileum. Since Crohn’s disease has been found to be the third commonest etiology of OGIB, and shows a higher incidence in distal intestine, DBE via anus is usually recommended[20].

The selection of DBE is still controversial. For those with no site of lesion indicated, DBE through mouth is preferred because our study and other studies showed that it has a higher diagnostic rate of lesions in proximal small bowel[21,22] and is relatively easier to perform without twisting the colon, which is also supported by Safatle-Ribeiro et al[23]. However, DBE through anus is also preferred by some endoscopists, since it has a better tolerance[18].

In summary, DBE is a safe, tolerable, accurate and effective procedure for the diagnosis of OGIB. OGIB is most commonly caused by small bowel tumor and angiodysplasia. Lesions occur more frequently in proximal small bowel and DBE through mouth is recommended as a prior consideration if no evidence indicates the location.

The diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) was rather difficult in the past. Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) and capsule endoscopy (CE) have significantly revolutionized the diagnosis of small bowel lesions. Compared with CE, DBE has unique advantages such as handing controllability, biopsy, diagnosis and treatment, etc. Few data are available on the diagnostic value of DBE for OGIB.

The data about 75 OGIB patients were retrospectively analyzed in this article. The DBE detection rate of OGIB and the feasibility of operation were evaluated. The incidence of common diseases in small bowel was compared. The DBE detection rate of lesions in proximal or distal small bowel was different.

Patients could tolerate the whole DBE process with no serious complication. The DBE detection rate of different bleeding events and symptoms of OGIB were compared. DBE through mouth was completed at one time.

In this study, DBE was proven to be a safe, accurate and effective procedure for the diagnosis of OGIB and can thus be performed in hospital for the diagnosis of OGIB.

OGIB is defined as recurrent or persistent gastrointestinal bleeding when gastric and colonic endoscopy is negative. DBE and CE are both new methods enabling diagnostic endoscopy of the entire small intestine, which have their own pros and cons in the diagnosis of small bowel diseases.

This is an interesting descriptive study concerning a single center experience with DBE for OGIB in China.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Francesco Manguso, MD, PhD, UOC di Gastroenterologia, AORN A. Cardarelli, Via A. Cardarelli 9, Napoli 80122, Italy; Dr. Albert J Bredenoord, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, St Antonius Hospital, PO Box 2500, 3430 EM, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands; Shmuel Odes, Professor, MD, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Soroka Medical Center, PO Box 151, Beer Sheva 84101, Israel

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:197-201. |

| 2. | Lewis BS. Small intestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:67-91. |

| 3. | Liu MK, Yu FJ, Wu JY, Wu IC, Wang JY, Hsieh JS, Wang WM, Wu DC. Application of capsule endoscopy in small intestine diseases: analysis of 28 cases in Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:425-431. |

| 4. | Girelli CM, Porta P, Malacrida V, Barzaghi F, Rocca F. Clinical outcome of patients examined by capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:148-154. |

| 5. | Rondonotti E, Villa F, Mulder CJ, Jacobs MA, de Franchis R. Small bowel capsule endoscopy in 2007: indications, risks and limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6140-6149. |

| 6. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. |

| 7. | Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Nakamura S, Iida M. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy with the double-balloon method in patients with obscure bleeding and polyposis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:827-832. |

| 8. | Wu CR, Huang LY, Song B, Yi LZ, Cui J. Application of double-balloon enteroscopy in the diagnosis and therapy of small intestinal diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:2075-2080. |

| 9. | Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4372-4378. |

| 10. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. |

| 11. | Li XB, Ge ZZ, Dai J, Gao YJ, Liu WZ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. The role of capsule endoscopy combined with double-balloon enteroscopy in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:30-35. |

| 12. | Kita H, Yamamoto H, Yano T, Miyata T, Iwamoto M, Sunada K, Arashiro M, Hayashi Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Double balloon endoscopy in two hundred fifty cases for the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disorders. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:74-77. |

| 13. | Nakamura M, Niwa Y, Ohmiya N, Miyahara R, Ohashi A, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Goto H. Preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Endoscopy. 2006;38:59-66. |

| 14. | Heine GD, Hadithi M, Groenen MJ, Kuipers EJ, Jacobs MA, Mulder CJ. Double-balloon enteroscopy: indications, diagnostic yield, and complications in a series of 275 patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:42-48. |

| 15. | Pilleul F, Penigaud M, Milot L, Saurin JC, Chayvialle JA, Valette PJ. Possible small-bowel neoplasms: contrast-enhanced and water-enhanced multidetector CT enteroclysis. Radiology. 2006;241:796-801. |

| 16. | Delvaux M, Fassler I, Gay G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1067-1073. |

| 17. | Sun B, Rajan E, Cheng S, Shen R, Zhang C, Zhang S, Wu Y, Zhong J. Diagnostic yield and therapeutic impact of double-balloon enteroscopy in a large cohort of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2011-2015. |

| 18. | Yamamoto H, Kita H, Sunada K, Hayashi Y, Sato H, Yano T, Iwamoto M, Sekine Y, Miyata T, Kuno A. Clinical outcomes of double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small-intestinal diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1010-1016. |

| 19. | Schäfer C, Rothfuss K, Kreichgauer HP, Stange EF. Efficacy of double-balloon enteroscopy in the evaluation and treatment of bleeding and non-bleeding small bowel disease. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:237-243. |

| 20. | Mehdizadeh S, Han NJ, Cheng DW, Chen GC, Lo SK. Success rate of retrograde double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:633-639. |

| 21. | Descamps C, Schmit A, Van Gossum A. "Missed" upper gastrointestinal tract lesions may explain "occult" bleeding. Endoscopy. 1999;31:452-455. |

| 22. | Hayat M, Axon AT, O'Mahony S. Diagnostic yield and effect on clinical outcomes of push enteroscopy in suspected small-bowel bleeding. Endoscopy. 2000;32:369-372. |

| 23. | Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Kuga R, Ishida R, Furuya C, Ribeiro U Jr, Cecconello I, Ishioka S, Sakai P. Is double-balloon enteroscopy an accurate method to diagnose small-bowel disorders? Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2231-2236. |