Published online Mar 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1548

Revised: January 18, 2010

Accepted: January 25, 2010

Published online: March 28, 2010

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is a congenital vascular anomaly characterized by a triad of varicose veins, cutaneous capillary malformation, and hypertrophy of bone and (or) soft tissue. Gastrointestinal vascular malformations in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome may present with gastrointestinal bleeding. The majority of patients with spleenic hemangiomatosis and/or left inferior vena cava are asymptomatic. We herein report a case admitted to the gastroenterology clinic with life-threatening hematochezia and symptomatic iron deficiency anemia. Due to the asymptomatic mild intermittent hematochezia, splenic hemangiomas and left inferior vena cava, the patient did not seek any help for gastrointestinal bleeding until his admittance to our department for evaluation of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. He was referred to angiography because of his serious pathogenetic condition and inefficiency of medical therapy. The method showed that hemostasis was successfully achieved in the hemorrhage site by embolism of corresponding vessels. Further endoscopy revealed vascular malformations starting from the stomach to the descending colon. On the other hand, computed tomography revealed splenic hemangiomas and left inferior vena cava. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome case presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding, splenic hemangiomas and left inferior vena cava. The literature on the evaluation and management of this case is reviewed.

- Citation: Wang ZK, Wang FY, Zhu RM, Liu J. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome with gastrointestinal bleeding, splenic hemangiomas and left inferior vena cava. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(12): 1548-1552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i12/1548.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1548

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare congenital disorder of the vascular system and is characterized by the following triad of clinical signs. (1) Haemangiomas due to cutaneous capillary dysplasias; (2) Soft tissue and/or bone hypertrophy; and (3) Venous and lymphatic anomalies[1]. At least two signs are present to establish the diagnosis[2,3].

Although seemingly uncommon, vascular malformations involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract have been reported and can be a source of significant morbidity and even mortality[1]. Clinical manifestations range from occult to massive, life-threatening hemorrhage. KTS patients with clinically significant hemorrhage usually require resection of the involved bowel segment[1]. Visceral vascular malformations in KTS have been described involving organs such as the GI tract, liver, spleen, bladder, kidney, lung and heart[4]. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis provides a simple, noninvasive means of assessing visceral hemangiomatous masses[5].

The left inferior vena cava (IVC) in KTS has not been reported. The left inferior vena cava does not affect the blood circulation, so these patients have no symptoms. They are accidentally discovered by abdominal CT imaging.

We herein report the clinical presentation and management of a young male patient with the diagnosis of KTS.

A 19-year-old male patient was admitted to the Gastroenterology Clinic for management of life-threatening hematochezia and symptomatic iron deficiency anemia. When he was born, there was a few vascular malformations in his body and right leg. The lesion on body surface was enlarged along with his age. As the lesion limits the right leg, exeresis was performed. The pathological section revealed well-marked capillary and arteriolar proliferation in the epidermal layer. The patient had been frequently admitted to the emergency unit due to transfusion-dependent anemia caused by mild intermittent hematochezia since July 2003. But he did not seek any help for gastrointestinal bleeding. Afterwards, the mild intermittent hematochezia continued and the amount of gastrointestinal bleeding increased over time. He was admitted to our hospital for evaluation after a severe and debilitating attack of hematochezia.

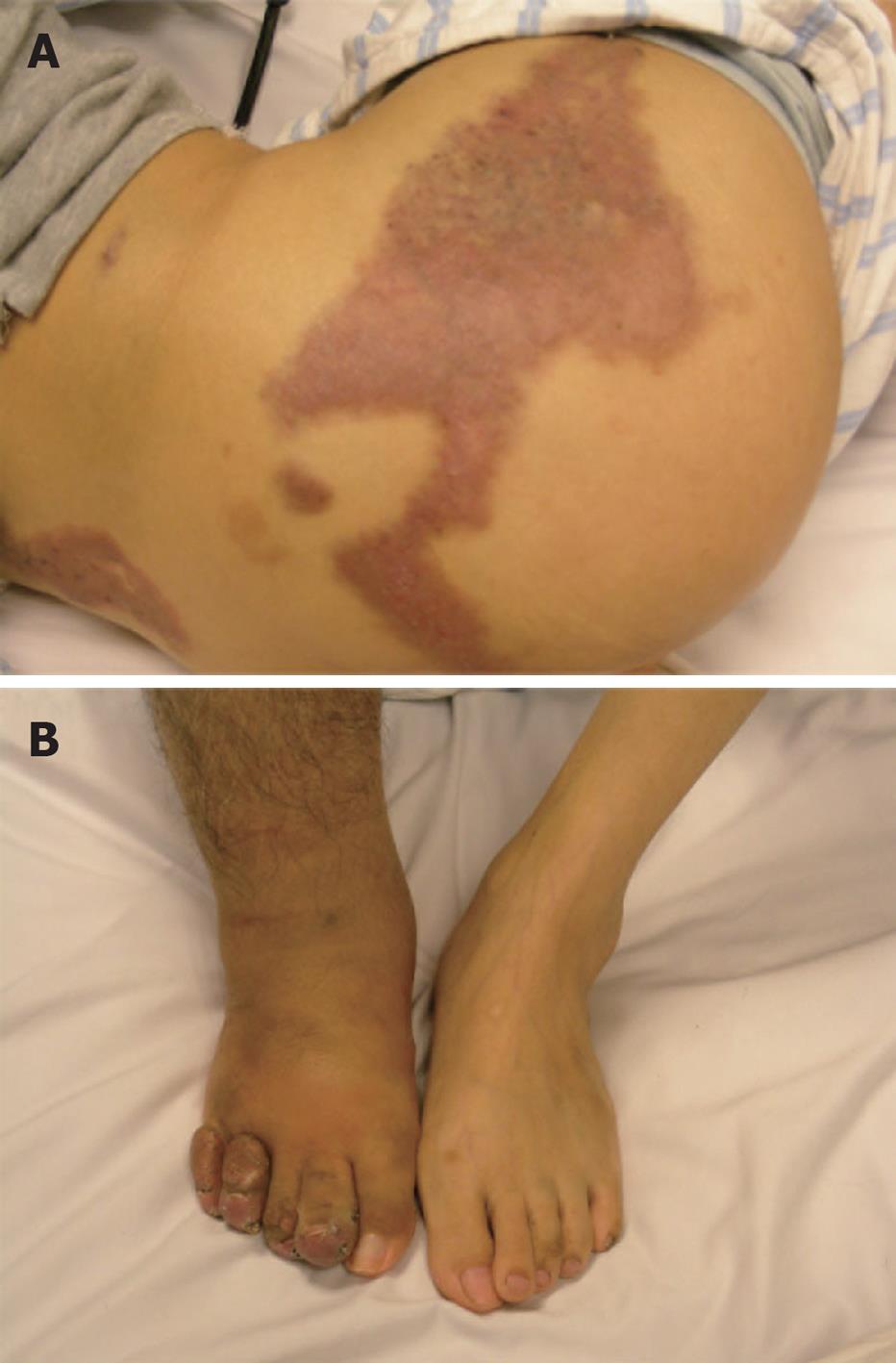

Physical examination revealed that his skin was pale, and there were several vascular malformation lesions on the surface of his body (Figure 1A) and a giant scar at the lateral right knee joint, and the right leg was obviously thicker than the left (Figure 1B). Laboratory examination showed significant anemia with hemoglobin of 2.2 g/dL, hematocrit 8.9%, iron 2.8 μmol/L, and total iron binding capacity 98 μmol/L. The platelet count and coagulation parameters were normal.

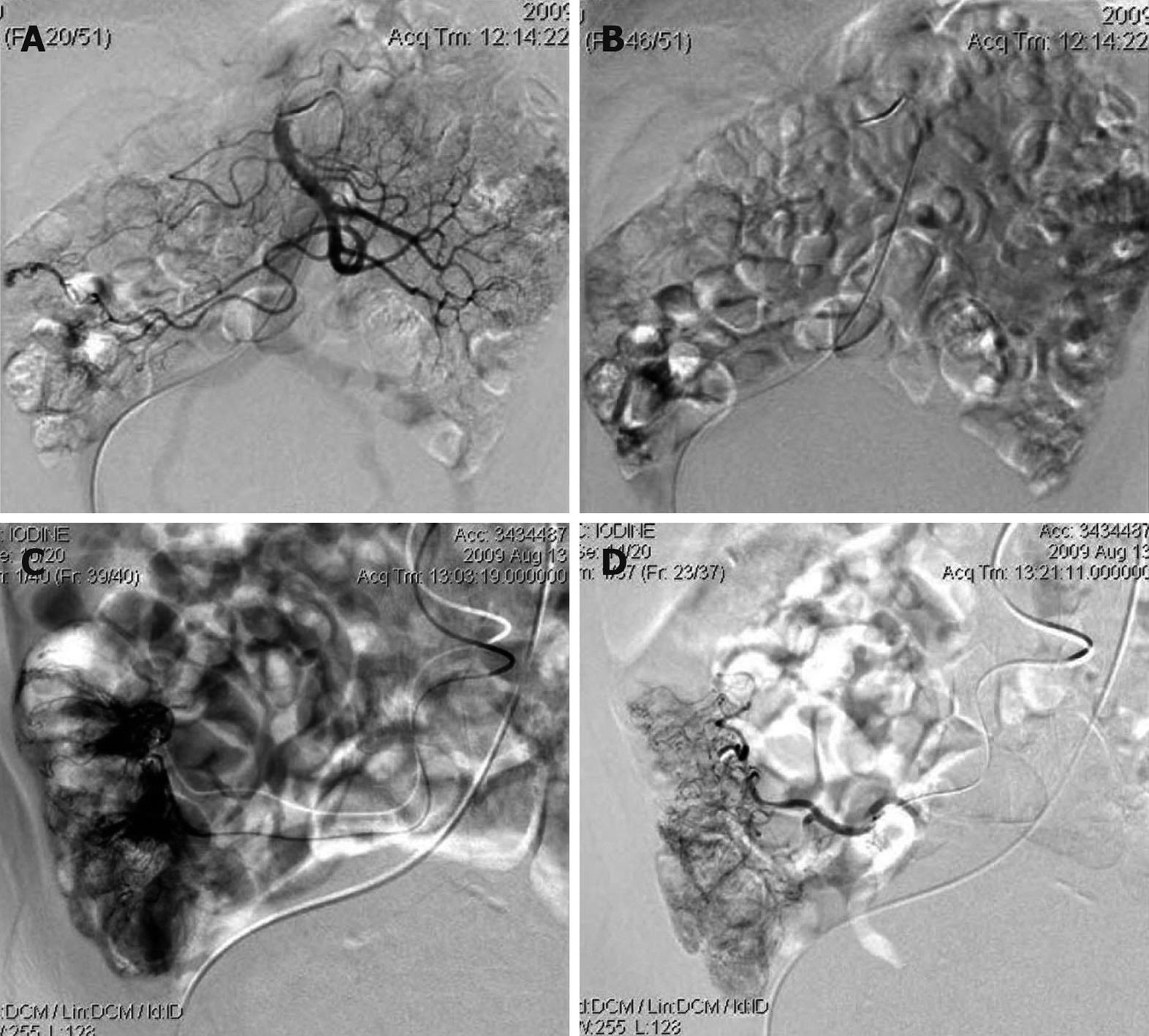

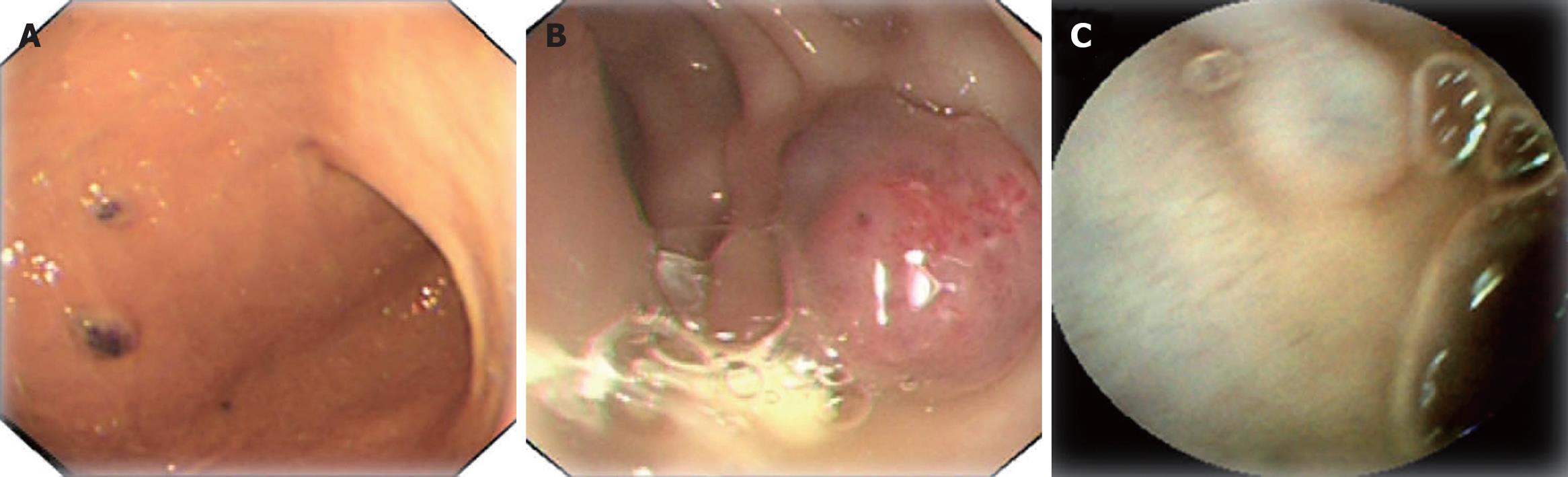

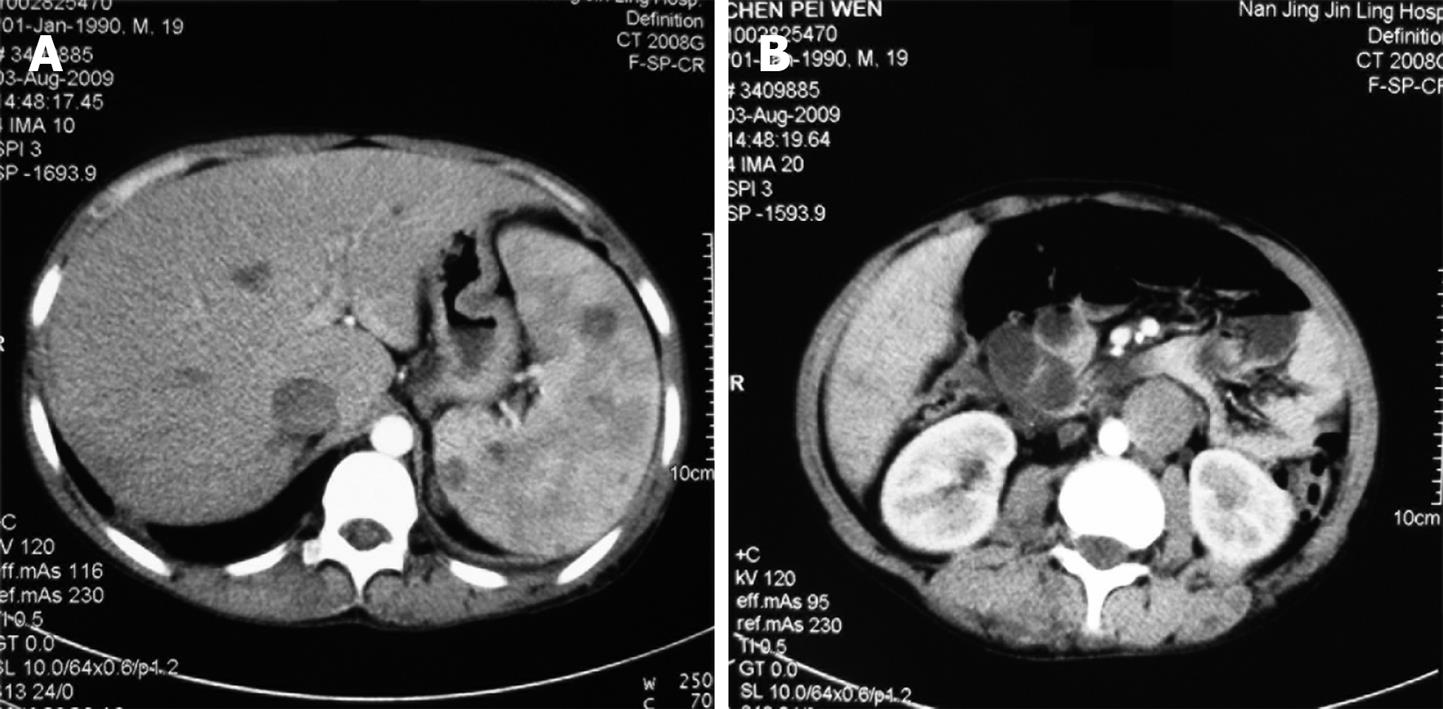

We could not obtain hemostasis by medical treatment. During hospitalization, the patient had an attack of massive hematochezia with loss of consciousness. Due to the severe symptomatic anemia and increased amount of GI bleeding over time, interventional examination and therapy were considered. The digital subtraction angiography revealed the bleeding point was caused by vascular malformation at terminal ileum. Superselective vessel embolism was performed (Figure 2). The patient had never hemorrhaged since the treatment. Further endoscopic investigation was conducted (Figure 3). Gastroscopy revealed several vascular malformation lesions at gastric antrum and gastric corpus. Colonoscopy revealed that there were several vascular malformation lesions from terminal ileum to the decending colon. Several vascular malformation lesions were found distributed from jejunum to ileum on the capsule endoscopy. Abdominal CT imaging showed left IVC and multiple hemangiomas in the spleen (Figure 4). Based on the vascular malformations in GI, splenic hemangiomas, cutaneous vascular malformation and the enlarged right leg, the patient was diagnosed as having KTS.

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is a term used to describe the combination of a cutaneous capillary malformation, varicose veins, and hypertrophy of bone and/or soft tissue. Most cases of KTS are sporadic, the syndrome affects males and females equally, has no racial predilection, and manifests at birth or during childhood[4].

Involvement of the GI tract may be more common in KTS than previously believed (occurring in perhaps as many as 20% of patients) and may be unrecognized in patients without symptoms[6]. The most common bleeding sites in the GI system are the distal colon and rectum. Jejunal vascular malformation and esophageal varices as bleeding sources caused by prehepatic portal hypertension were reported in the literature[1]. It is rare that the vascular malformation distributes in the whole GI. The spectrum of the GI bleeding may vary from asymptomatic occult bleeding to life-threatening massive bleeding. GI hemorrhage usually begins in the first decade of life and tends to be intermittent. Investigation of GI bleeding should begin with endoscopic examination in a patient with suspected KTS. Although endoscopy has the advantage of showing the localization and extension of vascular malformations, it might be misleading to accuse the vascular malformations observed during the endoscopy for bleeding due to possible metachromic localizations of vascular malformations in the different parts of the GI tract. With this point of view, endoscopic investigation of the entire GI tract should be made as the routine clinical practice for the exact localization and effective management of GI bleeding in patients with KTS. With the unawareness of this rare diagnosis, biopsies over the vascular malformations may be taken, which might be fatal in a patient with hematochezia[7]. On the other hand, the patient could not tolerate the endoscopy during the onset of serious hematochezia. So the interventional examination and therapy are ideal method at this time. First, advantages of angiography include the lack of requirement for bowel preparation. Secondly, angiography remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of vascular malformation. Following injection of contrast, vascular malformation can be recognized by ectatic slow-emptying veins, vascular tufts, or small veins that were filled earlier. Angiography is able to localize the bleeding source (when one is identified). Third, there is possibility of therapeutic intervention in some cases. Haemostasis can be achieved by intra-arterial infusion of vasopressin or arterial embolization via the angiographic catheter[8].

Hemangioma is the most common benign primary tumor of the spleen. Splenic hemangiomas may occur in a part of generalized angiomatosis as KTS. Complications of the splenic hemangiomas include rupture, hypersplenism, and malignant degeneration. The exact course for a given hemangioma is difficult to predict. Larger tumors (> 4 cm) are likely to be more prone to rupture than smaller ones, either spontaneously or from minor trauma, and may result in fatal hemorrhage. Spontaneous rupture has been reported as the most common complication, occurring in 25% of patients having large (> 4 cm) hemangiomas[9]. Recent reviews in adult patients reported that asymptomatic patients with small splenic hemangioma (< 4 cm) have been managed conservatively with observation, and no rupture or other complications occurred[10]. Kasabach-Merritt syndrome has been reported in patients with large hemangiomas[11]. As our patient was asymptomatic with splenic hemangiomas < 4 cm, a conservative approach with observation was preferred and splenectomy was not performed.

A left IVC results from regression of the right supracardinal vein with persistence of the left supracardinal vein. The prevalence is 0.2%-0.5%[12]. Typically, the left IVC joins the left renal vein, which crosses anteriorly to the aorta in the normal fashion, uniting with the right renal vein to form a normal right-sided prerenal IVC. The major clinical significance of this anomaly is the potential for misdiagnosis as left-sided para-aortic adenopathy[13]. In addition, spontaneous rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm into a left IVC has been reported[14]. The presence of vascular and renal anatomical anomalies may induce technical problems during abdominal aortic surgery[15-17] and may give rise to serious intraoperative complications. Therefore, prior to aortic surgery, preoperative knowledge of the presence of such anomalies helps with operative planning and may reduce the associated risk of major venous hemorrhage[15]. Abdominal CT is the most accurate investigation to discover such anomalies[16].

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of KTS is wide and can include additional arterial and lymphatic system abnormalities beyond the classical manifestation[18]. The potential of KTS to have widespread venous malformations in any part of the body implies that heterogeneous genetic mutations affecting mesodermal development may be present in patients with KTS[19]. At present, molecular diagnosis for KTS is not available. In conclusion, KTS is a rare condition with protean manifestations. Hematochezia should alert the physicians about the possibility of associated vascular malformations in the GI systems. Due to the progressive nature and wide extension of KTS lesions, endoscopic therapies have limited value in the management. Angiographic interventions should be used for visualizing the vascular anatomy and determining the disease extent. It is efficient to embolize the bleeding spots based on the examinations.

Peer reviewer: Spilios Manolakopoulos, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, 2nd Department of Internal Medicine, University of Athens, 3 Vironos Street, Agia Paraskevi, Athens 15343, Greece

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Wilson CL, Song LM, Chua H, Ferrara M, Devine RM, Dozois RR, Nehra V. Bleeding from cavernous angiomatosis of the rectum in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: report of three cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2783-2788. |

| 2. | Tsaridis E, Papasoulis E, Manidakis N, Koutroumpas I, Lykoudis S, Banos A, Sarikloglou S. Management of a femoral diaphyseal fracture in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:8852. |

| 3. | Lee A, Driscoll D, Gloviczki P, Clay R, Shaughnessy W, Stans A. Evaluation and management of pain in patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: a review. Pediatrics. 2005;115:744-749. |

| 4. | Jacob AG, Driscoll DJ, Shaughnessy WJ, Stanson AW, Clay RP, Gloviczki P. Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome: spectrum and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:28-36. |

| 5. | Yeoman LJ, Shaw D. Computerized tomography appearances of pelvic haemangioma involving the large bowel in childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:414-416. |

| 6. | Cha SH, Romeo MA, Neutze JA. Visceral manifestations of Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome. Radiographics. 2005;25:1694-1697. |

| 7. | Gandolfi L, Rossi A, Stasi G, Tonti R. The Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome with colonic hemangioma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:442-445. |

| 8. | Gomes AS, Lois JF, McCoy RD. Angiographic treatment of gastrointestinal hemorrhage: comparison of vasopressin infusion and embolization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:1031-1037. |

| 9. | Husni EA. The clinical course of splenic hemangioma with emphasis on spontaneous rupture. Arch Surg. 1961;83:681-688. |

| 10. | Willcox TM, Speer RW, Schlinkert RT, Sarr MG. Hemangioma of the spleen: presentation, diagnosis, and management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:611-613. |

| 11. | Dufau JP, le Tourneau A, Audouin J, Delmer A, Diebold J. Isolated diffuse hemangiomatosis of the spleen with Kasabach-Merritt-like syndrome. Histopathology. 1999;35:337-344. |

| 12. | Phillips E. Embryology, normal anatomy, and anomalies. Venography of the inferior vena cava and its branches. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins 1969; 1-32. |

| 13. | Siegfried MS, Rochester D, Bernstein JR, Miller JW. Diagnosis of inferior vena cava anomalies by computerized tomography. Comput Radiol. 1983;7:119-123. |

| 14. | Nishibe T, Sato M, Kondo Y, Kaneko K, Muto A, Hoshino R, Kobayashi Y, Yamashita M, Ando M. Abdominal aortic aneurysm with left-sided inferior vena cava. Report of a case. Int Angiol. 2004;23:400-402. |

| 15. | Giordano JM, Trout HH 3rd. Anomalies of the inferior vena cava. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:924-928. |

| 16. | Nishimoto M, Hasegawa S, Asada K, Furubayashi K, Sasaki S. The right retroperitoneal approach on abdominal aortic aneurysm with an isolated left-sided inferior vena cava. Report of a case. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2002;43:241-243. |

| 17. | Sonneveld DJ, Van Dop HR, Van der Tol A. Resection of abdominal aortic aneurysm in a patient with left-sided inferior vena cava and horseshoe kidney. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1999;40:421-424. |

| 18. | Vicentini FC, Denes FT, Gomes CM, Danilovic A, Silva FA, Srougi M. Urogenital involvement in the Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Treatment options and results. Int Braz J Urol. 2006;32:697-703; discussion 703-704. |