Published online Feb 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.996

Revised: February 8, 2009

Accepted: February 1, 2009

Published online: February 28, 2009

AIM: To analyze the influence of human immunode-ficiency virus (HIV) infection on the course of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

METHODS: We performed a meta-analysis to quantify the effect of HIV co-infection on progressive liver disease in patients with HCV infection. Published studies in the English or Chinese-language medical literature involving cohorts of HIV-negative and -positive patients coinfected with HCV were obtained by searching the PUBMED, EMBASE and CBM. Data were extracted independently from relevant studies by 2 investigators and used in a fixed-effect meta analysis to determine the difference in the course of HCV infection in the 2 groups.

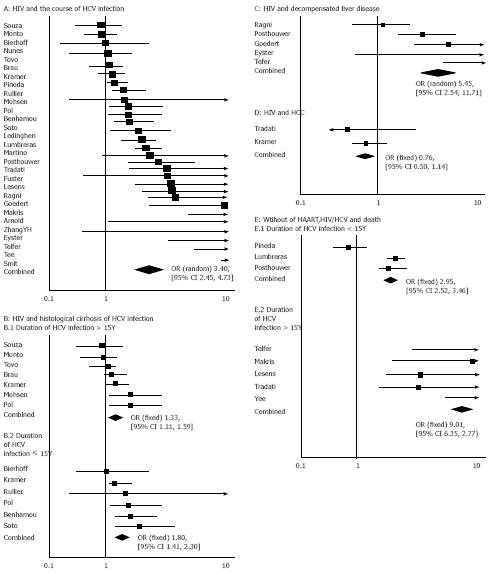

RESULTS: Twenty-nine trails involving 16 750 patients were identified including the outcome of histological fibrosis or cirrhosis or de-compensated liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma or death. These studies yielded a combined adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.40 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.45 and 4.73]. Of note, studies that examined histological fibrosis/cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma or death had a pooled OR of 1.47 (95% CI = 1.27 and 1.70), 5.45 (95% CI = 2.54 and 11.71), 0.76 (95% CI = 0.50 and 1.14), and 3.60 (95% CI = 3.12 and 4.15), respectively.

CONCLUSION: Without highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART), HIV accelerates HCV disease progression, including death, histological fibrosis/cirrhosis and decompensated liver disease. However, the rate of hepatocellular carcinoma is similar in persons who had HCV infection and were positive for HIV or negative for HIV.

- Citation: Deng LP, Gui XE, Zhang YX, Gao SC, Yang RR. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(8): 996-1003

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i8/996.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.996

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem, with an estimated global prevalence of 3% occurring in about 170 million infected persons worldwide. The natural history of HCV infection remains controversial because there is a considerable variability in the published estimates of the time span over which cirrhosis develops, as well as the proportion and characteristics of persons in whom it occurs. In common, the natural history of HCV infection remains including acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensated liver disease and death. Approximately 75%-85% of infected patients do not clear the virus for 6 mo, and chronic hepatitis develops. An estimated 5%-20% of HCV-infected patients have or will develop cirrhosis, and 1%-4% of them will annually develop hepatocellular carcinoma. The disease progress of HCV infection may be affected by many factors, including the age of infection, gender, ethnicity, duration of infection, alcohol consumption, mode of acquisition, and immunosuppression[1].

Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HCV, a major public health problem, frequently shares the blood, sexual, and mother-to-child routes of transmission[2–4]. It is estimated that 4-5 million patients are coinfected with HIV and HCV in the world[5]. The prevalence of HIV-HCV coinfection is even up to 90% in persons injecting drugs[6].

Before an introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART), the impact of HCV on the course of HIV infection is overshadowed by extrahepatic cause of death, related to immunodeficiency factors, namely opportunistic infection, lymphomas or wasting syndrome. The development of HAART results in a significant decrease in morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected patients. HCV is the leading non-AIDS cause of death in coinfected persons[7–9]. There is convincing evidence that coinfection with HIV worsens the prognosis of HCV-related liver disease. It was reported that persons coinfected with HIV and HCV would develop cirrhosis, and the incidence of end-stage liver disease is higher in HCV-infected individuals[1011], especially in individuals with CD4 < 200 cells/&mgr;L and alcohol consumption[12]. Graham performed a meta-analysis of eight studies in 2001 to examine the risk of cirrhosis and ESLD in individuals coinfected with HIV and HCV and infected with only HCV, and found that the risk of progressing to cirrhosis and liver failure in individuals coinfected with HIV and HCV is two-fold and six-fold higher, respectively, than in those infected with only HCV[13]. However, this study did not compare the end-point event of death between the two groups. Since then, a large number of cohort studies showing the effect of HIV on liver disease progression have been published. Based on the above data, we conducted a meta-analysis of published studies to investigate the impact of HIV coinfection on the course of HCV, decompensated liver disease, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and death.

The aim of this analysis was to summarize the main characteristics of the included studies in order to provide a point estimate of the effect of HIV-HCV coinfection on progressive liver disease compared with HCV infection, to examine the potential heterogeneity, and to identify the potential confounding variables in these studies.

Using variations on the terms of human immunodefi-ciency virus, AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, hepatitis C, cohort study, death, end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic cirrhosis, and hepatic fibrosis, we conducted a search of the available studies published in English and Chinese from PUBMED, EMBASE and CBM from 1992 when HCV EIA became available to August 30, 2008 to show how concurrent HIV infection changes the course of hepatitis C infection. Combined key words were used to maximize the search results. The bibliographies of selected articles and reviews were also searched for pertinent studies.

All identified articles were screened, and we excluded articles that were determined to be irrelevant on the basis of a review of the title and/or abstract. Full texts of all remaining articles were retrieved and reviewed.

Only full-length and peer-reviewed original journal articles were included. Articles that did not provide the number of patients infected with HCV and HIV and clinical outcomes of liver disease were excluded. The remaining articles were independently examined in detail by at least 2 of the observers for the number of patients with HIV-HCV coinfection compared to those with only HCV infection. HCV infection was defined by a positive result of a second or third generation of HCV ELISA and confirmed by recombinant immunoblot assay or PCR. HIV infection was defined by a positive result of HIV ELISA and confirmed by Western blot assay. Patients selected for study did not exclude living patients to avoid bias against non-terminal severe liver disease. Outcomes included histopathological diagnosis of cirrhosis based on the criteria defined by Knodell et al[14] or clinically defined decompensated liver disease defined unambiguously as the presence of ≥ 2 of the following conditions: bleeding esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia not attributable to medications or hepatocellular carcinoma confirmed by ultrasonic or histopathological diagnosis, or mortality.

Quantitative data on the number of cohort subjects with HCV infection or HCV-HIV coinfection were extracted, and the number of patients in each infection group with the outcome of clinical decompensated liver disease or histological cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death was calculated. Contingency tables were created, and results were converted to odds ratio (OR). When risk estimates were presented, we used those adjusted for the greatest number of potential confounders.

Two independent reviewers abstracted each article separately. Where discrepancies arose, a third investigator arbitrated. When a report ≥ 1 appeared to describe the same cohort of patients (which was established based on the cohort location and authors involved), we selected the most recent or the most complete study.

Analyses were conducted with Review manager (version 4.2, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). We assessed the heterogeneity for each pooled estimate with Cochran’s Q test. We used a fixed-effect model because of the anticipated variability among trails regarding the different outcomes. The overall mean difference was estimated. The significance was measured at P < 0.05. Significant heterogeneity was measured at P < 0.10. In the event of significant heterogeneity, results were further analyzed with respect to the outcomes of trails, such as histopathological diagnosis of cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses omitting each study in turn to determine whether the results were influenced excessively by a single study.

After searching the PUBMED, EMBASE and CBM, a total of 422 studies were identified and screened for retrieval. Two hundred and ninety-seven case reports, case-control studies, or review articles were excluded. One hundred and twenty-five studies were collected for further review. Of these 125 studies, 96 were excluded due to lack of information on the progression of hepatitis C or lack of HCV infection control group. The remaining 29 studies[915–42] were included in the analysis (Figure 1A).

The general characteristics of these studies and their participating subjects are shown in Table 1. The number of patients participating in the studies ranged 55-2883. Their mean age was 21-50 years. Most patients were men. Of the 29 cohort studies, 13 were retrospective in design, 11 were prospective in design, and 1 was a cross-study in design, and 4 did not show the type of design. We evaluated data of 16 750 HCV-positive patients. Of them, 6242 were positive for HIV and 10508 were negative for HIV. Fourteen studies assessed the histological cirrhosis[918192127–3238394142], 7 studies assessed the death[17222334–3640], 3 studies assessed the decompensated liver disease[152637], 2 studies assessed the outcome of decompensated liver disease and death[1617–25], 1 study assessed the outcome of histological cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and death[20], 1 study assessed the outcome of histological cirrhosis and death[24], and 1 study assessed the outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma and death[33], respectively. Most studies did not provide a racial distribution. There was a similar variability in HCV viral load.

| Reference country | Years (data collected) | Study design | Characteristics of patients | Total Patients infected with HIV-/HIV+ | Duration of HCV infectionHIV+/HIV- (yr) | Outcome | Covariates |

| USA[15] | 1982-1991 | Prospective cohort | Hemophilia; mean age 23 yr (2-69), 93% males, 97% whites | 58/91 | 10-25 | Liver failure | Liver function, CD4 count, excluding positive HBsAg |

| UK[16] | 1979-1993 | Retrospective cohort | Hemophilia, mean age 34 yr | 109/74 | 15 | Death, DLD | Age, type of hemophilia, CD4, 2%HBsAg+ |

| UK[17] | 1968-1995 | Prospective cohort | Hemophilia, mean age 38.3 yr, 92% males, mean age of HCV infection 21 yr, follow-up time 28 yr | 102/36 | UK | Death | type of hemophilia, 2%HBsAg+, Pre-HAART |

| Italy[18] | 1989-1994 | Multicentre cohort | Voluntary liver biopsy patients; HIV-HCV coinfection, mean age 28 yr, 77% males, 97%IDU. HCV-infection: mean age 37 yr, 62% males, main routes of IDU and transfusion | 431/116 | 11.3/7.6 | Histological cirrhosis | Duration of HCV infection, HCV-VL, CD4, excluding alcohol, other hepatitis virus infection |

| Germany[19] | 1989-1995 | Retrospective | Voluntary liver biopsy patients; HIV-HCV coinfection, mean age 34 yr, 95% males. HCV-infection, :mean age 42 yr, 70% males | 33/22 | > 10 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Age, sex, CD4, 2 cases of HBsAg+ |

| Italy[20] | 1992- | Prospective Multicentre | Hemophilia, 98% males | 243/141 | > 20 | HCC, cirrhosis, death | Age, type of hemophilia |

| France[21] | UK | Retrospective | IDU, mean age 33 yr, 75% males, 35%Etoh | 150/60 | 11.8/12.3 | Histological cirrhosis | duration of HCV, 7.5%HBsAg+EtOH |

| Canada[22] | 1982-1998 | Prospective, cohort | Hemolphilia, mean age 22.2/19.7 yr | 53/81 | 17 | Death | Type of hemophilia |

| France[12] | 1995-1998 | Retrospective | Voluntary liver biopsy patients, 90%IDU, mean age 35.5 yr, 72% males | 122/122 | 13 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | pre-HAART era, 1 HBsAg+, Sex, Etoh, age of HCV infection, CD4, excluding HBsAg+ |

| UK[23] | 1985-1999 | Prospective | Hemophilia, mean age 17 yr | 185/125 | 17 | Death | HCV genotype, age of HCV infection, Etoh, 6 cases of HBsAg+ |

| France[24] | 1980-1995 | Retrospective | IDU, mean age 31 yr, 73% males, HIV+ group: 62%IFN treatment. HIV- group: 77% IFN treatment | 80/80 | 10.2/10.6 | Cirrhosis, death | Alcohol, HCV genotype |

| USA[25] | 1978-1999 | Prospective | Hemaphilia, 96.2% whites | 72/85 | UK | DLD, death | HbsAg, alcohol |

| Greece[26] | 1981-1987 | Prospective | Hemophilia, 90% males, most whites, mean age of HIV+ 21 yr, mean age of HIV-18yr | 624/1194 | UK | DLD | Age, alcohol consume, CD4 count, duration of HCV infection, 7% HBsAg+ |

| UK[27] | 1994-2002 | Retrospective | Voluntary liver biopsy patients, mean age 38.8 yr, 73% males, 77%IDU | 153/55 | 23/21 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Sex, age of HCV infection, Etoh, HAART, excluding HBV |

| Spain[28] | 1998-2001 | Cross-section | Voluntary liver biopsy patients, mean age 40 yr, 75% males, genotype 1, IDU 88% of positive HIV, 88%HIV with ARV treatment | 75/75 | UK | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Sex, age of HCV infection, HAART, HCV-VL, excluding alcohol, HBsAg |

| France[29] | 2000.4-2000.12 | Prospective | Most of IDU, mean age 38 yr, most of genotype 3 or 4, 67% males, 11% with alcohol consume | 33/33 | 15/14 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | HCV genotype, HCV-VL, CD4, HIV-VL, excluding alcohol, HBsAg |

| China[30] | 2001-2003 | Retrospective | CHC of inpatients, all blood transfusion. HIV+ group, :mean age 38 yr, 50% males. HIV-group 39yr, 39% males, pre-HAART era | 33/140 | < 15 | Clinical cirrhosis | CD4 count, excluding alcohol, HBsAg |

| USA[31] | 1997-2004 | UK | CHC, main genotype 1. IDU 76%. HIV+group: mean age 47 yr, 92% males, 15% alcohol consume. HIV-group: mean age 49 yr, 87% males, 31% alcohol consume | 372/92 | 24/22 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | HCV genotype, HCVVL, BMI, HIV-VL, CD4 count |

| USA[32] | UK | Prospective | Voluntary liver biopsy patients, main genotype 1, all IDU. HIV+ group: mean age 47 yr, 77% males. HIV-group: mean age 47 yr, 60% males, 83% with HAART | 57/40 | UK | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | HCV-VL, HCV genotype, CD4, HIV-VL |

| USA[33] | 1991-2000 | Retrospective | CHC with inpatients, mean age 45 yr, 97% males, 58% without HAART | 26641/4761 | UK | HC, HCC | HAART |

| Canada[34] | 1982-2003 | Cohort | Hemophilia, 98% pre-HAART era | 712/444 | UK | Death | Type of hemophilia |

| Spain[35] | 1997-2002 | Multicentre Retrospective | Patients with decompensated HCV-related cirrhosis, HIV-infected: mean age 38 yr, 86% males, 86% IDU, HCV genotype1 63%, HbsAg 24%. HIV-uninfected:mean age 66 yr, 58% males, HCV genotype1, 83% other sources of HCV infection. 91% HIV-infected patients with HAART | 1037/180 | 26/15 | Death | Age, HCV genotype, HCV-VL, excluding HBsAg |

| Spain[36] | 1990-2002 | Prospective | IDU, 77% males, follow-up time 8.6 yr | 1418/1465 | 9.6/13.5 | Death | Age, sex, HAART, HAART, 4.6% HbsAg+ |

| UK[37] | 1961-2005 | Multicentre | Hemophilia, mean age 43 yr, 94% males, HCV genotype1 53% | 497/190 | 27 | DLD | Age, alcohol consume, HCV genotype,HAART, 2.8%HBsAg+ |

| Zambia[38] | 2000-2004 | Retrospective | HIV-infected: mean age 38 yr, 76% males, 50% IDU. HIV-unifected: mean age 48 yr, 51% males, 31% blood transfusion. 91% HIV patients with HAART, time of HAART 3.6 yr | 247/162 | 19.8/15 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Age, sex, alcohol consume, HCV-VL, excluding HbsAg+ |

| USA[39] | 1999-2002 | Retrospective | HIV+ :mean age 45 yr, 80% males, 72% IDU. HIV-: mean age 48 yr, 79% males, 58% IDU. 79% genotype 1. 95% HIV patients with HAART. time of HAART 3.6 yr | 382/274 | 25/23 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Age, alcohol consume, HCV genotype, HCV-VL, CD4, HIV-VL, excluding HBsAg |

| Dutch[40] | 1985-2006 | Prospective | IDU, mean age 30 yr, 64% males, follow-up time 9 yr (5-14) | 565/256 | 8/10 | Death | HAART, CD4 |

| Zambia[41] | 2003-2004 | Retrospective | HIV+: mean age 40 yr, 79% males, 79% IDU. HIV-: mean age 46 yr, 45% males, 25% IDU | 65/53 | 18.7/20.6 | Histological fibrosis/cirrhosis | Liver function, HCV-VL, HCV genotype, CD4, excluding HbsAg, patients with DLD |

| France[42] | 2004-2006 | Retrospective | HIV+ mean age 43 yr, 67% males, 83% IDU HIV-: mean age 52 yr, 38% males, 45% blood transfusion; 88% HIV patients with HAART | 656/287 | 23.5/22.1 | Fibroscan of fibrosis/cirrhosis | Age, sex, BMI, HCV-subtype, HCV-VL, HIV-VL, CD4 count excluding HbsAg+, alcohol |

Studies in immunocompetent persons showed that the progression of chronic HCV infection is affected by many external and host factors, including duration of HCV infection, alcohol consumption, coinfection with other hepatitis viruses, etc. Other studies assessed the duration of hepatitis C except for 6 studies[25262832–34]. In these studies, HCV infection was typically assumed due to the exposure to clotting factor, blood transfusion, or initiation of injecting drugs. The mean duration of HCV infection ranged 10-28 years. In our analysis, 3 studies excluded patients who consumed alcohol excessively, 15 studies attempted to assess the significance of alcohol use by quantifying grams of alcohol consume per day, the other studies did not show alcohol consume of patients. Because of the various methods to describe alcohol consumption in these studies, this important factor could not be incorporated into further analyses. Twelve studies excluded patients with detectable hepatitis B surface antigen from their cohort, 4 studies did not describe the state of hepatitis B surface antigen in their cohort, the other 12 studies reported the number of patients with positive HBV surface antigen (Table 1).

Inclusion of all end points in studies: The combined unadjusted OR for the 29 studies was 3.40 (95% CI = 2.45 and 4.73) by the random effect model (Figure 1A and B). The test for heterogeneity was significant (P < 0.001). Since some factors led to the significant heterogeneity, including different outcomes of our analysis, duration of HCV infection, we also performed subgroup analyses determined a priori.

Analysis of the end points of histological cirrhosis and liver cancer: Seventeen studies assessed liver fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection and HCV infection. The outcome of cirrhosis in in studies was confirmed by histological diagnosis. All studies addressed the effect of duration of HCV infection on progression to severe liver disease. Since the test for heterogeneity had no statistical significance (P = 0.15), the fixed effect model was used for subsequent analyses. Thirteen studies examining the end point of histological cirrhosis had a pooled OR of 1.47 (95% CI = 1.27 and 1.70). Cirrhosis was stratified by duration of HCV infection in years. The combined OR for duration of HCV infection within 15 years was 1.80 (95% CI = 1.41 and 2.30) in 6 studies, whereas that for duration of HCV infection exceeding15 years was 1.33 (95% CI = 1.11 and 1.59) in 7 studies (Figure 1B). Five studies examined the end point of decompensated liver disease (DLD). The test for heterogeneity was significant (P = 0.008). The random effect model was used for subsequent analyses. The pooled OR for DLD was 5.45 (95% CI = 2.54 and 11.71, Figure 1C). Only 2 studies assessed the end point of hepatocellular carcinoma. The pooled OR for liver cancer was 0.76 (95% CI = 0.50 and 1.14, Figure 1D).

Analysis of end point of death: Eight studies assessed the end point of death in the two groups before HAART. The combined OR for the 8 studies was 3.60 (95% CI = 3.12 and 4.15) using the fixed effect model. Death was stratified by duration of HCV infection in years. The combined OR for duration of HCV infection within 15 years was 2.95 (95% CI = 2.52 and 3.46), whereas that for duration of HCV infection exceeding 15 years was 9.01(95% CI = 6.35 and12.77, Figure 1F).

Our meta-analysis quantitatively assessed the influence of HIV infection on the course of HCV infection. The overall OR for histological cirrhosis or decompensated liver disease or liver cancer or death was 3.40 (95% CI = 2.45 and 4.73) by the random effect model. However, these studies had a significant heterogeneity. Some factors could explain the heterogeneity, including different outcomes in these studies, methodological differences in study design, different number of patients in cohort, bias in selection of patients for biopsies, effect of duration of HCV infection on progression to severe liver disease, and publication bias.

We also performed subgroup analyses to determine the priority according to the different outcomes and duration of HCV infection. Striking differences were found in studies examining different end points of histological cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma or death. The combined adjusted OR for histological cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma and death was 1.47 (95% CI = 1.27 and 1.70), 5.45 (95% CI = 2.54 and 11.71), 0.76 (95% CI = 0.50 and 1.14), and 3.60 (95% CI = 3.12 and 4.15), respectively. There was a smaller difference between HIV-HCV coinfected and HCV-infected patients with regard to the development of cirrhosis or liver cancer, but there was a substantial increased risk of developing decompensated liver disease or death.

In the pre-HAART era, many patients coinfected with HIV and HCV died of opportunistic infection, lymphoma or wasting syndrome due to severe immunodeficiency, which is the main risk factor for death of HIV-HCV coinfection patients. The declined HIV-related mortality after widespread use of HAART parallels the emergence of HCV-related liver disease as an important cause of mortality in coinfected patients. Studies indicate that HAART has a protective effect on fibrosis progression in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection. On the other hand, HAART may enhance liver damage in some HIV-HCV coinfected individuals through drug-related hepatotoxicity. Only 6 studies[283235383942] in our analysis introduced the state of HAART in patients with HIV-HCV co-infection. The proportion of patients who were receiving HAART in cohort ranged 83%-95%. However, we could not acquire the primary data comparing progression of HCV infection in pre-HAART and HAART era, and the other studies were performed before the widespread use of HAART. We, therefore, did not examine the impact of HAART on the progression of HCV infection. This is an important limitation in our study and its impact on the progression of HCV-induced liver disease needs to be explored.

Other factors may have influenced the level of liver damage in HIV-HCV coinfected patients. Important fields for further study include the effects of HAART on HCV-related liver disease progression, duration of HCV infection, and alcohol consumption.

The results of our study suggest that HIV infection can significantly change the natural history of HCV infection, especially in the development of death or decompensated liver disease. Because most cohorts in our analysis were composed of patients with hemophilia or injection drugs, and most patients studied were males, caution should be taken in generalizing the results of this meta-analysis of women and racial or ethnic populations not represented in these studies. All these factors may potentially impact the natural history of HCV infection.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem. Coinfecion with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HCV frequently shares blood, sexual, mother-to-child routes of transmission. It is estimated that 4-5 million patients were coinfected with HIV and HCV in the world. HCV is the leading non-AIDS cause of death. A large number of cohort studies have examined the different impacts of HIV on HCV infection in terms of clinically unambiguous end points of decompensated liver disease and biopsy-proven cirrhosis.

Interaction of HIV and HCV is a hot spot. HIV infection can change the natural history of chronic hepatitis C with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis. HIV-related immunodeficiency may be a determinant factor for higher hepatitis C viremia levels and more severe liver damage.

This study analyzed the impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of HCV infection, and compared the clinically unambiguous end points of decompensated liver disease, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and death.

Meta-analysis suggests that HIV accelerates HCV disease progression, death, histological fibrosis/ cirrhosis and decompensated liver disease. However, the rate of hepatocellular carcinoma is similar in patients infected with HCV who are positive or negative for HIV. This has important implications for the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients coinfected with HCV and HIV.

This manuscript is reasonably well written and contains interesting information.

| 1. | Chen SL, Morgan TR. The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:47-52. |

| 2. | Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:831-837. |

| 3. | Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C in the HIV-Infected Person. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:197-207. |

| 4. | Thomas DL. Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Hepatology. 2002;36:S201-S209. |

| 5. | Tossing G. Management of chronic hepatitis C in HIV-co-infected patients--results from the First International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Co-infection, 2nd-4th December 2004, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10:43-45. |

| 6. | Verucchi G, Calza L, Manfredi R, Chiodo F. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection: epidemiology, natural history, therapeutic options and clinical management. Infection. 2004;32:33-46. |

| 7. | Bica I, McGovern B, Dhar R, Stone D, McGowan K, Scheib R, Snydman DR. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:492-497. |

| 8. | Monga HK, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Breaux K, Khattak K, Troisi CL, Velez M, Yoffe B. Hepatitis C virus infection-related morbidity and mortality among patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:240-247. |

| 9. | Pineda JA, Garcia-Garcia JA, Aguilar-Guisado M, Rios-Villegas MJ, Ruiz-Morales J, Rivero A, del Valle J, Luque R, Rodriguez-Bano J, Gonzalez-Serrano M. Clinical progression of hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients undergoing highly active antiretroviral therapy. Hepatology. 2007;46:622-630. |

| 10. | Martin-Carbonero L, Benhamou Y, Puoti M, Berenguer J, Mallolas J, Quereda C, Arizcorreta A, Gonzalez A, Rockstroh J, Asensi V. Incidence and predictors of severe liver fibrosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C: a European collaborative study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:128-133. |

| 11. | Ragni MV, Belle SH. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on progression to end-stage liver disease in individuals with hemophilia and hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1112-1115. |

| 12. | Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di Martino V, Charlotte F, Azria F, Coutellier A, Vidaud M, Bricaire F, Opolon P, Katlama C. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. The Multivirc Group. Hepatology. 1999;30:1054-1058. |

| 13. | Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, Mrus JM, Carnie J, Heeren T, Koziel MJ. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562-569. |

| 14. | Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431-435. |

| 15. | Eyster ME, Diamondstone LS, Lien JM, Ehmann WC, Quan S, Goedert JJ. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in multitransfused hemophiliacs: effect of coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus. The Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:602-610. |

| 16. | Telfer P, Sabin C, Devereux H, Scott F, Dusheiko G, Lee C. The progression of HCV-associated liver disease in a cohort of haemophilic patients. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:555-561. |

| 17. | Makris M, Preston FE, Rosendaal FR, Underwood JC, Rice KM, Triger DR. The natural history of chronic hepatitis C in haemophiliacs. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:746-752. |

| 18. | Soto B, Sanchez-Quijano A, Rodrigo L, del Olmo JA, Garcia-Bengoechea M, Hernandez-Quero J, Rey C, Abad MA, Rodriguez M, Sales Gilabert M. Human immunodeficiency virus infection modifies the natural history of chronic parenterally-acquired hepatitis C with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1-5. |

| 19. | Bierhoff E, Fischer HP, Willsch E, Rockstroh J, Spengler U, Brackmann HH, Oldenburg J. Liver histopathology in patients with concurrent chronic hepatitis C and HIV infection. Virchows Arch. 1997;430:271-277. |

| 20. | Tradati F, Colombo M, Mannucci PM, Rumi MG, De Fazio C, Gamba G, Ciavarella N, Rocino A, Morfini M, Scaraggi A. A prospective multicenter study of hepatocellular carcinoma in italian hemophiliacs with chronic hepatitis C. The Study Group of the Association of Italian Hemophilia Centers. Blood. 1998;91:1173-1177. |

| 21. | Pol S, Lamorthe B, Thi NT, Thiers V, Carnot F, Zylberberg H, Berthelot P, Brechot C, Nalpas B. Retrospective analysis of the impact of HIV infection and alcohol use on chronic hepatitis C in a large cohort of drug users. J Hepatol. 1998;28:945-950. |

| 22. | Lesens O, Deschenes M, Steben M, Belanger G, Tsoukas CM. Hepatitis C virus is related to progressive liver disease in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hemophiliacs and should be treated as an opportunistic infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1254-1258. |

| 23. | Yee TT, Griffioen A, Sabin CA, Dusheiko G, Lee CA. The natural history of HCV in a cohort of haemophilic patients infected between 1961 and 1985. Gut. 2000;47:845-851. |

| 24. | Di Martino V, Rufat P, Boyer N, Renard P, Degos F, Martinot-Peignoux M, Matheron S, Le Moing V, Vachon F, Degott C. The influence of human immunodeficiency virus coinfection on chronic hepatitis C in injection drug users: a long-term retrospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2001;34:1193-1199. |

| 25. | Ragni MV, Belle SH. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on progression to end-stage liver disease in individuals with hemophilia and hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1112-1115. |

| 26. | Goedert JJ. Prevalence of conditions associated with human immunodeficiency and hepatitis virus infections among persons with haemophilia, 2001-2003. Haemophilia. 2005;11:516-528. |

| 27. | Mohsen AH, Easterbrook PJ, Taylor C, Portmann B, Kulasegaram R, Murad S, Wiselka M, Norris S. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the progression of liver fibrosis in hepatitis C virus infected patients. Gut. 2003;52:1035-1040. |

| 28. | Fuster D, Planas R, Muga R, Ballesteros AL, Santos J, Tor J, Sirera G, Guardiola H, Salas A, Cabre E. Advanced liver fibrosis in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:1293-1297. |

| 29. | Rullier A, Trimoulet P, Neau D, Bernard PH, Foucher J, Lacoste D, Winnock M, Urbaniak R, Ballardini G, Balabaud C. Fibrosis is worse in HIV-HCV patients with low-level immunodepression referred for HCV treatment than in HCV-matched patients. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1088-1094. |

| 30. | Zhang YH, Chen XY, Wu H, Diao SQ. [A study of the progression of cirrhosis in patients with human immuno-deficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2005;13:264-266. |

| 31. | Monto A, Kakar S, Dove LM, Bostrom A, Miller EL, Wright TL. Contributions to hepatic fibrosis in HIV-HCV coinfected and HCV monoinfected patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1509-1515. |

| 32. | Nunes D, Fleming C, Offner G, O’Brien M, Tumilty S, Fix O, Heeren T, Koziel M, Graham C, Craven DE. HIV infection does not affect the performance of noninvasive markers of fibrosis for the diagnosis of hepatitis C virus-related liver disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:538-544. |

| 33. | Kramer JR, Giordano TP, Souchek J, Richardson P, Hwang LY, El-Serag HB. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:56-63. |

| 34. | Arnold DM, Julian JA, Walker IR. Mortality rates and causes of death among all HIV-positive individuals with hemophilia in Canada over 21 years of follow-up. Blood. 2006;108:460-464. |

| 35. | Pineda JA, Romero-Gomez M, Diaz-Garcia F, Giron-Gonzalez JA, Montero JL, Torre-Cisneros J, Andrade RJ, Gonzalez-Serrano M, Aguilar J, Aguilar-Guisado M. HIV coinfection shortens the survival of patients with hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:779-789. |

| 36. | Lumbreras B, Jarrin I, del Amo J, Perez-Hoyos S, Muga R, Garcia-de la Hera M, Ferreros I, Sanvisens A, Hurtado I, Hernandez-Aguado I. Impact of hepatitis C infection on long-term mortality of injecting drug users from 1990 to 2002: differences before and after HAART. AIDS. 2006;20:111-116. |

| 37. | Posthouwer D, Makris M, Yee TT, Fischer K, van Veen JJ, Griffioen A, van Erpecum KJ, Mauser-Bunschoten EP. Progression to end-stage liver disease in patients with inherited bleeding disorders and hepatitis C: an international, multicenter cohort study. Blood. 2007;109:3667-3671. |

| 38. | Valle Tovo C, Alves de Mattos A, Ribeiro de Souza A, Ferrari de Oliveira Rigo J, Lerias de Almeida PR, Galperim B, Riegel Santos B. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection in patients infected with the hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2007;27:40-46. |

| 39. | Brau N, Salvatore M, Rios-Bedoya CF, Fernandez-Carbia A, Paronetto F, Rodriguez-Orengo JF, Rodriguez-Torres M. Slower fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with successful HIV suppression using antiretroviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2006;44:47-55. |

| 40. | Smit C, van den Berg C, Geskus R, Berkhout B, Coutinho R, Prins M. Risk of hepatitis-related mortality increased among hepatitis C virus/HIV-coinfected drug users compared with drug users infected only with hepatitis C virus: a 20-year prospective study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:221-225. |

| 41. | Souza AR, Tovo CV, Mattos AA, Chaves S. There is no difference in hepatic fibrosis rates of patients infected with hepatitis C virus and those co-infected with HIV. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:223-228. |

| 42. | de Ledinghen V, Barreiro P, Foucher J, Labarga P, Castera L, Vispo ME, Bernard PH, Martin-Carbonero L, Neau D, Garcia-Gasco P. Liver fibrosis on account of chronic hepatitis C is more severe in HIV-positive than HIV-negative patients despite antiretroviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:427-433. |