Published online Mar 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1353

Revised: December 31, 2008

Accepted: January 7, 2009

Published online: March 21, 2009

AIM: To evaluate a new single-operator mini-endoscope, Spyglass®, for its performance, feasibility and safety in the management of pancreaticobiliary disease.

METHODS: In a multicenter retrospective analysis of patients undergoing intraductal endoscopy, we evaluated 128 patients (71 men, mean age 57.6 years). Indications were therapeutic (TX) in 72 (56%) and diagnostic (DX) in 56 (44%).

RESULTS: Peroral endoscopy was performed in 121 and percutaneous in seven. TX indications included CBD stones in 41, PD stones in six, and biliary strictures in 25. DX indications included abnormal LFT’s in 15, abnormal imaging in 38 and cholangiocarcinoma staging in three. Visualization of the stone(s) was considered good in 31, fair in six, and poor in four. Advancement of the electrohydraulic lithotripsy probe was not possible in three patients and proper targeting of the lesion was partial in four patients. A holmium laser was used successfully in three patients. Ductal clearance was achieved in 37 patients after one procedure and in four patients after two procedures. Diagnosis of biliary strictures was modified in 20/29 and confirmed to be malignant in 10/23. Of the modified patients, no diagnosis was available in 17. Spyglass® demonstrated malignancy in 8/17 and non-malignancy in nine. Suspected pathology by imaging studies and abnormal LFT’s was modified in 43/63 (66%). Staging of cholangiocarcinoma demonstrated multicentric cholangiocarcinoma in 2/3. There was no morbidity associated with the use of Spyglass®.

CONCLUSION: Spyglass Spyscope® is a first generation, single operator miniature endoscope that can evaluate and treat various biliary and pancreatic tract diseases.

- Citation: Fishman DS, Tarnasky PR, Patel SN, Raijman I. Management of pancreaticobiliary disease using a new intra-ductal endoscope: The Texas experience. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(11): 1353-1358

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i11/1353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1353

Intraductal endoscopy is an integral part of the evaluation and therapy of patients with biliary and pancreatic diseases. The use of cholangiopancreatoscopy was first described in the mid-1970s. The initial “baby” or “daughter” scopes were passed through the operating channel of the “mother” duodenoscope. These early endoscopes were not widely used due to cost, fragility, difficult maneuverability, limited optical resolution, and were easily damaged at the level of the duodenoscope elevator. In addition, these endoscopes required two trained endoscopists to operate. Due to these challenges, the field of intraductal endoscopy did advance for several years[12]. Newer miniature endoscopes offer improved steering ability, durability, better optics and smaller size. These endoscopes have been increasingly used for diagnostic and therapeutic applications[3–5]. Spyglass Spyscope® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), is a new single-operator endoscope that has been recently introduced into the endoscopic arena[6]. It includes the Spyscope® which is 10 Fr in diameter, has a 4-way tip deflection and has a 1.2 mm working channel. It houses the Spyglass® optical fiber, an independent accessory channel and a separate channel for water irrigation.

We evaluated the Spyglass Spyssope® for its performance, feasibility and safety.

In this multicenter (three tertiary institutions; Houston, Dallas and San Antonio, TX) retrospective analysis, we evaluated 128 patients (71 males, 57 women, mean age 57.6 years) with various pancreatobiliary disorders (Table 1). Of the procedures to which the patients had been subjected, 56 (44%) were diagnostic and 72 were therapeutic (56%). Diagnostic indications included abnormal serum liver tests in 15, abnormal imaging studies in 38, and staging of cholangiocarcinoma in three, Therapeutic indications included choledocholithiasis in 41, pancreatic stones in six and biliary strictures in 25. The majority of procedures were performed per-orally (121), with the remaining seven performed percutaneously. All procedures were performed under monitored anesthesia, had prophylactic intravenous antibiotics, and the majority were performed on an outpatient basis. Most patients had a previous endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and had a previous biliary sphincterotomy. All procedures were performed by an experienced biliary endoscopist.

| Patient characteristics | Cases (n) |

| Patients | 128 |

| Male:female | 71:57 |

| Peroral usage | 121 |

| Percutaneous usage | 7 |

| Diagnostic indications | 56 (44%) |

| Abnormal serum liver test | 15 |

| Abnormal imaging studies | 38 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma staging | 3 |

| Therapeutic indications | 72 (56%) |

| Choledocholithiasis | 41 |

| Pancreaticolithiasis | 6 |

| Biliary strictures | 25 |

Abnormal imaging studies included computed tomography, magnetic resonance and endoscopic ultrasound. Therapeutic intervention was performed with electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) and a holmium laser. Biopsies were obtained with the Spybite® as well as with standard biopsy forceps.

Spyglass Spyscope® procedure was performed by attaching the Spyglass Spyscope® to the duodenoscope, at the junction of the head and the shaft. The Spyscope® was introduced over a guide wire through the accessory channel. The Spyglass® was advanced through the Spyscope® just to its tip. The Spyglass Spyscope® apparatus was then advanced through the duodenoscope and then into either the bile duct or the pancreatic duct. The guide wire was then removed to facilitate Spyscope® tip deflection.

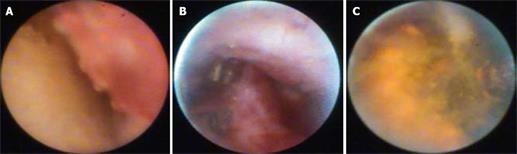

The main indication was determination of biological behavior of bile duct strictures (Table 2). The diagnosis of biliary strictures was modified in 20 of 29 patients. All 29 patients had a preoperative diagnosis of malignant bile duct stricture (three had established cholangiocarcinoma considered resectable in two, one stricture by MRCP, 25 strictures by ERC). Spyscope® endoscopy demonstrated malignancy (visualization, cytology and biopsy) in 11 of 20 patients. In three patients, Spyscope® endoscopy demonstrated stone related strictures (stones not seen by standard cholangiography), extrinsic compression of the distal bile duct in two, and scar-like tissue that appeared benign in four patients [all with Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)]. Visual components of malignancy included exophytic lesions, ulcerations, and raised lesions. Biopsy alone showed malignant features in 6/11 patients. Cytology showed malignant features in 4/20 patients. In patients with abnormal liver tests, abnormal Spyscope® endoscopy findings included stones in two, anastomotic ulceration in two, intrahepatic duct ulcer in one, intrahepatic adenoma in one, and normal in nine. Of patients with abnormal imaging studies, Spyscope® endoscopy demonstrated supra-papillary polypoid lesions in two, intraductal extension of ampullary cancer in one, stones in two, anastomotic surgical material in three, villous adenoma in three, cholangiocarcinoma in one, and normal in 26 (including no mucosal abnormalities in four patients with choledochal cyst type I) (Figure 1A and B). Of the patients with cholangiocarcinoma, two had resectable disease. Spyscope® endoscopy demonstrated intrahepatic disease in two and confirmed localized disease in one.

| Diagnostic Spyglass® indications | Cases (n) |

| Abnormal imaging and elevated liver panel | |

| Normal | 9 |

| Malignancy | 9 |

| Ductal ulcerations | 7 |

| Lithiasis | 7 |

| Extrinsic compression | 7 |

| Benign polypoid lesions | 4 |

| Total | 43 |

| Biliary strictures | |

| Diagnosis modified | 20/29 |

| Diagnosis confirmed malignant | 10/23 |

| Pre-operative diagnosis unknown | 17 |

| Post-operative diagnosis malignant | 9 |

| Post-operative diagnosis benign | 8 |

Spyglass Spyscope® endoscopy was used in 41 patients for biliary stone disease (Table 3). In 35 patients, it was used per-orally, and percutaneously in six patients due to surgically modified anatomy. Indications for biliary therapy included large choledocholithiasis (26), Mirizzi syndrome (1), intrahepatic lithiasis (10), and lithiasis associated with bile duct strictures (11). Some of these indications pertain to the same patient (i.e. large stone and Mirizzi syndrome). EHL was used in 38 patients and a holmium laser in three (Table 3). Lithotripsy was successful in 37/41 patients (Figure 1C). In five patients the EHL probe could not be advanced through the Spyscope® at the exit of the duodenoscope. In seven patients, the EHL probe could not be accommodated to fully target the stone. However, it produced enough fragmentation to remove the stone. Several factors were evaluated to assess feasibility, scope maneuverability, and technical success based on the ability to achieve ductal clearance of the Spyglass® system in the treatment of biliary disease. The initial assessment was based on the quality of visualization and related assessment of potential for intervention. Visualization (Table 3) was good in 31 (75.6%), fair in six (14.6%) and poor in four (12.9%). Maneuverability was superior if the guide wire was removed from the working channel. Percutaneous maneuverability was possible in 6/6 (100%) cases. The Spyscope® was advanced in the intrahepatics without difficulty in 8/10 (80%) patients. In 37/41 cases (87.1%) therapy for stones was completed by lithotripsy in one session (either by EHL or a holmium laser), and the remaining four patients required two sessions to achieve ductal clearance. A holmium laser was successfully used in three patients for stone destruction. Peroral use was easier than percutaneous. We noticed that the optical resolution of the Spyglass® deteriorated after ten uses. The best optical resolution was between uses one and seven.

| Spyglass® evaluation of choledocholithiasis | Cases (n) |

| Indications for choledochoscopy | |

| Large choledocholithiasis | 26 |

| Mirizzi syndrome | 1 |

| Intrahepatic lithiasis | 10 |

| Lithiasis with bile duct strictures (also with intrahepatic lithiasis) | 11 (7) |

| Maneuverability | |

| Intrahepatic peroral advancement without difficulty | 8/10 |

| Percutaneous advancement | 6/6 |

| Holmium laser usage | 3/3 |

| Poor targeting of lesion with EHL | 4/41 |

| EHL not advanced | 3/41 |

| Overall visualization | |

| Good | 31 |

| Fair | 6 |

| Poor | 4 |

Six patients had pancreatoscopy for stones related to chronic pancreatitis (Figure 2). All patients had a pancreatic sphincterotomy and a biliary sphincterotomy. All patients had a stricture distal to the stone and all the stones were localized to the head of the pancreas. The stone size varied between 5-14 mm. Two of the six stones were cast-like and impacted. In all patients, EHL was used via Spyglass Spyscope®. All patients underwent stricture dilatation before lithotripsy. Maneuvering the Spyglass Spyscope® in these patients was difficult due to its size (10 Fr). Stone clearance was successful in three of six patients, with the remainder treated with stent therapy.

Spyglass Spyscope® modified the preoperative diagnosis in 66% of the patients, prevented unnecessary surgery in two patients with cholangiocarcinoma, changed the diagnosis of malignant to benign disease in 45% of the patients with strictures, and provided successful therapy in 87% of the patients with stone disease. There was no morbidity or mortality associated with its use.

Since the introduction of intraductal endoscopy in the 1970s, several iterations have occurred to optimize the diagnosis and therapy for biliary and pancreatic disorders.

Reported uses include patient demographics (including young children and elderly) to diagnose and treat biliary and pancreatic stones or masses, strictures due to malignancy, primary sclerosing cholangitis and post-orthotopic liver transplantation.

The Spyglass® system is a single-operator three-channel, catheter based mini-endoscope. The system uses the Spyscope®, which has four-way maneuverability, accepts a 3.4-mm diameter catheter with a separate irrigation port, a channel for the 0.77 mm Spyglass® optical probe, and a 1.2-mm accessory channel. The accessory channel can be used to take biopsies with the Spybite and introduce EHL or holmium laser fibers.

Chen and Pleskow recently reported the initial experience with Spyglass Spyscope® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), a new single-operator endoscope. They evaluated 35 patients with the majority of cases (27) to evaluate indeterminate filling defects or strictures[6]. PSC was the most common preoperative diagnosis present in 9/35 patients and 9/35 patients had common bile duct stones diagnosed by a pre- or peri-procedure, with EHL performed in five cases. The new endoscope had a 91% success rate for achieving either diagnostic or therapeutic endpoints, with a diagnosis by visual inspection yielding a 100% sensitivity and 77% specificity. When biopsies were performed, the overall sensitivity was 71% and 100% specificity for determining the behavior of a lesion. A low complication rate of 6% was reported with cholangitis seen in two patients, one requiring abscess drainage.

Chen reported an initial model system with Spyglass® that demonstrated improved targeting of lesions with improved steering ability compared to standard choledochoscopes[7]. A follow-up evaluation with 35 patients described the first experience using the Spyglass® in patients with strictures, filling defects, choledocholithiasis, and gallbladder stent placements. Our experience with intraductal endoscopy using Spyglass® is one of the largest series to date and represents description of both diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. The use of Spyglass® resulted in management changes in two-thirds of patients and no complications occurred.

The primary indication for diagnostic intraductal endoscopy in the biliary tree is to evaluate strictures seen on abnormal imaging study or prior ERCP. The majority of these patients are either post-OLT or at risk for cholangiocarcinoma (i.e. patients with PSC or history of choledochal cyst). Several modalities such as methylene blue[8] and narrow band imaging[9] have been used to optimize diagnosis in patients with various bile duct disorders[6710–12], including liver transplant[5], PSC, and cholangiocarcinoma[1013–16]. Direct visualization and focused biopsy samples provide both endoscopic and pathological information to aid in diagnosis and treatment strategies. We described 29 patients who underwent Spyglass® to evaluate biliary strictures and the preoperative diagnosis was modified in 20 (68%) patients. All 29 patients had a preoperative diagnosis of malignant bile duct stricture, with 45% determined to be benign after Spyglass® evaluation. As with other intra-ductal endoscopes, bile duct stones were visualized in three Spyglass® cases, not seen on initial ERC.

Several reports detail the management of bile duct stones with standard choledochoscopy with EHL or laser therapies. Several authors have demonstrated the benefit of choledochoscopy in patients with filling defects or suspected choledocholithiasis by routine ERCP[517–20]. Siddiqui and colleagues reported 18 patients with suspected stones, with 14/18 treated with EHL and the remaining four patients had either benign epitheloid tumors, large-cell lymphoma and cholangiocarcinoma[5] Arya et al described their experience of EHL in 111 patients[17]. The authors’ primary use for choledochos-copy and EHL were stones larger than 2 cm, or those with associated stone-related strictures, with successful stone fragmentation in 89 of 93 patients (96%) and overall stone clearance in 85/94 patients (90%). Treatment failures were due to targeting problems and hard stones. In their experience, 76% received one EHL session, 14% with two sessions, and 10% with three or more sessions. Farrell et al used a modified single operator cholechodochoscope system for treatment of stones, with 39 % of stones larger than 2 cm and 35% with stones above a stricture[19]. More than half (54%) of patients in this cohort had multiple stones visualized and treated with choledochoscopy and EHL. They determined that the location of the stone, presence of multiple stones, presence of a stricture and the size of the stone were predictive factors for success and need for multiple EHL sessions.

Our series of 41 patients with bile duct stones using the Spyglass® system demonstrated similar results, with 87.1% of patients with clearance after one EHL session and the remaining patients with a second session. As with previous reports, difficulties in stone removal were related to passage of the EHL probe through the Spyscope® and targeting of the lesion with the EHL probe. We found that removal of the guide wire facilitated visualization and manipulation of the EHL probe.

Several authors have described experience with peroral pancreatoscopy to evaluate pancreatic lesions (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, strictures and treatment of stones)[21–25]. We demonstrated the use of Spyglass® in six patients with adequate visualization of pancreatic stones, all with strictures distal to the stone. Half of the patients were successfully treated with EHL-directed therapy, with the remaining patients treated with stent-directed therapy. The outer diameter of the Spyscope® catheter and visibility limited better access in the presence of strictures.

Choledochoscopy has been available to endoscopists for several years. It is of high value in the management of difficult biliary stones, biliary strictures, and determining the presence or absence of ductal disease. The same has been applied to pancreatoscopy, however only recently since the advent of small caliber mini-scopes. Spyglass® is a new intraductal scope that differs fundamentally from other existing miniscopes in its structure, its four-way steering ability, its separate irrigation channel, its ease of use and requirement for only one operator. Due to its different structure, the Spyscope® component is disposable and the Spyglass® optical probe is reusable. The innovative design and ease in use will create an increase in choledochoscopy by more endoscopists. The applications are likely to remain for therapy of difficult stone disease. However, its use will increase for staging of various biliary cancers as well as in the management of biliary tract disease in liver transplant patients. Likewise, the use of Spyglass® will increase in patients with various pancreatic disorders, but not at the same pace as biliary disease. Our findings in redefining two-thirds of patients with malignant disease may influence both biliary and pancreatic oncologic management.

Future studies are planned to evaluate therapeutic intervention with the Spyglass® and related intraductal endoscopes. Additionally, we anticipate further improvements in optical quality, smaller catheter size, and maneuverability. Advanced imaging modalities such as narrow band imaging and chromoendoscopy offer further improvement in diagnostic capabilities, which can be assessed in the treatment of patients with biliary and pancreatic disease. With an increase in use, of critical importance is the recognition of disease (both endoscopically and histologically) and terminology. Thus, we believe that there will be an increase in the literature reporting the use of Spyglass® in biliary and pancreatic disorders.

Intraductal endoscopy has been used for more than 30 years to evaluate and treat disorders of the biliary and pancreatic ducts. Cholangiopancreatoscopy allows direct visualization and permits focused biopsies and lithotripsy. Use was limited for several years due to cost, ease of breakage, difficult maneuverability, and limited optical resolution.

Spyglass Spyscope® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), is a new single-operator endoscope that can be used in the therapy of bilio-pancreatic disease. This intraductal endoscope is effective in the diagnosis of biliary strictures in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis, orthotopic liver transplantation and cholangiocarcinoma. The Spyscope® can also be used in the management of biliary and pancreatic stones. The research hotspot is the significant improvement in cholangiopancreatoscopy and the diversity of modalities that are demonstrated with the new endoscope.

The main advantages of the Spyglass Spyscope® are that it requires only one endoscopist, it has four-way steering ability, and a separate irrigation channel. This endoscope allows directed biopsies, can be used percutaneously, and permits the use of electrohydraulic lithotripsy or a holmium laser for the treatment of biliary and pancreatic stones.

This study demonstrates an effective new tool in the diagnosis and treatment of biliopancreatic disease using cholangiopancreatography.

Cholangiopancreatoscopy is the direct endoscopic evaluation of the bile or pancreatic ducts.

The authors present a preliminary report of a new endoscope to directly evaluate the biliary and pancreatic ducts. Their promising results assessed the performance, feasibility and safety of the new endoscope. The new intra-ductal endoscope was useful for discriminating benign biliary strictures from malignancy.

| 1. | Bar-Meir S, Rotmensch S. A comparison between peroral choledochoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:13-14. |

| 2. | Kozarek RA. Direct cholangioscopy and pancreatoscopy at time of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:55-57. |

| 3. | Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Moench C, Bittinger F, Otto G, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy unravels the endoscopic features of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1052-1058. |

| 4. | Bauer JJ, Salky BA, Gelernt IM, Kreel I. Experience with the flexible fiberoptic choledochoscope. Ann Surg. 1981;194:161-166. |

| 5. | Siddique I, Galati J, Ankoma-Sey V, Wood RP, Ozaki C, Monsour H, Raijman I. The role of choledochoscopy in the diagnosis and management of biliary tract diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:67-73. |

| 6. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. |

| 7. | Chen YK. Preclinical characterization of the Spyglass peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for direct access, visualization, and biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:303-311. |

| 8. | Caldwell SH, Oelsner DH, Bickston SJ, Mays K, Yeaton P. Intrahepatic biliary endoscopy in sclerosing cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:152-156. |

| 9. | Fukuda Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Tsuchiya S, Saisyo H. Diagnostic utility of peroral cholangioscopy for various bile-duct lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:374-382. |

| 10. | Gores GJ. Early detection and treatment of cholangiocar-cinoma. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:S30-S34. |

| 11. | Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Bittinger F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy in patients with biliary strictures: feasibility and outcome analysis. Endoscopy. 2008;40:563-571. |

| 12. | Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Moriyasu F, Gotoda T. Peroral cholangioscopic diagnosis of biliary-tract diseases by using narrow-band imaging (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:730-736. |

| 13. | Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Kim TK, Seo DW, Park JS, Hwang CY, Chang HS, Min YI. MR cholangiography versus cholangioscopy for evaluation of longitudinal extension of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:25-32. |

| 14. | Seo DW, Kim MH, Lee SK, Myung SJ, Kang GH, Ha HK, Suh DJ, Min YI. Usefulness of cholangioscopy in patients with focal stricture of the intrahepatic duct unrelated to intrahepatic stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:204-209. |

| 15. | Seo DW, Lee SK, Yoo KS, Kang GH, Kim MH, Suh DJ, Min YI. Cholangioscopic findings in bile duct tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:630-634. |

| 16. | Tischendorf JJ, Geier A, Trautwein C. Current diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:735-746. |

| 17. | Arya N, Nelles SE, Haber GB, Kim YI, Kortan PK. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy in 111 patients: a safe and effective therapy for difficult bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2330-2334. |

| 18. | Blind PJ, Lundmark M. Management of bile duct stones: lithotripsy by laser, electrohydraulic, and ultrasonic techniques. Report of a series and clinical review. Eur J Surg. 1998;164:403-409. |

| 19. | Farrell JJ, Bounds BC, Al-Shalabi S, Jacobson BC, Brugge WR, Schapiro RH, Kelsey PB. Single-operator duodenoscope-assisted cholangioscopy is an effective alternative in the management of choledocholithiasis not removed by conventional methods, including mechanical lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:542-547. |

| 20. | Hui CK, Lai KC, Ng M, Wong WM, Yuen MF, Lam SK, Lai CL, Wong BC. Retained common bile duct stones: a comparison between biliary stenting and complete clearance of stones by electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:289-296. |

| 21. | Howell DA, Dy RM, Hanson BL, Nezhad SF, Broaddus SB. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones using a 10F pancreatoscope and electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:829-833. |

| 22. | Kodama T, Tatsumi Y, Kozarek RA, Riemann JF. Direct pancreatoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:653-660. |

| 23. | Schoonbroodt D, Zipf A, Herrmann G, Wenisch H, Jung M. Pancreatoscopy and diagnosis of mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:479-482. |

| 24. | Yamaguchi T, Hara T, Tsuyuguchi T, Ishihara T, Tsuchiya S, Saitou M, Saisho H. Peroral pancreatoscopy in the diagnosis of mucin-producing tumors of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:67-73. |

| 25. | Yamao K, Ohashi K, Nakamura T, Suzuki T, Sawaki A, Hara K, Fukutomi A, Baba T, Okubo K, Tanaka K. Efficacy of peroral pancreatoscopy in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:205-209. |