Published online Apr 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2425

Revised: February 25, 2008

Published online: April 21, 2008

AIM: To investigate the role of the duodenum in the regulation of plasma ghrelin levels and body mass index (BMI), and the correlation between them after subtotal gastrectomy.

METHODS: Forty-two patients with T0-1N0-1M0 gastric cancer were divided into two groups after gastrectomy according to digestive reconstruction pattern, Billroth I group (n = 23) and Billroth II group (n = 19). Ghrelin levels were determined with radioimmunoassay (RIA) before and on d 1, 7, 30 and 360 after gastrectomy, and BMI was also measured.

RESULTS: The two groups had identical postoperative trends in ghrelin alterations during the early stage, both decreasing sharply to a nadir on d 1 (36.7% vs 35.7%), then markedly increasing on d 7 (51.0% vs 51.1%). On d 30, ghrelin levels in the Billroth I group were slightly higher than those in the Billroth II group. However, those of the Billroth I group recovered to 93.6% on d 360, which approached, although lower than, the preoperative levels, and no statistically significant difference was observed. Those of the Billroth II group recovered to only 81.6% and manifested significant discrepancy with preoperative levels (P = 0.033). Compared with preoperative levels, ghrelin levels of the two groups decreased by 6.9% and 18.4% and BMI fell by 3.3% and 6.4%, respectively. The linear regression correlations were revealed in both groups between decrease of ghrelin level and BMI (R12 = 0.297, P = 0.007; R22 = 0.559, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Anatomically and physiologically, the duodenum compensatively promotes ghrelin recovery and accordingly enhances BMI after gastrectomy. Regarding patients with insufficient ghrelin secretion, ghrelin is positively associated with BMI.

- Citation: Wang HT, Lu QC, Wang Q, Wang RC, Zhang Y, Chen HL, Zhao H, Qian HX. Role of the duodenum in regulation of plasma ghrelin levels and body mass index after subtotal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(15): 2425-2429

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i15/2425.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2425

Ghrelin, a recognized brain-gut peptide with 28 amino acids, was recently discovered as the intrinsic ligand of the secretagogue receptor[1], which exerts considerable vital physiological activities within the body, beyond stimulating growth hormone release. The duodenum is the major source of ghrelin secretion apart from the stomach, which is responsible for most of ghrelin production in the body[2], while the bowel and some organs secrete less through paracrine or autocrine mechanisms, which accounts for the partially compensatory secretion after gastrectomy[3–8]. Known as a unique orexigenic hormone, ghrelin contributes to maintaining the body's energy balance by communicating signals of energy stores to the brain, then inducing appetite, promoting food intake, and reducing energy expenditure[5–9].

Gastrectomy is the predominant therapy for most stomach-associated diseases, including tumors and complex ulcers. However, weight loss is a ubiquitous sequela for which no satisfactory explanations have been given, although various measures have been employed to treat it, including drugs, diet therapy, and even secondary surgery. Regarding the gastroduodenum as the main source of ghrelin, which has a considerable influence on energy balance, a lot of research has focused on the correlation between ghrelin and energy balance. However, to date, there have been no studies on the role of the duodenum in regulating ghrelin plasma levels and body mass index (BMI) after gastrectomy. It is thought that the digestive endocrine and exocrine functions will be impaired if the duodenum is devoid of long-term contact with gastric contents[810–12]. Accordingly, we hypothesize that a similar situation would exert the same influence on ghrelin levels.

Patients with T0-1N0-1M0 (AJCC, American joint committee on cancer, 2003) stage gastric cancer were enrolled in our study from September 2004 to July 2006. Their clinical characteristics were collected, comprising gender, age, height, weight and BMI. Patients with coincidental endocrine diseases such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid or pituitary disease were excluded, as were those with BMI beyond the range of 18-26 kg/m2. Curative subtotal gastrectomy, defined as resection of no less than two-thirds of the distal stomach, with standard D2 lymph node resection, was performed on each patient by the same team. Those who contracted severe complications, such as anastomosis leakage, intra-abdominal infection, or ileus, and those who displayed tumor recurrence or metastasis by endoscopy, abdominal computer tomography (CT), sonography, or tumor biomarkers during regular follow-up, were also excluded. The subjects were divided into two groups according to their reconstruction patterns of digestive continuity, gastroduodenal anastomosis, i.e., Billroth I anastomosis (n = 23); and gastrojejunal anastomosis, with an end-to-side anastomosis of the jejunum, i.e., Billroth II anastomosis (n = 19).

As concerns the impact of the operation itself on ghrelin levels, during the same period, we chose 20 colorectal cancer patients who underwent surgery in our department as a control group, with the same screening conditions as the study group. All patients gave their informed consent before the study. Blood samples (10 mL each) were collected at 8:00 a.m. preprandially before and on d 1, 7, 30 (1 mo) and 360 (1 year) after operation. All patients fasted from midnight before blood collection. Plasma ghrelin and leptin levels of each sample were analyzed. In addition, with regard to the impact of cancer on both hormones, subjects were contrasted with 20 healthy individuals whose blood samples were drawn during regular physical examinations.

All blood samples were drawn into tubes containing EDTA and aprotinin. Plasma was obtained and stored at -70°C until assayed. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min. Total plasma ghrelin was measured with a commercially available RIA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA, USA) using 125I-labelled ghrelin tracer and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against full-length octanoylated human ghrelin that measures total circulating ghrelin. Plasma leptin was measured with a human RIA kit (Linco Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO, USA) using 125I-labelled leptin tracer. Both hormones were measured in duplicate and the mean was determined.

All results were expressed as mean ± SD. ANOVA with Student-Neuman-Keul post hoc test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in ghrelin, leptin levels and BMI between the two groups before operation, and ghrelin or leptin levels of the same group between different time points after operation. Differences of ghrelin levels between the two study groups at the same time after operation were analyzed with the unpaired t test. Both decrease and increase of ghrelin, leptin levels and BMI were expressed as a percentage of the preoperative levels. The relationship between them was displayed with linear regression. The coefficient of correlation R2 was used as the gauge of their relationship. A one-tailed test was adopted in each analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

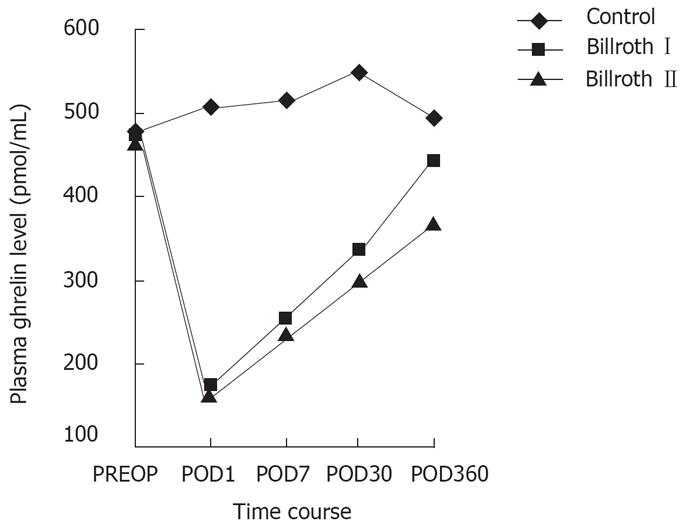

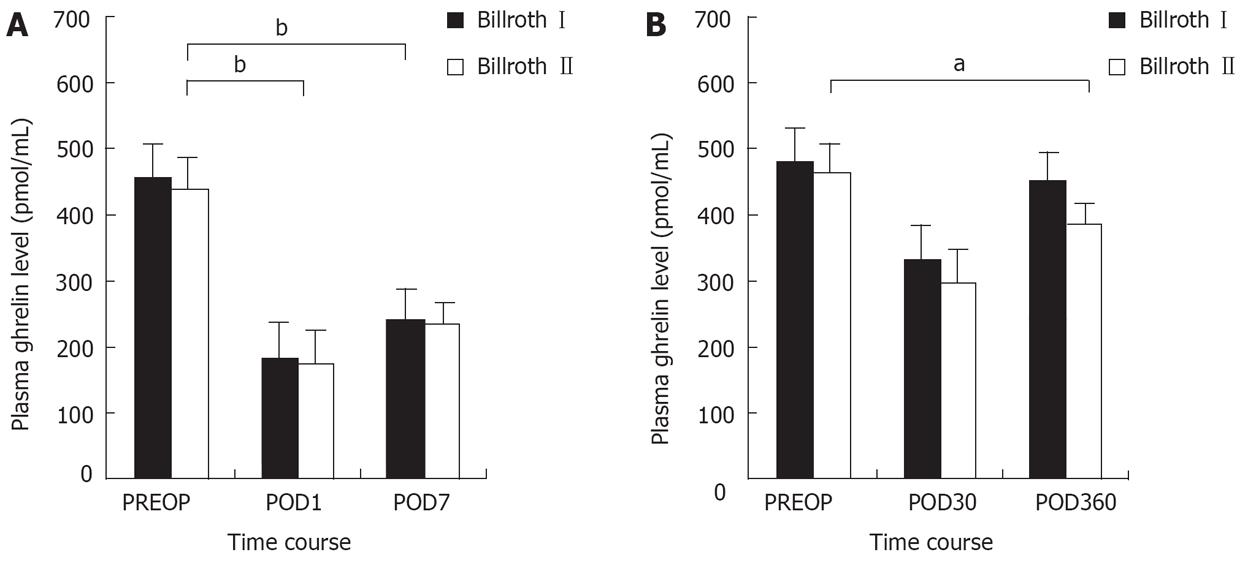

There was no significant difference in preoperative chara-teristics, including ghrelin, leptin levels and BMI between the groups (Table 1). As for the control group, ghrelin levels increased slightly at first, then gradually decreased to preoperative levels during 360 d after operation (Figure 1). Leptin levels of all groups were less affected and no difference existed between the groups at the same time. The two groups had identical trends in ghrelin levels during the early stage after the operation, decreasing sharply to a nadir on d 1 (36.7% vs 35.7%). The levels then increased markedly on d 7 (51.0% vs 51.1%), and showed no difference between the two groups at the same time (169.35 ± 45.9 pg/mL vs 163.7 ± 49.3 pg/mL; 235.4 ± 61.3 pg/mL vs 232.1 ± 67.0 pg/mL). Nevertheless, the ghrelin levels of the Billroth I group recovered more obviously during the later stage compared with the Billroth II group (Figure 2). On d 30, ghrelin levels in the two groups increased to 70.6% (330.2 ± 77.1 pg/mL) and 67.2% (300.3 ± 80.1 pg/mL) respectively, with those of the Billroth I group higher than those of the Billroth II group, whereas no significant difference existed between the two. On d 360, ghrelin levels of the Billroth I group recovered to 93.1% (435.9 ± 110.2 pg/mL), although they were lower than preoperative levels, but no significant difference was revealed. However, ghrelin levels in the Billroth II group recovered to only 81.6% (369.7 ± 90.1 pg/mL), evidently lower than preoperative levels (P = 0.033). On d 360, ghrelin levels in the Billroth I group were distinctly higher than those in the Billroth II group (P = 0.035). From d 7 through to d 360, ghrelin levels in the two groups increased by 42.1% and 30.6%, respectively, with a significant difference between the levels (P = 0.003).

| Group | Healthy | Control | Billroth I | Billroth II |

| Object number | 20 | 20 | 23 | 19 |

| Gender (male:female) | 8:12 | 13:7 | 11:12 | 8:11 |

| Age (yr) | 40.4 ± 10.2 | 42.2 ± 7.4 | 50.7 ± 5.5 | 48.0 ± 6.4 |

| BMI | 22.2 ± 2.2 | 22.7 ± 2.2 | 21.9 ± 2.8 | 2 1.7 ± 2.7 |

| Ghrelin (pg/mL) | 460 ± 117.8 | 472 ± 115.9 | 468.0 ± 126.9 | 460.5 ± 129.4 |

| Leptin (ng/mol) | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.7 |

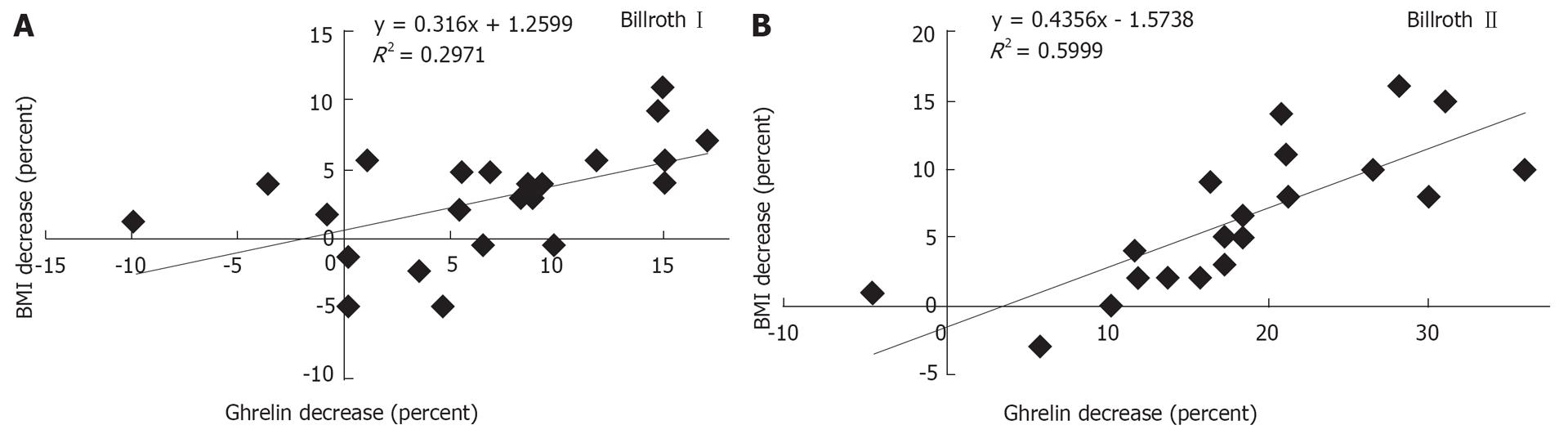

Compared with preoperative levels, ghrelin levels in the Billroth I and Billroth II groups decreased by 6.9% and 18.4%, respectively, on d 360, which showed a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.035), while BMI decreased by 3.3% and 6.4%, respectively, which also showed a significant difference (P = 0.035). The linear regression correlations were manifested between decrease of ghrelin level and BMI in both groups (R12 = 0.297, P = 0.007; R22 = 0.559, P < 0.001). Neither the correlation nor the regression coefficient of the Billroth II group was higher than that of the Billroth I group (Figure 3).

Ghrelin has recently been implicated in the development of malignant tumors[13], whereas these tumors did not show any effect on plasma ghrelin levels in our study. Postoperative ghrelin levels in colorectal cancer patients increased and then recovered gradually to normal, while those in gastric cancer patients decreased abruptly in the early stage, then rose gradually, although remaining lower, one year later compared with the preoperative level. We can generalize from the above that a postoperative decrease in ghrelin was induced by gastrectomy, but not the surgery itself or by trauma, or anesthesia or any factors involved in anesthesia.

As far as gastrectomy was concerned, a major portion of the stomach was removed, including part of the fundus, a major source of ghrelin production. This accounted for a sharp postoperative decrease in ghrelin levels, whereas due to compensatory secretion of the remaining part of the stomach, the duodenum, and other organs involved, ghrelin levels increased gradually.

Intriguingly, in the early phase after the operation, the two groups manifested identical profiles of ghrelin levels, whereas in the late phase, the ghrelin levels in the Billroth I group increased more distinctly than those in the Billroth II group, although neither approached preoperative levels. We consider that the cause of this was the discrepant restoration patterns of digestive continuity. This reveals that the duodenum is the most crucial ghrelin-producing organ, except for the stomach. The duodenum compensatively secretes ghrelin more effectively in an anatomical-physiological continuity, as in a Billroth I anastomosis, as compared to that in the relatively isolated Billroth II anastomosis.

This implies that long-term absence of contact with gastric contents exerts a predominant effect on the duodenum in postoperative ghrelin secretion. It is considered by some researchers that gastroduodenal exposure to food is not essential to ghrelin secretion, in that most X/A-like cells are closed, which means that they have an impact upon the basolateral membrane adjacent to the bloodstream, but do not open towards the digestive lumen[214]. However, merely by virtue of this, it cannot be denied that there is probably a trigger for the production of ghrelin related to food contact by some other unknown means. Furthermore, X/A-like cells in the duodenum and intestine gradually open concurrently towards the lumen and the microvascular circulation.

Compatible with our point, Qader et al have demonstrated ghrelin concentrations in plasma and gastroduodenal mucosa in rats given short-term total parental nutrition were reduced by 50% simultaneously[15]. Long-term lack of food contact would reduce the duodenum to atrophy and hypoplasia, and even disturb endocrine functions, which if severe, would lead to pathophysiological disorders[1617]. Thus, anatomical-physiological normalcy is essential for the duodenum to exert its customary ghrelin-producing activity after gastrectomy.

It has been revealed that ghrelin levels decrease as biliopancreatic limbs lengthen in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for obesity[18], which is in accordance with our view that the opportunity for interactive contact between the duodenum and gastric contents decreases as biliopancreatic limbs lengthen. Cummings et al have demonstrated downregulation or reduction of ghrelin levels may be a result of "overridden inhibition" of gastroduodenal ghrelin-producing cells isolated from contact with enteral nutrients. This resembles the paradoxical suppression of growth hormone by continuous signaling from gonadotropin-releasing hormone or growth hormone-releasing hormone[1920]. However, it lacks convincing proof and further investigation is required to decipher how the duodenum regulates ghrelin production and levels after gastrectomy with different digestive continuity reconstructions.

Considerable evidence supports the view that ghrelin levels correlate inversely with BMI and manifest compensatory changes in response to body weight alterations[20–25]. Several clinical studies have demonstrated long-term administration of ghrelin promotes weight gain in patients with cachexia due to chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or even malignant tumors, by stimulating food intake, decreasing energy expenditure and regulating other aspects of energy homeostasis[212526].

As regards patients with insufficient ghrelin secretion after gastrectomy, we found it interesting that a decrease in ghrelin level was positively correlated with a decrease in BMI. This means that the ghrelin level is positively associated with BMI in individual patients, which implies that postoperative weight loss results from down-regulation of ghrelin levels after gastrectomy, and may be treated with administration of exogenous ghrelin. With regard to linear regression correlation between ghrelin levels and BMI, the Billroth II group presented a higher correlation or regression coefficient compared with the Billroth I group, which implies that the efficacy of ghrelin for the regulation of BMI is associated to some extent with its concentration.

In summary, anatomical-physiological duodenal normalcy promotes ghrelin recovery through compensatory secretion, thereby leading to BMI recovery, while an isolated duodenum displays obviously insufficient ghrelin secretion, which results in a decrease in BMI. Regarding the individual patient with insufficient ghrelin secretion after gastrectomy, ghrelin levels correlate positively with BMI.

It has been revealed that ghrelin contributes to weight gain and maintaining energy balance within the body, and weight loss is a ubiquitous sequela after subtotal gastrectomy. It is unclear whether anatomical-physiological duodenal normalcy promotes ghrelin recovery through compensatory secretion and weight gain after gastrectomy.

The aim of this study was to analyze whether the duodenum plays a role in regulation of plasma ghrelin levels and body mass index (BMI) after subtotal gastrectomy.

This was a prospective clinical study that focused on the duodenum in different digestive reconstruction models, which contributed differently to ghrelin secretion and weight gain.

This study provides surgeons with evidence to apply digestive reconstruction that has an anatomical-physiological duodenal normalcy during operation, and it also reveals that exogenous ghrelin may be useful in therapy of severe weight loss due to gastrectomy.

Ghrelin, a brain-gut peptide, was recently discovered as the intrinsic ligand of the secretagogue receptor. BMI (kg/m2) is widely used as a gauge to measure fat storage within the body.

This was a study of the long-term effect of exclusion of the duodenum on the production of ghrelin, and presents original information about the role of the duodenum. It is very interesting.

| 1. | Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656-660. |

| 2. | Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, Sawaguchi A, Mondal MS, Suganuma T, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4255-4261. |

| 3. | Van der Lely AJ, Tschop M, Heiman ML, Ghigo E. Biological, physiological, pathophysiological, and pharmacological aspects of ghrelin. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:426-457. |

| 4. | Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K. Biological, physiological, and pharmacological aspects of ghrelin. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:398-410. |

| 5. | Kojima M, Kangawa K. Drug insight: The functions of ghrelin and its potential as a multitherapeutic hormone. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:80-88. |

| 6. | Davenport AP, Bonner TI, Foord SM, Harmar AJ, Neubig RR, Pin JP, Spedding M, Kojima M, Kangawa K. International Union of Pharmacology. LVI. Ghrelin receptor nomenclature, distribution, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:541-546. |

| 7. | Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin: structure and function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:495-522. |

| 8. | Tritos NA, Kokkotou EG. The physiology and potential clinical applications of ghrelin, a novel peptide hormone. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:653-660. |

| 9. | Cummings DE. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:71-84. |

| 10. | Raybould HE. Visceral perception: sensory transduction in visceral afferents and nutrients. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i11-i14. |

| 11. | Buchan AM. Nutrient Tasting and Signaling Mechanisms in the Gut III. Endocrine cell recognition of luminal nutrients. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1103-G1107. |

| 13. | D’Onghia V, Leoncini R, Carli R, Santoro A, Giglioni S, Sorbellini F, Marzocca G, Bernini A, Campagna S, Marinello E. Circulating gastrin and ghrelin levels in patients with colorectal cancer: correlation with tumour stage, Helicobacter pylori infection and BMI. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:137-141. |

| 14. | Sakata I, Nakamura K, Yamazaki M, Matsubara M, Hayashi Y, Kangawa K, Sakai T. Ghrelin-producing cells exist as two types of cells, closed- and opened-type cells, in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Peptides. 2002;23:531-536. |

| 15. | Qader SS, Salehi A, Hakanson R, Lundquist I, Ekelund M. Long-term infusion of nutrients (total parenteral nutrition) suppresses circulating ghrelin in food-deprived rats. Regul Pept. 2005;131:82-88. |

| 16. | Solomon TE. Trophic effects of pentagastrin on gastrointestinal tract in fed and fasted rats. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:108-116. |

| 17. | Saudler F, Hakansor R. Peptide hormone-producing endocrine/paracrine cells in the gastro-entereatic region. The peripheral nervous system. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Amsterdam: Elsevier 1998; 219-295. |

| 18. | Cummings DE, Shannon MH. Ghrelin and gastric bypass: is there a hormonal contribution to surgical weight loss? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2999-3002. |

| 19. | Cummings DE, Shannon MH. Roles for ghrelin in the regulation of appetite and body weight. Arch Surg. 2003;138:389-396. |

| 20. | Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP, Purnell JQ. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623-1630. |

| 21. | Nagaya N, Kangawa K. Ghrelin in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Nippon Rinsho. 2004;62 Suppl 9:430-434. |

| 22. | Leidy HJ, Gardner JK, Frye BR, Snook ML, Schuchert MK, Richard EL, Williams NI. Circulating ghrelin is sensitive to changes in body weight during a diet and exercise program in normal-weight young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2659-2664. |

| 23. | Popovic V, Svetel M, Djurovic M, Petrovic S, Doknic M, Pekic S, Miljic D, Milic N, Glodic J, Dieguez C. Circulating and cerebrospinal fluid ghrelin and leptin: potential role in altered body weight in Huntington's disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:451-455. |

| 24. | Garcia JM, Garcia-Touza M, Hijazi RA, Taffet G, Epner D, Mann D, Smith RG, Cunningham GR, Marcelli M. Active ghrelin levels and active to total ghrelin ratio in cancer-induced cachexia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2920-2926. |

| 25. | Nagaya N, Itoh T, Murakami S, Oya H, Uematsu M, Miyatake K, Kangawa K. Treatment of cachexia with ghrelin in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:1187-1193. |

| 26. | Neary NM, Small CJ, Wren AM, Lee JL, Druce MR, Palmieri C, Frost GS, Ghatei MA, Coombes RC, Bloom SR. Ghrelin increases energy intake in cancer patients with impaired appetite: acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2832-2836. |