Published online Aug 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i32.4385

Revised: January 15, 2007

Accepted: January 25, 2007

Published online: August 28, 2007

AIM: To retrospectively investigate the effect and safety of various new type precut sphincterotomy techniques (VNTPST) in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreato-graphy (ERCP) due to difficult biliary duct cannulation (DBC).

METHODS: A plough-like pull-type sphincterotome (PLPTS) or improved short nose sphincterotome or improved needle knife was applied. VNTPST was carried out in 30 of 280 patients, whose biliary tract could not be exposed well or deep cannulation was difficult to perform during ERCP with traditional methods. Patients were followed up for short-term complications and the therapeutic effect of VNTPS was observed and compared with that of traditional endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST).

RESULTS: A total 280 patients underwent ERCP, of which 3 failed in operation because of pathological features in stomch or duodenum, 247 successfully underwent traditional ERCP (89.1%, 247/277), 30 failed (10.8%, 30/277). VNTPS technique succeeded in 24 (80%, 24/30) of 30 cases. The successful rate of deep biliary duct cannulation increased 8.6% (24/277), the total cannulation successful rate following precut was 97.7%. There was a significant difference between the two groups (97.7% vs 89.1%, χ2 = 17.1, P < 0.01). The incidence of complications was 9.3% (26/277) for traditional ERCP group and 13.3% (4/30) for VNTPS technique group. Guideline tip was broken in pancreatic duct (KPDGP) of one patient, and there was no pancreatitis, slight or moderate bleeding postoperatively occurred in 2 patients, 1 patient had bleeding during operation (PDWN). There were no differences between VNTPS technique group and traditional ERCP (TRERCP) group (13.3% vs 9.3%, χ2 = 0.478, P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: VNTPS procedure and Deng’s precut are highly effective methods to get biliary access during ERCP with DBC. With skillful techniques, it can increase the successful rate for deep cannulation of biliary duct and decrease complications. VNTPS technique, especially Deng’s precut is as effective and safe as EST. This technique can be well performed in hospitals without particular equipments.

- Citation: Deng DH, Zuo HM, Wang JF, Gu ZE, Chen H, Luo Y, Chen M, Huang WN, Wang L, Lu W. New precut sphincterotomy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in difficult biliary duct cannulation. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(32): 4385-4390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i32/4385.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i32.4385

McCune reported ERCP in 1968 for the first time[1]. In China, ERCP was imported by Peking Union Hospital in 1974. Dr. Ming-Zhang Chen initially reported endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), but it has a lower successful rate. With the advances in surgical techniques and equipments, the successful rate for ERCP was 96.1% in 1990s in China[2], which is similar to the international reports[3,4]. Due to various factors, catheter cannot always be inserted into the bile duct successfully, leading to failure in TERCP.

Precut was initially reported by Siegel[5], the successful rate for ERCP can go up with the success of precut. It was reported that the successful rate for precut is 77%-91%[6,7]. The application of precut is limitted[8-11] because more complications occur, few reports on its use are available.

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data obtained from 280 cases and evaluated the effect and safety of VNTPST in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (DTERCP) with DBC.

Two hundred and eighty patients underwent ERCP in our hospital from April 2004 to September 2006, of them 247 succeeded in TRERCP, 30 (13 males, 17 females, aged 26-88 years, with a mean age of 66 years) failed, and 24 succeeded in percut technique. Among the 30 cases, 7 were diagnosed as Oddi’s sphincer stenosis (OSS) combined with choledocholithiasis, 2 as inlayed choledocholithiasis, 8 as simple constrictive papillitis (one as combined juxtapapillary diverticula), 3 as pancreatic head carcinoma, 2 as duodenal papilla carcinoma, 1 as papillary adenomatoid hyperplasia, 3 as ampullary carcinoma and distal bile duct cancer (DBDC), 2 as common bile duct inflammatory strictures, 2 as upper and middle bile duct carcinoma combined with inflammatory papilla stenosis. GF240 electric duodenal endoscope and PLPTS were from Olympus Company. Modified short nose sphincterotome or needle knife was a plough-like pull-type sphincterotome (PLPTS). An Olympus’s high-frequency electrosurgical unit and several kinds of guide wire were used in all procedures.

Preoperative preparation was the same as the standard ERCP. Patients underwent standard ERCP at first, followed by VNTPST when deep cannulation was difficult.

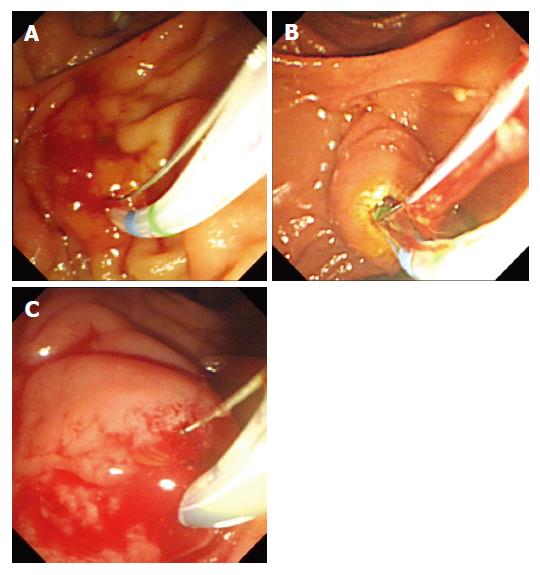

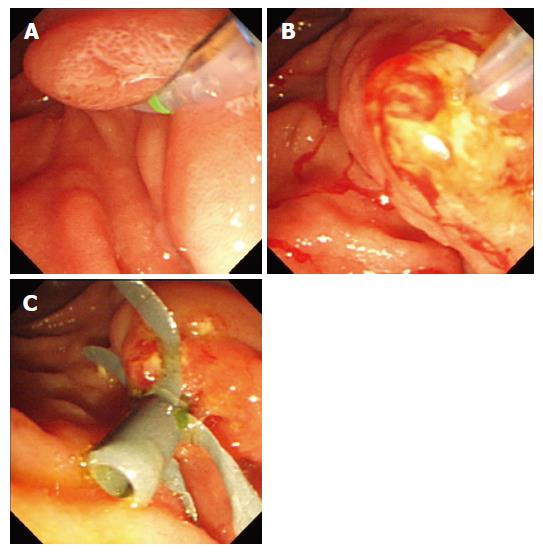

Modified pancreatic sphincter precutting (MPSP): Before precut, the exact direction of incision was determined and some movements were made in the correct direction as previously described (Figure 1 A-C)[12]. Incision was made in 10-12 o’clock point from the papillary orifice. The pure precut currently used was set at index 3.5-4.5, precut was performed by exerting pressure with the wire at the roof of PLPTS. The spin and PLPTS were lifted and the precut length was about 0.5-0.8 cm. The incision was extended in the submucosa until biliary effusion was detected. The precut was successful when catheter or guide wire was inserted into the common bile duct (CBD). General EST was performed with guide wire. A needle-knife precut was used if biliary cannulation failed. MPSP was more effective for type “Y” pancreaticobiliary ductal junction or type “V” without papillary stenosis. The pancreatic sphincter could be inserted with the help of guide wire or scalpel. PSP was not available for type “II”. No bleeding and perforation occurred. MPSP was safe and less dangerous, but complications such as pancreatitis occurred. Electrical coagulation and blending current should be limited

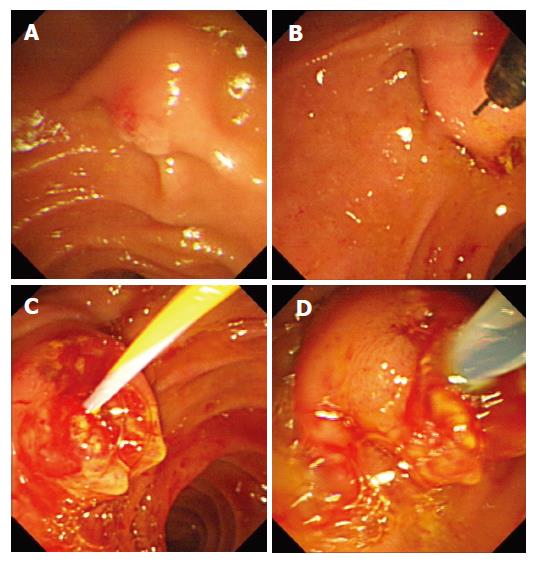

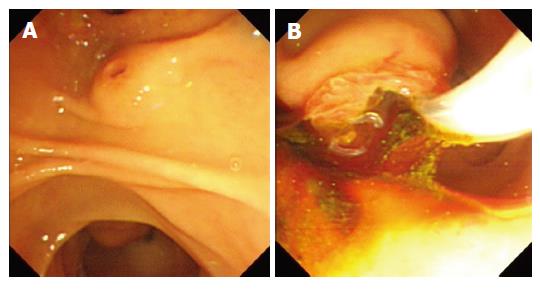

Precut down with needle (PDWN): When biliary cannulation was unsuccessful due to papillary stenosis, ampullary edema or abnormal ampullary anatomy (Figure 2 A-D). PDWN improved by PLPTS should be applied. To expose the needle (3-5 mm in length), the power source was set at index 3.5-4.5 with the exact direction adjusted. Incision was made in the 11 o’clock direction to the papillary orifice. The electric current index depended on the ampullary size and the edema degree. The incision was extended in layers from the papilla duodenal mucosa to the bile duct sphincter or bile seepage, then a catheter assisted with ultra-slipping guide wire was inserted into the bile duct. PDWN was performed repeatedly if biliary cannulation failed. When the bile duct sphincter was exposed or the incision was very deep, and the bile duct orifice could not be found or a catheter could not be inserted, it suggested that the anatomy of common bile duct was abnormal and precut should be stopped. Otherwise biliary duct or duodenum perforation might occur. Since perforation would occur after EST due to moving up of the incision orifice after precut, EST should not be very long.

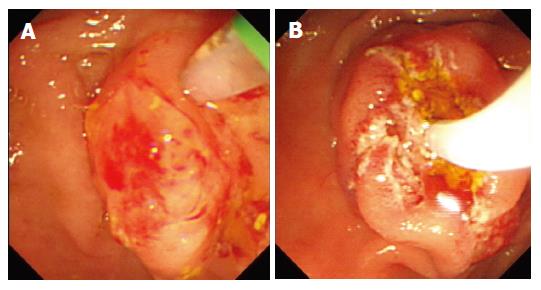

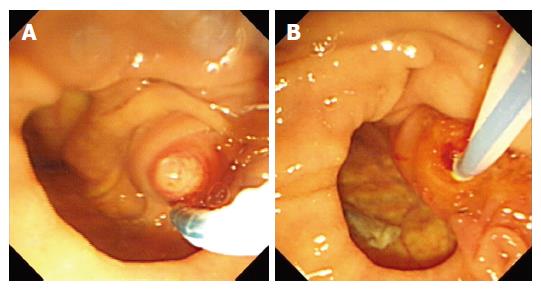

Precut up with needle (PUWN): PUWN was suitable for the mini papilla with a small orifice (Figure 3 A-B). The pure cutting current was used in the course, with the papilla adjusted to the left side of the visual field, the wire (3 mm) exposed, the needle anchored at the orifice. The bridge or elevator rotating the endoscope in the direction of anticlockwise was lifted while the current was applied for incision. PUWN was performed. The following step was the same as PDWN. This kind of precut might cause pancreatitis and the depth of incision was variable and uncontrolled. PUWN was not performed when the pailla orifice was not detectable.

Short nose knife precut (SNKP): SNKP could be performed when papilla orifice was variable. A short nose knife was inserted into the orifice in 11 o’clock direction with pure cutting current until a seepage of bile was detected, then a standard catheter was inserted into CBD. The depth of incision by SNKP was easy to control, not resulting in perforation, but it was not so convenient in comparison with a needle knife for duodenal ampulla calculus incarceration.

Pancreatic duct guideline precut (PDGP): A short nose knife or needle-knife was inserted into the papilla orifice while keeping the pancreatic duct guideline. The direction and depth could be controlled by pancreatic duct guide wire, which was not convenient for the small aperture endoscope.

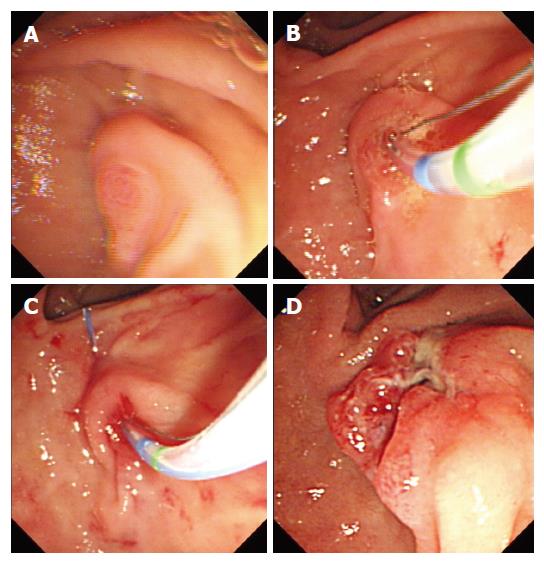

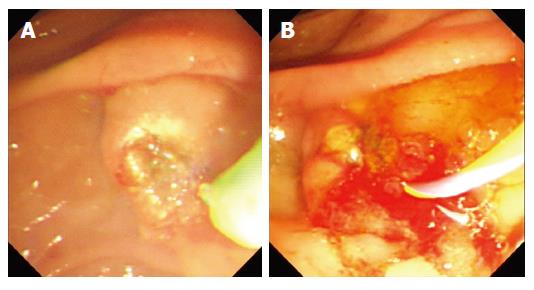

Mucosal bridge precut (Deng’s precut): When PLPTS was inserted into the bile duct with difficulty, the assistant strained the knife tightly to bend the sphincterotome, with the knife action adjusted in line with bile duct axis, and inserted the PLPTS tip from the papillary orifice, the hard guideline piercing through the ampullary duodenal mucosa, cut the ampullary duodenum side mucosal bridge until a seepage of bile was detectable, then inserted the guideline or the catheter into the duct (Figure 4 A-D). The performance could be followed by NKF if the attempt failed. This method could also be applied in patients with inflammatory papilla stenosis or combined upward papillary diverticula.

Up-removal orifice technique (UROT): This technique was applied when bile duct cannulation could not be achieved for the papilla orifice or bending endoscope could not be lifted up to the orifice (Figure 5 A-C). The assistant strained PLPTS tightly and tried to access the orifice with PLPTS tip, then raised the papilla mucosa and cut it for removing the orifice. When the bile duct axis was exposed after UROT, normal standard cannulation was easily performed.

Bending or rotating endoscope technique(BERET): When the papilla could not be lifted due to pathological changes or postoperative adhesions in the duodenum, which may result in standard cannulation failure, deep cannulation could be achieved by bending or rotating endoscope (Figure 6 A and B).

Pancreatic duct guideline cannulation (PDGC): When the knife was inserted into the pancreatic duct repeatedly, the guide wire might be kept in the pancreatic duct, then the knife or catheter must be inserted into bile duct through the endoscopic biopsy duct (Figure 7 A and B).

Comprehensive technology (CT): When incision could not be made by one single method, other precut procedures such as NKF, could be performed in combination until cannulation was achieved (Figure 8 A and B).

Data were expressed as percent and processed with chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 280 consecutive patients underwent ERCP with a standard catheter, of them, 3 gave up the operation because of pathological changes in stomach or in duodenum, 247 succeeded (89.1%, 247/277), 30 failed (10.8%, 30/277). Twenty-four of the 30 cases (80%, 24/30) succeeded in VNTPS technique. The successful rate for deep duct bile cannulation was increased 8.6% (24/277), the total successful cannulation rate following precut reached 97.7% (271/277). There was a significant difference between them (97.7% vs 89.1%, χ2 = 17.1, P < 0.01).

Among the successful cases, 2 succeeded in MPSP, 3 in PDWN, 2 in PUWN, 1 in SNKP, 2 in PDGP, 2 in Deng’s precut (one was inflammatory papilla combined with upward papilla diverticula), 3 in UROT, 2 in BERET, 1 in KPDGC. Comprehensive technology achieved success in 6 cases and failed in 6 cases. Among the unsuccessful cases, 1 was diagnosed as OSS combined with cholelocholithiasis, 1 as pancreatic head carcinoma, 2 as duodenal papilla carcinoma, 1 as distal bile carcinoma, 1 as lower segmental stenosis of common bile duct (over 1.5 cm in length).

The incidence of complications in traditional ERCP was 9.3% (26/277). The final diagnoses included suppurative cholangitis in 2 cases (1 was cured with conservative treatment, 1 underwent surgical therapy), acute severe pancreatitis in 2 cases, mild acute pancreatitis in 8 cases, bleeding during sphincterotomy in 4 cases, massive hemorrhage in gastrointestinal tract in 1 case, moderate bleeding after phincterotomy in 2 cases, transient abdominal pain and jaundice in 2 cases, cholangitis in 2 cases, transient cerebropathia in 2 cases, fever in 1 case. Mortality was not related to the endoscope.

The complication rate in VNTPS technique group was 13.3% (4/30). The tip of the soft wire was broken in the pancreatic duct of 1 case. Pancreatitis was not found in PDGP. Mild to moderate bleeding occurred in 2 cases and cured after procedure (PDWN). One patient with bleeding during operation (PDWN) was also treated with norepinephrine rinse, submucosal injection of epinephrine and electric coagulation, no other severe complications were found. There were no differences between VNTPS technique group and conventional ERCP group(13.3% vs 9.3%, χ2 = 0.478, P > 0.05). These finding suggest that VNTPST was one of the approaches when standard techniques failed.

The standard cannulation technique of ERCP can achieve satisfactory effects, especially application of ultra-slipping guide wire increases the successful rate for bile duct cannulation and declines the incidence of complications. In our study, 247 cases in TRERCP group were successfully treated with a successful rate of 89.1% (247/277). Complications occurred in 26 cases, the incidence of complications was 9.3% (26/277), which is consistent with the reported data both in China and in foreign countries[13-15].

Although the successful rate for standard ERCP is high at present, the selective bile duct cannulation failure rate is 5%-10%. Due to anatomic and physiological factors such as shortage of common cholangiopancreatic duct, duodenal diverticulum, small ampullary orifice, or cervical of the ampulla, it is difficult to perform selective biliary cannulation. Pathologic conditions, such as Oddi’s sphincer stenosis, duodenal inflammation, ampulla and papillary neoplasms, impacted calculi, may result in cannulation failure. However, VNTPST plays a salvage role in solving such cannulation difficulties. In our study, the successful rate was 80% (24/30)and the incidence of complication was 13.3% in VNTPST group, which is in line with the reported PSP both in China and in foreign countries[13,15-17], indicating that as long as precuts are skillfully performed, VNTPST is safe and effective and plays an important role in increasing the ERCP successful rate.

The precondition of PSP is that the tip of scalpel should be inserted into the papilla orifice. In general, it is often applied when pancreatic duct cannulation is performed repeatedly and TRERCP fails. The technique is suitable for type “Y” or type “V” pancreaticobiliary ductal junction, especially for type “Y”. The advantage of PSP is that the direction and depth are easy to control, but complications such as severe pancreatitis may occur, because pancreatic duct edema may occur after PSP[17]. In our study, the pure current was applied to the MPSP precut, and the direction of incision was made at the 10-11 o’clock direction, thus avoiding the occurrence of edema and trauma in pancreatic duct orifice and pancreatitis after MPSP. MPSP cannot be applied to the small papilla orifice since PLPTS cannot be inserted into the pancreatic duct. For type V in particular, sometimes it is not easy to achieve such a succees, PDWN or PUWN should be performed. For the impacted stones in duodenal ampulla or duodenal ampulla mass, it is not as convenient as needle knife.

Needle-knife is the major tool for precut[17]. In this study, needle knife was used in 19 cases (19/30, 63.3%) with PDWN or PUWN or PDGP or comprehensive technology, the successful rate was 68.4% (13/19). During the procedure, the tip of the needle should be put in the middle of visual area. If cannulation of the CBD through the opening is difficult, cannulation can be achieved with needle knife technique in most cases.

Due to carelessness of nurses, the soft wire was not replaced by a hard one. The tip of soft wire was broken off in the pancreatic duct (PDGP group) in 1 case, but there were no postoperative complications. Bleeding occurred in 1 case when small blood vessels were cut by needle-knife, but was stopped and no severe complication occurred. Our data indicate that NPK is as successful and safe as MPSP.

In Katsinelos study, 68 cases underwent needle knife precut, bleeding occurred in 5 cases (7%) and AP in 3 cases (4%), which were treated with conservative therapy[18]. The complication rate in our study was 13.3%, which is in line with the reported data[12], there were no severe complications or death, indicating that the procedure is highly successful and quite safe. Compared with TRERCP, postsphincterotomy hemorrhage often occurred after needle knife precut, but it was minor and able to be treated with epinephrine rinse or nephrine injection. One patient had hemorrhage in our study and no adverse effect was found after treatment. Abdominal pain should be closely observed after precut to avoid perforation for which an abdominal image is necessary. Once perforation occurs, titanium clips, gastrointestinal decompression and fast should be taken.

Compared with needle knife, although the depth of incision is easy to control and may not result in perforation, SNKP is not so convenient for duodenal ampulla calculus incarceration. When the direction is controlled by pancreatic duct guidewire, PDGP is good for protruded papilla but not for small aperture endoscope[19]. The papilla orifice often cannot be turned up for the duodenum adherence or malformation after abdominal part operation, UROT can move up the incision. When standard ERCP is difficult to turn up the papilla orifice, BERET can be performed. When the guide wire is inserted repeatedly into the pancreatic duct, PDGP can avoid repeated catheter insertion. When the bile cannulation is achieved, standard ERCP follows. To improve ERCP successful rate, when a single method cannot complete deep cannulation, CT can be used in various precuts to obtain cannulation.

The reasons for the failure of cannulation in all kinds of precut are as follows: The bile duct not found in 1 case of OSS combined with cholelocholithiasis, the bile duct distorted by neoplasm in 1 case of pancreatic head carcinoma, duodenal papilla carcinoma diagnosed in 2 cases, unnecessary precut, 1 case of distal bile duct cancer and distal stricture of CBD.

Based on our study, the operation indication should be strictly controlled[20]. Precutting should be avoided for diagnostic purposes because other available methods, such as MRCP and endosonography can provide diagnostic information. Precut should be avoided if the distal stricture of CBD is longer than 1.5 cm. When cannulnation of the common bile duct is not possible after precut, ERCP should be repeatedly performed 5-7 d later when edema caused by precut relieves and cannulation can be achieved.

In conclusion, needle knife technique can be performed when orifice cannot be exposed for the inflamed papilla or ampullary edema for which PSP is not available. The exposed length of needle knife is determined according to the size and shape of papilla. The isolating sheath should be fixed by nurse, otherwise intraperitoneal perforation may occur. Capillary hemorrhage in the NPK can be stopped by electric coagulation combined with needle knife. Perforation may occur in subsequent EST after the precut in patients with cholelithiasis, therefore, the incision size should not be too big in subsequent EST. The precut should be slowly extended step by step, from ampullary mucosa to submucosa in layers, finally ended up with a seepage of bile detected or the bile duct sphincter tissue seen. Both PUWN and PDWN can be used in patients with duodenal ampulla calculus incarceration, whereas PDWN should be carefully performed in patients with small papilla. When distal stenosis of CBD is too long, needle knife should be cautiously used. For a right bile orifice, opening of the bile ducts may be found in the right side of precut. PUWN is suitable for the small papilla with a small orifice.

McCune reported endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in 1968 for the first time, with the successful rate of 25%[1]. It was early applied in clinical practice in 1972[21], and the therapeutic ERCP (TERCP) was developed. Kawai and Nagai in Japan used endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) for acute obstructed suppurate cholangitis (AOSC) patients and achieved success in 1978. In China, ERCP was introduced into Peking Union Hospital in 1974. Dr. Ming-Zhang Chen initially reported endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), but it was not widely used for its complex technique and lower successful rate. With the advances in surgical techniques and equipments, the successful rate for ERCP was 84.0% in 1970s, and reached 93.5% in 1980s and 96.1% in 1990s in China[2], which is similar to the international reports[3,4]. TERCP was initially applied in early 1980s and has become an important method in treatment of biliary duct and pancreatic disorders. The therapeutic ERCP for patients with biliary duct and pancreatic disorders has achieved satisfactory curative effects on biliary duct and pancreatic diseases in China[8]. The successful rate for different diagnostic ERCP (DERCP) techniques depends on EST, which is associated with selective and deep cannulation of the bile duct. Due to anatomy, physiology factors and pathologic variation, the guide wire, catheter and scalpel cannot always be inserted into the bile duct successfully, leading to failure in TERCP. So it is the key step to various new type precut sphincterotomy techniques (VNTPST) in ERCP.

Precut was initially reported by Siegel[5], the successful rate for ERCP can go up with the success of precut. The so-call “precut” can be explained as following: when biliary cannulation is difficult to perform, papilla and bile duct sphincters need to be partially cut in advance for catheter insertion into the bile duct, then the procedures could be well done. So it is different from the general EST. It was reported that the successful rate for precut is 77%-91%[6,7]. The application of precut is limitted[8-11] because more complications occur. Since needle shape scalpel is very difficult to use and not safe during the precut papillotomy, few reports on its use are available.

We first designed and reported the mucosal bridge precut (Deng's precut) which is especially suitable for patients with inflamed papilla combined with up papillary diverticula. The technique can correct the cannulation angle, and make cannulation easy. It is safer than needle knife. We suggest that this procedure can be extensively used because it is of higher successful rate and safety.

The study suggests that when efforts using standard techniques have failed in ERCP and biliary access is required, Deng’s precut, a combined endoscopic “precut” technique is available. In experienced hands of ERCP, the ratio of ERCP can be increased with remarkable effects. Precuts appear to be as safe and effective as standard EST and can be widely performed in large and middle-sized hospitals.

VNTPST: various new type precut sphincterotomy techniques; MPSP: modified pancreatic sphincter precutting; PDWN: precut down with needle; NDF: needle knife; PUWN: precut up with needle; PDGP: pancreatic duct guideline precut; Deng’s precut: mucosal bridge precut; UROT: up removal orifice technique; BERET: bending endoscope or rotating endoscope technique; PDGC: pancreatic duct guideline cannulation

This is a well written paper. In the study, the authors retrospectively investigated the effect and safety of VNTPST in ERCP for difficult biliary duct cannulation (DBC). VNTPS and Deng’s precut are highly effective to get biliary access during ERCP for DBC. They can increase the successful rate for deep cannulation and decrease complications.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Li LJ

| 1. | Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater: a preliminary report. By William S. McCune, Paul E. Shorb, and Herbert Moscovitz, 1968. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:278-280. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sun ZX, Xu GM, Li ZS, Xie SQ, Wang N, Tian Q, Wu RP, Yao YZ, Fang YQ. Practical value of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary disease. Dier Junyi Daxue Xuebao. 1998;19:401-404. |

| 3. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Frank CD, Adler DG. Post-ERCP pancreatitis and its prevention. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:680-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siegel JH. Precut papillotomy: a method to improve success of ERCP and papillotomy. Endoscopy. 1980;12:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Uchida N, Tsutsui K, Kamada H, Ogawa M, Fukuma H, Ezaki T, Aritomo Y, Kobara H, Ono M, Morishita A. Pre-cutting using a noseless papillotome with independent lumens for contrast material and guidewire. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:947-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schwacha H, Allgaier HP, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Allgaier U, Blum HE. A sphincterotome-based technique for selective transpapillary common bile duct cannulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hu B, Zhou DY, Gong B, Wang SZ, Zhang FM, Wang XL. Application of precut sphincterotomy in the diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP : a report of 73 cases. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:1052-1054. |

| 9. | Qin MF, Zhou FS, Wang ZY, Fan JD, Lu HZ. Analysis of 691 cases underwent endoscopic pre-cut papillotomy. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2001;18:95-96. |

| 10. | Jiang CB, Wang JB. Analysis of precut papillotomy in endoscopy. Xiandai Shiyong Yixue. 2002;14:606. |

| 11. | Zhang BY, Tian FZ, Wang Y, Huang DR, Gong L. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with needle-shaped knife: report of 476 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:434-437. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Akashi R, Kiyozumi T, Jinnouchi K, Yoshida M, Adachi Y, Sagara K. Pancreatic sphincter precutting to gain selective access to the common bile duct: a series of 172 patients. Endoscopy. 2004;36:405-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ma SC, Yang XJ, Shen JW, Zhang XR, Zhang X Zhong B, Xie WF, Chen WZ, Shen YF, Li S. Analysis on 126 cases with bile duct diseases underwent sphincterotomy precut. GanDan YiWaike Zazhi. 1999;11:123-124. |

| 14. | Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, Wong RC, Ferrari AP, Montes H, Roston AD, Slivka A, Lichtenstein DR, Ruymann FW. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pungpapong S, Kongkam P, Rerknimitr R, Kullavanijaya P. Experience on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography at tertiary referral center in Thailand: risks and complications. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:238-246. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tang SJ, Haber GB, Kortan P, Zanati S, Cirocco M, Ennis M, Elfant A, Scheider D, Ter H, Dorais J. Precut papillotomy versus persistence in difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2005;37:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kahaleh M, Tokar J, Mullick T, Bickston SJ, Yeaton P. Prospective evaluation of pancreatic sphincterotomy as a precut technique for biliary cannulation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:971-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Katsinelos P, Mimidis K, Paroutoglou G, Christodoulou K, Pilpilidis I, Katsiba D, Kalomenopoulou M, Papagiannis A, Tsolkas P, Kapitsinis I. Needle-knife papillotomy: a safe and effective technique in experienced hands. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:349-352. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Draganov P, Devonshire DA, Cunningham JT. A new technique to assist in difficult bile duct cannulation at the time of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. JSLS. 2005;9:218-221. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Larkin CJ, Huibregtse K. Precut sphincterotomy: indications, pitfalls, and complications. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cotton PB. Cannulation of the papilla of Vater by endoscopy and retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Gut. 1972;13:1014-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |