Published online Aug 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i32.4372

Revised: April 10, 2007

Accepted: April 16, 2007

Published online: August 28, 2007

AIM: To compare the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy (CE) with that of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE).

METHODS: Pubmed, Embase, Elsevier ScienceDirect, the China Academic Journals Full-text Database, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register were searched for the trials comparing the yield of CE with that of DBE. Outcome measure was odds ratio (OR) of the yield. Fixed or random model method was used for data analysis.

RESULTS: Eight studies (n = 277) which prospectively compared the yield of CE and DBE were collected. The results of meta-analysis indicated that there was no difference between the yield of CE and DBE [170/277 vs 156/277, OR 1.21 (95% CI: 0.64-2.29)]. Based on sub analysis, the yield of CE was significantly higher than that of double-balloon enteroscopy without combination of oral and anal insertion approaches [137/219 vs 110/219, OR 1.67 (95% CI: 1.14-2.44), P < 0.01), but not superior to the yield of DBE with combination of the two insertion approaches [26/48 vs 37/48, OR 0.33 (95% CI: 0.05-2.21), P > 0.05)]. A focused meta-analysis of the fully published articles concerning obscure GI bleeding was also performed and showed similar results wherein the yield of CE was significantly higher than that of DBE without combination of oral and anal insertion approaches [118/191 vs 96/191, fixed model: OR 1.61 (95% CI: 1.07-2.43), P < 0.05)] and the yield of CE was significantly lower than that of DBE by oral and anal combinatory approaches [11/24 vs 21/24, fixed model: OR 0.12 (95% CI: 0.03-0.52), P < 0.01)].

CONCLUSION: With combination of oral and anal approaches, the yield of DBE might be at least as high as that of CE. Decisions made regarding the initial approach should depend on patient’s physical status, technology availability, patient’s preferences, and potential for therapeutic endoscopy.

- Citation: Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(32): 4372-4378

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i32/4372.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i32.4372

Small intestine is the middle part of digestive tract, due to its anatomic location, structural characteristics, and physiological functions, it is difficult to inspect via gastroscopy and colonoscopy. Push endoscopy is limited in that it only allows inspection of the proximal small intestine for variable distances. Intraoperative endoscopy has not met with widespread acceptance for the requirement of open laparotomy with surgically assisted passage of the endoscope through the intestine, although it has been considered the most reliable procedure for several years[1]. The diagnostic yield and accuracy of other modalities such as barium study, DSA, radionuclide and computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging is poor. All these make the management of small bowel disease exceptionally difficult.

The techniques of capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) are regarded as excellent tools for the diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disease, as well as for complementary procedures. Considerable research has demonstrated that they were more effective than other diagnostic modalities[2,3]. It’s confusing, however, when a choice should be made between the two advanced tools. Gay et al[4] concluded that indication and route for DBE could be determined according to the outcome of CE. The protocol has been widely accepted in developed countries and it seems effective, but it means that patients should undergo and pay for both of these two expensive items. It’s not clear whether the above protocol was a good choice judging from the cost benefit. The aim of the present study was to assess the diagnostic efficacy of CE and DBE and to determine the optimal diagnostic procedure for patients with small bowel disease.

Patients with symptoms indicating organic small bowel disease such as obscure GI bleeding, abdominal pain (functional GI diseases should be excluded), diarrhea etc., had been enrolled in the included studies, they had undergone gastroscopy, colonoscopy and other diagnostic modalities without positive findings.

The electronic databases: Pubmed (1966 to February, 2007), Embase (1980 to February, 2007), Elsevier ScienceDirect (1995 to February, 2007), the China Academic Journals Full-text Database (1979 to February, 2007), and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (Issue 1, 2007) were used for systematic literature searches. We employed the text words: capsule endoscopy, video capsule endoscopy combining with double-balloon endoscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy, push-and-pull enteroscopy, as search terms. The search of abstracts presented at the proceedings of Digestive Disease Week (USA) and the World Congress of Gastroenterology was also performed.

Literature was searched and prospective studies were collected. When two or more publications from one institution appeared to review the same patients, only the most recent study results were included. CE and DBE should be performed on each patient successively in included studies, so the diagnostic yields of two tests are able to be compared under equal conditions. All papers should be examined independently for eligibility by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third reviewer.

Data were entered into the Cochrane Collaboration review manager software RevMan 4.2.8 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, U.K.). The odds ratios of diagnostic yields of the two tests were examined as a measure of the outcome. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed by chi-square test. Statistical significance for the test of heterogeneity was set at 0.10. If significant heterogeneity exists, it would be inappropriate to combine the data for further analysis using a fixed-effects model, alternatively, the random model was used for calculations, then sub analyses for the meta-analysis was planned according to the cause of heterogeneity.

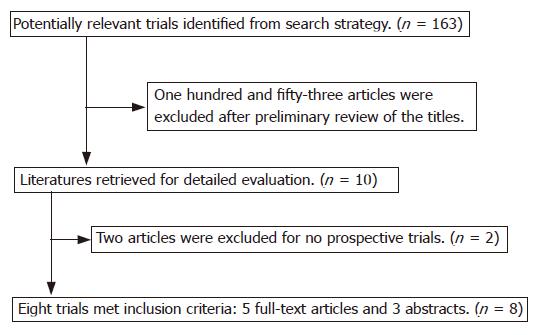

One hundred and sixty-three pieces of literature were initially identified using the search strategy described. One hundred and fifty-three articles were excluded after preliminary review for not having comparative studies, leaving 10 for detailed evaluation by two independent reviewers. Among these 10 potentially appropriate studies, an article retrospectively studied the yield of CE and DBE[5] and a review[6] were excluded. Finally, eight pieces of literature with 277 subjects met inclusion criteria, to include 5 fully published articles and 3 abstracts (Figure 1).

Most patients suffered obscure GI bleeding. Besides, two patients with diarrhea and one patient with unclear weight loss were included in Damian’s study[7]. Three patients in Wi’s study[8] complained of chronic abdominal pain, one of them was excluded from statistics because his final diagnosis was functional GI disease. Nine patients with polyposis in Matsumots’s study[9] were excluded from data analysis because their diagnosis had been made in advance and multi-segments of GI tract were involved.

In Nakamura’s study[10], two patients did not undergo DBE for severe cardiopulmonary impairment, one patient with anal bleeding was identified as having colon cancer before DBE, one patient suddenly declined DBE just before the examination, so the data of the 4 patients were deleted from statistical analysis. All patients of the other 7 studies underwent both CE and DBE.

Double blind method was used in five studies: physicians evaluating CE and DBE should be blinded to the results of the other method. Matsumoto et al[9] did not mention this aspect in their paper. In Mehdizadeh’s[11,12] study, CE was performed prior to DBE. In Hadithi’s trial[13], the endoscopists were aware of the identity and clinical presentations of the patients, and of the results of the VCE at the time of performing DBE, but the outcome of his study indicated that the detection rate of CE was superior to DBE. Lesions causing GI bleeding were classified and counted in six studies. Capsule retention occurred in three patients. No DBE related adverse events were reported (Table 1).

| Researcher (yr) | Case numberenrolled in study | Mean age | Male patientsnumber | Case numberenrolled in analysis | Positive findings | Complication | Double blindmethod |

| Kameda N[14] (2006)1 | 24 | 62 | 9 | 24 | 15/16 | 1/0 | Yes |

| Hadithi M (2006) | 35 | 63 | 22 | 35 | 28/21 | 0 | No |

| Nakamura M (2006) | 32 | 59 | 21 | 28 | 17/12 | 0 | Yes |

| Matsumoto T (2005) | 13 | 48 | 7 | 13 | 10/6 | 0 | Yes |

| Wi JH (2006)1 | 11 | 44 | 5 | 10 | 7/9 | 0 | Yes |

| Damian U (2006)1 | 28 | 60 | Not reported | 28 | 19/14 | 0 | Not reported |

| Mehdizadeh S (2006) | 188 | 58 | 85 | 115 | 63/57 | 0 | No |

| Zhong J[15] (2004) | 24 | 39 | 16 | 24 | 11/21 | 2/0 | Yes |

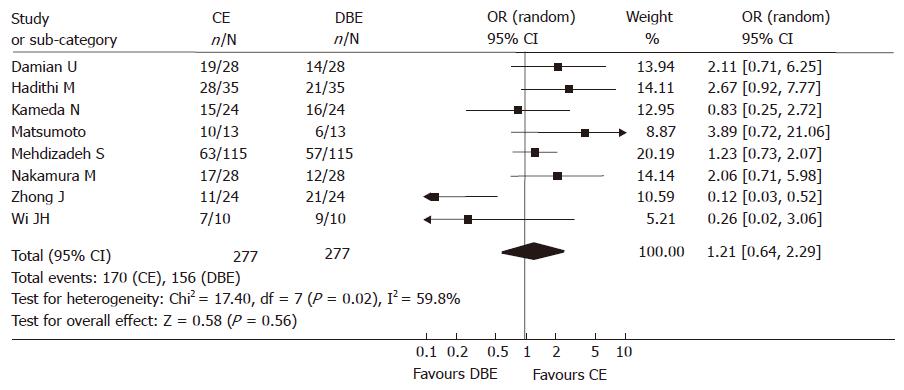

Among 277 subjects of the 8 studies, one hundred and seventy patients produced findings via CE and 156 by DBE. Homogeneity test of each OR displayed that heterogeneity did exist, the random model was used for calculations. The summary OR was 1.21 (95% CI: 0.64-2.29). There was no significant difference between the yield of CE and DBE (Figure 2).

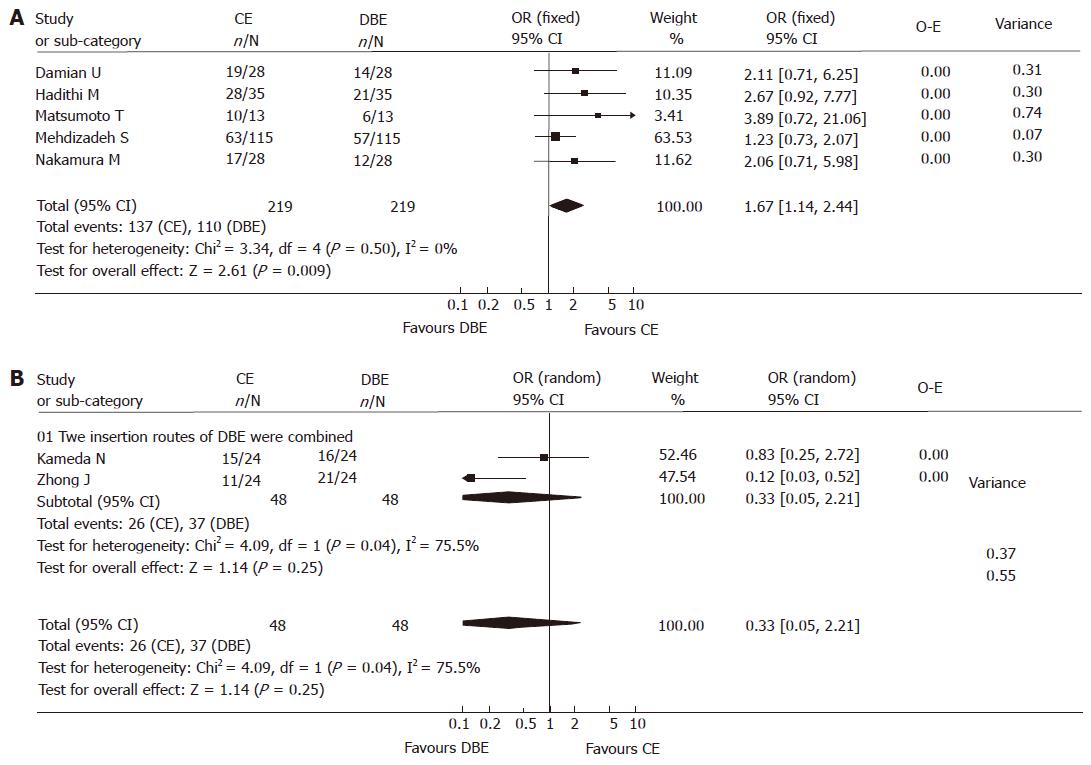

Homogeneity test displayed that there was heterogeneity in the meta-analysis. After reviewing each study intensively, we discovered that there were two insertion approaches applied in DBE procedures: oral and anal approaches. In some studies, two insertion approaches were combined: if no lesions were identified by one approach, the other one was performed, or all patients underwent both of the two approaches; in the other studies, most patients underwent just single DBE procedure, regardless of whether lesions were found or not. Single insertion approach could hardly cover the whole GI tract, so the detection rate it yielded was inevitably lower compared to the combination of both approaches. Therefore, we performed sub analysis according to the DBE insertion approaches used in each study. The method that DBE should be performed in each patient with combination of two insertion approaches was not used in 5 studies including 219 subjects, while the combination method was used in 2 studies including 48 subjects. Wi et al[8] did not mention the DBE insertion approaches used in his abstract, therefore the data was given up in further sub analyses. The result of sub analysis indicated that the yield of CE was significantly higher than that of DBE without the combination of the two insertion approaches [137/219 vs 110/219, fixed model: OR 1.67 (95% CI: 1.14, 2.44), P < 0.01)] (Figure 3A); while the detection rate of DBE with combinatory oral and anal routes was higher, though not significantly, than that of CE, [26/48 vs 37/48, random model: OR 0.33 (95% CI: 0.05, 2.21), P > 0.05)] (Figure 3B). Unfortunately, the sample size in this study was not large enough to lead to an absolute conclusion, we expect that this difference will tell us more if the we enlarge the sample size.

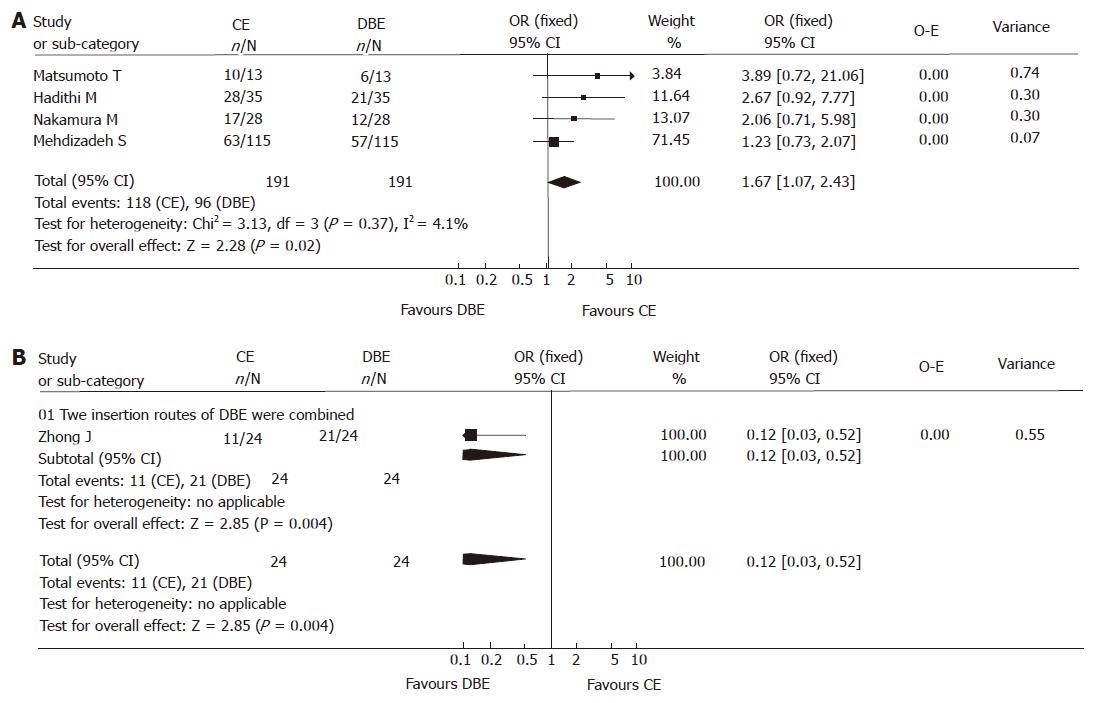

Since meta-analyses are rigorous exercises that need to be subject to peer review, it seems that the data of abstracts from national meetings may not be reliable; abdominal pain and diarrhea will have incredibly low yields on DBE and CE and most will be functional, therefore, we focused the analysis on the fully published papers concerning obscure bleeding. Focused analysis also revealed the significantly higher yield of CE compared to DBE when the combination of two approaches was not used [118/191 vs 96/191, fixed model: OR 1.61 (95% CI: 1.07, 2.43), P < 0.05)] (Figure 4A); and the yield of CE was significantly lower than that of DBE when combinatory insertion approaches were used [11/24 vs 21/24, fixed model: OR 0.12 (95% CI: 0.03-0.52), P < 0.01)], just one study was included however (Figure 4B).

Lesions detected in 239 patients with obscure GI bleeding were gathered from 6 studies and counting statistics were calculated. There was no significant difference in detection rate of various lesions listed below between the two endoscopies. (SPSS11.0, chi-square test, The P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant, (Table 2).

| CE | DBE | P value | |

| Angiodysplasia or phlebangioma | 76 | 62 | 0.189 |

| Tumor | 15 | 23 | 0.236 |

| Polyp | 9 | 2 | 0.062 |

| Ulcer | 20 | 20 | 1 |

| Erosion | 11 | 4 | 0.113 |

| Crohn disease | 4 | 7 | 0.544 |

| Diverticulum | 1 | 5 | 0.216 |

| Fresh blood and clot or red spot | 7 | 2 | 0.176 |

| Others | 3 | 7 | 0.339 |

| Total | 146 | 132 | 0.228 |

| Patients number | 239 | 239 |

CE and DBE are both advanced inspection items. They have common indications and quite different features. CE can cover the whole GI tract; the procedure requires no sedation[6] and is better tolerated. Its major limitations are the inability to obtain a biopsy, precisely localize a lesion, or perform therapeutic endoscopy. Additionally, it may provide false-positive and false-negative findings due to its incontrollable movement and low-resolution pictures it takes. It was recently reported that CE missed an advanced small-intestinal cancer that was later diagnosed with push enteroscopy[16], suggesting that CE is not an exclusive procedure but should instead be complementary to other diagnostic tools in the assessment of small intestinal pathology. On the contrary, DBE has more advantages in that it is much better adjusted because the movement of the scope can be handled according to the viewing angle and observation time needed; it can provide high-quality pictures, biopsy availability and therapeutic endoscopy[17,18]. DBE can be considered the gold standard if the whole small intestine were inspected. It appears to be equally as effective for the management of small-bowel lesions compared with intraoperative enteroscopy, and is associated with fewer complications[19,20]. Alternatively, it is not able to visualize the whole GI tract unless a combination of oral and anal insertion approaches is performed. The procedure is invasive and not as well tolerated as CE, requiring additional staff, typically two physicians or an additional nursing assistant.

The meta-analysis indicated that the yield of CE was higher compared to DBE with a single insertion approach, but might be lower than that of DBE with a combination of oral and anal approaches. Currently, most patients will have DBE that is capsule-directed, and therefore physicians should be able to find the majority of lesions that are causing bleeding, taking into account that the course is less invasive and more likely to be accepted. Though CE is a highly sensitive modality for the diagnosis of small bowel disease, it cannot always provide a right instruction for DBE due to the potential false-positive and false-negative findings produced. In Mehdizadeh’s series, CE found a potential bleeding source in 63 patients, but 22 (34.9%) of them received negative results in the following DBE procedure. In Hadithi’s series, eight (28.6%) patients had positive findings on CE, whereas these lesions could not be verified by DBE. The inclusion of all lesions detected by CE, even trivial, may partly explain the large number of false positives. The fact that in the majority of cases DBE actually visualized only the jejunum, thereby decreasing its detection rate may provide an alternate explanation. It is clear that a single insertion procedure of DBE could not provide a full-scale evaluation for the multi-segment involving or multi-segment originating diseases like Crohn’s disease and polyposis. In fact, we cannot determine whether an identified lesion is localized until the whole GI tract was inspected, therefore a second DBE should usually be considered. The procedure of DBE in combination with the two insertion approaches may prove to be more sensitive and the outcomes would be more reliable. At the same time, there will be no need for the course and charge of CE if the diagnosis was made by a single DBE procedure or when a second DBE could not be avoided. This would be more economical in some countries like China (Table 3).

| Cost per patient evaluated (RMB: Yuan) | |

| CE | 8500 |

| DBE | 3746 |

| CE + DBE × 1 | 12246 |

| CE + DBE × 2 | 15992 |

| DBE × 2 | 7492 |

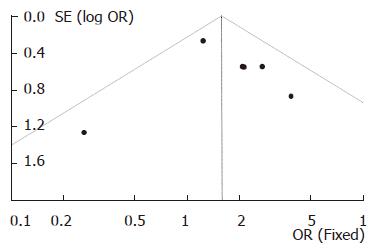

Funnel plot (Figure 5) for the analysis of publication bias was performed on the six studies in which the DBE was carried out with single insertion approach, visual inspection of the plot revealed no evidence of publication bias. The number of the fully published papers was too small to analyze the publication bias and more studies on comparison of the yield of DBE with combinatory insertion approaches to CE are needed.

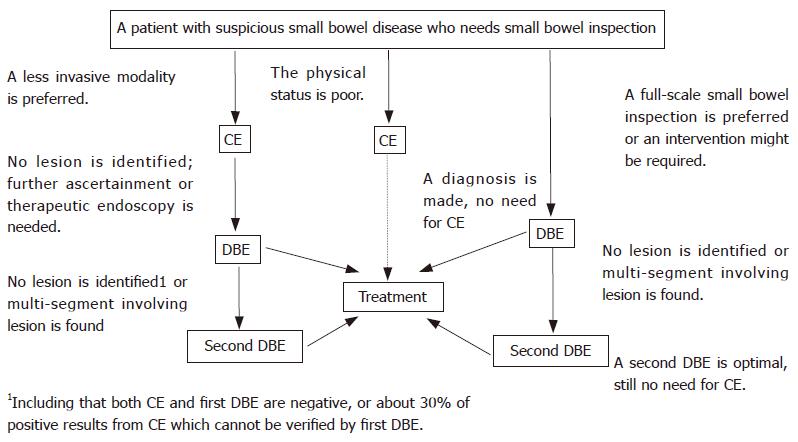

In summary, our study displayed that CE and DBE are both effective modalities for diagnosis of small bowel diseases. A capsule-directed DBE procedure might be better tolerated; the procedure of DBE with combination of oral and anal approaches might be more sensitive and the outcome might be more reliable (Figure 6). Choice for initial test should depend on patient’s physical status, available technology, patient’s preferences, and potential for therapeutic endoscopy. On the other hand, more studies are needed to evaluate the yield and accuracy of DBE with combinatory oral and anal insertion approaches compared to CE.

Small intestine is the middle part of digestive tract which is hard to be inspected by conventional diagnostic modality. Capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy, which are regarded as excellent tools for the diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disease, have common indications and quite different features. How should we make a choice between the two diagnosis modality?

The existing study concluded that indication and route for DBE could be determined according to the outcome of CE, which has been widely accepted in developed countries.

The meta-analysis evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of CE compared to DBE and systematically summarized the included clinical trials and related literatures.

The outcome of the meta-analysis is of referential value for management of small bowel disease. The choice between the two endoscopies could be made according to their diagnostic efficacy, cost benefit and patient’s tolerability.

The term yield in the meta-analysis means the detection rate of capsule endoscopy or double-balloon enteroscopy, no matter the positive findings are true-positive or false-positive.

The manuscript describes an interesting meta-analysis that is of outstanding relevance, well conducted, finely written and done according to a rigorous methodology.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Li M E- Editor Li JL

| 1. | Delmotte JS, Gay GJ, Houcke PH, Mesnard Y. Intraoperative endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:61-69. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Ell C. Prospective comparison of push enteroscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2016-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Fassler I. Outcome of capsule endoscopy in determining indication and route for push-and-pull enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Masatsugu Shiba, Kazuhide Higuchi, Natsuhiko Kameda, Kaori Kadouchi, Hirohisa Machida, Kazuki Yamamori, Hirotoshi Okazaki, Masaki Hamaguchi, Tomoko Wada, Yoshio Jinnno. Wireless Capsule Endoscopy and Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Japanese Patients with Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB182. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Gerson LB, Van Dam J. Wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;7:130-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Damian U, Schilling D, Hartmann D, Weickertb U, Eickhoff A, Jakobs R, Kudis V, Riemann JF. Double- Balloon Enteroscopy (Push and Pull Enteroscopy) of the Small Bowel: Comparison with Video Capsule Endoscopy and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB174. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Wi JH, Kim JO, Eun SH, Kim SY, Jung IS, Ko BM, Cho JY, Lee JS, Lee MS, Shim CS, Kim BS. A Prospective Comparison of Capsule Endoscopy and Double Balloon Enteroscopy in Small Bowel Disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB175. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Nakamura S, Iida M. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy with the double-balloon method in patients with obscure bleeding and polyposis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:827-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nakamura M, Niwa Y, Ohmiya N, Miyahara R, Ohashi A, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Goto H. Preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Endoscopy. 2006;38:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mehdizadeh S, Ross AS, Leighton J, Kamal A, Chen A, Schembre D, Binmoeller K, Kozarek R, Waxman I, Gerson L. Double Balloon Enteroscopy (DBE) Compared to Capsule Endoscopy (CE) Among Patients with Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding (OGIB): A Multicenter U.S. Experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB90. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, Gerson L, Leighton J, Chen A, Schembre D, Chen G, Semrad C, Kamal A, Harrison EM. What is the learning curve associated with double-balloon enteroscopy? Technical details and early experience in 6 U.S. tertiary care centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:740-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hadithi M, Heine GD, Jacobs MA, van Bodegraven AA, Mulder CJ. A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kameda N, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Tabuchi M, Sugimori S, Yukawa T, Kadouchi K, Okazaki H, Machida H, Inagawa M, Wada T, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Fujiwara Y, Oshitani N, Arakawa T. A Prospective Trial Comparing Wireless Capsule Endoscopy and Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Patients with Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB162. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Zhong J, Zhang CL, Ma TL, Jin CR, Wu YL, Jang SH. Comparative study of double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in etiological diagnosis of small intestine bleeding. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2004;24:741-744. |

| 16. | Madisch A, Schimming W, Kinzel F, Schneider R, Aust D, Ockert DM, Laniado M, Ehninger G, Miehlke S. Locally advanced small-bowel adenocarcinoma missed primarily by capsule endoscopy but diagnosed by push enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:861-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kita H, Yamamoto H. Double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:179-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamoto H, Kita H. Double-balloon endoscopy. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gerson LB. Double-balloon enteroscopy: the new gold standard for small-bowel imaging? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy (push-and-pull enteroscopy) of the small bowel: feasibility and diagnostic and therapeutic yield in patients with suspected small bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |