CASE REPORT

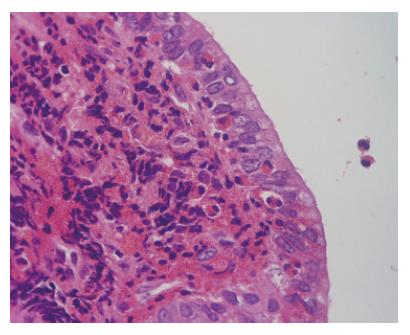

A 38-year-old woman was referred to our hospital due to epigastralgia and back pain of 3 d duration. On admission, physical examination revealed jaundice and epigastric tenderness. For 4 mo, the patient had been taking salazosulfapyridine (SASP) and teprenone for the treatment of suspected rheumatoid arthritis. The total leukocyte count was 4700/mm3 (44.8% neutrophils, 15.3% eosinophils). Blood chemistry showed: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 151 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 400 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 945 U/L; total bilirubin, 6.63 mg/dL, with direct bilirubin, 4.48 mg/dL; and IgG, 812 mg/dL (normal, 870-1700). Tumor marker results were: CA19-9, 125.9 mg/L (normal, ≤ 37). Antinuclear antibodies and P-ANCA were negative. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showed a dilated bile duct from the porta hepatis to the right and left lobes. A solid lesion was seen in the extrahepatic bile duct, which was slightly enhanced by the contrast medium. The gallbladder did not appear swollen, and paraaortic lymphadenopathy was noted. Ultrasound (US) examination revealed an isoechoic solid lesion in the common hepatic duct, with irregular wall thickening of the left hepatic duct. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS), using Levovist (Schering, Berlin, Germany), demonstrated that the wall of the intrahepatic bile ducts was thickened from the hilar region to the periphery with dilatation; a well-enhanced lesion was also seen (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed severe narrowing from the common hepatic duct to the porta hepatis with dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 2). Cholangioscopy revealed erythematous and edematous mucosa with stenosis at the lesion. On intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS), a solid, isoechoic lesion was seen around the common hepatic duct. Following transpapillary bile duct biopsy, a plastic stent was placed. On histopathological examination, the specimen had marked eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration into the biliary epithelium without evidence of malignancy (Figure 3). A diagnosis of eosinophilic cholangitis was made based on the histopathological findings and the presence of eosinophilia. The patient was started on prednisolone, 60 mg/d intravenously; the dosage was tapered down by 10 mg every week. Five weeks later, the serum bilirubin level and the eosinophil count decreased to within the normal range. The patient had a repeat ERCP; after removal of the plastic stent, the stenotic lesion was found to have improved markedly. The patient was discharged on the 55th hospital day. Five months later, follow-up ERCP showed that the stenosis had disappeared.

Figure 1 Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) showing thickened wall of intrahepatic bile ducts (from hilar to peripheral) with dilation, and the lesion was well enhanced.

Figure 2 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showing severe narrowing from common hepatic duct to porta hepatis with dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts.

Figure 3 Histopathological examination showing marked eosinophils and lymphocytes infiltration in biliary epithelium.

DISCUSSION

Eosinophilic pneumonia and eosinophilic gastroenteritis are well known as disorders associated with eosinophilic infiltration. When eosinophilic infiltration localizes in the bile duct, it is called eosinophilic cholangitis. When it involves the gallbladder, it is called eosinophilic cholecystitis. “Eosinophilic cholangiopathy” involves both. To the best of our knowledge, there have been 36 cases of eosinophilic cholangiopathy reported previously; 15 of the 36 cases were reported as having eosinophilic cholangitis[1-14]. Leegaard first reported eosinophilic cholangitis in 1980[1]. Though the lesion involved the 4 cases after having had only a cholecystectomy or stenting[2-5]. Eosinophilic cholangitis is a rare benign disorder that can be considered to be a self-limited disease. The other patients were treated with hepaticojejunostomy[6], hydroxyurea[7], and steroid[8-12]. Both steroid administration and cholecystectomy underwent in 3 cases[1,13,14].

The cause of eosinophilic cholangitis is unknown. In some reports, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) has been mentioned as possible cause. The diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome is based on the following criteria[15]: (1) sustained eosinophilia (more than 1500 eosinophils per cubic millimeter) for more than 6 mo; (2) the absence of other causes of eosinophilia, including parasitic infections and allergies; and (3) signs and symptoms of organ involvement. Since all reported cases do not appear to have completely met the criteria for HES except for one case[10], the relationship between eosinophilic cholangitis and HES is uncertain. Parasites, collagen diseases, and malignancy may lead to eosinophilia. Though none of these three conditions was present in the previously reported patients, 3 cases of eosinophilic cholecystitis with parasites have been reported[16-18]. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is thought to be associated with eosinophilic cholangitis, and it is assumed to be related to an allergic mechanism in 37%-41% of cases[19]. One reported case of eosinophilic cholecystitis was suspected to have been caused by a drug-induced reaction[20]. Our patient had a history of allergies, and her serum IgE was 648 mg/dL (normal, < 400). She had been taking sulfasalazine (SASP). Of note, SASP had been prescribed in one of the previously reported cases[7], and aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) had been prescribed in another case[9]. Ten cases of eosinophilic pneumonia have been reported as a side effect of SASP by Parry et al[21]. These results suggest that there is a relationship between eosinophilic cholangitis and SASP.

In our case, the diagnosis of eosinophilic cholangitis was made based on the presence of eosinophilia, the reversibility of the biliary stenosis with steroid treatment, and the eosinophilic infiltration in the biliary epithelium. 11/15 previously reported cases of eosinophilic cholangitis had eosinophilia. However, eosinophilia may not be necessary for diagnosing eosinophilic cholangitis, since not all cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis present with eosinophilia. In our opinion, the following findings are important for making the diagnosis: (1) wall thickening or stenosis of the biliary system; (2) histopathological findings of eosinophilic infiltration; and (3) reversibility of biliary abnormalities without treatment or following steroid treatment. Abdominal pain was present in 12/18 cases and should be taken into account when making the diagnosis.

Song et al[5] suggested that bile duct wall thickening was a characteristic finding of eosinophilic cholangitis on US and CECT. Irregular narrowing of the bile duct can be seen on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)[22]. In our case, the common bile duct was slightly enhanced, and cystic duct wall thickening on CECT. However, it is difficult to make a diagnosis based on only these imaging findings, since CT, ERCP, and MRCP have limited spatial resolution. Therefore, CEUS, cholangioscopy, and IDUS were done. This is the first reported case of eosinophilic cholangitis to have been fully investigated using all these modalities. CEUS has a high spatial resolution and can detect blood flow[23]. In our patient, a parenchymal echo was visualized in the common bile duct on CEUS; staining of the lesion along the intrahepatic bile ducts was considered to be a characteristic finding of eosinophilic cholangitis in this case. This finding enabled us to exclude malignancy. On cholangioscopy, mucosal erythema and stenosis were found. Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) revealed hypertrophic stenosis of the extrahepatic bile duct. Though concentric wall thickening was similar to autoimmune pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis, the stenosis was more extensive in our case. After prednisolone treatment, the patient’s biliary stenosis improved. The ERCP done 5 wk later still showed a mild localized stenosis of the intrahepatic bile ducts, and on histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen obtained at that time, slight eosinophilic infiltration was noted. Given the possibility of recurrence in other organs[3,9], the patient requires long-term follow-up. It is usually difficult to diagnose benign biliary stenosis. Since the patient’s quality of life after discharge depends on whether medical therapy or surgery is chosen, therapy should be chosen carefully.