Published online Mar 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1837

Revised: December 23, 2006

Accepted: February 7, 2007

Published online: March 28, 2007

AIM: To investigate the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) in prevention and control of liver fluke infection in northeast Thailand.

METHODS: A descriptive KAP survey pertaining to liver fluke infection was carried out in June 2005 to October 2006 using structured questionnaires. Data were collected by questionnaires consisting of general parameters, knowledge, attitude, practice, and a history of participation in the prevention and control of liver fluke infection.

RESULTS: A total of 1077 persons who were inter-viewed and completed the questionnaires were enrolled in the study. The majority were females (69.5%) and many of them were 15-20 years of age (37.26%). The questionnaires revealed that information resources on liver fluke infection included local public health volunteers (31.37%), public health officers (18.72%), televisions (14.38%), local heads of sub-districts (12.31%), doctors and nurses (9.18%), newspaper (5.72), internets (5.37%), and others (12.95%). Fifty-five point eleven percent of the population had a good level of liver fluke knowledge concerning the mode of disease transmission and 79.72% of the population had a good level of prevention and control knowledge with regards to defecation and consumption. The attitude and practice in liver fluke prevention and control were also at a good level with a positive awareness, participation, and satisfaction of 72.1% and 60.83% of the persons studied. However, good health behavior was found in 39.26% and 41.42% of the persons studied who had unhygienic defecation and ate raw cyprinoid’s fish. The result also showed that 41.25% of the persons studied previously joined prevention and control campaigns.

CONCLUSION: The persons studied have a high level of liver fluke knowledge and positive attitude. However, improvement is required regarding personal hygiene specifically with hygienic defecation and consumption of undercooked fish.

- Citation: Kaewpitoon N, Kaewpitoon SJ, Pengsaa P, Pilasri C. Knowledge, attitude and practice related to liver fluke infection in northeast Thailand. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(12): 1837-1840

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i12/1837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1837

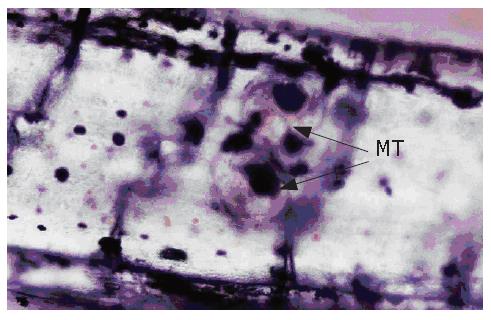

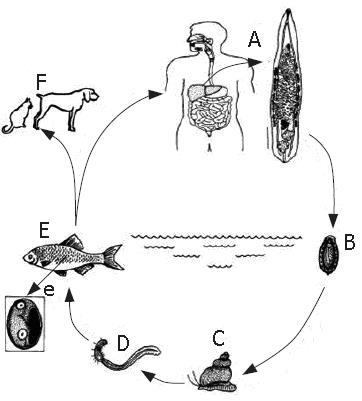

Liver fluke infection caused by O. viverrini remains a major public health problem in many parts of Southeast Asia including Thailand, Lao PDR, Vietnam and Cambodia[1]. Infection is acquired by ingestion of undercooked cyprinoid’s fish harboring infective metacercariae (Figure 1)[2]. Liver fluke is endemic among human populations in northeast and north Thailand, where the most common raw fish “Koi pla” is frequently consumed[3-6]. In central Thailand where no indigenous human infection is ever encountered, cats and dogs are found to be naturally infected with human liver fluke (Figure 2). In the south, no infection is encountered. It has been extensively studied in Thailand where about 6 million people are infected with liver fluke accounting for 9.4% prevalence within the population in 2001[2,5-8]. The infection is associated with a number of hepatobiliary diseases, including cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis[9]. Moreover, both experimental and epidemiological evidence strongly implicates that liver fluke infection is the etiology of cholangiocarcinoma, bile duct cancer development[10,11].

A community-level health education campaign has been conducted since late 1950s. Liver fluke control has been started as a small scale helminthiasis control program in some high risk areas. Presently, the program is operated in some provinces of the central and all provinces of the northeast and north of Thailand. The main strategies for liver fluke control comprise three interrelated approaches, namely stool examination and treatment of positive cases with praziquantel for eliminating human host reservoir, health education for a promotion of cooked fish consumption to prevent infection, and improvement of hygienic defecation for the interruption of disease transmission. Between 1984 and 1987, the positive rate of liver fluke infection was 63.6%. In 1988, the positive rate went down to 35.6%. When the region wide control program was started in 1989, the annual positive rate decreased to 9.4% in 2001[8]. The overall prevalence indicates a considerable decrease of liver fluke in the region. However, the positive rates for several provinces remain high. Published studies provide biology, disease, diagnosis and treatment but the survey related to knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) on liver fluke infection is weak and inconclusive. KAP on prevention and control of liver fluke infection are essential for decreasing the disease and planning of government. Also, no recent and update study has shown the data on KAP in northeast Thailand by questionnaires obtaining the general data, knowledge, attitude, practice, and a history of participation in the prevention and control of this parasite.

The study was conducted in Ubon Ratchathani Province which is situated 630 km from Bangkok (central region) of Thailand. This province is located in the northeast broader line with Laos PDR (Figure 3). The geographic area has two rivers, namely Moon and Mae Kong where many people habit at the side of 2 main rivers. The infection rate of liver fluke in Ubon Rathcathani Province has been 19.5% in all age groups since 1997[12]. According to the Department of Communicable Disease Control, the prevalence of liver fluke infection is 12.8%[13].

A descriptive KAP survey pertaining to liver fluke was carried out in June 2005 to October 2006 using structured questionnaires administered by the research officers and trained research assistants. Persons enrolled in this study were from TaLad, KuMeung, NongKinPen, BungWai, NonPueng, KamKwang, and Srikai sub-District of WarinChamRap District, and HuaRue sub-District of Ubon Ratchathani District, Ubon Ratchathani Province in the northeast Thailand. Data were collected by Questionnaires. Before the study, permission and collaboration of the head of the public health centre and/or head of the sub-district were obtained. The questionnaire was tested before the study. The interviewers received an interview training of 1 d. The study was conducted at weekends to increase the possibility of meeting people at home. The staff comprised 3 interview teams each consisting of 5 interviewers from college of medicine and public health. Each team was responsible for a number of households in the sub-district. A supervising team visited the members of each interview team to check their performance and questionnaires were checked for inconsistencies. When correction was deemed necessary, the interview team visited the study participants on the same day again to gather the missing information. All inhabitants in a study site were asked to participate in the study. A total of 1077 persons were included. Written informed consent was obtained (those who could not write gave a fingerprint). Persons were asked about their KAP of liver fluke by a structured questionnaire. KAP of liver fluke were measured by asking questions related to the disease, mode of disease transmission, treatment, personal hygiene, and a history of participation in the prevention and control of Liver fluke. All questions related to KAP were multiple choices and open questions.

Data from structured interviews were analyzed using SPSS/PC version 5. Knowledge variables were summed up into a composite score and ranked as poor and good scores (lower or higher than the median score) with a range of 17 to 23. Attitudinal questions were structured in a 3 point Likert scale responses comprising agreement, disagreement and unawareness. The resulting score ranged from 1 to 3. The measure of internal consistency showed an acceptable level of reliability.

A total of 1077 persons who were interviewed participated in the study and completed the questionnaires. Females accounted for 69.5% and males 30.5%. The age of the majority persons was 15-20 years. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the persons older than 14 years in the eight sub-districts of the persons studied. Most of the persons were farmers (43.67%) and students (38.47%). Regarding the educational level, 95.64% completed primary school, middle and higher school education and could read and write. The questionnaires revealed that information resources on liver fluke infection included local public health volunteers (31.37%), public health officers (18.72%), televisions (14.38%), local heads of sub-districts (12.31%), doctors and nurses (9.18%), newspaper (5.72), internets (5.37%), and others (12.95%) (Table 2). In this survey, local public health volunteers were the main information resource. However, improvement was required regarding liver fluke knowledge especially with the disease transmission, prevention and control. Of the persons studied, 55.11% had a good level of liver fluke knowledge concerning the mode of disease transmission (Table 3), 79.72% had a good level of prevention and control knowledge with regards to defecation and consumption (data not show). Generally, the majority of the persons studied had a positive attitude towards liver fluke prevention and control. A good level of liver fluke prevention and control knowledge was found in 72.1% of the persons studied with a positive awareness, and satisfaction. Hygienic defecation was found in 60.83% of the persons studied, unhygienic defecation in 39.26% of the persons studied (Table 4). The risk food consumption was found in 27.38% and 14.04% of the persons studied who ate raw cyprinoid’s fish 1 time/mo and ≥ 2 times/mo, the intermediate hosts of liver fluke accounted for 27.38% and 14.04%, respectively. The questionnaire revealed that 20.12% of the persons studied were infected with liver fluke, O. viverrini (data not shown). The result also showed that 41.25% of the persons studied previously joined prevention and control campaigns.

| Characteristic | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 328 | 30.5 |

| Female | 749 | 69.5 P < 0.05 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| 15-20 | 401 | 37.26 P < 0.05 |

| 21-30 | 127 | 11.79 |

| 31-40 | 166 | 15.42 |

| 41-50 | 129 | 11.96 |

| 51-60 | 133 | 12.31 |

| > 60 | 121 | 11.26 |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmer | 470 | 43.67 P < 0.05 |

| Trader | 52 | 4.85 |

| Housewife/unemployed | 45 | 4.16 |

| Employee | 47 | 4.34 |

| Student | 414 | 38.47 P < 0.05 |

| Other | 49 | 4.51 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 47 | 4.36 |

| Can read and write primary | 564 | 52.37 P < 0.05 |

| Middle and high | 466 | 43.27 |

| Information resources | n | % |

| Local head of sub-district | 133 | 12.31 |

| Local public health volunteer | 338 | 31.37 P < 0.05 |

| Public health officer | 202 | 18.72 |

| Doctor and Nurse | 99 | 9.18 |

| Television | 155 | 14.38 |

| Internet | 58 | 5.37 |

| Newspaper | 61 | 5.72 |

| Others | 31 | 2.95 |

| Total | 1077 | 100 |

| Level | n | % |

| Knowledge | ||

| Good | 594 | 55.11 P < 0.05 |

| Fair | 306 | 28.42 |

| Poor | 177 | 16.47 |

| Attitude level | ||

| Good | 777 | 72.1 P < 0.05 |

| Fair | 211 | 19.58 |

| Poor | 89 | 8.32 |

| Behavior | n | % |

| Health behavior | ||

| Mostly hygienic defecation | 655 | 60.83 P < 0.05 |

| Occasionally unhygienic defecation | 246 | 22.8 |

| Frequently unhygienic defecation | 176 | 16.46 |

| Risk behavior: risk food consumption | ||

| Low risk | 631 | 58.58 P < 0.05 |

| Moderate risk (1 time/mo) | 295 | 27.38 |

| High risk (> 1 time/mo) | 151 | 14.04 |

| Joined the prevention and control campaigns | ||

| Yes | 444 | 41.25 |

| No | 633 | 58.75 |

Eating raw or improperly cooked food including meat and fish is a source of infection with many parasitic zoonoses. The tradition of eating raw fish is becoming increasingly fashionable in many countries, principally with foods such as sushi, sashimi, koi-pla, kinilaw and ceviche. This has led to a dramatic rise in the incidence of fish borne zoonotic parasitic infections in previously uninfected ethnic groups. Consumption of raw or improperly cooked or pickled freshwater fish results in about 70-100 million people infected with trematodes Clonorchis sp. Opisthorchis spp. Echinostoma spp. Control is through treatment with praziquantel, sanitation and education to discourage the consumption of raw fish. In Southeast Asia the prevalence is declining slowly due to effective and relatively cheap drugs and reduction in the use of night soil to fertilize fish ponds. A better sewage treatment system is required if the prevalence declines further[14]. A 10-year control program to alter raw fish eating habits in northeast Thailand has managed to reduce the regular consumption of raw fish, but occasional consumption of raw fish remains unchanged[12]. Opisthorchiasis is one of the diseases of public health importance in Thailand. It has been estimated that approximately 6 million people in Thailand harbor liver fluke[8]. Although the mortality rate is not high, the morbidity causes increased loss of man power (work days lost) and economic problems. The infection with liver fluke is common among the rural people of Northeast Thailand, which is associated with cholangiocarcinoma[10,11]. The majority of the people in Ubon Ratchathani Province have no clear-cut knowledge on transmission of liver fluke. Some (44.9%) still have incorrect knowledge about eating undercooked cyprinoid’s fish. They also have incorrect knowledge about cooking raw fish with lemon and ant, considering that it can lead to infective stage of dead live fluke. These findings are consistent with the study of risk food consumption among northeasterner[13]. It might be one of the possible explanations for the failure to decrease liver fluke infection in the risk areas. Moreover, they also have incorrect knowledge about the fact that liver fluke infection is associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Those with misbelieve should be considered as the important target group that needs to promote their knowledge on transmission of liver fluke and related diseases so as to remove the potential barriers in control of liver fluke in the community. A positive attitude towards liver fluke prevention and control was found in 72.1% of the persons studied with a positive awareness of and participation in liver fluke disease prevention and control and participation in liver fluke disease prevention and control. However, 8.32% of the persons studied still had a poor attitude towards liver fluke prevention and control with awareness of and participation in liver fluke disease prevention and control, suggesting that personal hygiene specifically with the consumption of undercooked fish and liver fluke-associated with diseases should be improved. The percentage of people who have unhygienic defecation is 39.26%. Health history data obtained from questionnaires and interviews showed that 20.12% of the persons studied were infected with O. viverrini, which is consistent with reported data[8]. In the present study, 41.42% of the persons studied had consumption of undercooked cyprinoid’s fish that may infect liver fluke. The result also showed that 58.75% of the persons did not join prevention and control campaigns, suggesting that it is necessary to increase the community awareness of the transmission of the disease in people who lack the knowledge about liver fluke. Local public health services with health education and mobile stool examination should be strengthened.

In conclusion, the population has a good level of liver fluke knowledge and positive attitude towards liver fluke prevention and control. However, improvement is required regarding personal hygiene specifically with hygienic defecation and consumption of undercooked fish.

The authors thank Professor Dr. Malcom Moore for helping the English-language presentation of the manuscript.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Che YB

| 1. | Infection with liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini, Opisthorchis felineus and Clonorchis sinensis). IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:121-175. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kaewkes S. Taxonomy and biology of liver flukes. Acta Trop. 2003;88:177-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Harinasuta C, Vajrasthira S. Opisthorchiasis in Thailand. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1960;54:100-105. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Wykoff DE, Harinasuta C, Juttijutada P, Winn MM. Opisthorchis viverrini in Thailand-the life cycle and com-parison with O. felineus. J Parasitol. 1965;51:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Preuksaraj S, Jeeradit C, Satilthai A, Sidofrusmi T, Kijwanee S. Prevalence and intensity of intestinal helminthiasis in rural Thailand. Con Dis J. 1982;8:221-269. |

| 7. | Harinasuta C, Vajrasthira S. Study on opisthorchiasis in Thailand: survey of the incidence of opisthorchiasis in patients of fifteen hospitals in the northeast. In: Proceeding of the 9th Pacific Science Congress; Bangkok 1962; 166-171. |

| 8. | Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. Opisthorchiasis control in Thailand. Acta Trop. 2003;88:229-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harinasuta C, Harinasuta T. Opisthorchis viverrini: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Thailand. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1164-1167. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Thamavit W, Bhamarapravati N, Sahaphong S, Vajrasthira S, Angsubhakorn S. Effects of dimethylnitrosamine on induction of cholangiocarcinoma in Opisthorchis viverrini-infected Syrian golden hamsters. Cancer Res. 1978;38:4634-4639. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Vatanasapt V, Sriamporn S, Kamsa-ard S, Suwanrungruang K, Pengsaa P, Charoensiri DJ, Chaiyakum J, Pesee M. Cancer survival in Khon Kaen, Thailand. IARC Sci Publ. 1998;123-134. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. The impact of a decade long opisthorchiasis control program in northeastern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:551-557. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. Epidemiology of opisthorchiasis and national control program in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:327-332. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Macpherson CN. Human behaviour and the epidemiology of parasitic zoonoses. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1319-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |