INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC) is the primary cancer of the bile duct and is a frequent tumor of the biliary tree with estimated incidence of 0.01%-0.8 %[1,2]. Histologically, most CCCs are well differentiated adenocarcinomas, and classification based on location classically has been applied[3,4]. Intrahepatic CCC (IH-CCC) or peripheral CCC appears within the second bifurcation of hepatic bile duct, and is the second most common primary liver cancer following hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). IH-CCC or peripheral CCC often presents with advanced clinical features, and the cause for this cancer is still unclear. The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan has proposed a classification based on macroscopic features; CCC can be described as mass-forming, periductal infiltrating, intraductal growth, or as a mixed mass-forming, and periductal[5,6]. Tumors located in the left and right hepatic ducts and hilar cholangiocarcinoma were sometime classified as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma because these tumors can be very similar in condition to the periductal infiltrating type of CCC. However, hilar chlangiocarcinoma was eliminated from IH-CCC category. Periductal infiltrating type of IH-CCC and hilar cholangiocarcinoma demonstrate similar condition clinically. However, each substance has different epidemiological and pathological findings. Preoperative imagings, such as MRI, MRCP, CT, and FDG-PET, provide useful diagnostic informations in those patients.

Although surgical resection is the only chance for cure with result depending on exceptional surgical technique and patient selection, many patients, at the time of diagnosis, have IH-CCCs that are unresectable because of associated advanced liver disease or lesion involving the portal structure or main hepatic artery[7-9]. For these patients, liver transplantation provides the opportunity for better survival[10-14]. In case of inoperable patients, chemotherapy, radiation therapy or combination therapies remain as the only effective treatment[15,16].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, cholangiocarcinoma (IH-CCC and extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma) accounts for 3% of all gastrointestinal cancer and is the second most common primary malignancy[17]. Especially, IH-CCC accounts for approximately 10% to 20% of all primary liver cancer[18]. The incidence rates of IH-CCC are extensive, varying among different parts of the world. The incidence of IH-CCC appears to be higher among men in different areas of the world. The incidence ratios of male to female vary between 1.3 among white Americans to 3.3 among the French. In general, male preponderance is less pronounced in IH-CCC than in HCC. In Japan, IH-CCC accounts for about 5%-10% of all primary liver cancer[5], prevalence is slightly higher compared to that of Western countries and the United States. Furthermore, in most countries, the percentage of increase in IH-CCC mortality is higher than that of HCC. The 5-year patient survival of IH-CCC is still very low, and nearly unchanged over past 20 years.

RISK FACTORS

Several risk factors have been associated with the development of IH-CCC; however, the cause is still unknown for most IH-CCC cases. The association between IH-CCC and chronic biliary tract inflammation, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), liver fluke infestation, or hepatolithiasis, is well recognized. Especially, PSC is a definite risk factor for IH-CCC[19,20], and the risk for developing IH-CCC after the diagnosis of cholestatic liver disease is 1.5% per year[21]. Approximately 30% of the patients with PSC who are likely to develop IH-CCC will be diagnosed with malignancy of the bile duct within two years after diagnosis of the PSC[20,21]. Bile stenosis and recurrence of biliary inflammation might predispose individuals with these conditions to cancer.

TREATMENT

Treatment options for IH-CCC are determined by the local extent of the cancer, vascular invasion, presence or absence of metastasis, basic liver function, and available local expertise.

Surgical resection

Careful preoperative staging is required to determine the applicability of surgery with curative margin. Several factors influence the potency of surgery, and need to be carefully considered. These include the location and the extent of the tumor, and the patient’s conditions, such as liver cirrhosis, viral infection of the liver, cardiopulmonary diseases, jaundice, biliary tract infection, and ascites. Other factors, such as the patient’s performance status and nutritional condition, also require careful consideration. Routine imagings, such as ultrasonography, abdominal and chest computed tomography, and cholangiography [either magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatogram (MRCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram (ERC)], are useful for evaluating metastasis, tumor location, and extent of tumor. Angiography or 3-dimensional vascular imagings are helpful for evaluating vascular invasion.

Although surgical complete resection remains the only curative treatment strategy for IH-CCC, most patients present with advanced disease and cannot be applicable for surgical management. The selection of performable curative surgical resection depends on location of the tumors. Surgery for IH-CCC is similar to that of other liver malignancies, and includes hepatic lobectomy, segementectomy or subsegmentectomy with or without resection of the common bile duct. For hilar lesions, preoperative evaluation of tumor location and involvement of intra- or extra-hepatic biliary tree are extremely important for obtaining tumor-free margin. If the patient requires extended hepatic resection, preoperative portal vein embolization (PE) is effective for inducing lobar hypertrophy, and decreasing risk of operative modality and mortality, such as remnant liver failure[22]. In case with involvement of distal common bile duct, pancreato-duodenectomy is performed additionally to obtain negative margin.

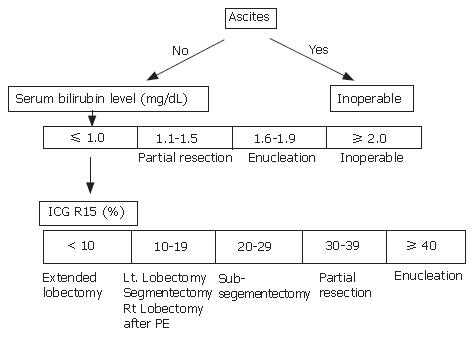

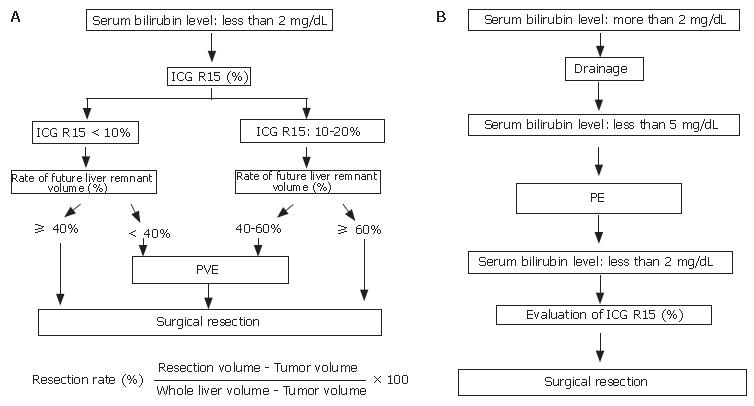

Some centers determined surgical resection and procedure according to Makuuchi criteria (Figure 1)[23]. If patients need extended hepatic resection, surgical strategy is indicated for patients with the total bilirubin level < 2 mg/dL prior to surgery. Indocyanine green (ICG) retention rate at 15 min is useful for evaluating liver function and determining surgical intervention. PE is employed for patients with normal liver function (ICG 15 ≤ 10%) when the future remnant liver volume is estimated to be less than 40% of the calculated total liver volume. For patients with mild liver dysfunction (10% < ICG 15 < 20%), PE is indicated when the remnant liver volume is estimated to be 40%-60% of the total liver volume (Figure 2A). In jaundiced patients, the intervention was performed after the serum total bilirubin level had decreased to less than 5 mg/dL. After total bilirubin level was decreased to less than 2 mg/dL, we calculated the patient’s ICG level, and surgery was performed (Figure 2B)[24-26].

Figure 1 Makuuchi craiteria.

Figure 2 Surgical management of IH-CCC.

In recent years, the outcomes after surgical resection have improved compared with the past results, though further advancements are necessary. Curative resection is associated with 5-year survival rate of up to 22%-36% for IH-CCC[27]. These low survival rates are considered to be due to the difficulty in identifying the extent of disease intra-operatively. Tumor-free surgical margin is the best predictor of patient survival. Bilobar distribution, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion and distant metastases were found to be poor predictors of survival rate of IH-CCC patients. In periductal infiltration type of IH-CCC, curative resection with lymph node dissection improved survival in patients with no more than two positive lymph nodes[28]. Shimada et al[29] reported that lymph node dissection did not appear to improve patient survival. Aggressive surgical approach with adjuvant chemotherapy may be effective in obtaining better patient survival rate. However, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with several modalities, including radiation, failed to demonstrate clear benefit[30].

Transplantation

The initial experience with liver transplantation (LT) for IH-CCC was unsatisfactory. Recurrence of IH-CCC was common and 5-year patient survival rate was only 5%-15%[12-14]. Most liver transplant centers consider IH-CCC as a contra-indication for LT[11-14]. Therefore, it is interesting to report that a selected group of patients who underwent LT and had negative surgical margin and no lymph nodes metastasis had long-term survival[14]. Prolonged disease-free survival was reported following LT for IH-CCC that combined preoperative radiation therapy and chemotherapy, and pre-transplantation exploratory laparotomy. These data support liver transplantation as an option for carefully selected patients with unresectable IH-CCC, but this should be offered only in the context of the clinical trial. It is also worth noting that these data have been originated from a single center with specialized interest in this disease; thus, general application of this experience remains to be validated.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy has been discouraging, and has not been convincingly shown to prolong survival and reduce tumor recurrence. It is worth noting that most studies of adjuvant therapy for IH-CCC patients have been small retrospective studies, and these are insufficient to reach statistically significant conclusions. Furthermore, the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy alone remains controversial, as it has been associated with improved survival in some studies, whereas no benefit in others[13,31,32].

Chemotherapy

The role of systemic chemotherapy in the unresectable IH-CCC is undefined. While no single agent or combination therapy has achieved significant response rates, most promising approaches involve the use of single agent gemcitabine (GEM). Combination regimens of GEM with agents, such as 5-FU, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and capecitabine, have been limited by toxicity without good effective response for unresectable IH-CCC patients[33]. The median survivals of 9.30 (range: 6.43-12.17) mo, 14 mo, and 11 mo were obtained by using the combination chemotherapy of gemcitabine with cisplatin[34], gemcitabine with capecitabine[35], and gemcitabine with docetaxel[36], respectively.

Radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy and chemotherapy have been administrated as adjuvant treatment to surgical resection. In the cases of complete resection, radiation did not improve survival[16]. Palliative radiation therapy might be suitable for patients with unresectable periductal infiltrating or intraductal growing types of CCC, with locally advanced lesion without distant metastasis. Palliative radiation therapy contributes to biliary decompression, and is pain-free. However, outcome of radiation therapy was also poor, with the patients’ survival of 3-6 mo, and without proven survival benefit over surgical resection[37].

OUR EXPERIENCE

From April 2000 to April 2006, a total of 756 cases with primary liver malignancies were treated at our department, among them 23 cases had IH-CCC. Data were collected retrospectively from all patient records and our database. When patients were not considered as candidates for surgical resection, chemotherapy or chemo-radiation therapies were indicated. The protocol administered consisted of GEM 400 mg/m2 with radiation therapy dose of 50 Gy, or GEM 800 mg/m2 alone. Patient follow-up was until the end of June 2006.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival rate was calculated using Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare survival. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

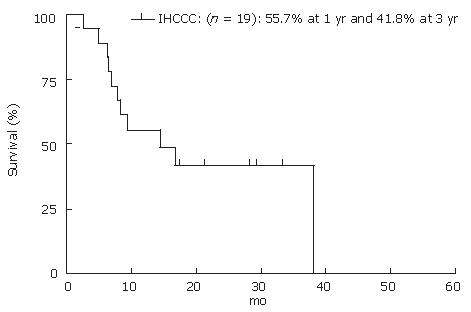

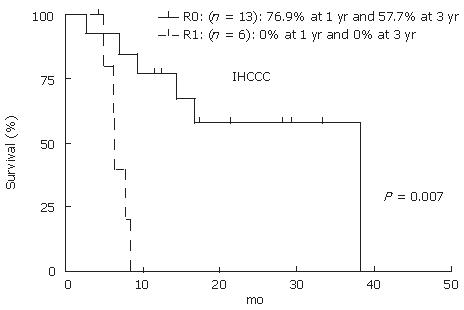

A total of 23 cases were found to have IH-CCC; of them, 19 cases (12 men and 7 women) were resectable, while 4 cases (2 men and 2 women) were unresectable. The mean age of patients was 62.1 ± 10.9 years. Out of 19 resectable cases, 14 had periductal infiltrating or intraductal growth-type tumor. Six cases underwent extended right lobectomy with the common bile duct resection (CBD-R) after PE. Three cases underwent extended left lobectomy with CBD-R, 2 cases underwent left lobectomy and posterior segmentectomy, respectively, and one underwent left trisegmentectomy with CBD-R following PE, and partial resection and extended lateral segementectomy. Eight of 19 patients were still alive at the end of the study. The actuarial patient survival at 1 and 3 years after resection was 55.7% and 41.8%, respectively (Figure 3). Fourteen of 19 patients had recurrence of CCC, most common recurrence site was remnant liver (10 of the 14 patients). Five patients had GEM treatment after recurrence; however, GEM did not have a significant effect on patient survival after recurrence (GEM: 11.4 ± 4.1 mo vs non-GEM: 15.3 ± 13.7 mo, P = 0.56). Thirteen of 19 (64.2%) cases received R0 resection by histological findings. Patient survival at 1 and 3 years for R0 cases were 76.9% and 57.7%, respectively. R0 resection had significant benefit on patients’ survival rate compared to R1 (Figure 4, P = 0.0007). GEM was administered to all four unresecteable cases for palliative treatment; however, mean survival time was 3.1 mo after treatment.

Figure 3 Actuarial patients survival calculated by using Kaplan-Meier methods at 1, 3 and 5 years after surgery for IH-CCC.

Figure 4 Actuarial patients survival calculated by using Kaplan-Meier methods at 1, 3 and 5 years after R0 versus R1 resection for IH-CCC.

In our study, the survival rate for the resected IH-CCC patients was still poor, which is similar with the previous reports. Thus, based on our data, it is considered that the effectiveness of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and palliative GEM treatment is still unclear.

SUMMARY

In view of increasing incidence of CCC, we need better methods of early detection, as well as new, effective treatment to improve the survival of the patients with this difficult disease. Surgical resection can be potentially curative, but many patients present at an advanced stage when resection might not be feasible. Chemotherapy and radiation are uniformly ineffective in prolonging survival.