Published online Jan 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.556

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 28, 2005

Published online: January 28, 2006

AIM: To determine whether body weight and/or serum leptin were independent predictors of response to antiviral treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

METHODS: A retrospective evaluation was performed in 139 patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon (IFN) from 1996 to 2000. Sustained response was defined as negative by hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA analysis using PCR and normal transaminase at 24 wk after cessation of IFN therapy. Patients who remained positive for HCV RNA at the end of IFN treatment were defined as resistant to IFN therapy. Sex, age, body mass index (BMI) (≥ 25 vs < 25), complication of diabetes mellitus, serum leptin level (≥ 8.0 μg/L vs < 8.0 μg/L), and the stage of liver fibrosis by needle biopsy (F1/F2 vs F3/F4) were examined.

RESULTS: Sustained response was achieved in 33 patients (23.7%), while others failed to show a response to IFN therapy. Overall, the factors associated with sustained antiviral effects were HCV-RNA load, HCV genotype, serum leptin level, and stage of liver fibrosis evaluated by univariate analysis. BMI was not associated with any therapeutic effect of IFN. Multivariate analysis indicated that HCV-RNA load was a significant risk factor, but among the patients with low viremia (HCV-RNA < 100 MU/L), leptin level was an independent risk factor for IFN resistance. Namely, a high level of serum leptin attenuated the effect of IFN on both male and female patients with low viremia.

CONCLUSION: High serum leptin level is a negative predictor of response to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C with low viremia.

- Citation: Eguchi Y, Mizuta T, Yasutake T, Hisatomi A, Iwakiri R, Ozaki I, Fujimoto K. High serum leptin is an independent risk factor for non-response patients with low viremia to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(4): 556-560

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i4/556.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.556

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) usually causes chronic infection, which can result in chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. Since interferon (IFN) therapy including pegylated interferon with ribavirin has been introduced, antiviral therapy is able to induce viral clearance and marked biochemical and histological improvements[2]. The response to IFN therapy varies among different viral (viral load and particularly genotype) and host factors, which may include race, sex, age, obesity, and presence of liver fibrosis. In Japan, around 70% of patients with chronic hepatitis C are infected with the HCV genotype 1b, and around 25% have genotype 2a. Sustained virological response to IFN monotherapy is as low as 10-20% in genotype 1b infections, whereas the response is more than 60% in genotype 2 infections until the combination therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin were presented[3,4]. However, it is not still possible to predict the response to IFN therapy in individual patients with each HCV genotype.

Obesity, a modifiable risk factor, may be an important cofactor in both accelerating fibrosis and increasing liver necroinflammatory activity in chronic hepatitis C[5]. Several studies have shown that obesity may also have a deleterious effect on the treatment response to both pegylated and standard IFN monotherapy[6,7]. Recent studies have indicated that food intake and body weight are regulated by leptin, of which synthesis is predominantly localized in adipose tissue[8]. The circulating leptin concentration correlates with fat mass size and distribution[9]. In addition to regulating food intake and energy expenditure, leptin has other metabolic effects on peripheral tissue, including modulation of action of insulin and in wound healing[10]. Activated rat hepatic stellate cells express leptin, and rat sinusoidal endothelial and Kupffer cells express the signaling-component isoform of the leptin receptor. Exposure of these cells to leptin results in an increased expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which, in turn, stimulates fibrogenesis in hepatic stellate cells[11]. Recent reports have indicated that inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α or IL-1, determine both leptin expression and circulation[12,13].

Judging from these results, besides viral factors, those related to individual patients including leptin and/or obesity might have important effects on IFN therapy. In this study, we have evaluated the risk factors that were related to resistance to IFN therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

One hundred and thirty-nine patients with chronic hepatitis C, who had received IFN monotherapy from 1996 to 2000 at Saga Medical School Hospital, were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: persistently elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels; positive for anti-HCV (third-generation enzyme immunoassay, Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA, USA); positive for HCV RNA qualitative analysis using PCR (nested polymerase chain reaction or Amplicor, Roche Diagnostic Systems, CA, USA); liver biopsy consistent with chronic hepatitis examined within 6 mo of enrolment; and naïve to IFN therapy. Exclusion criteria for treatment were as follows: nearly decompensated cirrhosis and/or HCC; positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (radioimmunoassay, Dainabot, Tokyo, Japan); autoimmune liver disease; hemochromatosis; Wilson’s disease; primary biliary cirrhosis; ingestion of more than 40 g/d of alcohol within the previous year; history of uncontrolled depression or psychosis; and patients with uncontrolled diabetes.

The data of patients’ sex, age, body mass index [BMI: weight (kg)/height (m2)], HCV genotype, HCV qualitative analysis with PCR, 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (75 g OGTT), serum leptin at initiation of treatment, and ethanol consumption were examined. Serum leptin was measured by a radioimmunoassay (RIA, Linco Research Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). Serum was collected at the initiation of treatment following an overnight fast for 8 h.

Liver biopsy specimens were obtained percutaneously or at peritoneoscopy using a modified Vim-Silverman needle. Liver biopsy specimens were reviewed by a single hepatologist, who was blinded to the clinical information of the subjects. For each liver biopsy specimen, hematoxylin-eosin and silver impregnation for collagen were available. Chronic hepatitis was diagnosed based on histopathological assessment according to a scoring system that includes semi-quantitative assessment of liver disease grading and staging[14]. Steatosis was evaluated by Adinolfi grading system in which steatosis is graded from 0 to 4 based on the percentage of hepatocytes involved as follows: 0 = none involved; 1 = up to 10%; 2 = up to 30%; 3 = up to 60%; and 4 = more than 60%[15].

In this protocol, 41 patients (29.5%) received IFN-β every day for 6 or 8 wk, and 98 patients (70.5%) received IFN-α for 24 wk (every day for 2 wk, followed by three times per week for 22 wk). A median total dose of IFN was 27 720 MU (range: 25 200-28 800 MU) in those treated with IFN-β and 62 500 MU (range: 46 800-78 000 MU) in those treated with IFN-α. Sustained response (SR) was defined as negative by HCV RNA qualitative analysis using PCR and normal ALT at 24 weeks after cessation of IFN therapy. Patients who remained positive for HCV RNA by PCR during and at the end of IFN treatment were defined as resistant to IFN therapy (non-response: NR). The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of Saga Medical School Hospital and informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Patients were divided into two groups: SR and NR. All were classified by age, sex, HCV RNA (low: < 100 MU/L; and high: ≥ 100 MU/L), viral serotype, alcohol intake, complication of diabetes (evaluated by 75 g OGTT), BMI (non-obese: < 25; obese: ≥ 25), leptin level (high: ≥ 8 μg/L; low: < 8 μg/L), and pathological findings of biopsy samples.

Comparisons between the two groups regarding these factors were performed using the χ2 test. Parameters that had an influence on IFN-response were compared by the univariate Cox’s proportional hazard model analysis. Variables that achieved statistical significance by univariate analysis were subsequently included in a multivariate proportional hazard model analysis. All analyses were carried out using SAS program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. Results were expressed as mean±SD unless otherwise stated.

Subjects included 87 men and 52 women. Mean BMI was 23.4 kg/m2, ranging from 16.9 to 33.6 kg/m2. Six percent of patients had an alcohol intake of more than 40 g/d. Ten subjects were complicated with diabetes mellitus. Seventy-one percent of patients were infected with HCV serotype 1, whereas 29% were infected with serotype 2. The subjects were divided into two groups using a cut-off viral load of 100 MU/L, and as a result, 50 subjects (16 women) showed a low viremia level (< 100 MU/L), and 89 (36 women) a high viremia level (>100 MU/L).

Liver histopathological examination revealed: 28 subjects with mild activity (A0 plus A1) and 111 with severe activity (A2 plus A3); 52 with mild fibrosis (F0 plus F1) and 87 with advanced fibrosis (F2 plus F3); 93 with mild steatosis (steatosis grade 1 plus 2) and 46 with severe steatosis (grade 3 plus 4). Mean serum leptin concentrations in all the subjects was 6.8 ± 5.5 μg/L, while high serum leptin concentrations beyond 8 μg/L were detected in 48 (34.5%) patients (Table 1).

| Total | NR | SR | P value | |

| (n = 139) | (n = 106) | (n = 33) | ||

| Age (yr) | 49.9 ± 11.1 | 70:30:00 | 25:06:00 | NS |

| Sex (male:female) | 87:54:00 | 62:44:00 | 25:08:00 | NS |

| HCV RNA load | 50:89 | 1.015972222 | 27:06:00 | < 0.0001 |

| (< 100 U/L:≥ 100 U/L) | ||||

| Serotype (1:2) | 99:40:00 | 81:25:00 | 18:15 | 0.026 |

| Alcohol intake (yes:no) | 0.424305556 | 0.319444444 | 2:31 | NS |

| Complication of | 0.50625 | 0.319444444 | 4:29 | NS |

| diabetes mellitus (yes:no) | ||||

| Body mass index (< 25:≥ 25) | 108:31:00 | 80:26:00 | 28:05:00 | NS |

| Leptin (< 8 μg/L:≥ 8 μg/L) | 91:48:00 | 63:43:00 | 25:03:00 | 0.017 |

| Pathological findings | ||||

| Grading (A0, A1:A2, A3) | 28:111 | 0.810416667 | 9:23 | NS |

| Staging (F0, F1:F2, F3) | 52:87 | 34:71 | 1 | 17:15 |

| Steatosis (grade 1, 2:3, 4) | 93:46:00 | 69:36:00 | 23:09 | NS |

SR was achieved by 33 patients (23.7%), while the remaining 106 patients (76.3%) failed to show a response. Comparison between the two groups evaluated by χ2 is shown in Table 1. Low viremia level was more frequent in patients with SR than in those with NR (P < 0.0001). In addition, HCV serotype was related to the response to IFN (P = 0.026). Subjects with low serum leptin levels (< 8 μg/L) were significantly associated with a good IFN-response (P = 0.017), whereas the low viremia group with a high serum leptin level (≥ 8 μg/L) achieved SR only in 12.5% of the subjects.

When subjects were classified into mild fibrosis (F0 + F1) and advanced fibrosis (F2 + F3), subjects with mild fibrosis were more likely to have a good response to IFN (P = 0.038). There was no significant difference of BMI or hepatic steatosis grade or leptin/BMI ratio (data not shown) between NR and SR. These factors were evaluated by univariate analysis and four possible risk factors that influenced the effect of IFN therapy on HCV virus were selected: serotype, HCV-RNA, liver fibrosis, and serum leptin level (data not shown).

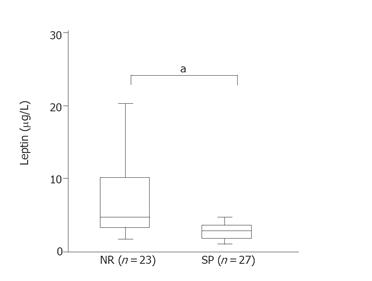

Multivariate analysis indicated that viremia level was the most significant factor among the four selected ones (Table 2). As a next step, we evaluated the data limited to the factors in the low viremia patients (n = 50). In patients with low viremia, only leptin level was an independent risk factor for IFN resistance (Table 2). This result regarding leptin level was supported by analysis using another statistical method (Figure 1), that is, evaluated by U-test. In patients with low viremia, leptin levels were significantly higher in the NR group compared to the SR group (P < 0.05).

| P | Odds ratio | RR (95%CI) | ||

| independently influenced SR (n = 33) | Serotype | 0.93 | 1.05 | (0.34-3.32) |

| HCV RNA | < 0.0001 | 12.74 | (4.15-39.08) | |

| Fibrosis | 0.18 | 0.49 | (0.18-1.39) | |

| Leptin level | 0.14 | 2.87 | (0.18-11.63) | |

| 50 subjects with low viremia level | Serotype | 0.95 | 0.25 | (0.25-3.63) |

| Fibrosis | 0.14 | 0.37 | (0.1-1.4) | |

| Leptin level | < 0.05 | 9.38 | (0.99-88.85) |

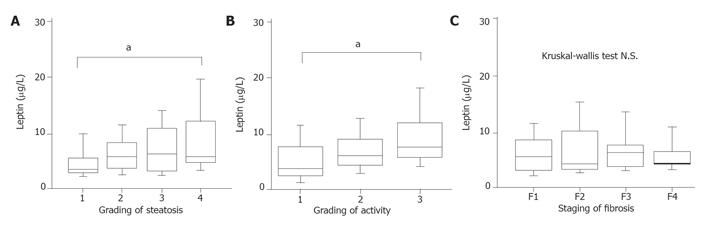

Although histopathological findings were not independent risk factors in multivariate analysis for IFN therapy, there were significant relations between the leptin level and activity grading + steatosis evaluated by Kruskal-Wallis test (Figures 2A and 2B). Evaluations using Kruskal-Wallis did not indicate a relationship between liver fibrosis and serum leptin level (Figure 2C).

This study demonstrated the possibility that among the host factors, serum leptin level can be a significant negative predictor for IFN-response in chronic hepatitis C. We evaluated 139 naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C who had received IFN monotherapy at our hospital. In this protocol, IFN-α or IFN-β was administered because intramuscular IFN-α and once-a-day intravenous IFN-β resulted in a similar sustained HCV RNA clearance in patients with chronic hepatitis C in Japan[16]. We showed the response rate and pretreatment predictive factors associated with IFN response in these patients. It was suggested that serum leptin level was an important factor for IFN response, although viral load was most critical for IFN therapy.

Overall, the SR rate in our study was 23.7% in patients receiving IFN monotherapy. Subjects with a low serum leptin level (< 8 μg/L) were significantly associated with a good IFN response. Multivariate analysis of all factors could not identify serum leptin level as an independent predictive factor associated with SR, because the high viral load markedly influenced on IFN therapy as has been indicated in several previous studies[17,18]. When evaluation was limited in the 50 patients with low viral load (< 100 MU/L), multivariate analysis revealed a significantly independent association between high serum leptin level and low IFN-response (OR = 9.38, P < 0.05). In this study, the relationship between BMI and serum leptin level was clearly seen, but not BMI alone, as an independent risk factor for IFN therapy. The reason for this discrepancy between leptin level and BMI was not ascertained in this study, but most Japanese obese subjects have a moderate BMI of around 25[19].

A histopathological approach indicated that serum leptin level was significantly associated with worsening steatosis and inflammatory activity, although these two factors in liver samples were not independent risk factors for IFN therapy in this study. Piche et al[20] reported that leptin is an independent metabolic factor associated with the severity of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C and higher BMI. Previous study demonstrated that overweight patients with chronic hepatitis C had significantly more steatosis and increased serum insulin and leptin levels[21]. On the other hand, Giannini et al[22] demonstrated that there was no relationship between serum leptin levels and the severity of steatosis, but their study design was different from this study. Namely, they excluded patients who had complicated diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and alcohol ingestion. The relationship between serum leptin levels and the severity of steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C remains controversial, because serum leptin levels can be affected by the progression of chronic hepatitis and host factors, such as visceral adiposity, insulin resistance and other adipokines. In this study, we could not demonstrate the relationship between liver fibrosis and serum leptin; the reason for this result might be explained by the fact that we enrolled naïve patients for IFN therapy in this study.

The mechanism of leptin in the antiviral response to IFN treatment was not determined in this study, but several studies might support the possibility of a relationship between the two factors. Serum leptin concentration increased in liver steatosis and cirrhosis in addition to obesity[23]. Another study also has shown that liver fibrosis correlates with steatosis and obesity[24]. From these studies, it could be judged that lipid deposits within the hepatocytes might cause functional disturbances by increasing the architectural distortion of the hepatic lobule caused by fibrosis, and decrease the contact area between drugs (e.g., IFN) and hepatocytes. While the expression of leptin in adipose tissue increased in response to feeding and energy repletion, leptin had a proinflammatory and/or profibrogenic role that might regulate cytokine-influenced repair and fibrogenesis of liver[11].

Our data suggests that low serum leptin might be a predictor for sustained viral response following a course of IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C with low viremia. In this study, we did not assess the difference of serum leptin levels in males and females because it was difficult to define normal ranges of serum leptin level in various stages of hepatic fibrosis and also the activity of leptin in each male and female patients are unclear. However, high serum leptin level is a remarkable risk factor for antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis C, because this study showed that serum leptin levels over 8 μg/L or less than 8 μg/L were able to be the threshold line for both males and females about the efficacy of antiviral therapy. This study does not address the issue if pretreatment intervention to decrease serum leptin level before IFN therapy would compensate for the low response rate in patients with a high serum leptin level. Prospective studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness of decreasing leptin level by interventions, such as weight reduction before IFN-therapy for enhancing antiviral responsiveness, and to investigate using combination therapy by peg-interferon and ribavirin.

S- Editor Kumar M, Pan BR and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349:825-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2159] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sobesky R, Mathurin P, Charlotte F, Moussalli J, Olivi M, Vidaud M, Ratziu V, Opolon P, Poynard T. Modeling the impact of interferon alfa treatment on liver fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C: a dynamic view. The Multivirc Group. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:378-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akuta N, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kumada H. Efficacy of interferon monotherapy to 394 consecutive naive cases infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 2a in Japan: therapy efficacy as consequence of tripartite interaction of viral, host and interferon treatment-related factors. J Hepatol. 2002;37:831-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kanai K, Kako M, Aikawa T, Kumada T, Kawasaki T, Hatahara T, Oka Y, Mizokami M, Sakai T, Iwata K. Clearance of serum hepatitis C virus RNA after interferon therapy in relation to virus genotype. Liver. 1995;15:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hourigan LF, Macdonald GA, Purdie D, Whitehall VH, Shorthouse C, Clouston A, Powell EE. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C correlates significantly with body mass index and steatosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1215-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lam NP, Pitrak D, Speralakis R, Lau AH, Wiley TE, Layden TJ. Effect of obesity on pharmacokinetics and biologic effect of interferon-alpha in hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:178-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bressler BL, Guindi M, Tomlinson G, Heathcote J. High body mass index is an independent risk factor for nonresponse to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:639-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9119] [Cited by in RCA: 8840] [Article Influence: 285.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Friedman JM. Leptin, leptin receptors and the control of body weight. Eur J Med Res. 1997;2:7-13. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ogawa Y, Masuzaki H, Hosoda K, Aizawa-Abe M, Suga J, Suda M, Ebihara K, Iwai H, Matsuoka N, Satoh N. Increased glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in transgenic skinny mice overexpressing leptin. Diabetes. 1999;48:1822-1829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ikejima K, Takei Y, Honda H, Hirose M, Yoshikawa M, Zhang YJ, Lang T, Fukuda T, Yamashina S, Kitamura T. Leptin receptor-mediated signaling regulates hepatic fibrogenesis and remodeling of extracellular matrix in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1399-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grunfeld C, Zhao C, Fuller J, Pollack A, Moser A, Friedman J, Feingold KR. Endotoxin and cytokines induce expression of leptin, the ob gene product, in hamsters. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2152-2157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zumbach MS, Boehme MW, Wahl P, Stremmel W, Ziegler R, Nawroth PP. Tumor necrosis factor increases serum leptin levels in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4080-4082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1582] [Cited by in RCA: 1504] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Ruggiero G. Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology. 2001;33:1358-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 773] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Furusyo N, Hayashi J, Ohmiya M, Sawayama Y, Kawakami Y, Ariyama I, Kinukawa N, Kashiwagi S. Differences between interferon-alpha and -beta treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:608-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, Boyer N, Poliquin M, Degott C, Descombes I, Le Breton V, Milotova V. Pretreatment serum hepatitis C virus RNA levels and hepatitis C virus genotype are the main and independent prognostic factors of sustained response to interferon alfa therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1995;22:1050-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shiratori Y, Kato N, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Hashimoto E, Hayashi N, Nakamura A, Asada M, Kuroda H, Tanaka N. Predictors of the efficacy of interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Tokyo-Chiba Hepatitis Research Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fujimoto K, Sakata T, Etou H, Fukagawa K, Ookuma K, Terada K, Kurata K. Charting of daily weight pattern reinforces maintenance of weight reduction in moderately obese patients. Am J Med Sci. 1992;303:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Piche T, Vandenbos F, Abakar-Mahamat A, Vanbiervliet G, Barjoan EM, Calle G, Giudicelli J, Ferrua B, Laffont C, Benzaken S. The severity of liver fibrosis is associated with high leptin levels in chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hickman IJ, Powell EE, Prins JB, Clouston AD, Ash S, Purdie DM, Jonsson JR. In overweight patients with chronic hepatitis C, circulating insulin is associated with hepatic fibrosis: implications for therapy. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1042-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Giannini E, Ceppa P, Botta F, Mastracci L, Romagnoli P, Comino I, Pasini A, Risso D, Lantieri PB, Icardi G. Leptin has no role in determining severity of steatosis and fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3211-3217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Testa R, Franceschini R, Giannini E, Cataldi A, Botta F, Fasoli A, Tenerelli P, Rolandi E, Barreca T. Serum leptin levels in patients with viral chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Purdie DM, Macdonald GA, Pandeya N, Shorthouse C, Powell EE. Steatosis and chronic hepatitis C: analysis of fibrosis and stellate cell activation. J Hepatol. 2001;34:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |