INTRODUCTION

Bile leakage is one of the major postoperative complications that may occur after hepatectomy. The reported incidence of postoperative bile leakage ranged from 4.8% to 7.6%[1-3]. Biliary complications including bile leakage after hepatic surgery are a major cause of morbidity and extended hospital stays. Lo et al[4] reported a high mortality rate in patients who required reoperation for biliary complication after liver resection. Biliary drainage is usually important and necessary for the treatment of bile leakage, but sometimes fails to improve bile leakage despite prolonged conservative drainage[5].

We report a case of postoperative refractory biliary leakage managed successfully by intrahepatic biliary ablation with ethanol.

CASE REPORT

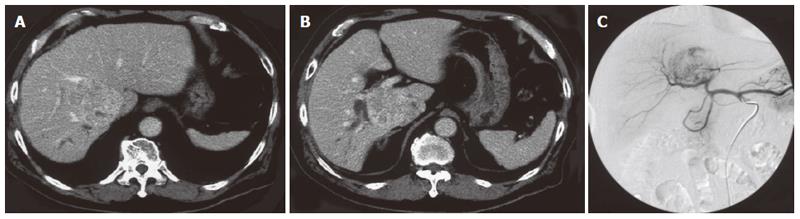

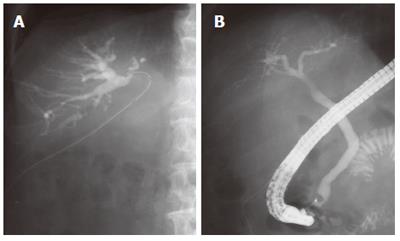

A 75-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a diagnosis of hepatic tumor. Abdominal computed tomography confirmed a 63 mm × 59 mm hepatic mass locating mainly in segment I with invasion into segment VI, VII, VIII, and V. This tumor obstructed the posterior branch of the bile duct, and oppressed the anterior branch of the bile duct, middle hepatic vein and infra vena cava (Figure 1A, B). Abdominal angiography revealed a hypervascular tumor in the right lobe at the early enhanced phase (Figure 1C). Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) was 227 ng/mL (normal, < 20) and 62 mAU/mL (normal, < 40), respectively. He had no additional underlying liver disease. We diagnosed him as hepatocellular carcinoma and decided upon surgery for radical treatment. An extended posterior segmentectomy including the caudate lobe and a part of the anterior segment was performed. Consistent with the findings of the preoperative computed tomography, the tumor was attached to the anterior branch of the bile duct, middle hepatic vein, and inferior vena cava, and was detached carefully from them and resected. During surgery, no particular problems were seen, including bile leakage. Postoperatively, the fluid from a drain locating in the resected liver surface contained total bilirubin (61.2 mg/dL), the volume of which was constant at 150 mL per day without decrease. This was thought to be caused by bile leakage. On d 32 after surgery, a fistulogram obtained from the drainage tube demonstrated a conduit between the anterior bile duct and fistula (Figure 2A). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography performed on d 39 after surgery demonstrated obstruction of the anterior bile duct (Figure 2B). Taken in sum, these examinations suggested a hole in the distal part of the anterior bile duct with its proximal obstruction. We tried to insert a biliary drainage tube into the anterior branch by percutaneous and endoscopic procedures to decrease the intraductal pressure and close the fistula, but failed. On d 46 after first surgery, a retrograde transhepatic biliary drainage (RTBD) tube was inserted into the anterior bile duct under open surgery. We waited to close the fistula in the outpatient follow-up, however a contrast study of the RTBD taken 7 mo post-surgery showed that the fistula remained patent. Because external biliary drainage continued despite prolonged conservative management, we decided to perform ethanol ablation of the isolated bile duct.

Figure 1 A, B: Abdominal computed tomography confirmed a 63 mm × 59 mm hepatic mass locating mainly in segment I with invasion into segment VI, VII, VIII, and V.

This tumor obstructed the posterior branch of the bile duct, and oppressed the anterior branch of the bile duct; C: Angiography revealed a hypervascular tumor in the right lobe at the early enhanced phase.

Figure 2 A: A fistulogram from the drainage tube demonstrated a connection between the anterior bile duct and fistula; B: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography showed obstruction of the anterior bile duct, and no connection between the common bile duct and the anterior bile duct.

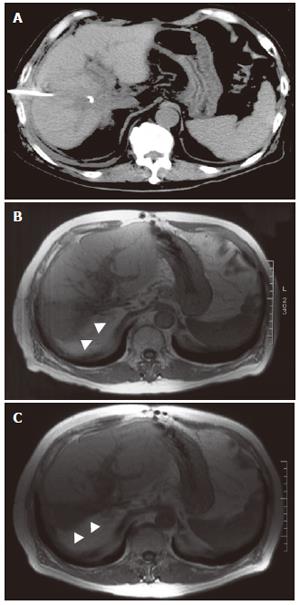

A 5 Fr balloon occlusion catheter was placed in the anterior bile duct through an RTBD tube. After the balloon was inflated to prevent leakage of the injected ethanol from the bile duct to the fistula, 4.0 mL pure ethanol was injected for ten minutes. Ethanol injection over 4.0 mL caused upper abdominal discomfort, so we decided that 4.0 mL was the appropriate volume. The ethanol injection was repeated five times a week. The volume of bile drainage was diminished to less than 100 mL after five injections, and the injections were continued thereafter. On the 23rd attempt, the volume of bile juice dropped to below 10 mL per day, and then the RTBD was clamped and removed two days later. Total bilirubin concentration of the drainage was also decreased from 61.2 mg/dL pre-injection to 6.9 mg/dL on the 11th attempt, and to 3.9 mg/dL on the 20th attempt. After RTBD removal, the patient had no complaints or symptoms. Compared with computed tomography taken before ethanol injection (Figure 3A), magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated atrophy of the ethanol-injected anterior segment without liver abscess formation (Figure 3B-C).

Figure 3 Follow-up computed tomography taken before ethanol injection (A), magnetic resonance imaging 3 mo (B) and 15 mo (C) after injection.

Arrows indicate the atrophy of the ethanol-injected anterior segment.

DISCUSSION

This report indicates that ethanol ablation may be effective in unfortunate cases of refractory biliary leakage after hepatectomy. However, this method can be performed in only biliary fistula without communication with the bile duct of the other remaining liver, because ethanol affects the remaining bile duct and causes irreversible damage. From this point of view, the reported case is thought to be one particularly suitable for ethanol biliary ablation.

Ethanol has been generally used as an injected agent percutaneously or angiographically for the treatment of various tumors because of its highly destructive properties, which lead to cell death by causing cell membrane lysis and protein denaturation[6]. Percutaneous transhepatic ethanol injection to the biliary tract has been reported. Controversy has surrounded chemical ablation of the gallbladder as an alternative to cholecystectomy for over a decade[7-11]. Recently, selective intrahepatic biliary ethanol injection as an alternative to preoperative portal vein embolization[12] or postoperative bile leakage[13] has been introduced. Kyokane et al reported that selective intrahepatic biliary ethanol injection destroyed the biliary epithelium, permeated parenchyma, induced hepatocyte denegeration, and resulted in compensatory hypertrophy of the non-injective hepatic lobe in an animal study. Compared with portal embolization, biliary ethanol injection was reported not to cause such severe side effects. In biliary ethanol injection, the hepatocyte denegeration with preservation of hepatic blood supply may prevent clinical liver necrosis or abscess[12]. Li et al[14] also demonstrated that biliary injection using phenol plus cyanoacrylate could achieve the effect of chemical hepatectomy.

Although this patient complained of abdominal pain during excessive ethanol ablation, this symptom was promptly relieved when the injection was stopped and the ethanol was removed from the bile duct via an RTBD tube. We were able to find the optimal injected ethanol dose through the patient’s complaint and fistulography, after which the patient did not complain of abdominal pain. In this method, the decision on the optimal injected dose may be important to prevent side effects[15].

Unfortunately, biliary leakage is sometimes encountered, and it can be complicated when it does occur[3,5,16]. Ethanol ablation of the bile duct provides a management option in cases in which conservative treatment has failed and a surgical approach is relatively difficult.