Published online Jun 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i21.3314

Revised: January 28, 2006

Accepted: March 13, 2006

Published online: June 7, 2006

The incidence of acute pancreatitis in Japan is increasing and ranges from 187 to 347 cases per million populations. Case fatality was 0.2% for mild to moderate, and 9.0% for severe acute pancreatitis in Japan in 2003. Experts in pancreatitis in Japan made this document focusing on the practical aspects in the early management of patients with acute pancreatitis. The correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and severity stratification should be made in all patients using the criteria for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and the multifactor scoring system proposed by the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas as early as possible. All patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis should be managed in the hospital. Monitoring of blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate, body temperature, hourly urinary volume, and blood oxygen saturation level is essential in the management of such patients. Early vigorous intravenous hydration is of foremost importance to stabilize circulatory dynamics. Adequate pain relief with opiates is also important. In severe acute pancreatitis, prophylactic intravenous administration of antibiotics at an early stage is recommended. Administration of protease inhibitors should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is confirmed. A combination of enteral feeding with parenteral nutrition from early stage is recommended if there are no clear signs and symptoms of ileus and gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis should be transferred to ICU as early as possible to perform special measures such as continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitors and antibiotics, and continuous hemodiafiltration. The Japanese Government covers medical care expense for severe acute pancreatitis as one of the projects of Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases.

- Citation: Otsuki M, Hirota M, Arata S, Koizumi M, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Takeda K, Mayumi T, Kitagawa M, Ito T, Inui K, Shimosegawa T, Tanaka S, Kataoka K, Saisho H, Okazaki K, Kuroda Y, Sawabu N, Takeyama Y, Pancreas TRCOIDOT. Consensus of primary care in acute pancreatitis in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(21): 3314-3323

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i21/3314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i21.3314

There are several guidelines for the treatment of acute pancreatitis, mostly based on published evidence[1-4]. If, however, there were no published evidence, data would not be adopted in guidelines even if the therapy is employed in clinical practice. There is little evidence for the treatment of acute pancreatitis in critically early stage, and thus it is not mentioned in the guidelines.

In July 2003, the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Pancreas Society and the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare published “Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Pancreatitis”[2,5]. The working party of the Research Committee of the Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas made the present document for the management of acute pancreatitis in the early stages after onset[6], which was not mentioned in the guidelines[2,5]. The management of patients with acute pancreatitis is complicated by an unpredictable outcome[7]. Many patients initially identified as having mild disease progress to severe disease indolently over the initial 48 h. This document is the consensus of experts in pancreatitis in Japan and focuses on the practical aspects in the early management of patients with acute pancreatitis and decisions needed within the first 48 h of care, introducing literatures on the treatment of acute pancreatitis published in Japanese.

This consensus guideline on acute pancreatitis is a review of literatures and experts’ opinions in Japan intended for general clinicians in primary care and emergency department, and gastroenterologists who do not have expertise in pancreatitis. However, this consensus by experts is only an example of standard practical medical care for patients with acute pancreatitis in Japan. Physicians need not necessarily follow this consensus but have to determine measures depending on hospital and patient specifics.

All patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis should be managed in the hospital. Monitoring of blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate, body temperature, hourly urinary volume, and blood oxygen saturation level (SpO2) by pulse oximetry is essential. Early vigorous intravenous hydration is of foremost importance. The correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and severity stratification should be made in all patients using the criteria for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and the multifactor scoring system proposed by the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas[8] as early as possible. Following the correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, severity stratification should be performed promptly and repeatedly after the onset, in particular for the first 48 h.

It is not possible to distinguish mild from severe acute pancreatitis during the early stages. Serum levels of amylase and lipase do not reflect the severity of acute pancreatitis[9,10]. Even patients who appeared to be mild acute pancreatitis at the first hospital visit (within 48 h after onset) often deteriorate. All patients with severe acute pancreatitis must be monitored closely for the development of organ failure and should be managed in, or referred to, an intensive care unit (ICU) with full monitoring and systems support. The mortality rate of patients with mild acute pancreatitis within the first 24 h who later showed exacerbation during 24-48 h was reported to be 11%[11].

When the diagnosis of severe acute pancreatitis was made, systemic administration of antibiotics and protease inhibitors, and special measures such as continuous regional arterial infusion (CRAI) of protease inhibitors and antibiotics, continuous hemodiafiltration (CHDF), and selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) should be considered.

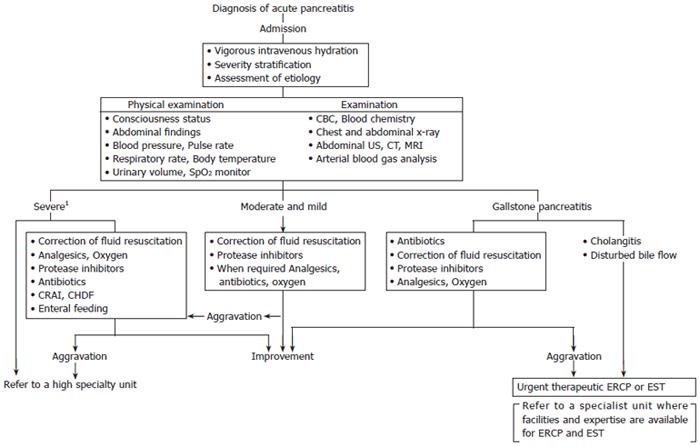

Patients with severe acute pancreatitis and those requiring interventional radiological, endoscopic, or surgical procedures should be managed in, or referred to, a specialty unit. Principles of management of acute pancreatitis are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Management | Physical check lists | Examination | Treatment |

| Within 24 h after onset | |||

| Initial vigorous intravenous hydration Severity stratification Assessment of etiology All patients with severe acute pancreatitis should be transferred to a high special unit or intensive therapy unit. | Consciouness status Abdominal findings Blood pressure Pulse rate Respiratory rate Body temperature Urinary volume Pulse oximetry (SpO2) | CBC and blood chemistry Chest and abdominal x-ray Abdominal US Abdominal CT and/or MRI Arterial blood gas analysis | Secure and maintain venous route Initial fluid resuscitation (60-160 mL/kg body weight/day) For the first 6 h, fluid resuscitation of about 1/2-1/3 of the amount required for the first 24 h Analgesics and oxygen, as required Protease inhibitors Antibiotics for severe cases and infection of the bile duct Consider CRAI CHDF in severe cases Urgent therapeutic ERCP or EST in patients with cholangitis or with disturbed bile flow (refer to a specialist unit where facilities and expertise are available for ERCP and EST) |

| From 24 to 48 h after onset | |||

| Re-evaluation of severity All patients with severe acute pancreatitis should be transferred to a high special unit or intensive therapy unit. | Consciouness status Abdominal findings Blood pressure Pulse rate Respiratory rate Body temperature Urinary volume Pulse oximetry (SpO2) | CBC and blood chemistry Chest and abdominal x-ray Arterial blood gas analysis Abdominal CE-CT, as required | Similar to the above-mentioned treatment In addition Correction of fluid resuscitation Enteral feeding in patients without clear signs and symptoms of ileus and gastrointestinal bleeding |

| After 48 h of onset | |||

| Fundamental conservative therapy in moderate and mildcases All patients with severe acute pancreatitis should be transferred to a high special unit or intensive therapy unit. | Consciouness status Abdominal findings Blood pressure Pulse rate Respiratory rate Body temperature Urinary volume Pulse oximetry (SpO2) | CBC and blood chemistry Chest and abdominal x-ray Arterial blood gas analysis Abdominal CE-CT, as required | Similar to the above-mentioned treatment In addition Correction of fluid resuscitation Enteral feeding in patients without clear signs and symptoms of ileus and gastrointestinal bleeding |

Acute pancreatitis should be diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis proposed by the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas[8]. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis are (1) acute abdominal pain and tenderness in the upper abdomen, (2) elevated pancreatic enzyme levels in blood, urine, or ascitic fluid, and (3) radiologic abnormalities characteristic of acute pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis can be diagnosed when two or more of the above criteria are fulfilled and other causes of acute abdominal pain are excluded. Acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis is included in acute pancreatitis.

The incidence of acute pancreatitis in Japan appears to be increasing[12] and ranges from 187 to 347 cases per million populations. Approximately 4.9% of patients who visited hospitals complaining of acute abdominal pain were found to have acute pancreatitis[13]. Thus, acute pancreatitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis for cases with signs and symptoms of digestive diseases. A history of the present illness and life-style, physical examination, blood tests such as amylase and lipase, and imaging studies such as abdominal plain X-ray, ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) should be undertaken to assist in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Therefore, every hospital that receives acute admissions should have facilities for acute pancreatitis to be diagnosed at any time. In addition, physicians should be aware of the presence of acute pancreatitis patients but without abdominal pain or signs and symptoms.

The initial treatment should be started as early as possible following the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

Following the correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, severity stratification should be performed promptly and repeatedly after the onset, in particular for the first 48 h. Severity of acute pancreatitis should be evaluated and scored by the multifactor scoring system proposed by the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas (JPN severity scoring system) (Table 2)[8]. We recognize that the Ranson, modified Glasgow, and APACHE II systems for evaluating acute pancreatitis are well established, but they might be outdated and are not used in Japan. Pathology-specific systems such as Ranson’s and the modified Glasgow require 48 h of data collection before the severity can be evaluated. JPN severity scoring system contains variables that represent different organ systems and can be consistently recorded at the time of admission to facilitate immediate management decisions.

| Prognostic factors | Clinical signs | Laboratory data |

| Prognostic factor I (2 points for each positive factor) | Shock | BE ≤ -3 mEq/L |

| Respiratory failure | Ht ≤ 30% (after hydration) | |

| Mental disturbance | BUN ≥ 40 mg/dL or | |

| Severe infection | creatinine ≥ 2.0 mg/dL | |

| Hemorrhagic diathesis | ||

| Prognostic factor II (1 point for each positive factor) | PaO2 ≤ 60 mmHg (room air) FBS ≥ 200 mg/dL Total protein ≤ 60 g/L LDH ≥ 700 IU/L Ca ≤ 7.5 mg/dL Prothrombin time ≥ 15 s Platelet count ≤ 1 × 105 /mm3 CT grade IV or V1 | |

| Prognostic factor III | SIRS score ≥ 3 (2 points) Age≥ 70 yr (1 point) |

When the correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is made, it should be considered to perform contrast-enhanced CT (CE-CT) and/or CE-magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI)[14-17], systemic administration of antibiotics[18] and protease inhibitors[19], and special measures such as CRAI of protease inhibitors and antibiotics[20,21], CHDF[22], and SDD[23]. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis and those requiring interventional radiological, endoscopic, or surgical procedures should be managed in, or referred to, a specialty unit.

There is no simple and reliable index to predict aggravation of acute pancreatitis in the early stages. Despite the importance of recognizing severe disease early in the course, many patients initially identified as having mild disease progress to severe disease indolently over the initial 48 h[11]. Severity stratification should be made repeatedly, particularly within the first 48 h after admission. Early recognition of severe disease and application of appropriate therapy require vigilance as decisions regarding management need to be made shortly after admission, often within the first 24 h.

Case fatality in acute pancreatitis in Japan in 2003 according to the JPN severity score was 0.2% (3/1223) with 0-1 point (Stage 0, 1), 3.7% (17/455) with 2-8 points (Stage 2), and 35.6% (32/90) more than 9 points (Stage 3, 4) (Table 3)[12].

The etiology of acute pancreatitis should be entertained early, especially in patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Although the vast majority of stones that cause acute pan-creatitis rapidly pass out of the common bile duct (CBD)[24], emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in selected patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis, who have evidence of biliary obstruction, cholangitis, and an elevated serum bilirubin levels within 24 h of admission, is reported to decrease the incidence of biliary sepsis[25]. Although abdominal US is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of cholelithiasis, it is not sensitive for the evaluation of choledocholithiasis in the setting of acute pancreatitis. Abdominal US can detect gallstones in the gallbladder in 60%-80% of cases, and in the bile duct in 25%-90% of cases of gallstone pancreatitis in the early stage[26]. Gallstones may be present in the CBD even in the absence of biliary ductal dilatation on abdominal US[27]. Laboratory testing may assist in the early identification of CBD stones. In patients with serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (or glutamic-pyruvic transaminase [GPT]) values greater than 150 IU/L at admission and without a history of high quantities of alcohol intake, gallstone pancreatitis cannot be denied even in the absence of bile duct dilatation[27,28]. Increasing serum levels of bilirubin or transaminases within 24-48 h of admission for acute pancreatitis predicts a persistent CBD stone[27]. It is reported that combination of abdominal US and laboratory parameters enables to diagnose gallstone pancreatitis with a sensitivity of 94.9% and a specificity of 100%[24]. When the diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis is in doubt, repeated imaging studies such as abdominal US, CT, MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)[29], or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)[30], together with serum biochemical tests such as ALT, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) and total bilirubin may provide good evidence for the presence or absence of gallstone pancreatitis[28].

Urgent therapeutic ERCP or EST should be performed in acute pancreatitis patients with suspected or proven gallstones[24,31,32]. All patients with severe acute gallstone pancreatitis should be managed in, or referred to, a specialist unit where facilities and expertise exist for ERCP at any time for CBD evaluation followed by EST and stone extraction or stenting, as required.

Although it is not clear how soon the full extent of the necrotic process occurs and only a quarter of acute pancreatitis patients develop necrosis, it is current practice in Japan to perform CE-CT on admission for severity stratification and correct evaluation of the range of poorly perfused area. A low-density area (poorly perfused area) on CE-CT suggests ischemic change with vasospasm or necrosis in and around the pancreas[33]. The presence of pancreatic necrosis and its range, infiltration of inflammatory changes are closely related with severity and prognosis[15,34]. In addition, CE-CT is required for the decisions on special measures such as CRAI of protease inhibitors and antibiotics, and CHDF. However, since anxieties persist over the potential for extension of necrosis and exacerbation of renal impairment following the use of intravenous contrast media[35,36], vigorous intravenous hydration for the purpose of intravascular resuscitation is important during and after CE-CT.

In severe cases, CT evidence of a low-density area suggesting ischemic change with vasospasm or necrosis in and around the pancreas, free intraperitoneal fluid and extensive peripancreatic fluid collection are observed since an early stage. Since the full extent of the necrotic process occurs at least 4 d after the onset of symptoms[16] and an early CT may therefore underestimate the final severity of the disease, it is desirable to perform CT on admission and repeated CT for reevaluation 2 or 3 d later.

Monitoring index: As the inflammatory process progresses early in the course of the disease, there is an extravasation of protein-rich intravascular fluid into the peritoneal cavity resulting in hemoconcentration. The reduced perfusion pressure into the pancreas leads to microcirculatory changes resulting in pancreatic necrosis[37]. At first, for appropriate fluid resuscitation, initial evaluation and monitoring of circulatory dynamics is important.

In all cases, status of consciousness, blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, body temperature, and hourly urinary volume should be monitored appropriately and chronologically.

The most important aim of fluid resuscitation is to stabilize circulatory dynamics, largely to keep the blood pressure and pulse rate at levels identical to those before onset of acute pancreatitis, and secure reasonable urinary volume. Since the urinary volume is closely related to appropriate circulatory plasma volume and blood pressure, maintenance of urinary volume is easy to monitor; 1 mL/kg body weight is the minimal hourly urinary volume that should be maintained.

In addition to the above-mentioned monitoring, cardio-thoracic ratio (CTR) by chest X-ray, blood gas analysis, serum electrolyte, and hematocrit should be determined to perform appropriate fluid resuscitation. Despite sufficient initial fluid resuscitation, aggravation of consciousness status, and the occurrence and progression of metabolic acidosis require re-examinations of other factors such as mesenteric ischemia and reevaluation of circulatory dynamics by determining central venous pressure (CVP) and monitoring pulmonary-artery catheter pressure. In cases of unstable circulatory dynamics, transfer to ICU with full monitoring and systems support should be considered.

Fluid resuscitation: (1) The amount of fluid resuscitation. Extravasation of protein-rich intravascular fluid into the peritoneal cavity early in the course of acute pancreatitis causes hemoconcentration and intravascular hypovolemia leading to impaired microcirculation in the pancreas. The decreased blood flow leads to stasis, thrombosis and subsequent pancreatic necrosis. Vigorous intravenous hydration can prevent the development of pancreatic necrosis. Fluid resuscitation for acute pancreatitis should be started by extracellular fluid such as acetate or lactate Ringer solution from a peripheral vein. Healthy adults require 1500-2000 mL fluid (30-40 mL/kg body weight), whereas patients with acute pancreatitis require 2-4 times (60-160 mL/kg body weight) the volume administered to healthy adults.

The severity of acute pancreatitis changes at every moment even if it appears to be mild on admission. Although acute pancreatitis typically results in significant intravascular losses, patients with acute pancreatitis are often given suboptimal fluid resuscitation. Since it is rare for the administration of large fluid volumes to be problematic in mild cases, aggravation by insufficient fluid resuscitation must be avoided. In particular, a large amount of fluid resuscitation (about 1/2-1/3 of the amount required for the first 24 h) is necessary in the first 6 h. Approximately 6 h after initiation of treatment, blood pressure, pulse rate, hourly urinary volume and the above-mentioned index must be re-evaluated to make plan for subsequent fluid resuscitation. In a mild case of acute pancreatitis, the amount and rate of fluid resuscitation should be reduced.

If shock or a pre-shock is present on arrival at the hospital, rapid intravenous fluid resuscitation of 500-1000 mL must be performed. Patients of 60 kg body weight with moderate to severe acute pancreatitis require about 1200-4800 mL fluid resuscitation for the first 6 h and 3600-9600 mL for the first 24 h. If the patient does not recover from circulatory failure by fluid resuscitation, administration of catecholamine and transfer to ICU with full monitoring and systems support should be considered.

We have reported that the average amount of fluid resuscitation on the first hospital day in patients who died of acute pancreatitis was 2788 ± 246 mL (n = 52, mean ± standard deviation) and that the amount of fluid resuscitation in 78.9% of these fatal cases for the first 24 h after admission was less than 3500 mL[38]. Indeed, all patients with inadequate fluid resuscitation (rehydration less than 4.0 liters) as evidenced by persistence of hemoconcentration at 24 h developed necrotizing pancreatitis[39].

The amount of fluid resuscitation required on the first and the following hospital day in moderate acute pancreatitis to maintain 120 mmHg or higher systolic blood pressure and hourly urinary volume of more than 1 mL/kg body weight was 4873 ± 2280 mL/d and 2000-2500 mL/d, respectively, while that in severe acute pancreatitis was 7787 ± 4211 mL/d and 4000-5000 mL/d, respectively[40]. Based on abdominal CT findings, Takeda et al[41] reported that the amount of fluid resuscitation on the first hospital day in patients with acute pancreatitis with inflammatory changes extending to anterior pararenal space, mesentery of the colon and the retroperitoneum beyond inferior pole of the kidney was approximately 4000 mL, 6000 mL, and 8000 mL, respectively. In some cases, body weight may increase more than 10 kg within a few days after onset of acute pancreatitis. It will take 1-2 wk for diuresis to occur resulting from re-filling to decrease body weight[41].

A large amount of fluid resuscitation is necessary until an adequate urinary volume is attained. Administration of diuretics before achievement of adequate fluid resuscitation may lead to a deterioration of the situation. Restriction of the amount of fluid resuscitation and excessive diuresis by diuretics because of fear of aggravation of pulmonary and systemic edema by a large amount of fluid resuscitation at this time may exacerbate the dysfunction of important organs including the kidney. Fluid resuscitation should be performed to promote prompt recovery from a potential shock state even if respiratory care under intratracheal intubation is required as a result of a large amount of fluid resuscitation. (2) Route of infusion. It is desirable to secure and keep the central venous route to maintain long-term fluid resuscitation and continuous infusion of protease inhibitors in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis, while the central venous route is redundant in mild cases. In severe acute pancreatitis, a central venous route should also be secured to monitor CVP chronologically and to determine the amount and rate of fluid resuscitation.

In the early stages of acute pancreatitis, vascular permeability often increases, and thus circulatory volume decreases resulting in a tendency for collapsed vascular lumen. Since access of the central vein is difficult in such cases, adequate levels of fluid should be given from a peripheral vein as the initial therapy. However, the femoral vein should be avoided if possible to prevent deep venous thrombosis and infection, and to securely obtain the route for CHDF and CRAI therapy. (3) Caution of fluid resuscitation. Since excessive amounts and a high rate of fluid resuscitation may cause pulmonary edema in patients with acute pancreatitis complicating heart, lung and renal dysfunction, and in elderly people, it is important to control the amount and rate of infusion according to the above-mentioned indexes such as blood pressure, pulse rate, urinary volume and CVP. However, it is thought that shock and aggravation of acute pancreatitis at an early stage tend to be due to insufficient amounts of the initial fluid resuscitation. It should be kept in mind to give adequate amount of fluid resuscitation at an early stage.

Serum levels of electrolyte and calcium should be measured and corrected appropriately, especially when tetany occurs due to low serum calcium concentrations.

There is no evidence to support the usefulness of administration of albumin preparation and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for primary care within 48 h of onset. Administration of colloid fluid at the acute stage may retard improvement of pulmonary edema in the re-filling period.

Analgesics: Since acute pancreatitis often causes extreme abdominal pain, which may disturb cardiopulmonary functions, adequate pain relief is required.

The following drugs should be given; buprenorphine (0.1-0.2 mg intramuscular or intravenous injection, or 0.3 mg/h intravenous drip infusion) or pentazocine (7.5-15 mg intramuscular or intravenous injection, or 15-30 mg intravenous drip infusion). Since there is a possibility that these drugs induce spasms of the sphincter of Oddi and disturb the outflow of bile and pancreatic juice when given frequently, administration of atropine sulphate in combination with analgesics is recommended. In addition, these analgesics must be given with caution, due to the risk of drug dependence when used continuously. However, neither buprenorphine nor pentazocine is approved by health insurance in Japan for pain of acute pancreatitis. Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection of pentazocine and buprenorphine is only approved for pain control of carcinoma and postoperative state, while intravenous injection of pentazocine is approved for anesthesia and buprenorphine for myocardial infarction and anesthesia.

A mixture of opium alkaloids and atropine (1.0 mL contains 20 mg opium alkaloid hydrochloride and 0.3 mg atropine sulphate, 1.0 mL subcutaneous injection), and a mixture of morphine and atropine (1.0 mL of this solution contains 10 mg morphine hydrochloride and 0.3 mg atropine sulphate, 1.0 mL subcutaneous injection) can also be given. Pain relief by epidural anesthesia is also possible in a high specialty unit. Since both reagents may cause respiratory depression, intensive monitoring of cardiopulmonary function is required after administration.

For mild pain in acute pancreatitis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac suppository and indomethacin suppository can be used. However, these agents should be used with caution due to associated adverse effects such as pernicious anemia, hemolytic anemia, granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, liver damage, acute renal failure, asthma, interstitial pneumonia, and peptic ulcer hemorrhage. These drugs are usually not used in moderate and severe cases of acute pancreatitis. In particular, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients in pre-shock status.

Antibiotics: In mild and moderate cases of acute pan-creatitis, prophylactic administration of antibiotics is unnecessary because the incidence of fatal infection of the pancreas and the exudates around the pancreas is low.

In severe acute pancreatitis, prophylactic intravenous administration of antibiotics at an early stage is reco-mmended[18,42,43]. Antibiotics with a broad antibacterial spectrum and good penetration into the pancreas[44] such as imipenem[18,42] and meropenem[43] are desirable. If infection of the biliary tract is suspected, administration of the second or later generation cephalosporins is also recommended. Clinicians should always take microbial substitution and fungal infection into consideration when using antibiotics.

The maximum dose of antibiotics that is approved by the Japanese Government should be used to attain sufficient concentrations in and around the pancreas. For example, intravenous infusion of 1-3 g/d imipenem or meropenem dividing into 3 times is recommended (1.0 g of imipenem or meropenem can be dissolved in 100 mL physiologic saline or 5% glucose solution, and infuse for more than 30 min). However, special attention has to be paid to the patient’s liver and renal function. In particular, in severe cases, it is necessary to re-evaluate the dose of antibiotics every day because liver and renal function changes chronologically day by day. If possible, it is recommended to monitor serum concentrations of antibiotics. Moreover, clinicians should be concerned about the possibility of developing fungal infections.

In cases with advanced inflammation in and around the pancreas, SDD is often undertaken to prevent bacterial translocation[23].

Protease inhibitors: Although the effect of protease inhibitors has some controversy, experts of pancreatitis in Japan recommend to administer protease inhibitors as soon as the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is con-firmed[19,45]. Recent meta-analysis of 10 articles of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effects of protease inhibitors for acute pancreatitis has revealed that treatment with protease inhibitors does not significantly reduce mortality in patients with mild acute pancreatitis, but may reduce mortality in patients with moderate to severe acute pancreatitis[46]. Table 4 shows examples of protease inhibitors used for acute pancreatitis in Japan[47].

| Mild and moderate | Severe | |

| Protease inhibitor | FOY | FOY + UTI |

| FUT | FUT + UTI | |

| UTI | ||

| Initial dose2 (during the first 12 h) | Maximum usual one- day dose1 by continuous intravenous infusion | Maximum usual one- day dose1 by continuous intravenous infusion |

| Until d 32 | Above dose for 24 h | Above dose for 24 h |

| First wk2 | Gradually reduce the above dose or intermittent administration | Above dose for 24 h |

| Second wk2 | Reduce the dose or cease | Maintain or gradually reduce the above dose |

| Third wk2 | Reduce the dose or cease | Maintain or gradually reduce the above dose |

Usual doses of gabexate mesilate (FOY), nafamostat mesilate (FUT) and ulinastatin (UTI) for acute pancreatitis are 200-600 mg/d, 10-60 mg/d and 50 000-150 000 units/d, respectively. However, since severe acute pancreatitis is often complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and shock, it is recommended that these reagents should be given in doses approved for these disorders in severe acute pancreatitis. The guidelines for acute pancreatitis in 1991 from the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas recommended combination therapy with FOY or FUT together with UTI when severe pancreatitis is predicted[47].

FOY and FUT have several adverse effects that clini-cians must be aware of; FUT increases serum potassium (K) concentration[48,49], and FUT and FOY may cause phlebitis, and inflammation, ulcer and necrosis of the skin with extravasation. In addition, there are reports of anaphylactic shock by repeated administration of FOY and FUT[50,51].

Enteral feeding: Based on the fact that enteral feeding stimulates pancreatic secretions[52], classical management recommends that patients presenting with acute pancreatitis be fasted until symptoms begin to resolve. However, there is no sufficient evidence to support the concept of gut rest (prohibiting enteral intake) in acute pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis results in hypermetabolic and hyperdynamic situation creating a high catabolic stress state[53]. Failure to achieve a positive nitrogen balance is associated with increased mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis[54]. Traditionally, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) has been advocated in these patients in order to supply adequate nutrients and prevent hypercatabolic states avoiding stimulation of exocrine pancreatic secretions. However, TPN in patients with acute pancreatitis has not been shown to be beneficial[55]. Early enteral nutrition through a nasojejunal tube is associated with a significantly lower incidence of infections, reduced surgical interventions, and a reduced hospitalization period compared with TPN[56]. Enteral nutrition is as safe and efficacious as TPN and may be beneficial during the clinical course of this disease. Even in severe acute pancreatitis, a combination of enteral feeding with parenteral nutrition from early stage is recommended if there are no clear signs and symptoms of ileus and gastrointestinal bleeding[58].

Although the majority of studies have reported enteral feeding via a nasojejunal tube, a recent pilot study of early nasogastric feeding in patients with severe acute pancreatitis proved that this approach might be feasible in up to 80% of cases[59]. However, caution should be used when administering nasogastric feeding to patients with impaired consciousness due to the risk of aspiration of refluxed feed.

Other treatments: Patients with acute pancreatitis often have deficiency of vitamin B1 due to alcohol abuse and malnutrition or abnormal and irregular dietary habits. Exacerbation of lactic acidosis or shock in such patients may suggest a deficiency of vitamin B1 and require corrective measures.

All patients when diagnosed with acute pancreatitis should be managed in a hospital. Patients with suspected acute pancreatitis should be examined at hospitals with facilities for blood examination and imaging studies. Depending on the severity, full monitoring and systemic support in high care unit (HCU) or ICU is necessary. Hospitals that cannot provide appropriate monitoring and adequate systemic support, should transfer all patients with severe acute pancreatitis to ICU as early as possible.

Evidence-based therapeutic guidelines for severe acute pancreatitis[2,5] published by the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japanese Pancreas Society and the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas recommends transferring acute pancreatitis patients with the JPN severity score 2 points or above[8]. Severe or aggravating cases should be transferred to ICU as early as possible to perform the CRAI of protease inhibitors and antibiotics or CHDF.

During transfer, cardiopulmonary function such as blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation must be monitored. In addition, a venous route must be secured by continuing fluid infusion to be able to cope promptly with a sudden change. In severe cases, a doctor and a nurse should accompany the patient during transfer.

Before deciding to transfer a patient, it should be considered about the influence of street transportation for long time on the patient’s clinical condition when vigorous fluid resuscitation is necessary at early period of illness.

Local core hospitals require facilities that can deal with severe acute pancreatitis.

To obtain high concentrations of protease inhibitors and antibiotics in the pancreas, these reagents are continuously infused into the artery through a catheter with tip placed at a portion where the bloodstream irrigates the inflamed area of the pancreas. Concentrations of protease inhibitors and antibiotics in pancreatic tissue after CRAI are approximately 5[60] and 5-10 times[61], respectively, higher than those after intravenous infusion. This procedure is therefore expected to directly inhibit inflammatory processes in the pancreas by strongly inhibiting activity of proteases that might aggravate pancreatic damage and inhibit most of the pathogens present in pancreatic infections[8,20,21,62]. Since protease inhibitors used in Japan also have anticoagulant and anticomplement activities (63), it is possible that these reagents inhibit the development of pancreatic necrosis by preventing the formation of microthrombi in pancreatic vessels and evolution of ischemia into pancreatic necrosis.

This procedure is indicated in severe acute pancreatitis cases with a low density area of the pancreas on CE-CT on admission, which corresponds with ischemic change and vasospasm on angiography or necrosis in and around the pancreas[33]. Takeda et al[21] have demonstrated that CRAI of protease inhibitors and antibiotics is effective in reducing mortality and preventing the development of pancreatic infection when initiated within 48 h after the onset of severe acute pancreatitis. FUT or FOY is used for this procedure, because these agents are synthetic low-molecular-weight protease inhibitors that inhibit a number of serine-proteases, and C1r and C1s esterases[63]. In addition, FOY and FUT might easily penetrate into the pancreatic acinar cells due to their low molecular weight and inhibit the inflammatory process in the pancreas. With regard to antibiotics, imipenem is used because of its broad spectrum and good penetration into pancreatic tissue[44]. Since CRAI of protease inhibitors and antibiotics for the treatment of acute pancreatitis is still debatable and not covered by health insurance in Japan, informed consent must be obtained from the patient before performing this procedure.

CHDF is a combination of continuous hemofiltration with hemodialysis developed as a continuous renal replacement therapy for patients with severe conditions. It is usually performed continuously for 24 h, and for 3-14 d. This procedure can be used to control fluid balance in patients with excessive fluid resuscitation but inadequate diuresis. However, in some hospitals this procedure is positively performed even if there is sufficient urinary volume, because CHDF can remove excess humoral mediators including cytokines during the hypercytokinemic state of systemic inflammatory response syndrome such as severe acute pancreatitis[22,64,65].

When this procedure is started early after onset of acute pancreatitis, reduction of chemical mediators and improvement of respiratory function is obvious, while the incidence of multiple organ failure is low compared to cases in which the procedure is initiated at a late stage[64]. Health insurance in Japan has approved CHDF as one of insurance-applicable treatment modalities for severe acute pancreatitis.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Toouli J, Brooke-Smith M, Bassi C, Carr-Locke D, Telford J, Freeny P, Imrie C, Tandon R. Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17 Suppl:S15-S39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mayumi T, Ura H, Arata S, Kitamura N, Kiriyama I, Shibuya K, Sekimoto M, Nago N, Hirota M, Yoshida M. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for acute pancreatitis: proposals. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:413-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pancreatic Disease Group, Chinese Society of Gastroenter-ology & Chinese Medical Association. Consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis. Chin J Dig Dis. 2005;6:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Pancreas Society, the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for acute pancreatitis. Tokyo: Kanehara 2003; . |

| 6. | Otsuki M, Hirota M, Arata S, Koizumi M, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Takeda K, Mayumi T, Kitagawa M, Ito T. Consensus of primary care in acute pancreatitis in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3314-3323. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Steinberg W, Tenner S. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1198-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Ogawa M, Hirota M, Hayakawa T, Matsuno S, Watanabe S, Atomi Y, Otsuki M, Kashima K, Koizumi M, Harada H. Development and use of a new staging system for severe acute pancreatitis based on a nationwide survey in Japan. Pancreas. 2002;25:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Lankisch PG, Burchard-Reckert S, Lehnick D. Underestimation of acute pancreatitis: patients with only a small increase in amylase/lipase levels can also have or develop severe acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1999;44:542-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yadav D, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1309-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Otsuki M, Itoh T, Koizumi M, Shimosegawa T. Deterioration factors of acute pancreatitis. Annual Report of the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. 2004;33-40 (In Japanese). |

| 12. | Kihara Y, Otsuki M, The Research Committee on Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2005;31:449 (Abstract). [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Otsuki M, Kihara Y. The incidence of acute pancreatitis in patients complaining of the abdominal pain. Annual Report of the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. 2003;21-25 (In Japanese). |

| 14. | London NJ, Neoptolemos JP, Lavelle J, Bailey I, James D. Serial computed tomography scanning in acute pancreatitis: a prospective study. Gut. 1989;30:397-403. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, Ranson JH. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology. 1990;174:331-336. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Isenmann R, Büchler M, Uhl W, Malfertheiner P, Martini M, Beger HG. Pancreatic necrosis: an early finding in severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1993;8:358-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, De Maertelaere V, Bali M, Winant C, Coppens E, Jeanmart J, Zalcman M, Van Gansbeke D, Devière J. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:715-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Vesentini S, Campedelli A. A randomized multicenter clinical trial of antibiotic prophylaxis of septic complications in acute necrotizing pancreatitis with imipenem. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:480-483. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Chen HM, Chen JC, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF. Prospective and randomized study of gabexate mesilate for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis with organ dysfunction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1147-1150. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Takeda K, Matsuno S, Sunamura M, Kakugawa Y. Continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitor and antibiotics in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1996;171:394-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Takeda K, Matsuno S, Ogawa M, Watanabe S, Atomi Y. Continuous regional arterial infusion (CRAI) therapy reduces the mortality rate of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: results of a cooperative survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:216-220. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moriguchi T, Hirasawa H, Oda S, Shiga H, Nakanishi K, Matsuda K, Nakamura M, Yokohari K, Hirano T, Hirayama Y. A patient with severe acute pancreatitis successfully treated with a new critical care procedure. Ther Apher. 2002;6:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Luiten EJ, Hop WC, Lange JF, Bruining HA. Controlled clinical trial of selective decontamination for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1995;222:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang SS, Lin XZ, Tsai YT, Lee SD, Pan HB, Chou YH, Su CH, Lee CH, Shiesh SC, Lin CY. Clinical significance of ultrasonography, computed tomography, and biochemical tests in the rapid diagnosis of gallstone-related pancreatitis: a prospective study. Pancreas. 1988;3:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, Lo CM, Zheng SS, Wong J. Early treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis by endoscopic papillotomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:228-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 542] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fogel EL, Sherman S. Acute biliary pancreatitis: when should the endoscopist intervene. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chang L, Lo SK, Stabile BE, Lewis RJ, de Virgilio C. Gallstone pancreatitis: a prospective study on the incidence of cholangitis and clinical predictors of retained common bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:527-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tenner S, Dubner H, Steinberg W. Predicting gallstone pancreatitis with laboratory parameters: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1863-1866. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Makary MA, Duncan MD, Harmon JW, Freeswick PD, Bender JS, Bohlman M, Magnuson TH. The role of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the management of patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:119-124. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Dahan P, Andant C, Lévy P, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, Dumont M, Erlinger S, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J, Zins M. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography and microscopic examination of duodenal bile in the diagnosis of cholecystolithiasis in 45 patients with normal conventional ultrasonography. Gut. 1996;38:277-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kaw M, Al-Antably Y, Kaw P. Management of gallstone pancreatitis: cholecystectomy or ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kozarek R. Role of ERCP in acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S231-S236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Takeda K, Mikami Y, Fukuyama S, Egawa S, Sunamura M, Ishibashi T, Sato A, Masamune A, Matsuno S. Pancreatic ischemia associated with vasospasm in the early phase of human acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:40-49. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Foitzik T, Bassi DG, Schmidt J, Lewandrowski KB, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Intravenous contrast medium accentuates the severity of acute necrotizing pancreatitis in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:207-214. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Carmona-Sánchez R, Uscanga L, Bezaury-Rivas P, Robles-Díaz G, Suazo-Barahona J, Vargas-Vorácková F. Potential harmful effect of iodinated intravenous contrast medium on the clinical course of mild acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1280-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fleszler F, Friedenberg F, Krevsky B, Friedel D, Braitman LE. Abdominal computed tomography prolongs length of stay and is frequently unnecessary in the evaluation of acute pancreatitis. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bassi D, Kollias N, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Foitzik T, Warshaw AL, Rattner DW. Impairment of pancreatic microcirculation correlates with the severity of acute experimental pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:257-263. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Otsuki M, Ito T, Koizumi M, Shimosegawa T. Mortality and deterioration factors of acute pancreatitis: the multicenter analysis of death from acute pancreatitis. Suizou. 2005;20:17-30 (In Japanese with English abstract). [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Brown A, Baillargeon JD, Hughes MD, Banks PA. Can fluid resuscitation prevent pancreatic necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:104-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kitano M, Yoshii H, Okusawa S, Kakefuda T, Nagashima A, Motegi M, Yamamoto S. [Hemodynamic changes in acute pancreatitis]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;94:824-831. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Takeda K. [Changes in the body fluid and fluid therapy in acute fulminant pancreatitis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;95:1-8. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Sharma VK, Howden CW. Prophylactic antibiotic administration reduces sepsis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2001;22:28-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Manes G, Rabitti PG, Menchise A, Riccio E, Balzano A, Uomo G. Prophylaxis with meropenem of septic complications in acute pancreatitis: a randomized, controlled trial versus imipenem. Pancreas. 2003;27:e79-e83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Büchler M, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, Isenmann R, Vanek E, Grimm H, Schlegel P, Friess T, Beger HG. Human pancreatic tissue concentration of bactericidal antibiotics. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1902-1908. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Harada H, Miyake H, Ochi K, Tanaka J, Kimura I. Clinical trial with a protease inhibitor gabexate mesilate in acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;9:75-79. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Seta T, Noguchi Y, Shimada T, Shikata S, Fukui T. Treatment of acute pancreatitis with protease inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1287-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Hayakawa T, Miyazaki I, Bannba T, Takeda Y, Kimura T. The guideline on application and dose of the enzyme inhibitor. The severe acute pancreatitis in Japan- Guide book of diagnosis and treatment. Tokyo: Kokusaitoshoshuppann 1991; 44-47. |

| 48. | Kitagawa H, Chang H, Fujita T. Hyperkalemia due to nafamostat mesylate. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Muto S, Imai M, Asano Y. Mechanisms of hyperkalemia caused by nafamostat mesilate. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26:1627-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Higuchi N, Yamazaki H, Kikuchi H, Gejyo F. Anaphylactoid reaction induced by a protease inhibitor, nafamostat mesilate, following nine administrations in a hemodialysis patient. Nephron. 2000;86:400-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Matsukawa Y, Nishinarita S, Sawada S, Horie T. Fatal cases of gabexate mesilate-induced anaphylaxis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 2002;22:81-83. [PubMed] |

| 52. | O'Keefe SJ, Lee RB, Anderson FP, Gennings C, Abou-Assi S, Clore J, Heuman D, Chey W. Physiological effects of enteral and parenteral feeding on pancreaticobiliary secretion in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G27-G36. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Dickerson RN, Vehe KL, Mullen JL, Feurer ID. Resting energy expenditure in patients with pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sitzmann JV, Steinborn PA, Zinner MJ, Cameron JL. Total parenteral nutrition and alternate energy substrates in treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:311-317. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Sax HC, Warner BW, Talamini MA, Hamilton FN, Bell RH Jr, Fischer JE, Bower RH. Early total parenteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: lack of beneficial effects. Am J Surg. 1987;153:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Meta-analysis of parenteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2004;328:1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gupta R, Patel K, Calder PC, Yaqoob P, Primrose JN, Johnson CD. A randomised clinical trial to assess the effect of total enteral and total parenteral nutritional support on metabolic, inflammatory and oxidative markers in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis (APACHE II > or =6). Pancreatology. 2003;3:406-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Meier R, Beglinger C, Layer P, Gullo L, Keim V, Laugier R, Friess H, Schweitzer M, Macfie J. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in acute pancreatitis. European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2002;21:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Eatock FC, Chong P, Menezes N, Murray L, McKay CJ, Carter CR, Imrie CW. A randomized study of early nasogastric versus nasojejunal feeding in severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kakugawa Y, Takeda K, Sunamura M, Kawaguchi S, Kobari M, Matsuno S. [Effect of continuous arterial infusion of protease inhibitor on experimental acute pancreatitis induced by closed duodenal loop obstruction]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;87:1444-1450. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Takagi K, Isaji S. Therapeutic efficacy of continuous arterial infusion of an antibiotic and a protease inhibitor via the superior mesenteric artery for acute pancreatitis in an animal model. Pancreas. 2000;21:279-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Imaizumi H, Kida M, Nishimaki H, Okuno J, Kataoka Y, Kida Y, Soma K, Saigenji K. Efficacy of continuous regional arterial infusion of a protease inhibitor and antibiotic for severe acute pancreatitis in patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Pancreas. 2004;28:369-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Fujii S, Hitomi Y. New synthetic inhibitors of C1r, C1 esterase, thrombin, plasmin, kallikrein and trypsin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;661:342-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Nakase H, Itani T, Mimura J, Kawasaki T, Komori H, Okazaki K, Chiba T. Successful treatment of severe acute pancreatitis by the combination therapy of continuous arterial infusion of a protease inhibitor and continuous hemofiltration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:944-945. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Oda S, Hirasawa H, Shiga H, Matsuda K, Nakamura M, Watanabe E, Moriguchi T. Management of intra-abdominal hypertension in patients with severe acute pancreatitis with continuous hemodiafiltration using a polymethyl methacrylate membrane hemofilter. Ther Apher Dial. 2005;9:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |