Published online May 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2770

Revised: November 1, 2005

Accepted: December 27, 2005

Published online: May 7, 2006

AIM: To study the association of colorectal serrated adenomas (SAs) with invasive carcinoma, local recurrence, synchronicity and metachronicity of lesions.

METHODS: A total of 4536 polyps from 1096 patients over an eight-year period (1987-1995) were retrospectively examined. Adenomas showing at least 50% of serrated architecture were called SAs by three reviewing pathologists.

RESULTS: Ninety-one (2%) of all polyps were called SAs, which were found in 46 patients. Invasive carcinomas were seen in 3 out of 46 (6.4%) patients, of whom one was a case of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). A male preponderance was noted and features of a mild degree of dysplasia were seen in majority (n=75, 83%) of serrated adenomas. Follow-up ranged 1-12 years with a mean time of 5.75 years. Recurrences of SAs were seen in 3 (6.4%) cases, synchronous SAs in 16 (34.8%) cases and metachronous SAs in 9 (19.6%) cases.

CONCLUSION: Invasive carcinoma arising in serrated adenoma is rare, accounting for 2 (4.3%) cases studied in this series.

- Citation: Chandra A, Sheikh AA, Cerar A, Talbot IC. Clinico-pathological aspects of colorectal serrated adenomas. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(17): 2770-2772

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i17/2770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2770

There has been a steadily increasing interest in serrated adenomas (SAs) of the colorectal mucosa since one of their earliest descriptions by Urbanski et al[1] in 1984 and later by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser in 1990[2]. As currently understood, SAs have characteristics combining those of hyperplastic polyps and adenomatous polyps. Architecturally, they resemble hyperplastic polyps with a characteristic “saw-toothed” or serrated morphology but their lining epithelium is dysplastic with varying grades of dysplasia (mild, moderate and severe) as seen in adenomatous polyps[3]. Earlier studies have focused on assessing not only their morphology[4-9] and progression[8-12] to carcinomas but also cytogenetic abnormalities which may occur within them[13-16]. This has given rise to the concept of a ‘serrated neoplasia pathway’ which refers to a pattern of progression of serrated adenomas to carcinomas[4]. The aim of this paper was to study the clinical significance of colorectal SAs with respect to their association with invasive carcinoma, local recurrence, synchronicity, and metachronicity.

An archival series of 4536 polyps spanning an 8-year period (1987-1995) were examined retrospectively. To date, this is the largest series of polyps evaluated for serrated adenomas. The adenomas were selected from the St Marks’s database using a computer search for cases which were diagnostically coded as ‘colorectal polyps’. The lesions represented polyps from a series of 1096 patients including endoscopically resected polyps and those from resected colons of patients undergoing surgery for carcinoma, FAP, inflammatory bowel disease or diverticular disease.

The slides (H & E staining) were reviewed by three pathologists (AC, AC & ICT) and all polyps were recorded as hyperplastic polyps, and tubular, tubulovillous, villous adenomas as well as invasive carcinoma. Degree of dysplasia of all polyps was also recorded as being mild, moderate or severe. The histologic diagnosis of serrated adenoma was based on the criteria described by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser[2]. In brief, histologic confirmation of a serrated glandular pattern simulating hyperplasia, the presence of goblet cell immaturity, upper crypt zone mitosis, and the prominence of nuclei were the criteria for inclusion. Adenomas showing at least 50% of these features were recorded as SAs. Case notes for patients with SAs were reviewed to record their age, sex, clinical presentation as well as the site, size, number of SAs and their clinical follow-up. All preceding and subsequent polyps were reviewed for the presence of synchronous and metachronous SAs, local recurrence and association with invasive carcinoma. Coexisting diseases were noted, including familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diverticular disease, family history of sporadic colorectal cancer and presence of other polyps. Unlike an earlier study[3], patients with known malignant potential (FAP, HNPCC) and inflammatory bowel disease were not excluded from this study as we wanted to draw attention to SAs arising in these conditions.

SAs were seen to comprise 2% of all polyps (n = 91) in this series involving 46 (4.2%) patients. Details of the different types of polyps encountered in this study are shown in Table 1.

| Types of adenoma | n (%) |

| Tubular adenoma | |

| Mild | 3582 (78.8) |

| Moderate | 114 (2.5) |

| Severe | 18 (0.4) |

| Tubulovillous adenomas | |

| Mild | 87 (1.9) |

| Moderate | 32 (0.7) |

| Severe | 5 (0.1) |

| Villous adenomas | |

| Mild | 5 (0.1) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) |

| Hyperplastic adenomas | 600 (13.5) |

| Serrated adenomas | 91 (2) |

| Invasive carcinoma | 14 (1.3) |

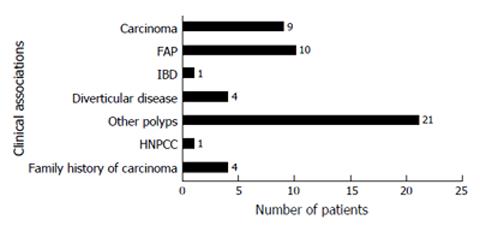

It was interesting to note that a significant proportion (n = 14, 15.4%) of SAs were originally reported as tubulovillous adenomas with the majority (n = 75, 83%) showing a mild degree of dysplasia. There was a male preponderance (70%), with the average age at diagnosis being 65.5 years for males and 67 years for females. The most common presenting complaint was bleeding per rectum. Clinical associations with other diseases in patients with SAs are shown in Figure 1. As seen in the figure presence of previous polyps, FAP and colorectal carcinoma were the conditions which are most frequently associated with SAs.

The most common site of occurrence was the rectum (33%) followed by sigmoid colon (20%). The size of the SAs was seen to vary between 0.1cm and 5.5 cm. The total number of synchronous SAs seen per patient varied between 1 (52%, n = 24) and 8 (2%, n = 1). Two SAs were seen in 8 (17%), 3 in 9 (20%) and 4 in 4 (9%) patients, respectively.

The mean time of follow-up was 5.75 years (range 1-12 years) with two patients being discharged from follow-up. Five patients died in the course of the follow-up of which 2 were from a FAP-related carcinoma and the remaining 3 were from unrelated causes.

Nine out of 46 (19.6%) patients with SAs had coexisting invasive carcinoma. In 3 (6.4%) cases, invasive carcinoma was seen to arise in SAs. Of these cases, 2 (4.3%) were sporadic and 1 (2.1%) was in a case of FAP. The remaining 6 (13.2%) carcinomas were presented discrete from SAs. The sporadic carcinoma in one of the above two patients was arising in a focus of severe dysplasia within SAs. The lesion was completely excised locally. There was also a synchronous SA in this patient. There was no recurrence at follow-up for 7 years in 2000. In the other patient, the invasive carcinoma arising in SAs was diagnosed in 1994. Local recurrences of invasive carcinoma were seen in 1995 and 1996 after which the patient was lost to follow-up.

All preceding and subsequent polyps retrieved from patients with SAs were reviewed with regard to metachronous SA and local recurrence. Twelve out of 46 (26%) cases showed either a recurrence or metachronicity. In 3 out of the 46 cases (6.5%) there was local recurrence, 2 of these within 1 year. In the remaining 9 cases of the 46 patients (19.6%) with SA, there were metachronous lesions seen. The time interval ranged 1-15 years with a mean time of 6.4 years and a median time of 6 years. Synchronous lesions were seen in 16 out of 46 patients (34.8%) with up to 5 synchronous lesions being present in one case.

Our interest in SAs was to evaluate clinically relevant information with respect to their association with invasive carcinoma, local recurrences and metachronicity. The prevalence of SA in our large random sample was 2% which is in the same range with other similar studies where the prevalence was noted to be 1.3%-7%[3,5-7,10] which is lower than 0.5% as originally quoted by Fenoglio-Preiser[2].

Recurrences of SA were seen in 3 cases (6.5%) and probably related to incomplete excision, as dysplastic epithelium was present at the margins of excision histologically. This is however lower than that for other colorectal polyps which are estimated to be 21%-41% with an average follow-up time of 5-10 years[17]. It must be borne in mind that the apparent difference in the recurrence rates may reflect the difference in the incidence of SA and other polyps. Interestingly, all 3 recurrences were associated with large rectal SAs (3.5 cm and 5 cm in diameter) and took place within 1 year. Synchronicity was noted in 34.8% (n = 16) of the cases which are comparable to 20%-61% seen with other adenomas[17] and metachronous SAs were seen in 9 cases (19.6%) which are lower than that quoted for other polyps (32%-55%)[17]. Nevertheless, it implies the real possibility of further SA present in a patient with a histologically confirmed SA. We found serrated adenomas in 10 cases of FAP, 4 cases of IBD and 1 of HNPCC. Though SA may be a feature of FAP, it is not characteristic of the attenuated phenotype with only a few cases being reported in the literature[18].

Progression of SA to frank carcinoma has been suggested in individual cases, but the prevalence of carcinoma originating from serrated adenomas and their cytogenetic characteristics are not fully understood[11,12]. There are a few immunohistochemical studies linking different genetic mutations and oncogene expression in SA[6,13-15], which may help to reinforce the concept of a “serrated neoplasia pathway”[4].

Inspite of the large number of polyps reviewed in our study, the number of cases in which sporadic cancers were seen to arise remains very small (2 out of 46, 4.3%). The prevalence of invasive carcinoma arising in SA in our study was lower than that in tubular adenomas (4.8%), tubulovillous adenomas (22.5%) and villous adenomas (40.7%) as reported in an earlier series from St Mark’s[17]. This prevalence (4.3%) shares some similarity to a large Finnish series which looked at specimens of 466 invasive colorectal carcinomas and found that 27 cases (5.8%) are associated with an adjacent SA[11].

In conclusion, the behaviour of carcinomas arising in SA cannot be reliably differentiated from those arising in other adenomas, given their small number in this series and further work both at identifying morphological features and genetic similarities to carcinomas is needed. SAs do not differ significantly from other adenomas with respect to patient demographics and synchronicity, however they have a lower but a definite incidence of metachronous lesions. Though the prevalence of invasive carcinoma arising in SA was lower than that in tubular, tubulovillous and villous adenomas in our study, further evaluation of this is needed, both of histological and of cytogenetic characteristics. It would be interesting to study SAs in other settings (IBD and polyposis) to shed further light on their behaviour particularly in view of growing evidence of a ‘serrated pathway’. The existence of such a distinct pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis has implication most notably for pathologists but at the same time for clinicians who need to recognise the entity of serrated adenomas and its associated potential for neoplastic progression.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Urbanski SJ, Kossakowska AE, Marcon N, Bruce WR. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps--an underdiagnosed entity. Report of a case of adenocarcinoma arising within a mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyp. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:551-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:524-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Matsumoto T, Mizuno M, Shimizu M, Manabe T, Iida M. Clinicopathological features of serrated adenoma of the colorectum: comparison with traditional adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:513-516. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hawkins NJ, Bariol C, Ward RL. The serrated neoplasia pathway. Pathology. 2002;34:548-555. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bariol C, Hawkins NJ, Turner JJ, Meagher AP, Williams DB, Ward RL. Histopathological and clinical evaluation of serrated adenomas of the colon and rectum. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yao T, Kouzuki T, Kajiwara M, Matsui N, Oya M, Tsuneyoshi M. 'Serrated' adenoma of the colorectum, with reference to its gastric differentiation and its malignant potential. J Pathol. 1999;187:511-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rubio CA. Colorectal adenomas: time for reappraisal. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:615-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torlakovic E, Snover DC. Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:748-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jaramillo E, Watanabe M, Rubio C, Slezak P. Small colorectal serrated adenomas: endoscopic findings. Endoscopy. 1997;29:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rubio CA, Nesi G, Messerini L, Zampi G. Serrated and microtubular colorectal adenomas in Italian patients. A 5-year survey. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1353-1359. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Makinen MJ, George SM, Jernvall P, Makela J, Vihko P, Karttunen TJ. Colorectal carcinoma associated with serrated adenoma--prevalence, histological features, and prognosis. J Pathol. 2001;193:286-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamauchi T, Watanabe M, Hasegawa H, Yamamoto S, Endo T, Kabeshima Y, Yorozuya K, Yamamoto K, Kitajima M. Serrated adenoma developing into advanced colon cancer in 2 years. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:467-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hiyama T, Yokozaki H, Shimamoto F, Haruma K, Yasui W, Kajiyama G, Tahara E. Frequent p53 gene mutations in serrated adenomas of the colorectum. J Pathol. 1998;186:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Jass JR, Yokota Y, Kobayashi M, Nishikura K. Infrequent K-ras codon 12 mutation in serrated adenomas of human colorectum. Gut. 1998;42:680-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kang M, Mitomi H, Sada M, Tokumitsu Y, Takahashi Y, Igarashi M, Katsumata T, Okayasu I. Ki-67, p53, and Bcl-2 expression of serrated adenomas of the colon. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fujishima N. Proliferative activity of mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyp/serrated adenoma in the large intestine, measured by PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen). J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jass JB, Price AB, Shepherd NA, Sloan JM, Talbot IC, Warren BF, Williams GT, Day DW. Morson and Dawson’s Gastrointestinal Pathology, 4th ed. Blackwell Sci Pub. 2003;551-609. |

| 18. | Gallagher MC, Phillips RK. Serrated adenomas in FAP. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2002;51:895-896; author reply 896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |