Published online Mar 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1403

Revised: August 20, 2004

Accepted: September 30, 2004

Published online: March 7, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the clinical presentations of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPT) and examine the diagnosis, treatment, low grade malignant potential of this rare disease.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed a series of seven patients with SPT managed in our hospital between July 1990 and October 2003. Six females and one male with mean age of 31 years (range 13 to 50 years) were diagnosed with SPT at our institution.

RESULTS: Clinical presentation included a palpable abdominal mass in two patients and vague abdominal discomfort in another two. Two patients were asymptomatic; their tumors were found incidentally on abdominal sonographic examination for other reasons. The final patient was admitted with hemoperitoneum secondary to tumor rupture. The mean diameter of the tumors in the seven patients was 10.5 cm (range 5 to 20 cm). The lesions were located in the body and tail in five cases and in the head of the pancreas in two. Surgical procedures included distal pancreatectomy (3), distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy (2), pancreaticoduodenectomy (1) and a pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure (1). There were gross adhesions or histological evidence of infiltration to the adjacent pancreas and/or splenic capsule in four cases. None of the patients received adjuvant therapy. The mean follow up was 7 years (range 0.5 to 14 years). One patient developed multiple liver metastases after 14 years of follow up.

CONCLUSION: SPT is a rare tumor that behaves less aggressively than other pancreatic tumor. However, in cases with local invasion, long-term follow up is advisable.

- Citation: Huang HL, Shih SC, Chang WH, Wang TE, Chen MJ, Chan YJ. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: Clinical experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(9): 1403-1409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i9/1403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1403

Most pancreatic tumors are malignant and have a bad prognosis. However, solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPT) is an unusual low-grade malignancy that rarely metastasizes[1]. Surgical resection is generally curative and the prognosis is excellent. We describe our experience with seven cases of SPT and review the literature.

Case 1 A previously healthy 13-year-old girl had noted an abdominal mass for 1 mo.

She denied any other symptoms or a family history of malignancy. On examination, there was a huge, firm, non-tender mass occupying nearly the entire abdomen. All blood tests were normal, including tumor markers. Abdominal ultrasound showed a large heterogeneous mass in region of the pancreatic tail. Abdominal CT scan disclosed a round, encapsulated mass of mixed density in the pancreatic tail that displaced the left kidney inferiorly and laterally. At operation, a large mass measuring 20 cm×17 cm with a smooth glistening surface was found attached to the underlying pancreas and spleen. As a well-defined margin could not be identified, a distal pancreatectomy was performed. Grossly the tumor weighed 2250 mg. The cut surface had a grayish white solid portion with intervening cystic spaces. Microscopically, it was compatible with SPT. Neither lymph node involvement nor capsular invasion was seen. No immunostains were performed. The patient was discharged on eighth postoperative day. There was no recurrence of the disease until 12 years later, although the patient was subsequently lost to follow up for 2 years. About 14 years after the initial surgery, she returned complaining of persistent abdominal discomfort with loss of appetite for 3 mo. Abdominal echo revealed multiple space-occupying lesions in the liver of varying size and mixed echogenicity. There was one hypoechoic lesion in the moderately enlarged spleen. Abdominal CT showed several well-defined mixed density lesions scattered in both lobes of the liver and one similar lesion in spleen, but there was no recurrence in the pancreas. Histologic examination of hepatic tissue obtained by an echo-guided biopsy revealed characteristics of SPT compatible with metastasis. The metastatic tumor cells were reactive for vimentin, α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin and NSE but not for chromogranin or synaptophysin. The patient underwent radiofrequency ablation therapy for palliative treatment but with no improvement. She died of progressive disease at 10 mo after the diagnosis of metastases.

Case 2 A previously healthy 19-year-old female presented with left upper abdominal pain following blunt abdominal trauma in a traffic accident. She was afebrile and initially had a normal pulse and blood pressure. There was a mild left abdominal tenderness on palpation. However, after 8 h of observation, she developed shock and signs of peritonitis. An abdominal CT showed a well-defined heterogeneous mass with a definite capsule. There was some soft tissue enhancement inside the tumor with contrast, and the capsule appeared to be disrupted. A substance with mixed echogenicity was coming from the mass and there was a fluid collection in the retroperitoneal space. The radiologist’s interpretation was a retroperitoneal tumor with internal bleeding. Laparotomy revealed a large, 8 cm×7 cm, well-encapsulated globular tumor arising from the tail of the pancreas. The abdominal cavity was filled with about 3000 mL of old blood clots. A distal pancreatectomy with complete excision of the tumor was performed. Histologically, the tumor had small uniform cells surrounding fibrovascular cores in a myxoid mucinous stroma. There was some papillary-like branching suggestive of SPT. The tumor extended into the surrounding pancreatic tissue although there was no definite perineural or vascular invasion. The tumor cells were reactive for α1-antitrypsin, NSE and vimentin, but not for cytokeratin, chromogranin or synaptophysin. The patient was well 6 mo after surgery.

Case 3 A 19-year-old female nursing student was admitted with an intra-abdominal mass that had been presented for 3 mo. She was incidentally found to have a vague mass when she and her classmates were practicing physical examination on each other. The mass was huge and firm, not totally mobile, and located in the middle of the abdomen. She did not immediately seek further evaluation because of the lack of other symptoms such as pain, abdominal fullness, fever, nausea, or vomiting. However, the mass gradually enlarged, and she lost three kilograms in the two months before admission. There was no history of hepato-biliary or pancreatic disease or other malignancy in her family. A complete hemogram and biochemistry tests, including liver function, were within normal limits. Tumor markers were also unremarkable. An abdominal echo revealed a large retroperitoneal tumor in the right upper quadrant compressing the right kidney. Abdominal CT showed a well-encapsulated lesion in the pancreatic head. Selective superior mesenteric artery angiography showed an avascular soft tissue lesion displacing near-by vessels. At surgery, a huge 10 cm×9 cm, lobulated mass was found arising from the pancreatic head and surrounded by multiple feeding vessels. Because of an irregular tumor margin with some adhesions around the tumor, malignancy was suspected, and a Whipple procedure was performed. The pathology showed fairly uniform oval to short cylindrical neoplastic epithelial cells growing in solid sheets with papillary structures and myxedematous stroma. The capsule was focally incomplete and perineural invasion was also seen. On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor was strongly positive for vimentin, α1-antitrypsin, and NSE and negative for chromogranin, estrogen and progesterone receptors. The patient was well without recurrent disease one year after the surgery.

Case 4 A 29-year-old woman with medically treated hyperthyroidism was admitted for a high fever and skin rash for 1 wk. Apart from a leucocytosis of 2.6×104/mm3 with a left shift, other routine laboratory tests were negative. An abdominal echo performed as part of a routine fever work up revealed a huge, well-circumscribed oval mass of mixed echogenicity in the tail of the pancreas. The patient denied alcohol drinking, smoking, or oral contraceptive pill use. There was no history of hospitalization for pancreatitis or trauma to the abdomen. CT scan of the abdomen showed a well-defined heterogeneous mass containing cystic and solid portions seeming to arise from the tail of the pancreas and displacing surrounding structures. The radiological diagnosis was a retroperitoneal tumor. At laparotomy, a huge 11 cm×8 cm tumor was found in the tail of the pancreas with extension to the splenic hilum. A distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy were performed. Histologically, the tumor was composed of nests of epithelial cells with a solid pseudopapillary, cystic and trabecular pattern suggestive of SPT. Immunostaining was positive for NSE, α1-antichym-otrypsin, chromogranin, cytokeratin and vimentin. Some tumor cells extended to the peri-splenic soft tissue and adhered to the capsule of the spleen. The patient had no evidence of recurrence after 3-years’ follow up.

Case 5 A 42-year-old women with mild hypertension developed persistent left upper abdominal discomfort for 3 mo. There was no anorexia, vomiting, or fever. She denied any change in bowel habits or weight loss. She appeared to be well developed and well nourished. On abdominal examination, there was a huge mass in the left upper quadrant that was mildly tender to palpation. Abdominal sonography revealed a well-defined retroperitoneal mass with a cystic appearance. All routine laboratory tests, urinalysis, and a test for occult blood in the stool were all normal, as were CEA and CA-199. CT scan showed a large well circumscribed mass in the body and tail of the pancreas. There was a irregular wall enhancement on contrast injection and calcified densities in the lower portion of the lesion. It was interpreted as a retroperitoneal tumor. Exploratory laparotomy showed a large tumor measuring 15 cm in diameter arising from the body and tail of the pancreas. It adhered extensively to the distal pancreas and spleen, requiring distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Pathologically, the tumor cells were small and uniform with a finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and rare mitoses. They grew in solid sheets or papillary projections compatible with SPT. No immunostains were performed. The patient has had no recurrence or metastasis after 14 years.

Case 6 A 45-year-old female was admitted because of sonographic evidence of pancreatic tumor found during a routine medical check. Apart from frequent abdominal fullness, there were no other gastrointestinal symptoms. Tumor markers and other laboratory tests were within normal limits. Repeat abdominal echo revealed a hyperechoic mass in the body of the pancreas. CT scan showed an ill-defined heterogeneous solid mass with moderate enhancement in the pancreatic body measuring about 5 cm×4 cm. Tiny calcifications were present within the lesion. There was no dilatation of the pancreatic or bile duct. At surgery, the tumor was enucleated and a distal pancreatectomy was performed. Histologically, the tumor showed characteristics of SPT. Tumor cells were positive for vimentin, NSE and α1- antitrypsin, but not for endocrine markers including chromogranin and synaptophysin. At the 2-year follow up, there was no recurrence of the disease.

Case 7 A 50-year-old previously healthy man was transferred to our hospital for a suspected tumor in the pancreatic head. He had had persistent epigastric discomfort before meals for 1 year but no nausea or vomiting. He denied weight loss or poor appetite. Physical examination was unremarkable. Abdominal sonography revealed a heterogeneous mass with a central hypoechoic component in the head of the pancreas measuring about 5 cm×4 cm. On abdominal CT, the tumor was located in the superior aspect of the pancreatic head and had relatively low attenuation. It was thought to be pancreatic carcinoma. Neuroendocrine markers, CEA, and CA-199 were not elevated. At laparotomy, an oval well-encapsulated lesion slightly adherent to the adjacent pancreatic tissue was found, and a pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed. Microscopically, the tumor cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm with monomorphic round to oval nuclei in a delicate fibrovascular stroma. Some cells were arranged in large branching papillary clusters with slender central fibrovascular cores. The tumor cells were strongly positive for vimentin, α1-antitrypsin, cytokeratin, and NSE but not for chromogranin or synaptophysin. Although there were several foci of perivascular invasion and infiltration of tumor cells into the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma, the patient remained well after 6 years of follow up.

Demographic and clinicopathological findings of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Only one was male. The mean age was 31 years (range 13 to 50 years).Two patients presented with a palpable abdominal mass and two others with abdominal discomfort. Another two patients were asymptomatic, with tumors found incidentally during sonographic examination for other reasons. One patient was admitted with hemoperitoneum from a ruptured tumor after blunt abdominal trauma.

| Case | Age (yr) | Sex | Presentation | Site | Size (cm) | Local Invasion/metastasis | Operation | Follow up (yr) |

| 1 | 13 | F | Mass | Tail | 20 | Liver and Spleen | DP | REC (14) |

| 2 | 19 | F | Hemoperi- toneum | Tail | 8 | Pancreas | DP | AW (0.5) |

| 3 | 19 | F | Mass | Head | 10 | Pancreas | Whipple | AW (1) |

| 4 | 29 | F | Asympto- matic | Tail | 11 | Spleen | DP+S | AW (3) |

| 5 | 42 | F | Abdominal discomfort | Body + Tail | 15 | Pancreas and spleen | DP + S | AW (14) |

| 6 | 45 | F | Asympto-matic | Body | 5 | Nil | DP | AW (2) |

| 7 | 50 | M | Abdominal discomfort | Head | 5 | Pancreas | PD | AW (6) |

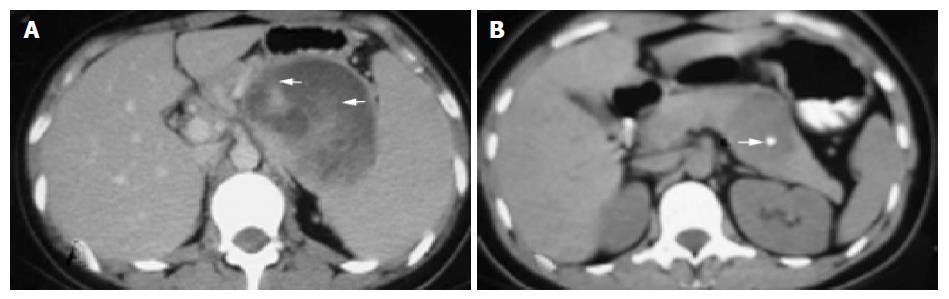

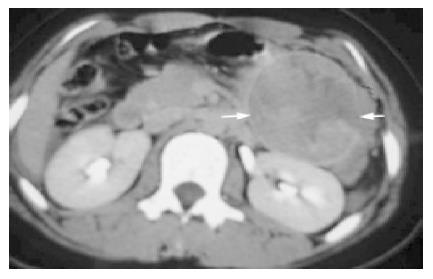

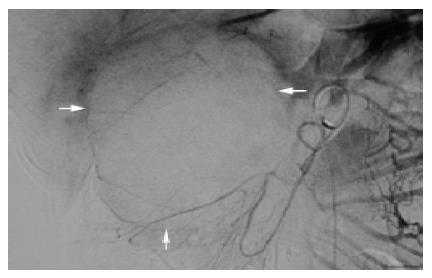

The sonographic features were similar in all cases, with relatively large tumors with mixed echogenicity in or adjacent to the pancreas. The CT scans revealed large well-encapsulated and circumscribed retroperitoneal masses with central heterogenicity and displacement of nearby structures. Other more variable radiologic features included intravenous contrast enhancement suggesting hemorrhage (Figure 1A) in cases 1 to 5 and calcifications in or at the periphery of the mass (Figure 1B) in cases 5 and 6. Five tumors were located in the body and tail and two in the head of the pancreas. In the case of traumatic rupture, there was disruption of the capsule and retroperitoneal hemorrhage (Figure 2) in case 2. Angiography was performed only in case 3 and showed an avascular tumor with displacement of the surrounding vessels (Figure 3).

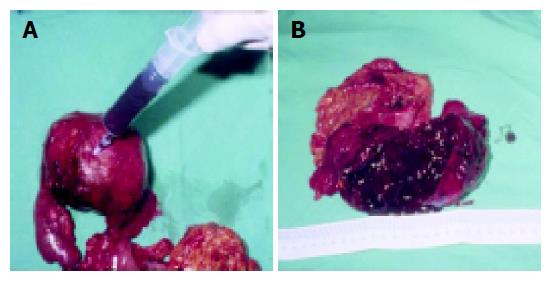

The mean tumor diameter was 10.5 cm (range 5 to 20 cm) and all tumors have a definite fibrotic capsule. Most had hemorrhagic degeneration and old blood clot could be aspirated from the cystic part of the mass (Figure 4A). Cut sections of the tumors showed multiple cystic spaces, and some were filled with old blood clots interspersed with solid gray white areas, depending on the degree of necrosis (Figure 4B). The proportion of cystic to solid areas was very variable. In five cases (1, 3, 4, 5, and 7), the tumors were adherent to the adjacent pancreas and spleen, requiring more aggressive surgery, such as distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or a Whipple procedure.

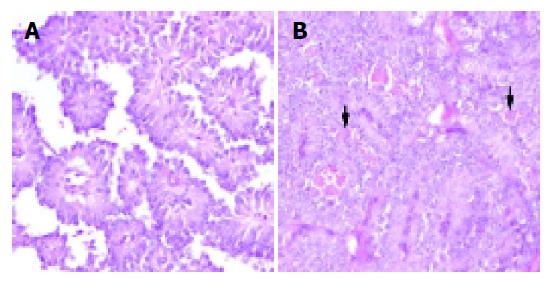

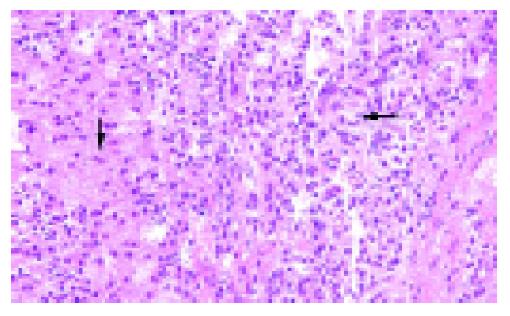

Histologic examination of the tumors showed cystic, solid and pseudo-papillary structures (Figure 5). In the papillary areas, the tumor cells were uniform, short, and cylindrical with monomorphic round to oval nuclei and rare mitoses (Figure 6A). In the solid areas (Figure 6B), similar tumor cells, some with cytoplasmic hyaline globules were found. In cases 3 and 7, there were microscopic invasion nerves or vessels, and the capsule was incomplete. Infiltration of tumor cells through the capsule into the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma, the spleen, or both were noted in cases 2, 4, and 7.

Immunohistochemical studies were performed in six cases (primary tumor in cases 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 and liver metastases in case 1) (Table 2). They were mostly strongly positive for vimentin, α1-antitrypsin, NSE, and negative for chromogranin and synaptophysin. α1-antichymotrypsin was positive in metastatic lesion of case 1 and primary lesion of case 4. Also case 4 and 7 reactive for cytokeratin. Estrogen and progesterone receptors were tested in only case 3 and they were found to be absent.

| Case | Lesion | AAT | ACT | NSE | Vim | CTK | Chr | SYN | Est | Pro |

| 1 | M | Posi | Posi | Posi | Posi | - | Neg | Neg | - | - |

| 2 | P | Posi | - | Posi | Posi | Neg | Neg | Neg | - | - |

| 3 | P | Posi | - | Posi | Posi | - | Neg | - | Neg | Neg |

| 4 | P | - | Posi | Posi | Posi | Posi | Posi | - | - | - |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | P | Posi | - | Posi | Posi | - | Neg | Neg | - | - |

| 7 | P | Posi | - | Posi | Posi | Posi | Neg | Neg | - | - |

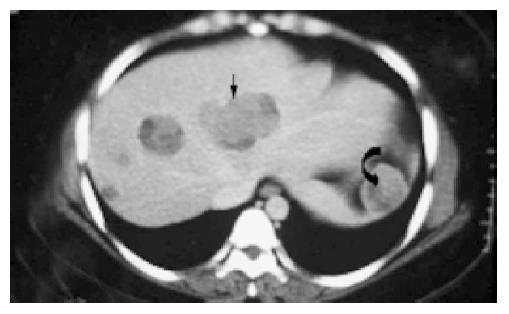

After surgery, the patients were apparently disease-free without adjuvant therapy on follow up ranging from 0.5 to 14 years (mean 7 years). However, in case 1, metastases were found in the liver and spleen 14 years after surgery (Figure 7), ultimately leading to the patient’s death. The histological features of the hepatic metastases (Figure 8) were identical to those of the primary tumor.

Pancreatic tumors can be divided into three categories: exocrine tumors arising from acinar and ductal cells, endocrine tumors, and rare mesenchymal neoplasms. Pancreatic tumors are relatively less common that certain other malignancies, but they generally have an extremely poor prognosis. SPT is a very rare entity, with a reported incidence of 0.13% to 2.7% of all pancreatic tumors[2]. Although its cause is still unknown, the pathological features are better understood.

SPT was first described by Frantz in 1959[3]. Since then, various names have been used to describe this unusual lesion, such as solid and cystic tumor of the pancreas, papillary-cystic tumor, solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm, and SPT of the pancreas. The last is the most recently accepted term (WHO, 1996)[4].

Mao[5] in a cumulative review of the literature, found that 90% of patients were females with a mean age of 23.9 years, slightly younger than the mean in our series (31 years). The male:female ratio is 1:9.5[5]. It has a low-grade malignant potential. It tends to be fairly benign in young females but appears to be more aggressive in older males, whose mean age is about 10 years older than women [6,16]. In our series, there was only one male patient, and he was the oldest.

Clinically, patients with SPT of the pancreas usually have vague abdominal symptoms with fullness or discomfort, pain, and a palpable abdominal mass. About 9% of patients are reportedly asymptomatic[2]. Rupture of a large tumor with intra-abdominal hemorrhage as occurred in our second case is uncommon but has been previously documented by Mao[5].

Physical examination is often normal apart from the presence of an upper abdominal mass. Usually there is no evidence of pancreatic insufficiency, abnormal liver function tests, cholestasis, elevated pancreatic enzymes, or an endocrine syndrome. Tumor markers are also unremarkable. Given the good prognosis of the disease, it’s important to make the diagnosis preoperatively if possible so that adequate resection will be undertaken. Therefore, imaging studies should be carefully assessed, with FNAC considered if necessary[2]. Abdominal ultrasound and CT show a well-encapsulated, complex mass with both solid and cystic components and displacement of nearby structures. There may be calcifications at the periphery of the mass and intravenous contrast enhancement inside the mass suggesting hemorrhagic necrosis[1]. Procacci et al reported the accuracy of CT scan in diagnosing cystic pancreatic masses to be about 60%[7]. According to Cantisani et al. MRI is better than CT for distinguishing certain tissue characteristics, such as hemorrhage, cystic degeneration, or the presence of a capsule, particularly as indicated by high signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and slightly progressive heterogeneous peripheral contrast enhancement, seen after godolinium administration on dynamic examination[8]. Angiography usually demonstrates an avascular or hypovascular pancreatic tumor and may help delineate the mass from other involved and adjacent structures[2].

Although, some radiological signs are suggestive of SPT, radiologically guide FNAC may be needed to obtain a preoperative diagnosis. In one study reviewing over 150 cases of SPT, when preoperative FNAC was done, over 70% of lesions were definitly diagnosed as SPT or had SPT or low-grade epithelial neoplasm in the differential diagnosis[2].

The origin of this tumor remains an enigma. Kosmahl[9] attempted to correlate the immunoprofile of tumors in 59 patients with a cellular origin for SPT. They used a number of different stains, including exocrine markers of acinar differentiation (trypsin, chymotrypsin), ductal differentiation (glycoproteins), and neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin and chromogranin). They found that the most consistently positive markers were vimentin, NSE, α1-antitrypsin, α1- antichymotrypsin and progesterone receptors, present in more than 90% of tumors. Cytokeratin was demonstrated in 70% and synaptophysin in 22%. However, their results failed to reveal a clear phenotypic relationship with any of the defined cell lines of the pancreas. Differentiation along exocrine cell lines has been postulated for SPT on the basis of trypsin and chymotrypsin positivity. However, NSE and synaptophysin[9] positivity favors an endocrine origin. The female predominance along with the presence of progesterone receptors[9-11] in some reported cases suggests a neuroendocrine origin. In a study by Pezzi, SPT had immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evidence of both an endocrine and acinar-ductal differentiation, suggesting that this tumor may arise from a pluripotent stem cell[12]. While progesterone receptors have been found by some investigators, estrogen receptors have not been demonstrated[11,14]. Another hypothesis by Kosmahl is that there is a close relationship between the pancreas and the genital ridges during embryogenesis, so that the tumor cells may be derived from the celomic epithelium and rete ovarii[9]. These stem cells may become attached to pancreatic tissue during early embryogenesis[9,11].

The differential diagnosis of SPT of the pancreas includes any solid or cystic pancreatic disease entities, such as mucinous cystic tumor, microcystic adenoma, islet cell tumor, cystadenocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, inflammatory pseudocyst, mucus secreting tumor, pancreatoblastoma, and a vascular tumor-like hemangioma. The first four are usually seen in older patients and have no particular gender preponderance[13]. Pancreatoblastoma is usually found in younger individuals of either sex. Radiologically, a linear sunburst pattern of calcification is the usual finding in microcystic adenoma. A hypervascular pattern on angiography is suggestive of islet cell tumor rather than SPT[13].

Grossly, SPT is a well-encapsulated, spherical mass, usually measuring around 8 to 10 cm. The cut surface shows large spongy areas of hemorrhage alternating with both solid and cystic degeneration. The histological appearance is very distinctive and is considered diagnostic. It is fundam-entally a solid tumor with extensive degenerative changes forming solid cellular and hypervascular regions without glands. Areas of degeneration may then develop into pseudopapillary structures.

Nishihara[14] and colleagues showed that the presence of necrosis, vascular or perineural invasion, high nuclear grade, and prominent necrobiotic nests suggest a greater malignant potential and aggressive behavior. Another study reported a case of hepatic metastases in which there was DNA aneuploidy and an elevated proliferative index[15]. In our series, four patients had some such histologic findings, such as an incomplete capsule, perineural or perivascular invasion, and infiltration of tumor cells into the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma and spleen (cases 2, 3, 4, and 7). However, the one patient (case 1) who eventually developed metastatic disease did not have microscopic features suggesting a high malignant potential when she was first operated on. Therefore, in view of the relatively indolent biology of SPT, it is difficult to predict the prognosis accurately in any particular case. In some cases, tumors even smaller than the one in our male patient (case 7) had have been associated with more aggressive behavior. The fact that he was the oldest patient in our series is consistent with other reports[6,16] in terms of incidence. Although SPT is said to be more aggressive in older male patients, ours has remained well for at least 6 years.

In approximately 85% of patients, SPT is limited to the pancreas, while about 10% to 15% of tumors have already metastasized at the time of presentation[5]. The most common sites for metastasis are the liver, regional lymph nodes, mesentery, omentum, and peritoneum. We have found no other reports of splenic metastases. Although we did not have tissue proof of metastasis in the spleen in case 1, the radiologic features were very similar to those in the liver, in which there were biopsy-proven metastases. However, the original tumor was tightly adherent to the spleen, so we can not exclude the possibility of direct rather than metastatic spread of the tumor to the spleen.

One study demonstrated that even patients with local recurrence as well as liver and peritoneal metastases could still have long-term survival[16], our patient died of metastases within one year of diagnosis. Metastases reportedly occur at a mean interval of 8.5 years[17], usually in older patients (over 36 years)[16]. However our patient was much younger and had a prolonged disease-free interval compared to previous reports. It may be that the biologic malignancy of SPT increases with the aging of the tumor cells themselves.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, which is usually curative for localized disease. There is evidence for prolonged survival after adequate surgical resection even with metastases. Even if the disease is extensive at the time of presentation, surgical debulking favors prolonged survival[18]. Intra-operative frozen section may be helpful to ascertain the adequate of the resection margins. There have been only few reports of the use of radiotherapy[19] or chemotherapy[20], so it’s difficult to judge the value of such measures.

In conclusion, SPT of the pancreas is a rare indolent neoplasm with an unclear origin that typically occurs in young females. The diagnosis depends on histologic confirmation, but its appearance on imaging is fairly characteristic, being a large well-encapsulated mass with calcification and areas of hemorrhagic degeneration. Surgical resection has generally been curative, but close follow up is advisable, particularly when the histologic characteristics suggest a more aggressive tumor.

Assistant Editor Guo SY Edited by Gabbe M

| 1. | Dong PR, Lu DS, Degregario F, Fell SC, Au A, Kadell BM. Solid and papillary neoplasm of the pancreas: radiological-pathological study of five cases and review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:702-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Crawford BE. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas, diagnosis by cytology. South Med J. 1998;91:973-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Frantz VK. Papillary tumors of the pancreas: Benign or malignant? Tumors of the pancreas. Atlas of tumor Pathology, 1st Series, Fascicles 27 and 28. Frantz VK (ed). Washington. DC, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1959: 32-33. . |

| 4. | Kloppel G, Solcia E, Longnecker DS, Capella C, Sobin LH. World Health Organization, Institutional histological classification of tumors. Histological Typing of Tumors of the Exocrine Pancreas, 2 nd ed. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 1996;. |

| 5. | Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico DR, Kim K, Thomford NR, Howard JM. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and cumulative review of the world's literature. Surgery. 1995;118:821-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lam KY, Lo CY, Fan ST. Pancreatic solid-cystic-papillary tumor: clinicopathologic features in eight patients from Hong Kong and review of the literature. World J Surg. 1999;23:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Procacci C, Graziani R, Bicego E, Zicari M, Bergamo Andreis IA, Zamboni G, Iacono C, Mainardi P, Valdo M, Pistolesi GF. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: radiological findings. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:554-558. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Cantisani V, Mortele KJ, Levy A, Glickman JN, Ricci P, Passariello R, Ros PR, Silverman SG. MR imaging features of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Jänig U, Harms D, Klöppel G. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: its origin revisited. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:473-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ladanyi M, Mulay S, Arseneau J, Bettez P. Estrogen and progesterone receptor determination in the papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. With immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1987;60:1604-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zamboni G, Bonetti F, Scarpa A, Pelosi G, Doglioni C, Iannucci A, Castelli P, Balercia G, Aldovini D, Bellomi A. Expression of progesterone receptors in solid-cystic tumour of the pancreas: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of ten cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;423:425-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pezzi CM, Schuerch C, Erlandson RA, Deitrick J. Papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 1988;37:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zinner MJ, Shurbaji MS, Cameron JL. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasms of the pancreas. Surgery. 1990;108:475-480. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nishihara K, Nagoshi M, Tsuneyoshi M, Yamaguchi K, Hayashi I. Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas. Assessment of their malignant potential. Cancer. 1993;71:82-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kamei K, Funabiki T, Ochiai M, Amano H, Kasahara M, Sakamoto T. Three cases of solid and cystic tumor of the pancreas. Analysis comparing the histopathological findings and DNA histograms. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:269-278. [PubMed] |

| 16. | González-Cámpora R, Rios Martin JJ, Villar Rodriguez JL, Otal Salaverri C, Hevia Vazquez A, Valladolid JM, Portillo M, Galera Davidson H. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with liver metastasis coexisting with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:268-273. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Matsunou H, Konishi F. Papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study concerning the tumor aging and malignancy of nine cases. Cancer. 1990;65:283-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rebhandl W, Felberbauer FX, Puig S, Paya K, Hochschorner S, Barlan M, Horcher E. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in children: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Strauss JF, Hirsch VJ, Rubey CN, Pollock M. Resection of a solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas following treatment with cis-platinum and 5-fluorouracil: a case report. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1993;21:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fried P, Cooper J, Balthazar E, Fazzini E, Newall J. A role for radiotherapy in the treatment of solid and papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Cancer. 1985;56:2783-2785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |