Published online Nov 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7028

Revised: July 15, 2005

Accepted: July 20, 2005

Published online: November 28, 2005

AIM: This study shares Asian clinical experiences of carcinoid tumors that originated in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

METHODS: From May 1987 to June 2002, we had found only 13 cases of histologically confirmed carcinoid tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic examinations. There were eight males and five females. The mean age was 53.16±20.51 years that ranged from 26 to 82 years. Each of their clinical presentations, locations, tumor morphology, and size and the treatment outcome were analyzed and discussed.

RESULTS: One patient had a polypoid lesion at the lower esophagus, nine were stomach lesions and three located at the duodenum. All patients with polypoid and submucosal tumor types were of small size (<1.7 cm) and all patients survived after simple excision or polypectomy. Four of the five patients in tumor mass forms died and the tumors were more than 2.0 cm in size.

CONCLUSION: Carcinoid tumors rarely originated from the upper gastrointestinal tract and are usually found accidentally after endoscopic study. Bigger size (more than 2 cm) tumor masses may indicate a more severe disease and poor prognosis.

- Citation: Chuah SK, Hu TH, Kuo CM, Chiu KW, Kuo CH, Wu KL, Chou YP, Lu SN, Chiou SS, Changchien CS, Eng HL. Upper gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors incidentally found by endoscopic examinations. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(44): 7028-7032

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i44/7028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7028

Carcinoid tumors are a type of very slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors that originate from the embryonic neural crest. Their prominent feature is the production of multiple hormones[1]. The incidence is increasing at rates around 24.7-44.8 cases per million in the United States each year. Over 90% of all carcinoid tumors originate in the GI tract. Most carcinoid tumors are GI in origin, yet they only account for 1.5% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms. Most carcinoids are, in fact, found incidentally. Neither cytology nor histology can determine if the lesion is benign or malignant. Only the presence of distant metastases confirms malignancy.

However, all carcinoids must be considered malignant when found because of the high threat of metastasis. Although carcinoids <1 cm in diameter are unlikely to metastasize, a wide excision is recommended[1]. Five-year survival rates of patients with a local excision of carcinoid are >95%, metastases to the liver constitute a dismal 20% 5-year survival rate. Therefore, early detection as with most cancers is, desirable. In the past 15 years, we found only 13 cases of upper gastrointestinal tract carcinoid tumors by endoscopic examination. We tried to analyze and correlate the clinical settings, the sizes of tumors, their morphology, and the outcome of the disease.

The medical records of these 13 patients who were diagnosed as upper GI carcinoid tumors at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung Center, Taiwan from May 1987 to June 2002 were reviewed. We excluded all the cases with an uncertain diagnosis, small-bowel cancers found in the GI tract but thought to have metastasized there from an extra-abdominal primary site, and patients were operated on for periampullary tumors. The final study population composed of 13 patients who were treated. There were eight males and five females. The mean age was 53.15±20.51 years ranging from 26 to 82 years (Figure 1).

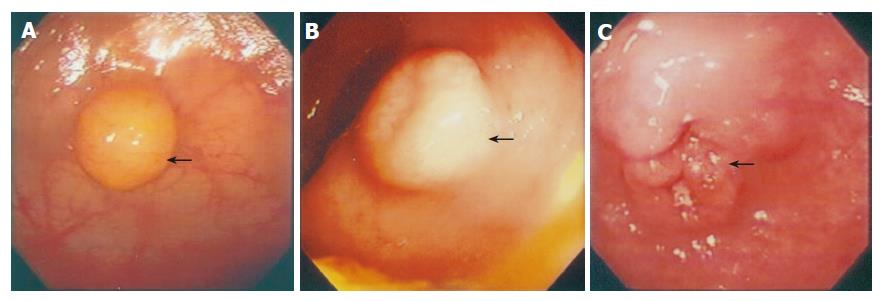

The morphology of the tumors observed by endoscopic examinations was divided into three main categories: polypoid (Figure 2A), submucosal (Figure 2B), tumor-like (Figure 2C) lesions. A single surgical pathologist reviewed pathological specimens and histological features. Routine hematoxylin-eosin stains, immunohistochemistry, or elevated urinary 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid levels established the diagnosis of carcinoid tumor. Survival duration was measured from the time of diagnosis to the last follow-up evaluation or death. The follow-up observations were obtained from the medical records of the patients or direct contact with the patients, their relatives, or primary care physician. The endoscopic observations of the lesions such as the morphologic appearance and the sizes were analyzed in correlation to the treatment course and prognosis of each recorded patient (Table 1).

| Patients | Age (yr) | Sex | Symptom | Location | Morphology | Size(cm) | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | 26 | Male | GI bleeding | Esophagus | Polyp | 0.7 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 2 | 81 | Female | GI bleeding | Stomach | Polyp | 0.4 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 3 | 33 | Female | Epigastralgia | Stomach | ST | 0.9 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 4 | 26 | Female | Epigastralgia | Stomach | ST | 1 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 5 | 70 | Female | Epigastralgia | Stomach | Polyp | 0.5 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 6 | 63 | Male | Abdominal pain | Stomach | Tumor | 10 | Surgery | (Expired) |

| 7 | 46 | Male | GI bleeding | Stomach | ST | 4.3 | Surgery | (Survive) |

| 8 | 62 | Male | GI bleeding | Stomach | Tumor | 4 | Surgery | (Expired) |

| 9 | 68 | Male | Epigastralgia | Stomach | Tumor | 1.5 | Surgery | (Survive) |

| 10 | 30 | Male | Epigastralgia | Stomach | Tumor | >4.0 | Supportive care | (Expired) |

| 11 | 64 | Female | Epigastralgia | Duodenum (bulb) | Polyp | 0.9 | Polypectomy | (Survive) |

| 12 | 40 | Male | Epigastralgia | Duodenum (bulb) | ST | 1.7 | Duodenectomy | (Survive) |

| 13 | 82 | Male | Jaundice | Duodenum (second portion) | Tumor | >2.0 | Stenting | (Expired) |

This study group included eight men and five women, with the median follow-up duration of 36 mo. The most common symptom was abdominal pain (53%), followed by weight loss (38.5%), GI tract bleeding (23%) and jaundice (7.7%). Some patients had more than one symptom or physical finding, though no combination of signs, symptoms, or acuity of presentation was thought to have any influence on the prognosis.

Only one 26-year-old male patient had a 0.7-cm esophageal carcinoid lesion, polypoid in appearance and located at the lower esophagus. Polypectomy was done for him and no signs of recurrence for more than 5 years. Nine patients suffered from gastric carcinoid tumors and three of them died. All these three patients had gastric tumor masses of at least 4 cm in size found by endoscope. One patient had tumor involving colon, spleen, and pancreas, while the other had metastatic mesenteric lymphnodes. Both underwent surgery but still failed to survive due to sepsis and organ failure.

A 30-year-old female had a huge mass over the pelvis extended to almost the whole of the left side abdomen. Endoscope showed a 4.0-cm ulcerated mass over the cardiac portion and fundus. Carcinoid tumor was proven by snare biopsy. She also suffered from a septic right knee. Due to the poor general condition, she received supportive treatment only. One 68-year-old male patient had a 1.5-cm tumor mass at gastric antrum who received complete resection already and survived for 6 years. One 46-year-old male patient had been suffering from repeated gastro-duodenal ulcers bleeding. Scope reviewed a more than 4 cm slightly elevated submucosal lesion at the antrum. Computer tomography and angiography showed a tumor mass bulging out posterior to the stomach. He had been well after surgical resection of the antrum.

All four patients who had gastric carcinoid lesions smaller than 1.0 cm survived, and the morphology were polypoid (n = 2) and appearance of submucosa (n = 2). Two received polypectomies and two mucosectomies and there are no signs of recurrence so far.

Three patients had duodenal carcinoid lesions, two located in the duodenal bulb and one in the second portion of the duodenum. One 64-year-old female patient had a 0.9-cm polypoid lesion at the bulb portion, and polypectomy was performed. The other 40-year-old male patient who had a 1.7-cm submucosal lesion at bulb received duodenectomy. Both of them are still alive and disease-free at 4 and 6 years status post therapy. However, one 82-year-old female patient who suffered from obstructive jaundice by a carcinoid tumor mass at the duodenal second portion was not as fortunate. Stent was placed by using endoscope to relieve her obstructive jaundice but she still died because of sepsis shortly after.

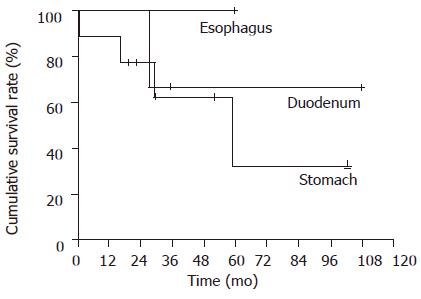

The cumulative 5-year survival rate was 64% in the carcinoid tumor. Gastric carcinoid had the worse prognosis in this study with 5-year survival of less than 40%. Duodenal carcinoid tumor had a 5-year survival of about 60%. Only one case was found with a carcinoid in the esophagus and the patient is still surviving but the total number of patients is too small to come to any conclusion.

Carcinoid tumor of the esophagus is exceedingly rare, and the knowledge about this tumor is based primarily on case reports[2]. Several case reports have emphasized that esophageal carcinoid tumors are associated with a poor prognosis[2]. Primary endocrine tumors of the esophagus are rare tumors that include small cell carcinoma, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, atypical carcinoid tumor, classical carcinoid tumor, and combined endocrine tumor and adenocarcinoma[2]. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus accounts for 1% of all esophageal tumors, and the overall median survival is 3.1 mo[3]. The only one case, who had a small polyp at distal esophagus, still survives, 50 mo after endoscopic polypectomy. Although only one case was treated, it supported that esophageal carcinoid tumors are not always associated with a poor prognosis probably as a non-small cell carcinoma.

Three types of gastric carcinoids have been described[4,5]. Type I is associated with chronic atrophic body-fundus gastritis type A. Type II is seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome/multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN-1) syndrome. Type III is a sporadic tumor[6]. Gastric carcinoids arise from endocrine cells in gastric mucosa and recent reports indicate that 10-30% of all gastrointestinal carcinoids occur in the stomach[6].

Type I gastric carcinoids is the most frequent type encountered in about 65% of cases[7]. The tumors are usually small (<1 cm) polypoid lesions located in the gastric body or fundus[8]. Adjacent atrophic mucosa contains foci of precursor lesions, which are at different stages of ECL cell hyperplasia, dysplasia, and neoplasia. Hypergastrinemia is usually present[6]. Nodal metastasis is reported in up to 16% of cases and hepatic metastasis, in up to 4%[9]. Endocrine symptoms are rare; 5-year survival is high in our series, four gastric carcinoids were less than 1.0 cm in size, either in polypoid or submucosal in morphology endoscopically. Polypectomies and endoscopic mucosectomy were performed smoothly and they still survive.

One of our patients who belonged to type II gastric carcinoids suffered from repeated GI bleeding and hypergastrinemia. After receiving operation, he is still healthy. The adjacent mucosa is non-atrophic and entirely comprised precursor lesions[6]. Prognosis is intermediate, between types I and III[7].

Type III gastric lesions make about 20% of gastric carcinoids[6]. Forty percent occur in the antropyloric area[6] when discovered; they are usually single tumor more than 2 cm. They arise from ECL, EC, or X cells. There is no hypergastrinemia and no precursor lesions. They can cause either a classic syndrome of facial flushing, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, left-sided endocardial fibrosis, and 24 h urinary 5-HIAA more than 10 mg, or an atypical carcinoid syndrome associated with vasoactive substances and polypeptide hormone production[6]. Nodal metastasis is reported in 55% of patients and liver metastases, in 25% of patients[5]. Five-year survival is only 50%[7]. All the four of our patients with gastric tumor masses of more than 4 cm in size were associated with adjacent and distant metastasis. Two had carcinoid syndrome. Three received surgical intervention and one had supportive care. Three of them expired.

Schneider et al[10] showed that the patients with gastric carcinoids had an eight times higher risk of developing a secondary malignancy as compared with the normal population. None of our gastric carcinoids had secondary carcinomas so far.

The management of gastric carcinoids depends on the type; presence of symptoms, or metastases spread, size, and number of tumors[6]. Although multiple studies have been published, the treatment in many cases still remains controversial. Most agreed on the management of type III (or sporadic) carcinoids, which have the worst prognosis and the highest rate of metastasis and associated carcinoid syndrome[6]. The recommended therapy is en bloc surgical resection with regional lymph node dissection, especially for lesions of more than 2 cm[5,11,12]. If the tumor penetrated the serosa, gastrectomy is also recommended[13].

For the patients with liver metastasis, surgical resection of tumor foci or selective hepatic artery ligation or embolization may reduce the symptoms and improve survival[6]. Chemotherapy of disseminated disease with streptozocin, 5-FU, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin were reported to produce a 20-40% response rate[6]. Leukocyte interferon produced a temporary response in some patients[5]. Somatostatin analogs, octreotide, and lanreotide have been used successfully in recent years to relieve the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome[14]. Recently, the results of trials with long-acting formulations octreotide-LAR (10, 20, or 30 mg every 28 d) and lanreotide-PR (30 mg every 2 wk) were published and demonstrated effectiveness and convenience of the treatment[15-18].

The optimal management of the types I and II gastric carcinoids is less clear[6]. Many authors base their recommendations on the size and number of the tumors[6]. For lesions less than 1 cm in diameter and less than 3-5 in number, endoscopic removal and semiannual EGD surveillance is recommended[6]. If there is a recurrence, or if the lesions are larger than 1 cm or more than 3-5 in number, then antrectomy with endoscopic excision is recommended[5,13].

Type I is considered as the most benign type of gastric carcinoids, rarely affecting the 5-year survival[8]. There are strong arguments supporting surgery[6]. Although type I carcinoid is the most benign type, it is still associated with some incidence of lymph node and liver metastasis[7,8]. Most gastric carcinoids regress after antrectomy[12,19,20]. In contrast, improved overall survival for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors after the complete resection of primary and hepatic metastases is accomplished, with an actuarial 5-year survival rate of 70%.

Carcinoid tumor was the most common small bowel tumor. It occurred in 24% of patients. Forty-six percent of patients were asymptomatic during life, the tumors being found either at autopsy or during other surgical procedures. Of those that were symptomatic, half presented with intestinal obstruction and the rest with long-standing symptoms. An abdominal mass, which occurred in 14% of cases, is an uncommon physical finding since the majority present as small submucosal tumors. Fifty-eight percent overall and 72% of those having surgery had evidence of regional spread, either by local invasion or in the form of regional nodal involvement. Seven percent of patients have died because of their disease. Excision surgery should be performed for all cases where feasible, and repeated for recurrent symptoms[21].

Ampullary carcinoids are rare tumors. Like the 82-year-old male in our series, they most commonly present with obstructive symptoms like jaundice and nonspecific abdominal discomfort. They are difficult to diagnose preoperatively secondary to their relatively small size and submucosal location. Rarely, ulcerated duodenal carcinoids can present as a source of significant gastrointestinal bleeding. Overall, approximately 80-90% of all carcinoids secrete serotonin or its precursor 5-hydroxy tryptophan, and other tumors rarely do so. Measurements of serotonin and its metabolites like urinary 5-hydroxy indole acetic acid (5-HIAA) have been described to be very helpful in the diagnosis and postresection follow-up of carcinoids. In our patient, those levels were not obtained preoperatively as the patient did not have any signs, symptoms, or histologic evidence to suggest a diagnosis of carcinoid tumor[22].

In conclusion, carcinoid tumors rarely originated from the upper gastrointestinal tract in the eastern countries and are usually found incidentally after endoscopic study. Bigger size (more than 2 cm) tumor mass form may indicate a more severe disease and poor prognosis.

Co-first authors: Seng-Kee Chuah and Tsung-Hui Hu

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Onaitis MW, Kirshbom PM, Hayward TZ, Quayle FJ, Feldman JM, Seigler HF, Tyler DS. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: characterization by site of origin and hormone production. Ann Surg. 2000;232:549-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hoang MP, Hobbs CM, Sobin LH, Albores-Saavedra J. Carcinoid tumor of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic study of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Law SY, Fok M, Lam KY, Loke SL, Ma LT, Wong J. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1994;73:2894-2899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:994-1006. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Creutzfeldt W. The achlorhydria-carcinoid sequence: role of gastrin. Digestion. 1988;39:61-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rybalov S, Kotler DP. Gastric carcinoids in a patient with pernicious anemia and familial adenomatous polyposis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:249-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahlman H, Kölby L, Lundell L, Olbe L, Wängberg B, Granérus G, Grimelius L, Nilsson O. Clinical management of gastric carcinoid tumors. Digestion. 1994;55 Suppl 3:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Borch K. Atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoid tumours. Ann Med. 1989;21:291-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Higham AD, Dimaline R, Varro A, Attwood S, Armstrong G, Dockray GJ, Thompson DG. Octreotide suppression test predicts beneficial outcome from antrectomy in a patient with gastric carcinoid tumor. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:817-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schneider C, Wittekind C, Köckerling F. An unusual incidence of carcinoid tumors and secondary malignancies. Chirurg. 1995;66:607-611. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Modlin IM, Gilligan CJ, Lawton GP, Tang LH, West AB, Darr U. Gastric carcinoids. The Yale Experience. Arch Surg. 1995;130:250-255; discussion 250-255;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thirlby RC. Management of patients with gastric carcinoid tumors. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:296-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ahrén B, Borch K. Multiple gastric carcinoid tumours. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:375. [PubMed] |

| 14. | O'Toole D, Ducreux M, Bommelaer G, Wemeau JL, Bouché O, Catus F, Blumberg J, Ruszniewski P. Treatment of carcinoid syndrome: a prospective crossover evaluation of lanreotide versus octreotide in terms of efficacy, patient acceptability, and tolerance. Cancer. 2000;88:770-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bajetta E, Bichisao E, Artale S, Celio L, Ferrari L, Di Bartolomeo M, Zilembo N, Stani SC, Buzzoni R. New clinical trials for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Q J Nucl Med. 2000;44:96-101. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ricci S, Antonuzzo A, Galli L, Orlandini C, Ferdeghini M, Boni G, Roncella M, Mosca F, Conte PF. Long-acting depot lanreotide in the treatment of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anthony LB. Long-acting formulations of somatostatin analogues. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 2:S216-S218. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Tomassetti P, Migliori M, Corinaldesi R, Gullo L. Treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours with octreotide LAR. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hirschowitz BI, Griffith J, Pellegrin D, Cummings OW. Rapid regression of enterochromaffinlike cell gastric carcinoids in pernicious anemia after antrectomy. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1409-1418. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Richards AT, Hinder RA, Harrison AC. Gastric carcinoid tumours associated with hypergastrinaemia and pernicious anaemia--regression of tumors by antrectomy. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1987;72:51-53. [PubMed] |

| 21. | O'Rourke MG, Lancashire RP, Vattoune JR. Carcinoid of the small intestine. Aust N Z J Surg. 1986;56:405-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Singh VV, Bhutani MS, Draganov P. Carcinoid of the minor papilla in incomplete pancreas divisum presenting as acute relapsing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27:96-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |