Published online Nov 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.6936

Revised: May 23, 2005

Accepted: May 25, 2005

Published online: November 28, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the expression of fibrinogen-like protein 2 (fgl2) and its correlation with disease progression in both mice and patients with severe viral hepatitis.

METHODS: Balb/cJ or A/J mice were infected intraperitoneally (ip) with 100 PFU of murine hepatitis virus type 3 (MHV-3), liver and serum were harvested at 24, 48, and 72 h post infection for further use. Liver tissues were obtained from 23 patients with severe acute chronic (AOC) hepatitis B and 13 patients with mild chronic hepatitis B. Fourteen patients with mild chronic hepatitis B with cirrhosis and 4 liver donors served as normal controls. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from 30 patients (unpaired) with severe AOC hepatitis B and 10 healthy volunteers as controls. Procoagulant activity representing functional prothrombinase activity in PBMC and white blood cells was also assayed. A polyclonal antibody against fgl2 was used to detect the expression of both mouse and human fgl2 protein in liver samples as well as in PBMC by immunohistochemistry staining in a separate set of studies. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (TBil) in serum were measured to assess the severity of liver injury.

RESULTS: Histological changes were found in liver sections 12-24 h post MHV-3 infection in Balb/cJ mice. In association with changes in liver histology, marked elevations in serum ALT and TBil were observed. Mouse fgl2 (mfgl2) protein was detected in the endothelium of intrahepatic veins and hepatic sinusoids within the liver 24 h after MHV-3 infection. Liver tissues from the patients with severe AOC hepatitis B had classical pathological features of acute necroinflammation. Human fgl2 (hfgl2) was detected in 21 of 23 patients (91.30%) with severe AOC hepatitis B, while only 1 of 13 patients (7.69%) with mild chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis had hfgl2 mRNA or protein expression. Twenty-eight of thirty patients (93.33%) with severe AOC hepatitis B and 1 of 10 with mild chronic hepatitis B had detectable hfgl2 expression in PBMC. No hfgl2 expression was found either in the liver tissue or in the PBMC from normal donors. There was a positive correlation between hfgl2 expression and the severity of the liver disease as indicated by the levels of TBil. PCA significantly increased in PBMC in patients with severe AOC hepatitis B.

CONCLUSION: The molecular and cellular results reported here in both mice and patients with severe viral hepatitis suggest that virus-induced hfgl2 prothrombinase/fibroleukin expression and the coagulation activity associated with the encoded fgl2 protein play a pivotal role in initiating severe hepatitis. The measurement of hfgl2/fibroleukin expression in PBMC may serve as a useful marker to monitor the severity of AOC hepatitis B and a target for therapeutic intervention.

- Citation: Zhu CL, Yan WM, Zhu F, Zhu YF, Xi D, Tian DY, Levy G, Luo XP, Ning Q. Fibrinogen-like protein 2 fibroleukin expression and its correlation with disease progression in murine hepatitis virus type 3-induced fulminant hepatitis and in patients with severe viral hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(44): 6936-6940

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i44/6936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.6936

Viral hepatitis remains a major public health problem and the most common type of liver disease worldwide[1,2]. There are an increasing number of patients with chronic hepatitis B who develop acute hepatitis on chronic condition (AOC) and die of acute hepatic failure both as a result of our lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease and lack of effective treatment[3]. The hallmark of AOC is the extreme rapidity of the necro-microinflammatory process resulting in widespread or total hepatocellular necrosis in weeks or even in days[3]. Our previous studies have shown that macrophage activation and expression of fgl2, encoding a serine protease capable of directly cleaving prothrombin to thrombin, result in widespread fibrin deposition within the liver and hepatocyte necrosis[3-6]. The present study was designed to assess the expression of fgl2 and its correlation with disease progression in both mice and patients with severe viral hepatitis.

MHV-3 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), plaque was purified on monolayers of DBT cells and grown to a titer of 1×106 PFU/mL in 17 CL cells. Viral titers were determined on monolayers of L2 cells by a standard plaque assay as described elsewhere[5].

Female Balb/cJ mice, 8-10 wk of age and weighing 20-22 g, were purchased from Hubei Provincial Institute of Science and Technology. Female A/J mice, 8-10 wk of age and weighing 20-22 g, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).

The affinity-purified polyclonal antibody to both murine and human fgl2 prothrombinases was produced by 21 repeated injections into rabbits with a 14-amino-acid hydrophilic peptide (CKLQADDHRDPGGN) from exon 1 of the fgl2 prothrombinase coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Rabbit brain thromboplastin was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA).

All animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of the Chinese Council on Animal Care and approved by the Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College Committees on Animal Experimentation. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Hospital Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. All mice were housed in the animal facility in Tongji Hospital. Mice received 100 PFU of MHV-3 by intraperitoneal injection. The liver and serum were collected from both Balb/cJ and A/J mice 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after intraperitoneal injection of MHV-3.

Biochemical, histological, and clinical features were used to define patients with severe AOC hepatitis B or mild chronic viral hepatitis B and compensated cirrhosis. The patients with chronic viral hepatitis B were evaluated on the basis of a thorough history and physical examination with special emphasis on risk factors for co-infection (with hepatitis C, D, or HIV), alcohol use, family history of viral hepatitis B and liver cancer. Liver tissues were obtained by biopsies from patients in 1995-2001, including 23 severe AOC hepatitis B patients (20 males and 3 females, 36.0±7.8 years on average with a mortality of 82% ALT 586.0±570.2 IU/L, TBil 452.9±227.2 μmol/L, and PT 35±10 s), 13 mild chronic hepatitis B patients (11 males and 2 females, 43.8±5.6 years on average, ALT 300.5±325.2 IU/L, TBil 78.3±175.4 μmol/L, and PT 12±1 s), 14 compensated cirrhosis hepatitis B patients (all males, 45.0±8.6 years on average, ALT 265.3±215.8 IU/L and TBil 46.6±27.6 μmol/L, PT 14±2 s). All mild chronic hepatitis B and compensated cirrhotic hepatitis B patients recovered from the disease. There were no significant differences in HBV DNA levels among different groups of patients. Liver biopsies were performed within 30 min after the patients died of acute hepatic failure. Liver samples were also obtained from four liver donors as normal controls. PBMCs were freshly isolated from 30 patients (all males, 37.7±9.1 years on average) with severe AOC hepatitis B, elevated ALT (108.9±75.2 IU/L) and TBil (389.3±116.9 μmol/L), elevated PT (40±31 s). Ten mild chronic hepatitis B patients (8 males and 2 females, 34.0±10.5 years on average) had normal ALT and TBil. The isolated PBMCs were smeared on slides and kept at -80 °C for further study. Liver tissue histological sections were stained with hemotoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the fgl2 prothrombinase as described previously[3,6].

PBMC and white blood cells (WBC) were evaluated for functional PCA in a one-stage clotting assay. Freshly isolated PBMC and WBC were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.0) and resuspended at a concentration of 106/mL. Samples were assayed for the ability to shorten the spontaneous clotting time of normal citrated human platelet-poor plasma. Milliunits of PCA were assigned by reference to a standard curve generated with serial log dilutions of a standard rabbit brain thromboplastin as described previously[2].

Quantitative data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was carried out by one-way analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

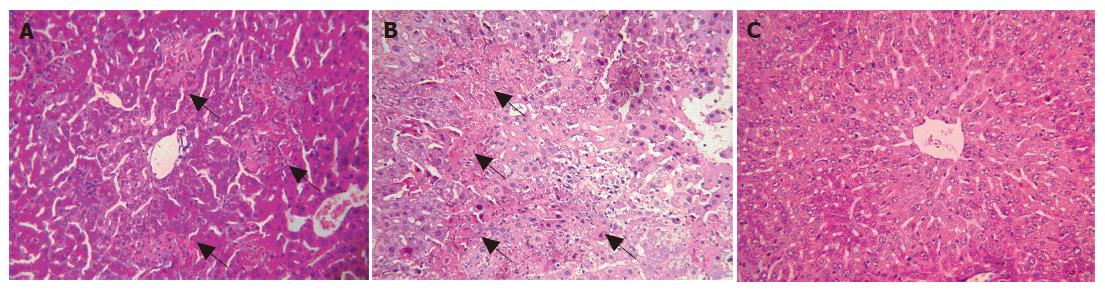

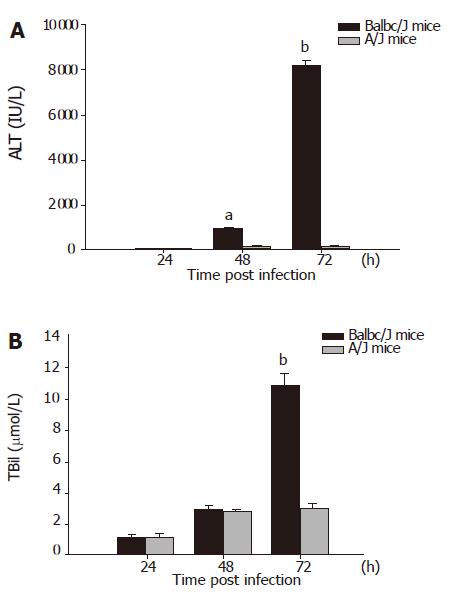

Small and discrete foci of necrosis with sparse polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltrates were seen 12-24 h after MHV-3 infection. After 48 h, the area of these lesions enlarged and became confluent necroses (Figures 1A and 1B). There was no evidence of necrosis in the livers of MHV-3 infected A/J mice (Figure 1C). In Balb/cJ mice, serum ALT and TBil levels increased after 16-24 h, peaked at 72 h and remained elevated thereafter, while there were no significant ALT and TBil changes in MHV-3-infected A/J mice (Figures 2A and 2B).

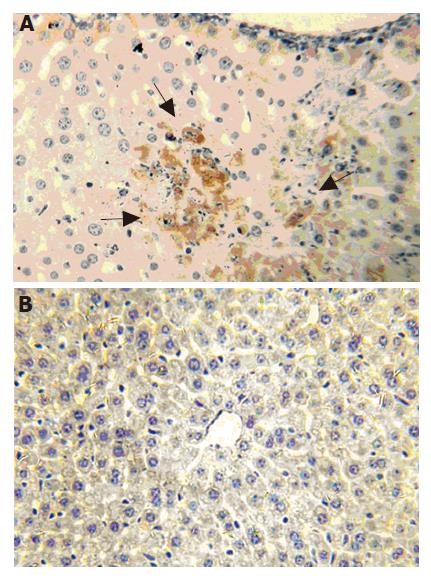

mfgl2 prothrombinase expression increased in MHV-3-infected Balb/cJ mice starting from 12 to 24 h (Figure 3A) and was sustained until the animals died days after infection (data not shown). There was no evidence of mfgl2 staining in normal Balb/cJ mice (data not shown) or MHV-3-infected A/J mice (Figure 3B).

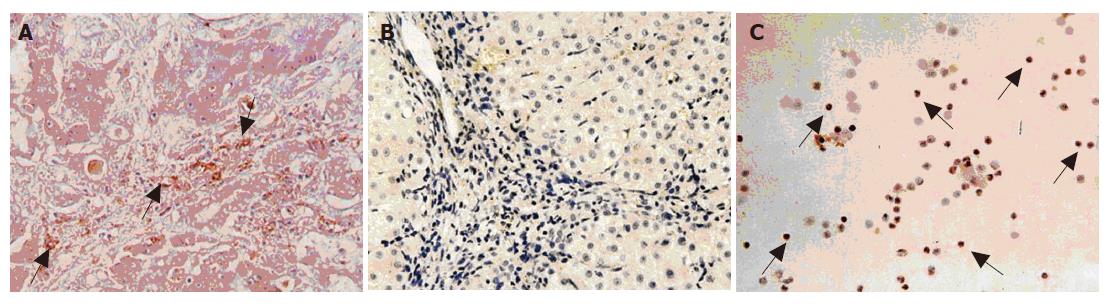

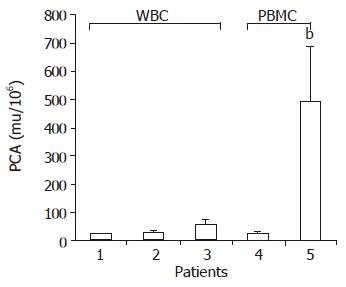

Hfgl2 was detected in 21 of 23 patients (91.30%) with severe AOC hepatitis B (Figure 4A), while only 1 of 13 patients (7.69%) with mild chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis (no evidence of active disease) had hfgl2 mRNA or protein expression. Twenty-eight of thirty patients with severe AOC hepatitis B (93.33%) and 1 of 10 with mild chronic hepatitis B had detectable hfgl2 expression in PBMC (Figure 4C). There was no hfgl2 expression either in the liver tissue or in the PBMC from the normal donors. There was a significant increase in PCA activity in patients with serve AOC hepatitis B compared to patients with mild chronic hepatitis B, while there was no significant difference in PCA in various groups of patients (Figure 5).

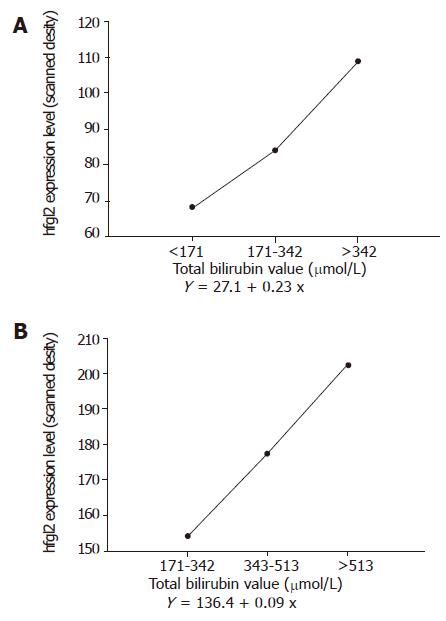

Hfgl2 expression both in liver and in PBMC was semi-quantified by a MPIAS-500 scanning analysis system. The data indicated that there was a close correlation between hfgl2 expression and the severity of the disease as shown in Figures 6A and 6B.

The inability to propagate human hepatitis viruses in culture and the lack of suitable animal models have impeded the determination of the pathological mechanisms of fulminant hepatic failure (FHF). However, animal models of FHF induced by murine hepatitis virus strain 3[4,7], transgenic models of hepatitis B virus infection[8,9] and clinical cases of FHF have provided insights into the pathogenesis of viral FHF[3,6]. MHV-3 produces a broad spectrum of diseases, including pneumonitis, encephalitis, enterocolitis, nephritis, and hepatitis[10,11]. This report demonstrated that Balb/cJ mice after MHV-3 infection developed fulminant viral hepatitis. HE staining showed infiltration of lymphocytes and massive hepatic necrosis in association with mfgl2 expression in the endothelial cells of hepatic sinusoids and in areas of focal necrosis. The serum ALT and bilirubin levels reflected the damage of liver tissue in MHV-3-induced FHF in Balb/cJ mice. In contrast, there was no or only minor hepatocyte injury with no mfgl2 in MHV-3-infected A/J mice. Therefore, these results further demonstrate that though MHV-3 replicates in tissues of both resistant and susceptible animals, suggesting that host factors may be more critical than viral replication in the pathogenesis of MHV-induced hepatitis. Our previous study have demonstrated that MHV-3 infection of macrophages results in transcription of host inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, and superoxides[4]. Cytokines can play an important role in the course of inflammatory injury in vivo, and interference with their action can alter the course of inflammatory diseases[12-15]. The importance of mfgl2 prothrombinase in the pathogenesis of MHV-3 infection is supported by the observation that a neutralizing antibody to this protein prevents fibrin deposition and protects mice from the lethality of MHV-3 infection. Furthermore, mfgl2 knockout mice lack fibrin deposition and liver necrosis and survival increased from 0% to 33%[3,16].

To address the relevance of hfgl2 in human chronic viral hepatitis, we studied patients with both minimal and severe AOC hepatitis B. We detected robust expression of hfgl2 near or within the areas of hepatic necrosis and elevated levels of hfgl2 were seen in PBMC isolated from patients with severe AOC hepatitis B. These findings are in contrast to the lack of expression of hfgl2 in the livers and PBMC of patients with minimal chronic hepatitis B. Functional assay of hfgl2 prothrombinase in PBMC showed a robust increase of PCA in patients with severe AOC hepatitis B compared to patients with minimal chronic hepatitis B. Semiquantitative analysis of hfgl2 expression both in liver tissue and PBMC showed a close correlation with the severity of the disease as indicated by elevations in serum bilirubin levels. There was no significant difference in terms of HBeAg level and HBV DNA level between different groups of patients, further supporting that host factors may be critical in the pathogenesis of severe hepatitis.

In conclusion, MHV-3-induced hfgl2 prothrombinase/fibroleukin expression and the potent function of the protein it encodes play a pivotal role in initiating both acute and fulminant hepatitis on chronic liver injury. The measurement of hfgl2 expression in PBMC may serve as a useful marker to monitor the severity of AOC hepatitis B and a target for therapeutic intervention.

Co-first-authors: Chuan-Long Zhu and Wei-Ming Yan

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Fattovich G. Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:47-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Levy GA, Liu M, Ding J, Yuwaraj S, Leibowitz J, Marsden PA, Ning Q, Kovalinka A, Phillips MJ. Molecular and functional analysis of the human prothrombinase gene (HFGL2) and its role in viral hepatitis. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1217-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marsden PA, Ning Q, Fung LS, Luo X, Chen Y, Mendicino M, Ghanekar A, Scott JA, Miller T, Chan CW. The Fgl2/fibroleukin prothrombinase contributes to immunologically mediated thrombosis in experimental and human viral hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ding JW, Ning Q, Liu MF, Lai A, Leibowitz J, Peltekian KM, Cole EH, Fung LS, Holloway C, Marsden PA. Fulminant hepatic failure in murine hepatitis virus strain 3 infection: tissue-specific expression of a novel fgl2 prothrombinase. J Virol. 1997;71:9223-9230. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ning Q, Brown D, Parodo J, Cattral M, Gorczynski R, Cole E, Fung L, Ding JW, Liu MF, Rotstein O. Ribavirin inhibits viral-induced macrophage production of TNF, IL-1, the procoagulant fgl2 prothrombinase and preserves Th1 cytokine production but inhibits Th2 cytokine response. J Immunol. 1998;160:3487-3493. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Chen Y, Ning Q, Wang BJ, Zhang DS, Yan FM, Sun Y, Xi D, Yan WM, Hao LJ. Expression of human fibroleukin gene acute on chronic hepatitis B and its clinical significance. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83:446-450. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ning Q, Berger L, Luo X, Yan W, Gong F, Dennis J, Levy G. STAT1 and STAT3 alpha/beta splice form activation predicts host responses in mouse hepatitis virus type 3 infection. J Med Virol. 2003;69:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guidotti LG, Morris A, Mendez H, Koch R, Silverman RH, Williams BR, Chisari FV. Interferon-regulated pathways that control hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 2002;76:2617-2621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guidotti LG, McClary H, Loudis JM, Chisari FV. Nitric oxide inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in the livers of transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1247-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ning Q, Luo XP, Wang ZM, Han MF, Yan WM, Liu MF, Levy G. The study of cis-element HNF4 in the regulation of mfg12 prothrombinase/fibroleukin gene expression in response to nucleocapsid protein of MHV-3. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83:678-683. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lai MM. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:61-79. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, Ghrayeb J, Reimann KA, Purcell RH, Chisari FV. CD8(+) T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 705] [Cited by in RCA: 763] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Major ME, Dahari H, Mihalik K, Puig M, Rice CM, Neumann AU, Feinstone SM. Hepatitis C virus kinetics and host responses associated with disease and outcome of infection in chimpanzees. Hepatology. 2004;39:1709-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McClary H, Koch R, Chisari FV, Guidotti LG. Relative sensitivity of hepatitis B virus and other hepatotropic viruses to the antiviral effects of cytokines. J Virol. 2000;74:2255-2264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wieland SF, Vega RG, Müller R, Evans CF, Hilbush B, Guidotti LG, Sutcliffe JG, Schultz PG, Chisari FV. Searching for interferon-induced genes that inhibit hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mouse hepatocytes. J Virol. 2003;77:1227-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li C, Fung LS, Chung S, Crow A, Myers-Mason N, Phillips MJ, Leibowitz JL, Cole E, Ottaway CA, Levy G. Monoclonal antiprothrombinase (3D4.3) prevents mortality from murine hepatitis virus (MHV-3) infection. J Exp Med. 1992;176:689-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |