Published online Nov 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6563

Revised: May 23, 2005

Accepted: May 24, 2005

Published online: November 7, 2005

The author presents three cases of esophageal rupture during the treatment of massive esophageal variceal bleeding with Sengstaken-Blakemore (SB) tube. In each case, simple auscultation was used to guide SB tube insertion, with chest radiograph obtained only after complete inflation of the gastric balloon. Two patients died of hemorrhagic shock and one died of mediastinitis. The author suggests that confirmation of SB tube placement by auscultation alone may not be adequate. Routine chest radiographs should be obtained before and after full inflation of the gastric balloon to confirm tube position and to detect tube dislocation.

- Citation: Chong CF. Esophageal rupture due to Sengstaken-Blakemore tube misplacement. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(41): 6563-6565

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i41/6563.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6563

Esophageal rupture is a well-known but rarely reported fatal complication of the management of bleeding esophageal varices with the Sengstaken-Blakemore (SB) tube[1]. Described below are three cases of fatal esophageal rupture with striking radiographs showing the gastric balloon of the SB tube inflated in the thoracic cavity. A routine pre-inflation chest radiograph should have prevented esophageal perforation due to malposition of the SB tube in these cases.

A 38-year-old man was admitted with massive hematemesis. On physical examination, his blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and temperature were 86/50 mmHg, 126 bpm, 24/min, and 37.3 °C, respectively. Pale conjunctivae, icteric sclera, splenomegaly, and spider angiomata were also observed. Resuscitation was started with normal saline, packed red cells and platelet concentrates. When stabilized, an emergency esophago-gastroduodenoscopy was performed, which revealed active bleeding from ruptured esophageal varices.

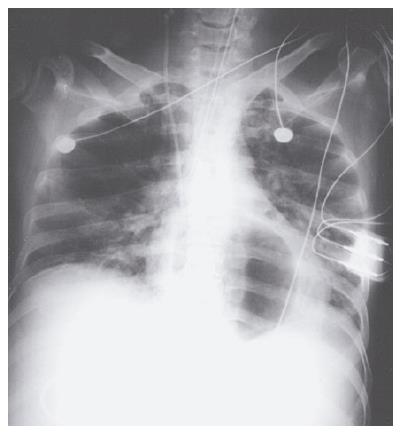

Despite aggressive therapies with fluids, blood components and full-dose terlipressin, the patient deteriorated into coma due to hemorrhagic shock. He was moved to the intensive care unit (ICU) for insertion of an SB tube. Endotracheal intubation was accomplished to secure airway before the procedure. A chest radiograph taken soon after tracheal intubation and inflation of the gastric balloon to 300 mL showed a radiolucent area behind the heart (Figure 1). The gastric balloon was immediately deflated and the SB tube removed (2 h after insertion). A repeated chest radiograph revealed massive left hemothorax. As the patient was deemed unfit for surgery, he was treated conservatively. The patient died when a further episode of massive hematemesis developed 44 h after admission.

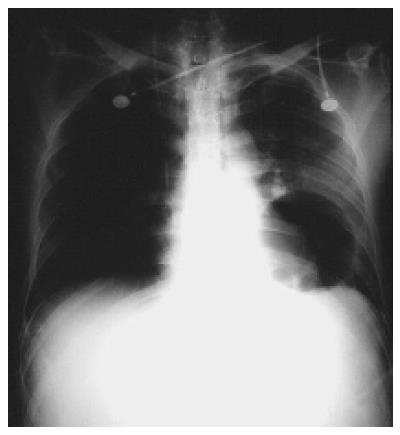

A 49-year-old man was admitted to the ICU due to uncontrolled hematemesis from ruptured esophageal varices and hepatic encephalopathy. Physical examination showed that he was in deep coma (Glasgow coma scale of E2M1V1) and severe hypotension (BP 60/40 mmHg). Rapid endotracheal intubation followed by insertion of an SB tube was performed without difficulties. However, a chest radiograph ordered to check tube positions demonstrated a radiolucent circle (the gastric balloon) within the left hemithorax (Figure 2). The patient died of shock-related multiple organ failure on the third day of admission.

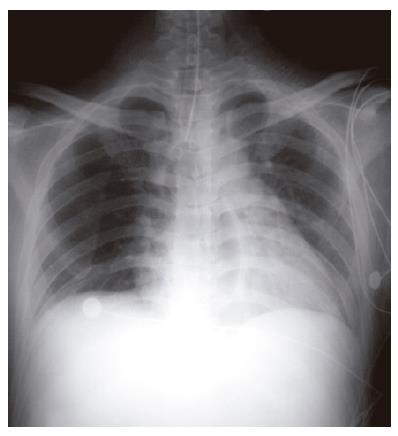

A 43-year-old male alcoholic was treated in the ICU for convulsions due to decompensated hepatic cirrhosis with grade IV encephalopathy. He was tracheally intubated with a Glasgow coma scale of E2M2VT. His vital signs were within the normal limits. However, he suffered a massive hematemesis on the third day of admission, which was the result of ruptured esophageal varices. An SB tube was inserted and a chest radiograph later showed a radiolucent area within the lower mediastinum (Figure 3). The patient developed fever, leukocytosis and shock in the following days and a chest computer tomography (CT) revealed findings compatible with mediastinitis. He died of sepsis 12 d after the admission.

The management of acute bleeding episodes from ruptured esophageal varices consists of volume replacement, pharmacological, mechanical (balloon tamponade), and surgical modes of arresting hemorrhage. While balloon tamponade using SB tube is effective in achieving initial hemostasis, it has a significant complication rate. The most common complications of esophageal balloon therapy for varices include aspiration, esophageal perforation, and pressure necrosis of the mucosa[2]. The exact incidence of complications is difficult to determine, as it varies with the skill and experience of the surgical team, the duration of treatment, and the status of the patient. Aspiration of secretions is the most common complication of balloon tamponade, occurring in approximately 10%-20% of cases[3].

As described in past literature, cases with esophageal perforation can occur as a result of difficult SB tube insertion[4], retching and vomiting[5], and repeated endoscopic sclerotherapy[6]. In each of our cases, the SB tube was inserted without documented difficulties. Intragastric position was confirmed with auscultation. A radiographic localization of the SB tube before full inflation of the gastric balloon was ignored. The diagnosis of esophageal perforation in each case was confirmed by a follow-up chest radiograph taken after full inflation of the gastric balloon. Though uncommon, esophageal rupture due to SB tube misplacement carries a high incidence of mortality from hemothorax or septic mediastinitis, as demonstrated in our patients.

In conclusion, following insertion of the SB tube, confirmation of tube placement by auscultation alone may not be adequate. Routine chest radiographs should be obtained before and after full inflation of the gastric balloon to confirm correct tube position and to detect tube dislocation as soon as possible.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | McGrath RB. Inadvertent gastric balloon inflation within the chest in the management of esophageal varices. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:580-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vlavianos P, Gimson AE, Westaby D, Williams R. Balloon tamponade in variceal bleeding: use and misuse. BMJ. 1989;298:1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Avgerinos A, Armonis A. Balloon tamponade technique and efficacy in variceal haemorrhage. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994;207:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hamm DD, Papp JP. Rupture of esophagus during use of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Postgrad Med. 1974;56:199-200. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Zeid SS, Young Pc, Reeves Jt. Rupture of the esophagus after introduction of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Gastroenterology. 1959;36:128-131. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Crerar-Gilbert A. Oesophageal rupture in the course of conservative treatment of bleeding oesophageal varices. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:225-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |