Published online Oct 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5905

Revised: February 13, 2005

Accepted: February 18, 2005

Published online: October 7, 2005

AIM: To analyze the clinical features, management, and outcome of treatment of patients with primary intestinal and colonic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (PICL).

METHODS: A retrospective study was performed in 37 patients with early-stage PICL who were treated in our hospital from 1958 to 1998. Their clinical features, management, and outcome were assessed. Prognostic factors for survival were analyzed by univariate analysis using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and log-rank test.

RESULTS: Twenty-five patients presented with Ann Arbor stage I PICL and 12 with Ann Arbor stage II PICL. Thirty-five patients underwent surgery (including 31 with complete resection), 22 received postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both. Two patients with rectal tumors underwent biopsy and chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. The 5- and 10-year overall survival (OS) rates were 51.9% and 44.5%. The corresponding disease-free survival (DFS) rates were 42.4% and 37.7%. In univariate analysis, multiple-modality treatment was associated with a better DFS rate compared to single treatment (P = 0.001). While age, tumor size, tumor site, stage, histology, or extent of surgery were not associated with OS and DFS, use of adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved DFS (P = 0.031) for the 31 patients who underwent complete resection. Additional radiotherapy combined with chemo-therapy led to a longer survival than chemotherapy alone in six patients with gross residual disease after surgery or biopsy.

CONCLUSION: Combined surgery and chemotherapy is recommended for treatment of patients with PICL. Additional radiotherapy is needed to improve the outcome of patients who have gross residual disease after surgery.

- Citation: Wang SL, Liao ZX, Liu XF, Yu ZH, Gu DZ, Qian TN, Song YW, Jin J, Wang WH, Li YX. Primary early-stage intestinal and colonic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Clinical features, management, and outcome of 37 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(37): 5905-5909

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i37/5905.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5905

Primary intestinal and colonic Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (PICL) is an extra-nodal gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma, which is less common than gastric lymphoma. In fact, the clinical features and treatment of patients with the disease in these two locations are different. Patients with PICL generally have a lower survival rate than those with gastric lymphoma and the best management is yet to be developed[1]. The role of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy in patients with PICL has not been defined. This study was to evaluate the clinical features, management and outcome of patients with PICL.

During the period between 1958 and 1998, 37 patients with early-stage PICL were treated in our institution. Staging was based on physical examination, blood cell count, blood chemistry, chest X-ray or chest computed tomography (CT), ultrasonograms or CT of the abdomen. Some patients whose tumor was located in the colon or rectum underwent colonoscopy and biopsy or received an air-contrast barium enema. Bone marrow biopsy was performed for 22 patients. All diagnoses were confirmed by histology showing Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHLs). Immunophenotyping was performed in 34 patients, all showing B-cell origin. PICL was staged using the Ann Arbor classification system and graded according to the National Cancer Institute’sWorking Formulation.

Surgery included tumor plus partial intestine or colon resection and tumor resection only. The chemotherapy regimens consisted of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP); bleomycin, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (BACOP); or cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (COP). Treatment ranged from 1 to 9 courses (median, 5 courses). Radiotherapy was administered to the whole abdomen and the whole pelvis in 11 patients, to the whole pelvis or lower abdomen in 3 patients (1 patient had rectal, 1 had ascending colonic, and 1 had ileocecal lymphoma). No details were available for one patient. The median abdominal dose was 40 Gy (range, 26-45 Gy), and the median pelvic or lower abdominal dose was 40 Gy (range, 26-50.5 Gy). 60Co g, 6 MV X, or 8 MV X-rays were used to deliver irradiation. The dose per fraction varied from 1.5 to 2.0 Gy.

Follow-up evaluation included patient history, physical examination, blood cell count, blood chemistry analysis, reviews of chest X-ray films, and abdominal ultrasonograms, air-contrast barium enema, and/or endoscopic evaluation, CT of the abdomen. We obtained follow-up data from the hospital charts, reports from the local hospitals mailed to our hospital, forms filled in by patients and their local physicians, or telephone calls. OS was calculated from the date of treatment to death or to the date of last contact. DFS was calculated from the date of treatment to the date of disease relapse. Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the duration of survival, the difference in survival between groups was compared by log-rank test.

Patients including 27 males and 10 females ranged in age from 5 to 68 years (median, 42 years). The primary sites of tumor involvement were the ileocecal region in 20 patients, the ascending colon in 9, the ileum in 4, the rectum in 3, and the jejunum in 1. The median tumor size was 6 cm, ranging 1.8-22 cm. The most frequent symptom was abdominal pain (n = 26, 73%), for which five patients required emergency surgery, followed by abdominal mass (n = 17, 46%), intestinal bleeding (n = 8, 22%), and bowel obstruction (n = 2, 5%). According to the National Cancer Institute Working Formulation, PICL was classified in 24 patients as high-grade, low-grade in 7, and unknown in 6. Twenty-five patients had stage I PICL and 12 had stage II PICL based on the Ann Arbor staging system.

Thirty-five patients underwent surgery (Table 1). Thirteen patients who underwent a complete tumor resection had surgery alone, 22 patients received postoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (Table 1). Two patients with rectal tumors had biopsy during colonoscopy: one received chemotherapy alone and the other received chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

| Characteristics | n |

| Surgery result | |

| Complete resection | 31 |

| Gross residual disease | 4 |

| Post-surgical treatment | |

| Complete resection plus radiotherapy | 8 |

| Complete resection plus chemotherapy | 6 |

| Complete resection plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 4 |

| Incomplete resection plus chemotherapy | 2 |

| Incomplete resection plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 2 |

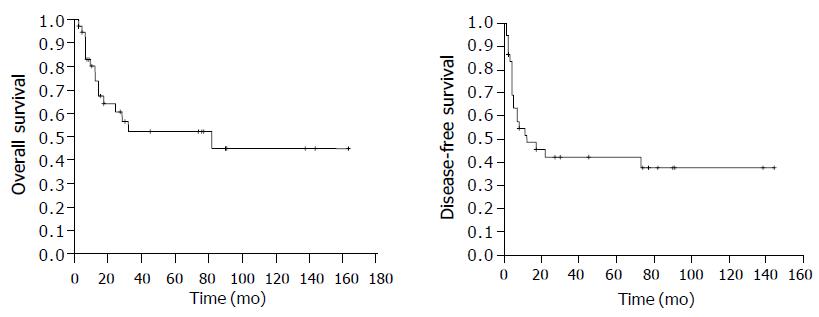

The median follow-up time was 17 mo for all patients and 45 mo for the surviving patients (range, 2-164 mo). The 5-year OS rate was 51.9%, the 10-year OS rate was 44.5%. The 5-year DFS rate was 42.4% and the 10-year DFS rate was 37.7% (Figure 1). Among the 21 patients who had relapse, 13 had loco-regional relapse, 4 had relapse at distant sites, and 4 had relapse at both loco-regional and distant sites. Among the 16 patients who received salvage therapy, 6 survived for 2, 3, 11, 71, 74, and 91 mo respectively, after disease relapse. Among the 14 patients who died, 12 died of lymphoma, 1 of cerebral arterial rupture, and 1 of hepatic failure due to hepatitis.

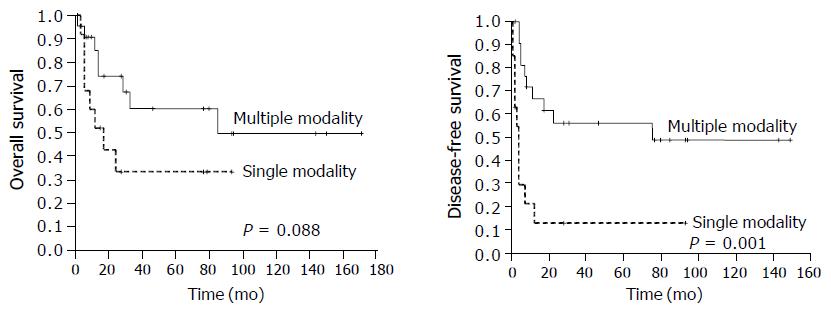

Univariate analysis showed that multiple modality treatment (surgery plus chemotherapy, surgery plus radiotherapy, surgery plus chemotherapy and radiotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy) achieved a higher DFS rate than single modality therapy (surgery and chemotherapy alone, P = 0.001, Figure 2), and a higher OS rate than single modality therapy but the difference was not significant (P = 0.088). Other factors including age, tumor size, histology, tumor site, stage, and extent of surgery had no significant correlation with survival probability (Table 2).

| Variable | Patients (n) | 5-year DFS % (relapses) | P | 5-year OS % (deaths) | P |

| Age | |||||

| ≤ 45 yr | 19 | 44.9 (11) | 0.719 | 65.9 (6) | 0. 270 |

| > 45 yr | 18 | 39.5 (10) | 36.8 (10) | ||

| Tumor size | |||||

| ≤ 6 cm | 17 | 52.3 (8) | 0.466 | 61.5 (6) | 0.092 |

| > 6 cm | 13 | 47.0 (7) | 55.9 (5) | ||

| Histology | |||||

| High grade | 24 | 42.2 (13) | 0.804 | 47.7 (11) | 0.888 |

| Low grade | 7 | 42.9 (4) | 66.7 (3) | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 40.0 (4) | 62.5 (2) | ||

| Tumor site | |||||

| Ileocecal region | 20 | 40.0 (12) | 0.742 | 57.6 (8) | 0.479 |

| Colon and rectum | 12 | 40.7 (7) | 37.1 (7) | ||

| Intestine | 5 | 60.0 (2) | 66.7 (1) | ||

| Stage | |||||

| I | 25 | 37.9 (16) | 0.2 | 48.0 (12) | 0.35 |

| II | 12 | 49.9 (5) | 59.3 (4) | ||

| Surgery | |||||

| Complete resection | 31 | 41.4 (18) | 0.382 | 53.4 (13) | 0.948 |

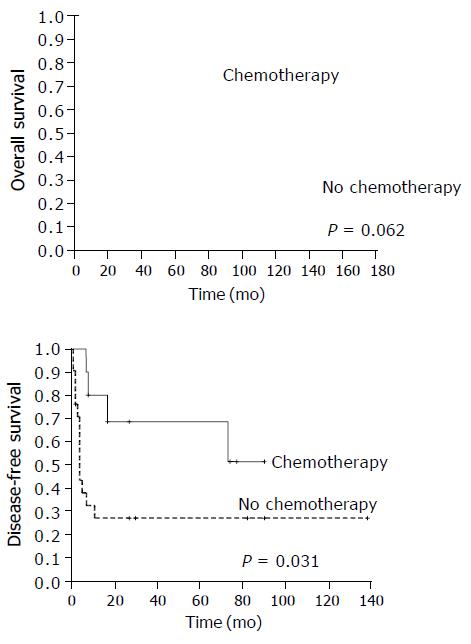

In respect to the 31 patients who underwent complete tumor resection, there was a significant difference in DFS rates between patients who received chemotherapy and those who did not. The 5-year DFS rates were 68.6% and 27.2% respectively, being in favor of the chemotherapy group (P = 0.031). The 5-year OS rate was 70.0% for patients treated with chemotherapy and was 45.3% for patients without chemotherapy (P = 0.062, Figure 3). Postoperative radiotherapy tended to improve DFS but not OS. The 5-year DFS rates were 54.6% and 34.0% (P = 0.087), while the 5-year OS rates were 54.1% and 51.4% for patients with and without radiotherapy, respectively (P = 0.831).

Among the four patients with gross residual tumors after surgery and the two patients who underwent biopsy only, three patients received combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy and three patients received chemotherapy alone. The three patients who received chemotherapy alone had relapse 5, 12, and 22 mo after treatment and died of lymphoma 12, 17, and 28 mo after treatment. However, the three patients who received additional radiotherapy besides chemotherapy had no evidence of relapse 45, 91, and 144 mo after treatment.

This retrospective analysis of 37 patients with PICL showed the clinical features of PICL. It was reported that primary intestinal lymphoma accounts for 18.9-62.2% of all primary GI NHLs, and the most frequent sites of origin are the small bowel or ileocecal region, followed by the colon, rectum, and duodenum[2,3]. Most are classified as high-grade NHL. The main symptoms are pain, occult loss of blood or macroscopic bleeding, palpable abdominal mass, bowel obstruction, and perforation. These symptoms occur more frequently in patients with intestinal NHL than in those with gastric NHL, and emergency surgery is necessary for some cases[4,5]. Prognostic factors include advanced disease stage[6], intestinal perforation[7,8], high grade histology[9], and T-cell lymphoma[10,11], which are associated with a lower survival rate. In our study, no patients had T-cell lymphoma. Due to the small number of patients, we did not detect any influence of stage, histological subtype, or sites of origin on the survival time.

Surgery plays an important role in the treatment of PICL. Emergency surgery is required in some cases to reduce the risk of complications and to improve the symptoms such as obstruction or bleeding. Most importantly, surgery can improve the survival of patients with PICL. It was reported that surgical resection is the only statistically significant prognostic variable for patients with intestinal lymphoma[12]. The favorable effects of debulking surgery (partial or complete resection) on OS and DFS were also emphasized[13]. It was reported that the 5-year survival rates were 46% and 0% for patients after radical resection and non-radical resection, respectively[14]. Jinnai et al[15] found that the 5-year survival rate was 44.2% for patients with malignant lymphoma after curative resection, while none survived 5 years after non-curative resection. In our study, surgery was the primary treatment for almost all patients except for two patients with rectal tumor, and the 5-year OS rate was 51.9%. The extent of surgery did not affect survival, because all patients after incomplete surgery received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or both, suggesting that multiple-modality treatment confer a superior survival advantage over surgery alone or chemotherapy alone.

Chemotherapy significantly improved the DFS rate of patients after complete surgical resection in our study, which is consistent with the reported findings[16]. The efficacy of surgery-chemotherapy combination has been confirmed by other studies[17-19].

In conclusion, surgery is the primary diagnostic and treatment modality for PICL, chemotherapy is necessary for improving the survival of PICL patients, and radiotherapy affords additional benefits to patients with gross residual disease after surgery.

The authors thank Pamela Allen, PhD (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA) for helping us to analyze the data, and James D Cox, MD (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA) for revising the manuscript.

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Bierman PJ. Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:421-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gurney KA, Cartwright RA, Gilman EA. Descriptive epidemiology of gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1929-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3861-3873. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Azab MB, Henry-Amar M, Rougier P, Bognel C, Theodore C, Carde P, Lasser P, Cosset JM, Caillou B, Droz JP. Prognostic factors in primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A multivariate analysis, report of 106 cases, and review of the literature. Cancer. 1989;64:1208-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liang R, Todd D, Chan TK, Chiu E, Lie A, Kwong YL, Choy D, Ho FC. Prognostic factors for primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 1995;13:153-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morton JE, Leyland MJ, Vaughan Hudson G, Vaughan Hudson B, Anderson L, Bennett MH, MacLennan KA. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a review of 175 British National Lymphoma Investigation cases. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:776-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Amer MH, el-Akkad S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:846-858. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Domizio P, Owen RA, Shepherd NA, Talbot IC, Norton AJ. Primary lymphoma of the small intestine. A clinicopathological study of 119 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:429-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Takeshita M, Kurahara K, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. A clinicopathologic study of primary small intestine lymphoma: prognostic significance of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-derived lymphoma. Cancer. 2000;88:286-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, Dederke B, Foss HD, Stein H, Thiel E, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on Intestinal non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2740-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kohno S, Ohshima K, Yoneda S, Kodama T, Shirakusa T, Kikuchi M. Clinicopathological analysis of 143 primary malignant lymphomas in the small and large intestines based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology. 2003;43:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gobbi PG, Ghirardelli ML, Cavalli C, Baldini L, Broglia C, Clò V, Bertè R, Ilariucci F, Carotenuto M, Piccinini L. The role of surgery in the treatment of gastrointestinal lymphomas other than low-grade MALT lymphomas. Haematologica. 2000;85:372-380. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ibrahim EM, Ezzat AA, El-Weshi AN, Martin JM, Khafaga YM, Al Rabih W, Ajarim DS, Al-Foudeh MO, Zucca E. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: clinical features, management, and prognosis of 66 patients. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P. Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1628-1638. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Jinnai D, Iwasa Z, Watanuki T. Malignant lymphoma of the large intestine--operative results in Japan. Jpn J Surg. 1983;13:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | d'Amore F, Brincker H, Grønbaek K, Thorling K, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Andersen E, Pedersen NT, Mortensen LS. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1673-1684. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Pagliani G, Bendandi M, Gherlinzoni F, Merla E, Salvucci M, Tura S. Primary intestinal lymphoma: clinical and therapeutic features of 32 patients. Haematologica. 1997;82:305-308. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Pandey M, Kothari KC, Wadhwa MK, Patel HP, Patel SM, Patel DD. Primary malignant large bowel lymphoma. Am Surg. 2002;68:121-126. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Doolabh N, Anthony T, Simmang C, Bieligk S, Lee E, Huber P, Hughes R, Turnage R. Primary colonic lymphoma. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |