Published online Aug 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i32.5068

Revised: April 5, 2005

Accepted: April 9, 2005

Published online: August 28, 2005

Among the various congenital anomalies of the biliary system, an ectopic opening of the common bile duct (CBD) in the duodenal bulb is extremely rare. ERCP is essential for diagnosing the anomaly. A 55-year-old male was admitted to hospital for severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain, followed by fever, chills, elevated body temperature and mild icterus. The diagnosis of ectopic opening of CBD in the duodenal bulb was established on endoscopic ultraso-nography (EUS), which clearly demonstrated dilated CBD, with multiple stones and air in the lumen, draining into the bulb. A normal pancreatic duct, which did not drain into the bulb, was also observed. This finding was confirmed on ERCP and surgery. As far as we know, this is the first case of this anomaly diagnosed by EUS. Ectopic opening of the CBD in the duodenal bulb is not an incidental finding, but a pathologic condition which can be associated with clinical entities such as recurrent or intractable duodenal ulcer, recurrent biliary pain, choledocholithiasis or acute cholangitis. Endoscopic ultrasonography features allow preoperative diagnosis of this anomaly and can replace ERCP as a first diagnostic tool in such clinical circumstances. Embryology of the anomalies of the extrahepatic biliary tree has been also reviewed.

- Citation: Krstic M, Stimec B, Krstic R, Ugljesic M, Knezevic S, Jovanovic I. EUS diagnosis of ectopic opening of the common bile duct in the duodenal bulb: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(32): 5068-5071

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i32/5068.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i32.5068

Among the various congenital anomalies of the biliary system, an ectopic opening of the common bile duct (CBD) in the duodenal bulb is extremely rare. Until recently, there were only a few sporadic case reports of this anomaly in the literature worldwide[1-3]. In 2003, Lee et al[4] presented the largest study consisting of 18 Patients with this anomaly. In that study, as well as in case reports published elsewhere, the diagnosis of an ectopic opening of the CBD in the duodenal bulb was established on ERCP when: (1) an orifice was observed in the bulb by duodenoscopy or upper endoscopy, and the bile duct and/or the pancreatic duct were directly visualized radiographically, when contrast was injected via this opening; (2) there was direct drainage of the CBD into the duodenal bulb without evidence of any other drainage into the duodenum on cholangiography; and (3) there was no evidence of a papilla-like structure in the second or third portion on duodenoscopic examination[1-4]. However, ERCP is an invasive endoscopic procedure which is associated with significantly greater morbidity and mortality, when compared with either upper endoscopy or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)[5]. Septic complications of ERCP can be life-threatening[6]. Mortality rates for post-ERCP cholangitis vary from 10 to 16%[7]. On the other hand, diagnostic EUS is a non-invasive endoscopic procedure with negligible rate of complications. We present, for the first time, a patient with ectopic opening of the CBD in duodenal bulb, diagnosed by EUS.

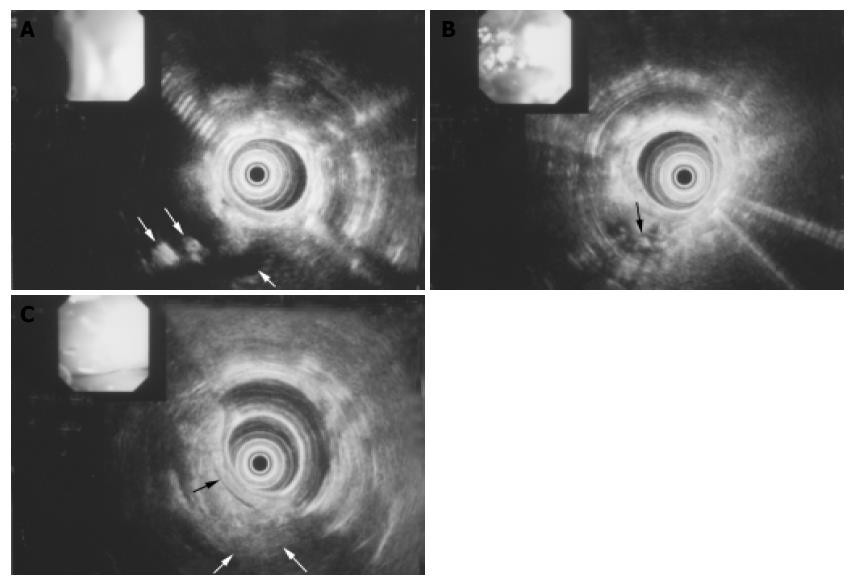

A 55-year-old male presented at the University Clinic for Gastroenterology on March 27, 2002, with severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain, followed by fever, chills, elevated body temperature (39.5 °C) and mild icterus. His history revealed two identical attacks in the previous 4 mo, which subsided with parenteral antibiotics at a local hospital. His body weight loss in the previous 6 mo was more than 10 kg. In 1998, he was operated on due to malignant melanoma and had a history of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus for the previous 4 years. On admission, physical examination revealed only mild tenderness in the upper abdomen followed by obscure jaundice. Routine biochemistry revealed cholestatic pattern: elevated alkaline phosphatase 149 U/L (n<70 U/L), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 404 U/L (n<35 U/L), conjugated bilirubin 35 µmol/L (n<11 μmol/L) and ALT 88 U/L (n<23 U/L). Abdominal ultrasonography performed at our hospital disclosed gall bladder with few small gallstones, dilatation of the common bile duct of more than 20 mm, with suspicious stones in the lumen, and a pseudotumor in the projection of the duodenal bulb. The computed tomography finding was unremarkable revealing only discreet intrahepatic biliary dilatation in left liver lobe. Endoscopic examination of the duodenum disclosed bulbar deformity without ulcers and erosions, as well as a slit-like opening on the posterior bulbar wall from which bile flowed intermittently, especially when suction was applied with the endoscope (Figure 1). At that particular moment, our idea was that a spontaneous fistula, secondary to choledocholithiasis or ulcer disease had occurred in this patient. Endoscopic ultrasonography examination of the upper GI tract and biliary system (using radial 7.5/12 MHz switchable probe-Olympus device) was carried on. EUS exploration from the duodenal bulb with the 7.5 MHz radial probe clearly demonstrated dilated common bile duct with multiple stones and air in the lumen, draining in the duodenal bulb (Figures 2A and B). There were no EUS signs of fistula. The mild lobulation and inhomogeneity of pancreatic parenchyma was also documented, since the main pancreatic duct appeared non-dilated and unchanged and was not draining into the duodenal bulb (Figure 2C).

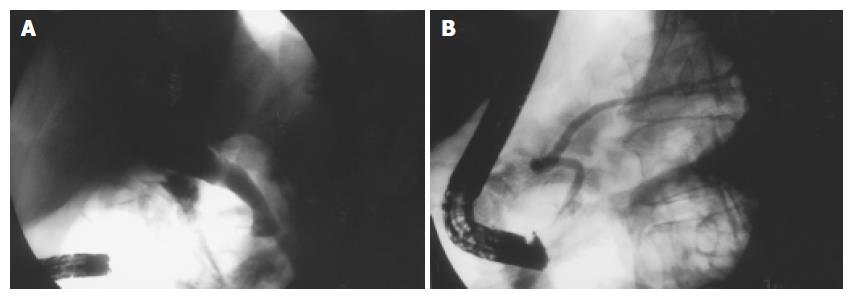

The final diagnosis of an ectopic opening of the CBD in the duodenal bulb was confirmed on ERCP, where markedly dilated biliary tree with stones was directly visualized radiographically on injection of contrast via the orifice observed previously in the bulb. Technically, it was especially demanding to cannulate the opening in the duodenal bulb blindly with duodenoscope placed horizontally in the stomach body (Figure 3A). At the end of this procedure, cannulation of the major duodenal papilla, which appeared regularly in the descending duodenum, disclosed the unchanged main pancreatic duct, making a loop in the head of pancreas (Figure 3B).

The patient underwent surgery including open cholecy-stectomy, bile duct exploration with subsequent extraction of biliary stones, and choledochoenterostomy (Figure 4). On the 7th d after the operation, the patient was discharged from the hospital. Two years after the operation, he has been doing well and denied any symptoms.

The embryonic development of the liver and biliary tree begins late in the 3rd wk of intrauterine development, when a small hepatic diverticulum arises from the thickened area of endoderm (epithelium), at the junction of the foregut and the midgut[8]. The cells of hepatic diverticulum penetrate the mesenchyma of the ventral mesogastrium, dividing into a ventral and a dorsal bud. The ventral bud (pars cystica) stays close to the free edge of the mesogastrium, and, after developing a lumen, forms the primitive gall bladder. The dorsal bud (pars hepatica) divides in turn to the left and right liver lobe primordia. As the liver and biliary tree develop inseparably, these primordia multiply to form an epithelial spongework or cords which come in close relation to vitelline and umbilical veins. The stem of the hepatic primordium becomes the bile duct, its connection to the ventral bud forms the cystic duct, and the divisions of the dorsal bud become left and right hepatic ducts. Initially, the gall bladder is a hollow organ, but, as a result of proliferation of its epithelial lining, it becomes temporarily solid. The definite lumen develops by recanalization of the epithelium. The intra- and extrahepatic ducts also go through a solid and recanalization stage in their development. If their lumen fails to reopen, the ducts will appear as narrow, fibrous cords. Occasionally, such an atresia is limited to a small portion of the bile duct only. Another important feature of the bile duct development is rotation of the primitive duodenum 90 on its longer axis, which brings the bile duct dorsal to the upper limb of duodenum.

The development of duodenum, pancreas, and bile ducts has been wittily described as embryological “traffic jam”[9]. In a case report of a complete absence of bile and pancreatic ducts in a newborn[10], it has been postulated that there may be a genetic factor related to defects in the liver and pancreas. Like those genes themselves, their products are largely unknown, as are the interactions of the few products that have been identified[8].

Variations in the extrahepatic duct topography, which extend from the complete absence of the CBD[11] anomalous opening of the biliary tree[12] through accessory hepatic ducts to duplications of the gall bladder or the bile duct, are thought to arise from the difference in extension and projection of the analage derived from the caudal hepatic bud.

The description of the development of liver, pancreas and connected duct systems provides no evidence that two extrahepatic ducts with separate openings into the gastrointestinal tract are stages in normal organogenesis[13], so that the development of double common bile duct can be ascribed to disturbances in recanalization of the hepatic primordium. The accessory bile duct can open into various parts of the digestive tube-stomach[14], all four portions of the duodenum, pancreatic duct, or can be only presented by a septum in the common bile duct[15].

According to the above-mentioned criteria for diagnosing ectopic opening of CBD in the duodenal bulb[4], in such cases there should be no evidence of a papilla-like structure in the lower duodenum. This is in contradiction to a previous report[16], which permits the possibility of the pancreatic duct opening elsewhere in the duodenum, apart from the ectopic CBD. In our case, we clearly demonstrated an ectopic opening of CBD in the duodenal bulb, and, apart from it, the existence of a normal pancreatic duct opening through the papilla in the descending duodenum. Therefore, we hypothesize that the primary embryological event was the duplication of the common bile duct (double CBD). One of those ducts had an anomalous opening in the duodenal bulb, while the other took a normal course to join the pancreatic duct. The latter duct probably underwent atresia, which left the whole biliary drainage through the ectopically positioned duct. This is in accordance with the fact, that the pancreatic duct has been visualized in only 1/8 and 7/18 cases in the previous studies on ectopic opening of CBD into the duodenal bulb[16,4]. Therefore, we suggest that the 3rd criterion concerning the papilla-like structure in the descending duodenum should be discarded.

An ectopic opening of the common bile duct in the duodenal bulb is extremely rare. The percentage of asymptomatic individuals is unknown, since there was no consistent autopsy study[4]. Until recently there were only a few sporadic case reports of symptomatic anomaly[1-3]. However, true incidence could be much higher than presently appreciated, as Lee et al[4] stressed recently. They concluded that ectopic opening of the CBD in the duodenal bulb is not an incidental finding, but a pathologic condition which can be associated with clinical entities such as recurrent or intractable duodenal ulcer, recurrent biliary pain, choledocholithiasis or acute cholangitis. Our patient had two episodes of acute cholangitis in regional hospitals before establishing correct diagnosis. The same scenario took place in other studies, whereas anomaly was not diagnosed in any patient before referral to tertiary institutions, where the patients were evaluated[16].

The diagnostic tools for such entities ranged from plain upper GI barium X-ray[17], operative cholangiography[1] to CT[16], but ERCP is the “golden standard”. However, ERCP is an invasive endoscopic procedure, which is associated with a variety of possible complications[18]. Some of them, like sepsis can be life-threatening[6]. Mortality rate for post-ERCP cholangitis is very high, reaches even 16%[7]. On the other hand, diagnostic EUS is a non-invasive endoscopic procedure with negligible rate of complications.

For the first time, we presented clear EUS features of this anomaly, which undoubtedly excluded other possibilities in differential diagnosis: fistula secondary to ulcer disease or choledocholithiasis or spontaneous biliodigestive fistula. Endoscopic ultrasonography features allow preoperative diagnosis of this anomaly and can replace ERCP as a first diagnostic tool in such clinical circumstances.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Lindner HH, Peña VA, Ruggeri RA. A clinical and anatomical study of anomalous terminations of the common bile duct into the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1976;184:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kubota T, Fujioka T, Honda S, Suetsuna J, Matsunaga K, Terao H, Nasu M. The papilla of Vater emptying into the duodenal bulb. Report of two cases. Jpn J Med. 1988;27:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Doty J, Hassall E, Fonkalsrud EW. Anomalous drainage of the common bile duct into the fourth portion of the duodenum. Clinical sequelae. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1077-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Kim KP, Kim HJ, Bae JS, Kim HJ, Seo DW, Ha HK, Kim JS. Ectopic opening of the common bile duct in the duodenal bulb: clinical implications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:679-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 835] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1687] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Knisely AS. Biliary tract malformations. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122A:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Heij HA, Niessen GJ. Annular pancreas associated with congenital absence of the gallbladder. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nakamura K, Mitsubuchi H, Miyayama H, Yatsunami K, Ishimatsu J, Yamamoto T, Endo F. Complete absence of bile and pancreatic ducts in a newborn: a new entity of congenital anomaly in hepato-pancreatic development. J Hum Genet. 2003;48:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olsha O, Steiner A, Rivkin LA, Sheinfeld A. Congenital absence of the anatomic common bile duct. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1987;153:387-390. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rajnakova A, Tan WT, Goh PM. Double papilla of Vater. A rare anatomic anomaly observed in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:345-348. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Teilum D. Double common bile duct. Case report and review. Endoscopy. 1986;18:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kanematsu M, Imaeda T, Seki M, Goto H, Doi H, Shimokawa K. Accessory bile duct draining into the stomach: case report and review. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamashita K, Oka Y, Urakami A, Iwamoto S, Tsunoda T, Eto T. Double common bile duct: a case report and a review of the Japanese literature. Surgery. 2002;131:676-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee HJ, Ha HK, Kim MH, Jeong YK, Kim PN, Lee MG, Kim JS, Suh DJ, Lee SG, Min YI. ERCP and CT findings of ectopic drainage of the common bile duct into the duodenal bulb. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:517-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holz K. Atypical orifice of the common bile duct during localization of the Vater papilla on the rear wall of the duodenal bulb. Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed. 1970;112:409-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kohut M, Nowak A, Nowakowska-Duiawa E, Marek T. Presence and density of common bile duct microlithiasis in acute biliary pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:558-561. [PubMed] |